Exile: an interview with Martha Colburn

I look at her work and think: oh, that looks like fun. Even if the bile is running hot and yellow and streaming from the guts of some model-turned-skeleton there is something about the post-punk soundtracks, the hand-made, Disney-in-a-kitchen-sink approach that draws me right in. Yes, the people have turned into monsters, the skyline is ablaze but my foot just can’t stop tapping to the a-go-go beat.

One thing is for sure: she is hard at work, all those excitable action figures twitching and breathing their next to last, and vomiting flames and torn apart and put together again, it’s all happening one solitary frame at a time under the hot lights. Here is a cinema of restless transformation, the camera pushed up close to the action, and inside that small arena she unleashes all of her profuse energies and lets them run back into the lens. From this prodigious outpouring she has turned from Americana erotics to Dutch dreams and lately to more overtly political matters, rubbing her hands into the dirtied spawn of empire.

MH: I’m wondering if you could talk about how you got it all rolling. Could you set the scene? Weren’t you living in Baltimore, a city not known exactly for its fringe movie scene (or is it below the underground)?

MC: I actually got ‘rolling’ in the local south mountain fairs where I grew up in PA. From there, to Baltimore. I had a band (duo group The Dramatics) and did other musical projects on the side with groups like The Pleasant Livers. Through living with musicians and co-operating a record label we released six Dramatics records and went on tour in Europe. I was surrounded by musicians I liked and made films to their music and my music. Musicians from all over the world would come to our warehouse and get shut up in there with us. It was an inspiring place (with no heat). I basically froze for ten winters. I made about thirty films and 5000 hand collaged record covers, so I felt the groove there, but it was a scary place. It wasn’t so much “below underground,” as it was Hell on Earth. Movie scenes there was not. I was hanging with musicians from other parts and worked at a funky cabaret featuring the local talents of assorted characters who were all great.

I made my work on the floor. I set up my dad’s old tripod, taped the corners (one duct taped with a brick to hold it down, and animated on the floor this way with a super 8mm camera). That’s the set-up. I did the painting and collaged materials, then filmed it. I made like thirty some films like that. To mix it up sometimes I made fake commercials starring my friends, or a drag-striptease, or the pet ducks (that lived in our sink) would make a music video that was supposed to be taking place in the Knitting Factory. We just had fun. New York freaked me out, even though I had hardly ever been there because I thought it could threaten one’s creativity with its consumer culture and high rents. That kind of bull-headed, close-minded, anti-social attitude can have positive results. Go with it if that’s what you’re feeling. I created a self-styled kind of creative temporary utopia with all my musician friends and then boyfriend Jason Willett and roommate Jad Fair (when he wasn’t on tour). I then moved to Europe and could not find that “place” again. Now back in America I have managed to find it again, in this old speakeasy bar that was in the 80’s for a moment called EXILE; Klaus Nomi and Blondie played here. So yeah, I live and work out of a place with a huge sign that says EXILE on the outside of it. Need you say more, right?

MH: The pictures you use are often written or painted over, like graffiti. The figures (most of your steals are figures, faces, bodies) are tagged and Colburned, brought into your world. I’m thinking of the cat heads on pin-ups of Cats Amore (2:30 minutes 2001) or the fangs you’ve given cheery advert pitch girls in Evil of Dracula (2 minutes 1997). Like taggers, ‘the original’ is still there, the same way a spray bomber would leave a train or building behind, only marked now by your visit. Do you see a relation?

MC: I never directly thought about graffiti. Currently I am thinking about the physicality of what I am filming, the broken piece of glass I once used to do paint-on-glass animation is used, a piece of random paper from the street, the physical texture of the world around me enters into the picture.

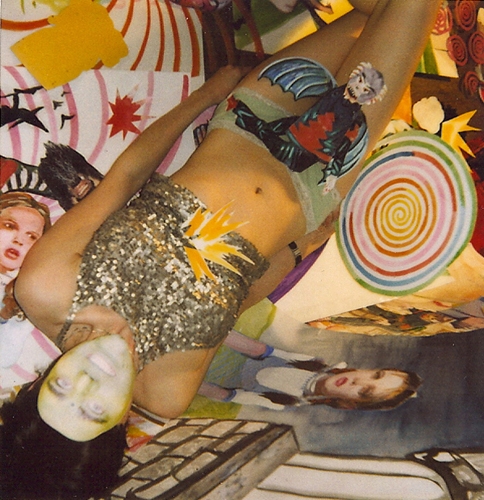

MH: In Skelehellavision (7:40 minutes 2002) porn images are painted over (often with skeletons and flames), a skull faced cop degenerates into blurred colour smears, snakes churn out of navels and into crotches, and images repeat and re-circulate in this frenzied mash up. How did you make this movie, where did these pictures come from?

MC: I found these pieces of film, which I manipulated in a thrift store, next to the last erotic theater in San Francisco to show film. They closed and I found some of the discarded footage. The rest is animated, flat puppets floating on glass over black and then superimposed with footage of a volcanic flow at night. I did those scratched pieces in projection booths and trains at night, on a film tour in Europe on a mini light box I carried. There are hand scratched skeletons on each frame and flames and dots and lines.

MH: What does it mean to paint skeletons onto a series of pin-ups? (Is it a reminder that these people are older now, perhaps dead?)

MC: There are a lot of Bosch-like demonic scenes combined with these pin-ups. It marks a transition where I started doing research on particular subjects and working it into more thematically related films. I researched the idea of the afterlife for this film. I combined these historical notions of “fantasy/Hell/afterlife”.

MH: In XXXAmsterdam (3 minutes 2004) you re-animate painted figures from centuries past and let them walk the streets again, adding to the fevered cultural jam of torn up streets and pin-ups, police women, clipper ships and drugs. But don’t these fleeting impressions run only surface deep, like the restless changes on television, giving us no time to look at anything?

MC: Yeah they do. They are surface deep! It wasn’t made as some masterpiece. It’s like a public neighborhood film for this place called the Baarsjes where I lived for a time, and I had to get a ‘neighborhood grant’ from The Stadsdeel de Baarsjes to get out of some slippery back-rent problem I had incurred at this ex-dental office I was living and working in. It’s made as some kind absurd portrait of this area. There’s absolutely no defense for it. At the time it was essential that I make it, to make it to live, to make a better film, etc… It actually shows quite often in Holland and the Dutch Filmbank, which is so awesome, distributes it.

MH: How does this film and A Little Dutch Thrill (2 minutes 2003) (where a series of pin-ups are painted over) convey your sense of Holland?

MC: I was friends with the drummer Wilf Plum, in a band, he used to be in The Dog Faced Hermans that played with The Ex occasionally. Well he had a band (Luana Flu Winks) and they or I got a grant to make a film, and that’s what I made and turns out it won first place at this Dutch short film series, I forget the name of it. It was just for fun and to survive at the moment. I based it on a Belgian magazine called Gandalf, which was known for its satirical take on culture/sex/politics.

MH: How was your move to Holland? What was it like to be there as an artist?

MC: I moved there on a two year art residency at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten. I moved to Amsterdam in 2000 and traveled a lot to do shows and escape the weather and the terribleness I felt living there. I got a lot of work done and really have to laugh at the absurdity of the very particular forms of misery I experienced there, especially watching these Bruegel and Bosch documentaries lately while I work on my new film. At one time I lived with a junk dealing philosopher wanderer that was straight out of a Bruegel painting. New input you know, after ten years in the Baltimore ghetto…

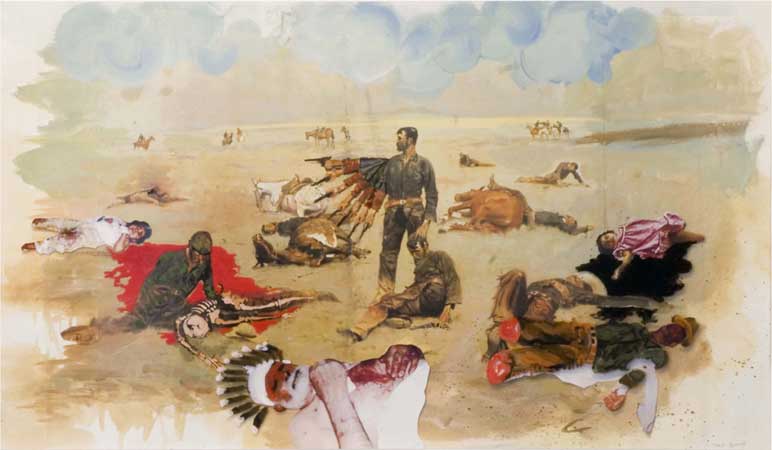

MH: In Destiny Manifesto (8 minutes 2006) early North American settlers dig into the soil of the “new world” and find modern warplanes flying from the earth. Cowboys appear in deserts littered with blood and Native corpses. A Native brave is superimposed over the prisoners at Abu Ghraib, the infamous prison in Cuba where detainees were routinely subjected to torture ordered by the white house. You rewrite the Western as an imperial line that runs from Native genocide to Iraqi invasion. Can you elaborate on this relationship?

MC: I was interested in examining these two disparate battles visually and emotionally. How these times of historical crisis have been created and edited for us visually and emotionally, to support. Not unlike the whipping post, which in early America appears as a symbol of ‘our’ suppression of liberty. ‘Our’/America’s assertion of liberty is inter-changeable with the suppression of liberty. The film is physically crafted to contain (in its form?) the idea that we are fighting our own past in America: places replace places, jump time, lose their place, things dissolve into one another, re-appear in another time, etc… Some paintings of the Wild West were little more than staged ‘fictions’ found in art depicting ‘wild west’ cowboy impersonators posed on the roof tops of buildings in Brooklyn. When I looked at the paintings of Remington, Charles Russell, George Catlin it was as though the infinite landscapes portrayed or recorded are as unreachable as the truth within the history. These images extol progress and in the meantime cover up the hardship and suffering and conflict, which come of it. The chaos and wildness of Iraq has been compared to ‘the wild west’; money filled footballs stored in secret caves, improvised banks, lines of tanks or wagons receding into the distance, lawlessness, smuggling, stockades, assassinations… The film is a manifesto about the feelings of destiny in American culture but now the destiny is taking us East, as opposed to West. A manifesto/essay/documentary/animation/painting.

MH: Do you feel that because of the length and style of your movie making, it will inevitably play to audiences already hip to the message (do you worry that you are ‘preaching to the converted?’)?

MC: Well, I’m not preaching. So, I see it as, well, at least people outside of America see a work from America that is, not specifically anti-Bush, it is however looking at something in America’s motives which, in certain instances, are very destructive. There’s a lot of Anti-Americanism, even among what you might think of as well informed people. Expressing your ideas, especially politically, should be done without reservation. My work is not seen in the seclusion of the film circuit of animation, or the art world, or the underground cinema scene. I go to extra lengths to send my work for screening specifically in places which are ‘out of reach,’ like Spokane or Korea or little towns in Europe.

MH: Meet Me in Wichita (8 minutes 2007) is an upended version of The Wizard of Oz, with O___ B__ L____ recast in most of the major parts. After a hurricane sends Dorothy into the nether world, Iraq is bombed and D walks horrified through its ruins. O____ appears as the tin man spouting oil, the wicked witch whose cat attacks D’s Toto dog, a hunter who shoot D. At last O____ is killed by falling bombs but his ghost causes a black rain to fall. Oil uber alles. Why this fairy tale of American foreign policy, and the B__ L____ riffs?

MC: (THE O-B-L IS NOT WRITTEN OUT BECAUSE,,,,,MY WEBSITE WAS INVADED ONCE BY AN (I assume) EASTERN GROUP or person THAT TOOK AWAY all MY FILM clips AND PUT UP A PAGE OF SKULLS SAYING, DOWN WITH EASTERN SITES! DOWN WITH THE USA! DOWN WITH DENMARK! THE NETHERLANDS ETC… SO I THINK IT’S BEST TO LAY LOWER ON THE RADAR? SOUND CRAZY? Well, the world is crazy now, and this was around the time of those scandalous cartoons coming out of Northern Europe.

Firstly it’s interesting to note that The Wizard of Oz was written as a political fairy tale. I thought to look at school play production pictures, then realized how much America uses this tale to escape into. How they are recreated with a sense of urgency and thrifty crudeness over and over. Regular people create the Oz that takes place in American living rooms and schools. How different these play productions are from the media machine which creates the other fairytale of politics. It’s all an escape and it’s all real and imaginary at the same moment. Hollywood and your living room and the school cafeteria dissolve into one another.

For the filming of this film it was in the 100’s of degrees in New York City. I have no air conditioning and have to cover my windows from the light outside to film. I had, for the first time, assistance filming because of the heat and the ‘animation stand’ (resembling a hunter’s bird stand) required me to climb onto an old safe to look through the camera and press the button very, very carefully as the camera is basically suspended on the end of a horizontal two by four jutting from the wall which shake if the button is not pushed in a particular way. So I had interns help me, that somehow came from other States, like remote parts of Virginia and Massachusetts. Had these once-strangers sleeping on my couch not been prodding me to teach them to animate in the sweltering heat while they’re on anti-A.D.D. meds and there’s no stopping their focus, and they’re bossing me what to do next with the damn puppets and paint, I don’t know how I would have made it. There are backgrounds that are three by six feet and hundreds of little pieces. Fun nightmare.

I was listening to Glenn Gould a lot while making it and thought to have piano on the film. By calling a few friends in California to see if he knew a pianist, I found V. Vale, who is also the editor and founder of Research (books) in San Francisco. I mixed his piano improvising with sound effects made by Jad Fair, who has been a long-time collaborator.

Meet Me In Wichita is an indictment of America’s dangerous foreign-policy naiveté. The film is a play between fact, fiction, politics, fantasy, terror and morality. The film features Osaka (as several characters from the Wizard of Oz) and Dorothy in a battle of dark forces and faces of Evil. It’s a dark film, not unlike my earlier work, but it is painted in pastel and cheery almost fluorescent watercolor colors. I’m making something dangerous sweet, something dark light, something violent friendly.

Why make this film? It was my expression of frustration with the fairy tale political times we live in, with ‘smoke and mirror’ leaders, faces of good and evil, and so on. I took these ‘dark forces’ rendered for us in the news everyday and placed them in a candy-colored land. The narrative approach is not something I do often, but in this case it’s a narrative that is sometimes nonsensical and childish in a way. Dorothy, for me, is America. Bin Laden is our current ‘face of evil,’ and he fills all the roles like a chameleon. It’s a film that plays with guilt and innocence and icons and how we put a face to the idea of ‘Evil,’ be it Indians or women or Bin Laden etc… what’s the next new ‘face’ of the enemy?

Meet Me In Wichita is like a note in code, an answer to the question “Where is Osama” He’s in our imaginations. The power he has in people’s minds is far greater than anything the man is capable of. So there is no answer, but everyone would like to think there is. That’s why I made this film as a loop. There is no end, the wizard is not revealed for what he is, Good does not win over Evil, Dorothy does not find her way home.

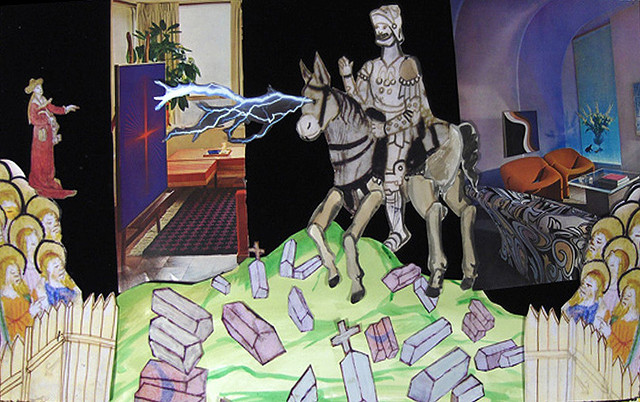

MH: In Don’t Kill the Weatherman (2007) a pair of medieval figures cut down trees with chainsaws while owls look on. A naked man emerges only to be sliced to bits. A lightning bolt upsets the scene and Christ on the cross replaces the tree. Winged trumpets greet him and are zapped by bolts. A monk driving a car runs him down and then some deer fall under the wheels. Two devils gas him up, then he is taken to heaven while his vehicle goes down in flames. There is much more in this biblical retake, including melting glaciers and the Ark and industrial pollution. This biblical drama of ecology recasts global warming as biblical legacy, what led you to these themes, why the chainsaw nuns and why the title?

MC: This film was made in collaboration with the Rosenbach Museum and I based it on an apocalyptic 15th-century French Illuminated manuscript ‘Guillaume de Deguileville’ in their collection. It was a moralizing Christian tale. If you look closer the naked man is chained by his ankles to the tree and represents a ‘tree-hugger,’ you know… like the environmental activists who chain themselves to trees? There’s a debate amongst Christians now about the immorality of energy use, specifically in affluent nations. Richer nations produce far more carbon dioxide than poorer, but the poor will sooner suffer the consequences. Ranging from insect-vectored diseases, increased floods, droughts, and hurricanes, the Plagues! The floods! The end of the World as we know it! I called it Don’t Kill the Weather Man! As if it is a statement that your average American may say to another (if they were eco-conscious) but also a variation on the Greek saying ‘Don’t Kill the Messenger!’, the messenger in this case being he who tries to bring the bad news of things to come, environmentally.

Nothing can be done unless it is through the mediation of the computer… I say to that: I will not be brainwashed. I’m a big supporter of the real world, yes, and it’s funny that that could be political in any way, but it is. The idea of ‘digital versus analog’ is for me not a question of finance or image quality, but has to do with the soul of the work. I’m working now on a film dealing with drug addicts and Puritans. These groups both ‘tweak’ in the spiritual and physical world PLENTY without ever using computers. As I work on the puppets for it, making some 600 hand-made hinges for preachers and pushers to be assembled, and fifty foot long painted backgrounds, some with five moving layers, and moveable fingers to grab at their Bibles and Meth pipes, I am in a way having to do work in the same way my subjects might obsessively take apart a stereo over and over or read the Psalms obsessively. The physically obsessive nature of its creation is in tune with the subject.

The techniques I am interested in exploring, for instance the multi-plane-glass-with-3D-panning-background animation technique, was never really developed much after its invention at Fleisher Studios in the 30’s. Watch the old Popeye’s. I’m not interested for some quirky retro reason, and certainly not for ‘hipster’ points. It’s just that for my work to technically grow (since I work completely manually/physically) I have no choice but to look back in time for information. With the introduction of computers and video, innovations in the way I work came to a halt, so it’s an endless field for me to invent technically and discover new things. Without ten guys in lab coats, and Disney’s money, I am coming up with these ghetto fabulous, more and more complicated animation stand-rigs, made out of hack-sawed shelving metal-bolted together. I’m with the animator Bruce Bickford when he said something to the effect of “the world should just make movies and then there wouldn’t be wars or waste or all this mess”.

Like Taking a Group of Zombie Pack-Mules Over a Mountain: A conversation with Martha Colburn by Roberto Ariganello

Martha Colburn, the queen of defiled filmmaking and bastardized animation, begins an artist residency at LIFT on September 29, which runs until November 12. Since 1994, Colburn has created more than 35 films that all remarkably blend pleasure and perversity. She has been hailed by such icons of independent cinema s George Kuchar and Jonas Mekas as an artist that has developed a style that is visually unique and a film language that is wholly original. Colburn has developed a number of devious techniques that deface, corrupt and decontextualize films and images of pop culture to create a unique and disturbing alternate cinematic universe. As part of her residency at LIFT, Martha will be sharing some of her expertise in a collage animation master class entitled “Collage Collisions,” starting November 3. Check out the LIFT website for more details. As well, LIFT and Pleasure Dome will present a retrospective of Martha’s films on Friday October 29 at Cinecycle. The following conversation took place via email.

Roberto: Tell us how you started making films.

Martha: There were two points of starting. The first was literally finding “found footage” and projector and splicer at the city surplus dump and completing films by manipulating images and pre-existing soundtrack, and the second was crating original footage. I began with only the means to edit, project, hand-colour and razor blade up the frames. Yet this was enough! This was exciting! Making movies without having to be a filmmaker first! I did things like trying to hide Old Yeller’s face (from a Disney trailer I mutilated) with a blob of black ink (under the illusion that this would provide some legal protection), cut frames into six pieces and reassembled the film; hand-coloured and manipulated the optical soundtracks; learn to identify certain words from the optical track (visually) and re-edited the text/sound effects. Tired of hand scratching titles or cutting out individual letters of existing titles and taping them onto the film to create my own titles, I started to animate super 8.

Roberto: How did you hear about LIFT, and what do you hope to accomplish during your residency at LIFT?

Martha: I was feeling desperate one day and came across your info while searching the internet. I was in search of a place to make my next film, a place to get some energy, a place to focus (from away from the Dutch Immigration Police). I see my time at LIFT as being dedicated to exploring new formats and approaches to filmmaking and exchanging information with people… expanding ideas… some Neurobics (a new word I learned). I like the idea of a residency combined with teaching workshops and screening work.

Roberto: What was your understanding of collage or animation when you began making films?

Martha: Zero. If you can hit a stopwatch, move the paper, stop the stopwatch, break that time down into 24 frames per second, you’ve got it. The biggest challenge came when I decided to make a spider film after painting all these beautiful spiders, and realizing that I didn’t have enough hands to move all the legs at once. Once filming, it’s about concentrating on which direction each leg (or eight) is moving. Jointed snakes also offer a challenge. A chimp could make collage animation.

Roberto: What attracts you to film?

Martha: It may be as simple as “spinning wheels.” My whole childhood was spent working for hours on end helping my father repair old broken tractors, using turn-of-the-century farm equipment like manual corn-huskers and drills and tilling machines. Film is simple in its making and projection. Equipment (in the low-budget world of 16mm/super 8), it is a bit like taking a group of zombie pack mules over a mountain. Legs breaking off, eyes falling out, some go over the cliffs entirely. But with a little know-how and some guts, one can always piece together at least one or two to make the journey – or film. That’s a silly analogy. I just love it. Film is so enticing! It can contain so much energy! So luxurious and yet so simple! And it’s not going to be around much longer!

Roberto: And how has new digital technology impacted on your work?

Martha: Until last year, when people would ask me if I had a PC I would say, “Yes” because I thought that meant, “Do you have a personal computer?,” like one you use at home or something. I have never owned a computer, although I hope o soon. I use a friend’s computer. It’s not hip because it’s a dingy beige and too big to take to a coffee house. Basically, if it can’t be fixed by hitting it with a blunt instrument, it doesn’t belong in my world. Digital oh! Six months ago, I found a digital camera in a hotel room dresser drawer in Frankfurt. I kid you not. My newest project involves paint aniation (whereby you paint on glass and then wipe it away). As I am left with no record of what I have done I take some digital photos while I snap off the Super 8 frames. Digital technology, as I see it, is an entirely different beast than film. I am still not done mucking around in what may well be the final hour of “experimental film.”

Roberto: Do you think that experimental filmmaking will cease in the near future?

Martha: Yes.

Roberto: The soundtracks to your film are as original as your imagery. Describe the process of creating sound for your films.

Martha: In Baltimore I had a duo group (The Dramatics) and used that music and the music of my friends, but that all disappeared when I moved to Holland four years ago. Since then, I’ve done Big Bug Attack to the music of German keyboard-nut Felix Kubin; Secrets of Mexuality to the music of Mexican composer Felipe Waller (played by a Dutch ensemble); and, for Skelehellavision, I made a collage soundtrack. I have two films in the lab now: one that features music by the Dutch band Liana Flu Winksa and one with British trombonist Hilary Jeffrey’s techno music experiment from 1999. Next I hope to work with Coco Solid and Erik Ultimate. They are Kiwis (New Zealanders). I love musicians. They have such good hearts. Usually collaborators are close friends. Charlie Parker once said, “If you don’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn.” I think you can apply this to film as well. It is about channeling our lives into four thousand notes or four thousand frames; it makes sense that somewhere it syncs up. Then pay some money (yes, it hurts) and print it.

Roberto: Your films often employ artwork or found footage from very disparate sources. Describe the process of marrying these different kinds of images.

Martha: Not making a division between the printed/filmed/painted, it’s all colour and image. Sometimes I hijack commercial images intended to alter my thinking and turn them inside out, to vex them, to rob them of their assumed power. Sometimes in my films I express love and reverence for things that others find disturbing. I often find disturbing images which were created to be beautiful/sexy/comforting, etc. It’s a game with imagery and imagination. I try to get a lot of angles on one idea, and, usually, the found or the invented alone don’t feel complete to me. I then go about fusing them together through colour timing, handmade special effects, cutting, etc. Plus film is this physical material. It grows like a stringy fungus out of all my boxes and shelves and jacket pockets. The footage I create has the same physical form as this found footage, and I relate to them as a single universe in many ways.

Roberto: As a body of work, your films crate a dynamic, disturbing and personal universe. You seem to have created a new visual language. Is there a personal narrative logic to your films?

Martha: Strange thing, animation. Piecing together this dense and fast moving and intricate universe, but so slowly, each 1/24th of a second contemplated and carefully constructed. It can take so long to get to the point of seeing sound and moving image together that the film becomes independent of me. I sense this with my body of work as well, a disconnection because I am always moving so fast and working so hard. With my style of creating animations, I can think and see and say all sorts of things, but the end result always surprises and is strange to me. The logic is there afterwards and the personal is a given and the narrative is constantly expanding.

Roberto: Your films are consistently imbued with a humorous yet menacing violence that seems to follow a dream logic narrative. What is the role and/or attraction to violence in your films?

Martha: The violence which comes out in my films is not pre-conceived. It is a reaction to my (past) environment. I went from the horrors of backwoods’ secluded weirdness to the horror of a rundown and desperate city centre in bombed-out Baltimore. It just seemed the course life took for me was in these environments, and I was left to cope with them because my head was always so much in my work. The violence and deformities and utter despair of it all was completely frightening and entertaining at the same time. I can’t be objective about my sue of violence. It’s something that I was saturated with. Certainly the impact of it in my films is much less than that of freshly splattered blood on the streets. I use my work to get control of whatever is at the present moment out of control and to express my anxieties and to delight in it.

Roberto Ariganello is LIFT’s Executive Director and a filmmaker currently trying to find the time to finish a documentary about the repercussion of one violent day in his grandfather’s life 63 years ago.

LIFT Volume 24, Issue 6, November 2004.