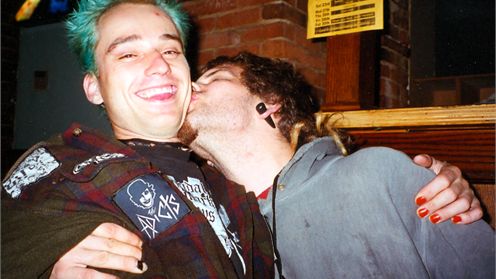

Mark Karbusicky (1972-2007)

Mark and I spent many hours together in the dark, looking in the same direction, looking at pictures. For the last six years he has been coming with me to Charles Street Video and editing my movies, which are known most of all for their editing, which is Mark’s contribution. I think this role of editor is very typical for Mark, which allows someone else to realize their hope, while he is very quietly in the background. Working. He was always working. An editor brings together moments which seem impossible, or part of very different worlds. An editor has a sense of how these different moments might fit together, belong together after all. An editor has an eye for what is held in common, qualities that are shared between people or events, which seem far apart. The editor is the first one who can recognize this, once they are joined oh of course, it couldn’t be any other way, but before Mark puts it together, it’s so difficult to imagine. It’s a way of working, but also a way of living in the world, of seeing these connections, of living these connections.

For the first few years Mark would always arrive with a large knapsack, which would contain either two cans of Jolt Cola, or a single large bottle of Jolt Cola. Long sessions meant three cans. He drank every one as if it was the first.

There’s one other person I know who has this talent that Mark has for relentless optimism. It is so consistent that I realized quickly that this is something he’s worked on, the way others would work at making a perfect cup of coffee or working out a blues lick on the guitar. Almost every day I saw him Mark would offer some cheerful recipe, he applied it the way you applied a bandage, and he did it so often and so well that it gave me a hint of a darkness that was all his own, it was a darkness that required this tremendous diligence, this watchfulness, and the fact that he was able to do it with such lightness, the fact that he was able to turn it for so long into something positive, and affirming, I really marveled at it.

He was so large and capable, it just seemed like he knew how to do everything, and if there was a problem it was only a question of time before Mark, who so very rarely exhibited impatience or frustration, would offer another way of looking at it or approaching it, and he would cheerily tell me not to worry, he would be able to fix it, and he always did. Mark was always busy fixing things, and smoothing out difficulties.

It wasn’t until I saw Let’s Get Lost by Bruce Weber, that I could look into the wasted face of Chet Baker, and feel the pain that lay underneath all those sweet beautiful songs, the pain that made those songs possible.

The last time I saw Mark was in my apartment, sitting in the chair where I spend most of my life in front of the computer. We had finished this very very long journey of a film, and he had always been urging me not to work at the co-op, but to work at home, alone, by myself, the way he did it, even though it meant that I wouldn’t be hiring him for my projects anymore. For all those of you who knew him, I think you will recognize this gesture right away. There was never any thought on his part that he might be losing something, so he came to my place to give me his editing software, and he put it on my computer in that typical very thorough very careful Mark way. He insisted that we had to boot up the program and use the program, and then close it and then start it again, so that we could both be sure that it would absolutely work. He has been a model of kindness for me these many years, a kindness, it seems that he was able to extend more easily to others than to himself. I miss him very much.

May 2, 2007

Mark

His feet never seemed to quite hit the ground when he entered the room, blown in on some passing whim. He would greet me with a wave that came from the end of his scarf, and a “hiiii” that drawled the vowel so long we could both land on it. His name, which I glibly mispronounced for years without his ever once correcting it, was Mark Karbusicky. Mark was an editor and through six winters we sat together in the dark, sieving pictures through a computer, his large capable hands interfacing with the machine. I wasn’t able to see then the way his lightness was also a way of erasing every step, as if he were walking backwards through the snow with a broom, leaving no traces. Now you see me, now you don’t.

We made a portrait of my friend Tom, and then a collection of shorts which signed off with an extravagantly stuttering Porky Pig announcing, “Th-th-that’s all, folks.” Mark had a thing for these farm animals; like me, he was born in the year Chinese folks mark with a pig. And I can’t help thinking about the old woman over the bun shop who reads foreheads and warned me that every time the pig year rolled in—one in twelve—it would be time to face the music. To face what couldn’t be faced.

Last year—2007—belonged to the pig, and despite all reasonable warnings I came to the cinema one April night with no sense of warning. I think my whole life happens inside the movie theatre, every love and hope and failed dream lives and dies there. After settling into the frayed velvet seats, my friend Aleesa leaned close and said she had something to share when the curtain closed. Sure, why not. When the film was over she told me that Mark had hung himself with a dog leash.

He died in the year of the pig, aged 35. In the following months I was fortunate to meet with some of his friends and family, and in these encounters he would flicker alive in our mouths and then cruelly disappear. New informations surfaced, old ones passed away. Andy, his best friend from public school, had his arm tattooed with Mark’s birth and death dates on it. Mirha told me that Mark had become a spider, and the next day Kristyn said the balcony plant she’d potted in his honour hosted the largest spider she’d ever seen.

There had been no previous attempts, he left no note, there was no obvious reason why. Many were certain that there was a story to be told, that we had been granted only the last page. So where was the rest? But the many hours Mark and I had spent together mostly eluded squeezing pictures into story containers; we had both seen how darkness can spread slowly over a picture, making it impossible to see even when it was right there in front of us. News from the Gaza Strip, from Ho Chi Minh City, the streets of Sarajevo. There are entire cities which are buried in layers of invisible pictures. Mark and I kept busy working with small pictures, bringing them back into our computer archive where they could be endlessly re-edited and keep our own secrets company. Sometimes we succeeded too well. In all those years, how many things we never told each other, we never told ourselves.

He was a large man with a crooked beak of a nose and soft brown eyes that were better met when the light was low, they were so admitting they hurt to look at sometimes. The way he held himself shrank him in stature, even when he was a hot breath away showing me, again and again, how to make the impossible work, his touch was so effortlessly light that it seemed like I was practically alone, figuring it all out by myself. It was an old magician’s trick he practiced, the fine art of disappearance.

As long as I’d known Mark he was always telling me, “No problem.” One leg kicked up behind him, his arm bent into a backwards wave, head raised up in the air. There were no problems which belonged to others that he wasn’t busy patching, mending, attaching himself to. Which made us wonder how someone who had spent his life in service should have left so little for himself. He was busy feeding feral cat colonies around the city. He organized rallies against animal testing, provided years of research and technical support for a weekly animal-rights radio program, worked always with the poor and disadvantaged. And he had been shooting a movie.

It was about pigs, of course. He had made his way over to the Tecumseth Street slaughterhouse, in Toronto, drilled holes into the metal siding and built some kind of periscope arrangement so he could mirror pictures into his video camera. He was obliged to make these arrangements because, like all slaughter houses, this is a strictly no-camera zone—and for good reason. A cutting room floor awash with blood and freshly cut corpses is not the image that a meat-eating nation wants to promote. Animals are routinely skinned and gutted while still alive owing to the speed of the operation. And behind the camera black-out there are other problems. Injury compensation remains low, supervisors are given bonuses for minimizing recorded injuries and high production.

When Mark’s movie was finished I expected that we would sit down over a tape recorder and I would ask him about the why and how and what of it. An old habit perhaps. As I grow older, my relations have become increasingly professionalized, drawn to some purposeful end, connected invariably to work. Ten years ago a first book of interviews with Canadian movie artists released, and next month another will arrive at last, owing to the grace of Coach House Press. It is much too large (more than 300 pages, ridiculous) and contains too many artists (27), but Mark never sat to make his film, and we never got to have our talk. So while our time together has shaped much of what I know and understand about movies, and thereby underlines many lines of questioning in the book, his own words are offscreen, off the page, once again invisible. If only he had. If only I could have. If only he hadn’t. With a deadline hanging over us, we might at last have begun to talk about some of the things we had left too long in the dark or allowed pictures to say in our place. Will I find the words with those left behind, I wonder, the words that will be nowhere recorded or part of anyone’s record. Not the first words—it is too late for that—but some small words of kindness that might offer an opening for those who like to sit in the back row, silent in their own darkness, waiting for their chance, their turn.

(April 2008, commissioned by Shaun Smith for the Pages Bookstore Website)