The Death Dances of Michael Brynntrup

Michael Brynntrup remains the most fiercely prolific filmmaker of the German fringe. In his twenty year tenure he has produced some fifty films including two features, in which he has undertaken an exhaustive cinematic self-examination, conjuring the subject as a fictional amalgam of semiotic slippage, male/male desire and broken historical recall. His production is haunted throughout by death, a theme whose origins recall the filmer’s own, when he shared the womb with a stillborn twin. This early join of life and death continues to impel his relentless pursuit of cinematic invention.

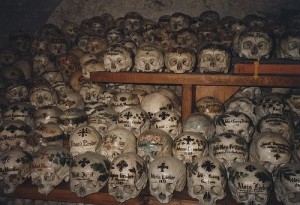

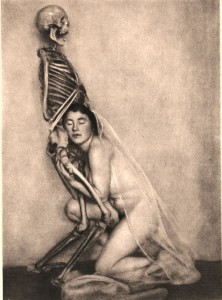

In 1988 he began work on a cycle of ‘Totentanzes,’ Death Dances, eight in all, gathered beneath the title Der Elephant Aus Elfenbein (The Ivory Elephant) (45 min 1988-93). Together they unfold a catalogue of psychodramatic rituals, a series of theme and variations Bach might have named The Art of the Skull. Photographed entirely in super-8, each figures a single performer, a skull and a specific arena of interaction. The first depicts a young girl at play in her garden, photographed in a casual home movie style. There is nothing to suggest, at least initially, that this is anything but a sentimental punctum of the family. But in this garden she finds a skull which she fills with water and drinks from, the two heads merging in the act of libation, before she bears it back to earth, using it to water newly planted seedlings. This evocation of growth and decay, of the deeply felt complicity between life and death, is demonstrably understood by its young protagonist. Indeed in the film’s evocation of life cycles Brynntrup suggests that this is the legacy we are born into, that in the garden there is already death. Its Edenic overtones are clear, the bright light of day contrasting with the film’s darker themes, the poles of innocence and experience made to marry here, beneath the sign of the skull.

In Totentanz 2 a crimson tinted flood is superimposed over a magisterial robed figure, an Aryan blonde seated as if on a throne. He finally unveils the skull, heats it over candlelight, and begins to add powders and pewters from his table. These he grinds together with a pestle cast in the shape of a woman. Returning to the candle he sets his brew alight and offers it to a nameless God in a gesture of supplication. Photographed entirely in the black surround of a home movie setting, with the onrushing waters of Dis swarming over the whole, this incantory ritual, despite its esoteric trappings, is replete with a calm dailiness. It comes as an admission that our understandings owe a debt to, are leavened and clarified by, the certitude of our own end.

Totentanz 3 again features the trope of superimposition, now showing five skulls turning in a grim circle over a man who loses his hair. He gropes in darkness, panicked, his gestures slowed through rephotography, and begins a histrionic dance of anguish. Totentanz 3 turns about the Christian figure of conversion, that moment which divides a life into past and present, which occasions many of its adherents to speak of a former ‘dead’ life and the unmistakable feeling of being born ‘again.’ Here a flesh elegy unfolds as the realization of his own mortality, his own limits unfold, emblematized now by his lost hair, compelling him to dance.

Totentanz 4 is the longest of the death dances, and the only one to feature language. It begins in black, with a voice (lifted from a training tape on sleeping) enjoining the viewer to sleep, and then to dream. Both voice and intertitle ask: “Please close your eyes”. The voice continues: “All thoughts are now absolutely equal.” And then we are admitted to the film’s first image – an atomic explosion, conjuring its own version of democracy, where all lie dead. The voice continues, urging the viewer to relax, to let the world pass by. “Calm. All is calm in you. Nothing else than calm.”

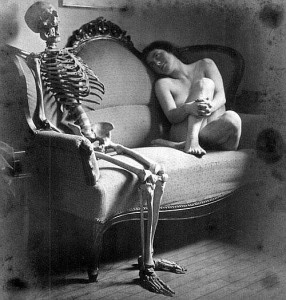

The skull appears in a superimposed pan over a nude male, set in place of a blonde crotch, where a dreamer turns in solipsistic reverie. In his first dream, he appears dressed as a woman and finds a skull in place of love. The film returns to the dreamer, curled asleep in fetal position, waiting for his imagination to take shape. His image now appears doubled, signaling his entry into reproduction, his dreamed double lying atop his sleeping prone. A final dream begins, a fragment from Laurel and Hardy. Entrusted with the delivery of a pie truck, everything that can go wrong soon does, each interaction leading to confrontation and then release into comic violence. A vast pie throwing fest erupts, before we return to the sleeper, circled now by the skull, and a final intertitle: calm.

The dreamer founds a sleep born of escape, not restfulness. While he tries to manufacture relations, possible moments of meeting, these are thwarted by substitution on the one hand (the skull replaces the image of his lover), and doomed metaphor on the other, the slapstick spectacle leading only to aggression. The turning skull superimposed over the Hollywood image insists that these farcical interludes must also lead towards and arise from a deep consciousness of the death of these comedians, that comedy and tragedy share the same dream. Even in sleep, the filmer remarks, there can be no escape from the body’s inexorable status as doomed vehicle.

Totentanz 5 narrates a magician in solitude, alone in a world charged with a few supernal objects which are made to stand here for all that is left out, for what cannot be said or no longer imagined. It begins with a bird cage, another of the talismanic icons of the Brynntrup oeuvre, which reveals itself in a slow zoom. A skull appears, and then a reflection of leaves in water casts itself across his actions, lending a flickering, fiery cadence to the proceedings. The magician conjures a bird, and then a skull which rises and floats towards the cage. In this psychodramatic brief it is the power of death that is at stake, the forbidden pleasure in imagining that we might be able to control the circumstances of our own ending. The cost of this knowledge is the unmistakable isolation of its protagonist, made to leave behind the discourse of an everyday world.

Totentanz 6 returns out of doors. Shot in a high weeded field, a gnome-like figure picks his way through a flourishing vegetable life until arriving at the ubiquitous skull, now covered over with swarming flies. He rubs his face against it in a gesture of sympathy, replaces an eye, and picks out the bloody entrails which remain in its cavities. Obsessively he begins to clean it, to try to restore it to a pure skeletal state, to separate it from its life as meat, but is unable to do so. Frightened, he flees, the skull now reappearing in a crimson overlay haunting his depart, threatening his every movement. Forced to return, he forms a kind of flesh altar around the skull, acceding to its demand to partake of this world and the next, before clambering up a nearby tree and waiting, frozen against the afternoon sky.

The skull’s traditional bone-on-bone iconography signals for the gnome its separation from the natural world he inhabits, signals perhaps a destination or afterlife quite apart from this one. But this acceptance, this pact between worlds is broken when he is confronted by the specter of finality inhabiting his traditional haunts, his home. The skull’s sudden appearance disrupts his customary traversals. In the end his negotiation is less acknowledgment than submission, unable to muster a cosmology which can embrace the skull’s join of meat and bone.

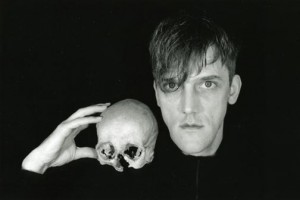

Totentanz 7 is an exercise in portraiture, depicting a solitary narcissist joined in a duet with a skull he imagines to be his own. Red fabric billows throughout in superimposition, while the man flings a red veil over the skull, transfixed by images of himself which appear in polaroid dissolves. He contemplates the skull, and then a series of frozen mannequin faces, while a digital counter issues an accelerating addition. He spins the skull on a stick, dancing together, then holds it before an ornate mirror. This proves to be his undoing. Without warning the film erupts in a cavalcade of superimposition, five images of his mirrored reflections now appear at once, his own face multiplied through his interactions with the end. Facing a final frontier, he loses his boundaries, subject now to a terrifying multiplication which threatens to overwhelm him. Desperately he tries to fix his portrait, his single visage, in a series of Polaroids, though the film implies he has already gone too far, that his attempt to reproduce himself in order to cheat death is doomed to fail. This meditation on doubling is also a reflexive gesture, aimed at the very heart of the movies. In the early part of this century there were placards surrounding the burgeoning new medium of film which announced that with the advent of sound and colour, death would be no longer final. Brynntrup here challenges this notion, insisting that reproduction is not a cheating, but an admission of mortality, and that one may find its impervious stare behind every picture, waiting to claim its inhabitants.

Totentanz 8 returns to the figure of a young woman, perhaps the young girl from the very first film grown older. She climbs a V-necked stairwell, lighting on a birdcage stuffed with bird feathers before flinging them into an open courtyard. She appears again in an immense, emptied warehouse space, the image now re-photographed and solarized. She begins to dance through this fantastical silvery sheen, this veil of abandon. She recalls for us that death is also a place for celebration. Her frenzy spent, she rests in a large window opposite the skull, continuing to cast feathers. She takes up the skull and kisses it long and longingly with her tongue. Hers is a final embrace and acceptance, an eroticization of death, a romantic fury. In the end, in the film’s sumptuous closing image, she casts feathers out the window in a storm of solarization, the light pouring through its aperture in a silver storm which suggests another world waiting beyond.

Each of these films signal a negotiation with ending, with an underlying mortality that informs as subtext the actions of the everyday. They are at once elegies, testimonials and reminders that the end is just another beginning after all, and that the cost of understanding is the foreclosure of an unbending certitude. This too, at last, will be borne away by the reaper.