“Hoolboom’s most recent film transcribes the history of the body as a moving image/object. From Chaplin’s portrayal of the worker as caught in the wheel of industry, to the rapid-fire representation of skin over skin, this is a body legitimated by light.” Pleasure Dome

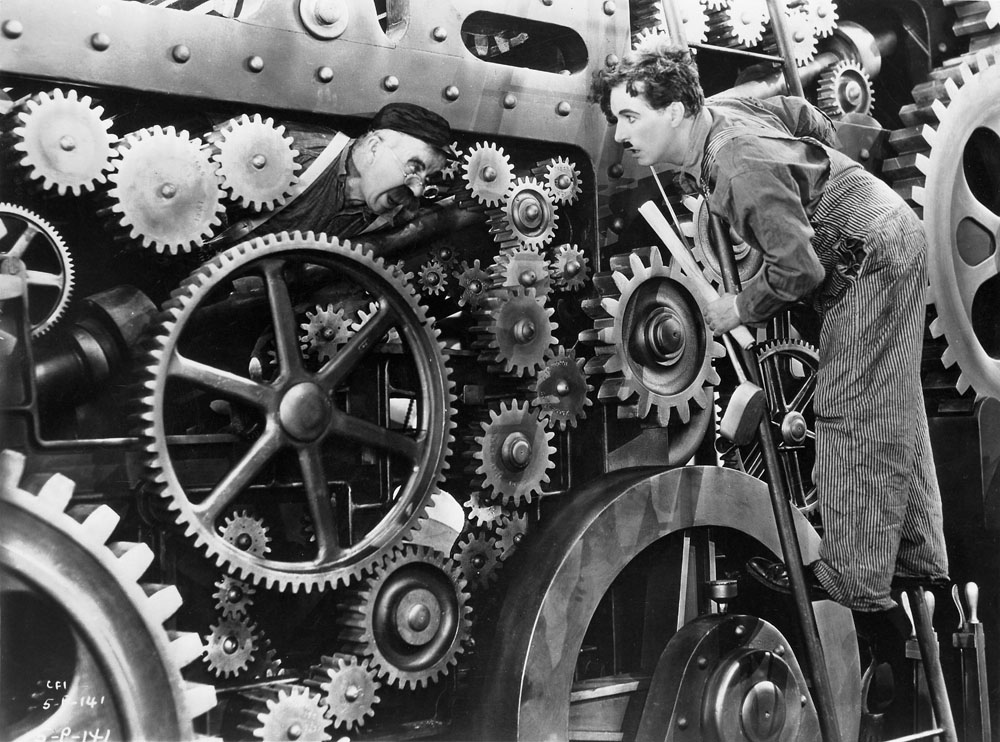

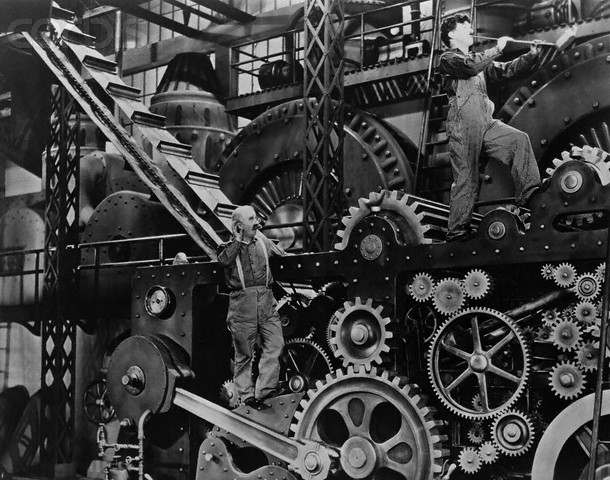

“Mike Hoolboom is the most energetic figure of the recent generation of Canadian filmmakers. His film, Modern Times, is like a little essay on what happens to the human body when it meets a movie camera. Modern Times synthesizes, for the first time, the two concerns which have driven most of Hoolboom’s previous work: questions of the cinema (the body of film history), and questions of the maker (the body of the maker). Modern Times begins and ends in darkness” just like any film screening. At the beginning there is only a voice. A child listens to a war veteran’s story. The veteran tells of how he shot people not with a gun, but with a camera. At the end of the film the camera moves towards a drawer which it enters. The drawer closes. The drawer is a closed little black box, like the camera” a box without light. In appropriated images from an old Charlie Chaplin movie, we see Chaplin caught within the mechanism of a machine. He is drawn along a path similar to that of a movie camera, implying that the camera is not neutral, that we end up living inside the machine and seeing the world as the machine sees it.” Martin Rumsby

“Starting from his meeting with a war reporter who used to shoot news footage with an old Bolex camera, Hoolboom dives into this other world, the world he imagines at the other end of the cinematographic process: a world of its own, in which the past can be reinvented. Holding on to the revealing quality of the image, his guiding principle “come out to show them” is playfully given shape in this dazzling collage of body parts and sound excerpts, seducing us by a rhythm which transforms a peaceful adagio into a house music experience.” Miryan van Lier, Visions du Reel, 1997

“Four minute long movie whose title is a paraphrase of Chaplin’s famous film describes the history of the body as a moving object. Movie’s abrupt cuts remind of comical Chaplin as a worker caught by a machine and it all ends in abstract light patterns. Are these lines still Chaplin? And the darkness is he, too?” Petr Kubica, Jihlava Festival

“Industry has rhythm. So does the hand-cranking of an old Bolex, and so too (in spades) does this punchy mediation on a body crushed by the wheels of industry.” Geoff Pevere, Images Festival

Modern Times is a film essay on the camera, taking the shape of its subject as its own. It opens and closes in darkness, forming a dark box which contain the images within. Its opening passage of dark is related in voice-over: “He came to stay after the war. He was working as a reporter. He used to take pictures so when it was over he made pictures for the news. He used an old Bolex you had to crank by hand, and after he got it all wound up he would look into it for a long time. I thought his camera was the door to another world, that the fantastic things we saw at the movies all came from that dark place, that he was inventing a past we couldn’t remember anymore. I asked if I could take a look.” The narrator’s “look” gives out on the film’s first image, shot in the day’s last light, people passing in silhouette in a narrow curtain of yellow rays while the dogs of war howl unseen. The title appears, Modern Times, and then the film’s central image reports. A hand winding up a spring-loaded movie camera. The film’s primal scene. This circling hand is intercepted by pictures borrowed from Charlie Chaplin’s proletarian tear jerker Modern Times. Charlie is tightening screws on an assembly line which moves quicker than he’s able” and in a frantic effort to keep up, he chases after the unfinished parts and is swept into the bowels of the machine” his body wound through a transport of belts and wheels which bear an uncanny resemblance to the film path of a projector or camera.

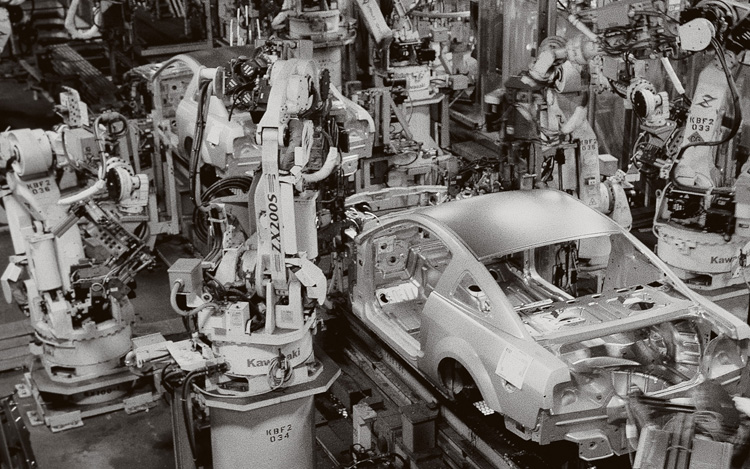

Charlie’s industrial accident joins the film’s themes of assembly lines and movie cameras. I was thinking about auto assembly plants” trying to crawl into the head of someone who would have imagined such a thing. I imagine Henry Ford ten star drunk, on the ski slopes trying to impress a woman that looks like his daughter” so he charges off the lift and fairly plummets down the slopes until he hits this small tree and there is only pain and horror and blood as he looks over and sees his right arm dangling off the tree. He passes out. The next morning he wakes up and sees that the doctors have sewn his arm back on and he has a moment of terrible revelation, a moment that would come to haunt generations to come. His body is made of parts. And these parts can be removed and replaced. This is how he comes to his idea of the assembly line. He stops imagining a finished car, the car you get in and drive away. Nope, everywhere Henry looks there are only parts stitched together. He took his car and smashed it into bits, granting each bit a name and a worker. You are responsible for the bumper. You are responsible for the drive shaft. All of these parts taken together would make a car. But Henry Ford was never interested in building cars. He wanted to change the way we lived. So he made a picture with four wheels and a steering column. An image of the new human being. Who was similarly broken and fragmented; whose bodily mirror would soon be seen smoking through the streets of every town in America. As I sat thinking about Henry, I wondered that film was also constructed on a line “like the assembly line in one of Henry’s plants” and that it was similarly transported by a universe of machines.

There is no motion in a motion picture. Film is comprised of individual photographs, chained together and cranked quickly through a machine producing the illusion of movement. These isolated frames also show a body of parts, a body as imagined by the machine, a Frankenstein body whose founding gesture was an atomization of the body a ripping apart and rending, an immolation. These fragments are joined in the lamp of the projector, chained together to further an illusory unity. But the idea or ideology which supports this unity is the fragmenting action of the motion picture camera. It “sees” its subject as a compact of parts, an accretion of divisions, it rips the body apart beneath a surgeon’s stare. And this is how we’ve come to understand our own bodies. As parts and moments. As teeth to be brushed, cheeks to be powdered, asses to be wiped and nails to be clipped and lips to be rouged. As an accumulation of products. An effect of the machine. I think this is what McLuhan meant when he said that the medium was the message. We don’t just use machines. We assume their attitudes.

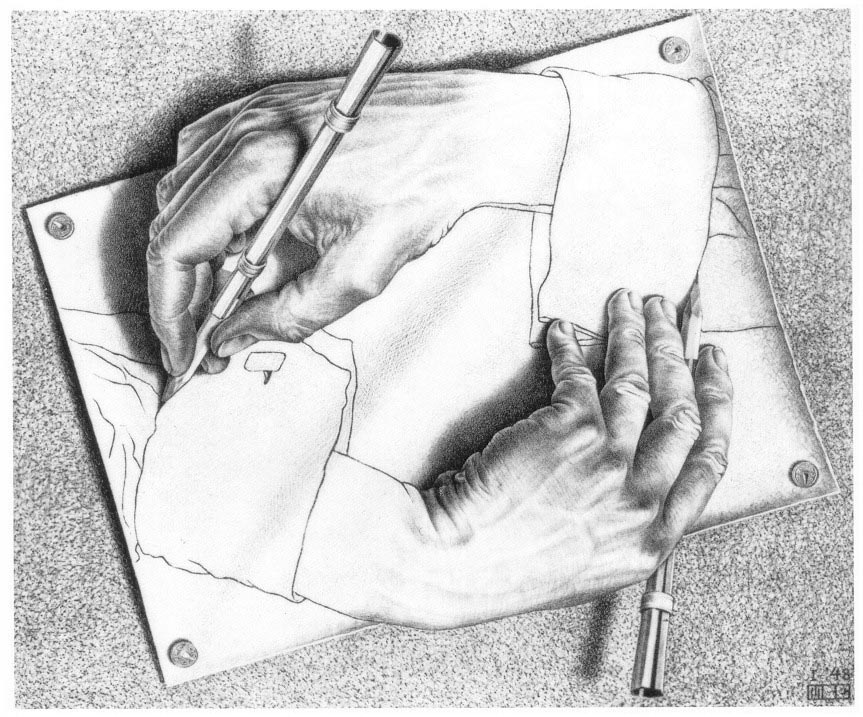

This shared secret, this compact of machines drawn between Ford and film, is shown at the moment when Chaplin is sucked into the machines of the assembly line” which as a film director he had designed to resemble the guts of a film camera. For a brief time he is wound round the machine path, moving inside it like any other of its products. But instead of seeing Chaplin emerge, we see a naked man who appears as the ‘effect’ of the machine. Photographed a frame at a time against a black backdrop, his flickering, shuddering countenance struggles to stand as the camera renders him as a Cubist study, moments of flesh erupting, a broken body of parts made to stand. He is being reborn as a machine. Delivered to it involuntarily, out of a sense of duty, of workmanlike pride, he enters the machine in order that the machine might have its way with him, his shaking flesh a blank on which the machine’s wishes are written. On the soundtrack a voice insistently repeats, “Come out, come out, come out” line workers calling for a comrade lost in the machine. Finally he passes into black, the voice still sounding. The camera sweeps over a T-shirt which shows an Escher painting of two hands (each drawing the other: an image of reflexivity , of modernity , ‘modern’ times) before it lurches towards a drawer. A hand opens it and the camera plunges inside. The drawer closes and the film is over. In the darkness of this drawer. This camera.