Michael Snow: Machines of Cinema (an interview) (1993)

Michael Snow is one of Canada’s finest contemporary artists — a blue-chip conceptualist whose widely ranging talents have launched him across a number of artistic terrains. Every month he can be seen at the Music Gallery fronting the free jazz ensemble CCMC. His celebrated public sculptures adorn Toronto’s largest shopping complex as well as the downtown sports dome where giant bronzed figures entitled “The Audience” gape out of the stadium. His paintings and drawings hang in collections around the world. He has produced records of sound art, books, holograms, slide works, and photographs. But nowhere has his production been more elegant, or the effect of his entrance so profound, as in the cinema. Here he has founded a body of work that spans some sixteen films over thirty-five years. Ranging in length from seven minutes to four-and-a-half-hours, many isolate and elaborate a unique quality of the apparatus — the zoom, pan or tracking shot for example. No one has taken McLuhan’s dictum more seriously: that the medium is the message.

MH: Many artists speak of their beginnings in theological terms — that some moment of revelation occurs, prompting a conversion into a new vocation, their art. Did anything like that happen with you?

MS: There are two or three lines. The first one is when I got the art prize in high school, which surprised me because I didn’t think I was doing much more in class than throwing spitballs. But it seems as if I’d been drawing all my life and the teacher noticed that it had its moments. It’s amazing, isn’t it? One person’s gesture. I decided to go to the Ontario College of Art on the basis of that. I took what was called a design course because I didn’t have any orientation about the particular kind of art I would do, although I was already worried about making a living. Apart from the stuff we had to do in class, I started to paint and showed the painting to the head of the department — John Martin. He was very interested and we talked, and he suggested books for me to read. One of the few places to show in Toronto was the Ontario Society for Artists, which had an annual group exhibition of members, and non-members could submit to a jury. He suggested I submit to one of these shows — which in itself was quite surprising to me — and both my paintings were accepted, which had never happened to a student before. The other thing is music, which I started to play in high school. I got interested in jazz around 1947. I started playing piano. I was very moved by Dixieland jazz/blues and met a bunch of other ne’er-do-wells, and we formed some bands and began playing jobs. When I got out of art school I didn’t know what to do, so I took a miserable job at an advertising agency, saved my money, and went to Europe. I went with $300 and stayed a year and a half, feeling very suicidal. I hitch-hiked to cathedrals and galleries and made thousands of drawings. I came back in 1950 and, as usual, I was miserable and broke and still didn’t know what to do to make a living. I was invited to show some of these drawings in an exhibition with Graham Coughtry. I got a call from a guy who thought that whoever had made these drawings must be interested in film and, if I was, he’d like to meet me. This is true! His name was George Dunning, and he and some others had left the National Film Board to form their own film company — he’s the guy that later did Yellow Submarine for the Beatles. He gave me a job though I’d never done anything in animation before. It turned out that Graham got a job there too, and Joyce Wieland was working there already. George was interested in having people there with a fine art background to do animation, which he thought of as an art even though they were doing commercials. That was my introduction to film — from the inside, its mechanics. Whereas I know a lot of other people came at it because they were moved by something they saw — or they loved the experience of the theatre. I never felt that at all. That kind of experience happened for me with music and painting — where I was so moved by something that I wanted to do the same thing for other people. Because of George’s crazy ideas, the company didn’t do all that well. In fact, he made me head of the animation department. And I was playing a lot of music at night. A few months after he made me head, it collapsed but I made my first film when I was there. It was a film just to make a film called A to Z (7 min b/w silent 1956). It came from a style of drawing that I developed when I was in Europe using blue ink, pen drawings. It wasn’t so much drawing from subjects but from imagination, and I decided to animate them. When I made my first film, I didn’t know there was such a thing as experimental film, though I’d seen some of Norman McLaren’s work because George had shown us examples of what could be done in animation. But I didn’t know of it as an area. Since I was working in the film business, and even though I’d made a film myself, I thought of it as an expensive proposition, as a business in a way, so it didn’t seem inviting.

For about a year and a half, I worked every night in a Dixieland band led by Mike White. It was a fantastic band, and I also had groups of my own, which were called Modern in those days. I played every night, and by eleven every morning I could get to my studio where I painted. This was between 1957 and 1962. Joyce Wieland and I got married, and we went down to New York to see shows and listen to music. I was more interested in the theoretical issues and the amazing work that was being done there than I was in what was going on up here. I thought if I was really interested in the issues, I might as well go down and fight it out there. So we moved. We knew Bob Cowan, who was already there, and sometimes we’d go down and stay at his place. He was our introduction to the fact that film was done in an independent way. Once he asked us to come down and see a film by these twins that were friends of his — the Kuchar brothers, who were eighteen at the time. It had a profound effect on Joyce, especially stylistically, but I was impressed that these guys just went ahead and did it. I had a business background in film so, despite the fact that I’d made a film, it still seemed to me that you needed an organization and money to make films. And here were these guys who were funny and inventive and just did it. That was what they used to call “liberating.”

MH: What were you painting?

MS: I started with the Walking Woman in 1961, about a year before we left for New York. I was working a lot with figure-ground relationships in abstract paintings and collages, trying to find some way to return to the figure without traditional realism. I got the idea of making cut-out figures that would be put on the wall so the ground for them would be the wall itself. I made a figure out of cardboard which showed a walking sideview figure, and then I realized that it was a template, a stencil that was repeatable. I decided to make variations. Then I realized that the cut-out figure didn’t have to be on the wall of my studio or in a gallery; it could be anywhere. The environment the figure was put in became another factor.

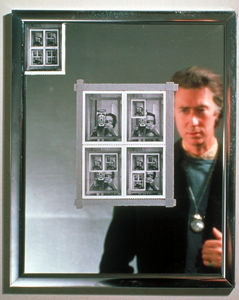

I made my first photographic work based on this walking woman figure called 4X5, which was done in 1962. It’s one of the first photographic works before everyone became interested in photography in the art world. It shows the figure in different environments. It takes a two-dimensional surface which is representational and puts it in a three-dimensional world in order to make a two-dimensional photograph. A lot of things started to fly in my mind about making “site specific” work which didn’t exist then. I also did “lost works,” realizing I could put things out in the world and leave them there. This all happened in the first couple of years, and then I decided that one of the things I was suffering from was that I couldn’t decide what direction to go in. I was trying to clarify myself, to find my own contribution. But I kept on trying so many different things. Then I thought, maybe I should arbitrarily work the same thing over and over again and make my variations within it, and then there’ll be a dialogue between this constant and all these variations, and that opened up the whole idea of sticking with the contour of this figure. Some people argued that I must have known what I was going to do with this figure, that I designed it for the uses to which it was put, which of course is impossible. It was just a drawing I did one day and liked and decided arbitrarily to choose it. I could have done another, or hundreds of others, but I thought I would stick with this one. It shows a silhouette of a woman walking, her hands, feet, and head cropped away, which shows that it comes from a rectangle, that it’s been framed. I reproduced it using rubber stamps and posters and every kind of material I could think of. Then I got the idea to make a film using Walking Woman which was New York Eye and Ear Control (34 min b/w 1964). It was an elaboration of the ideas in the 4X5 photo piece. The film used the different motions of various settings to contrast this static figure. It starts with the figure as an abstract blank, either white or black. It’s a hole in the image in some sense, which later develops to include life through the negative space; that is, real women stood behind the cut-out, and from there it went to these black-and-white images — it’s a black and white film — of black and white people. These are the musicians who play on the soundtrack — and they’re posed against black or white grounds. The end of the film shows a black and white couple in bed.

When I went to New York, I was trying to stop playing. I just wanted to concentrate on visual art because, how much can you do? But it so happened that I met all these people who were doing free jazz, and I loved what they were doing although I didn’t understand it, so I started to listen to them a lot. There had been stylistic revolutions like Charlie Parker’s work — not just Charlie Parker, I hate doing that but that’s what talking is, isn’t it? Saying too little. There was a revolution going on which had to do with changing the source of the variations you played. All early jazz was based on certain progressions — the blues, for instance, had a repeating twelve bar structure, and the variations were melodic and harmonic. These harmonic and rhythmic variations were extended in Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk but still remained within the tradition. Now Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman broke up that constant harmonic background and worked out different ways of variation. In Cecil’s case an interesting thing happened with the rhythm — there was no longer any steady pulse at all. Our studio was where the World Trade Center now is, in a building that’s now destroyed. We had one studio over another. I bought a $50 piano from Roswell Rudd, a great trombonist, and I just made it known that my studio was available for anyone to play. These guys were pretty much hated by the jazz world. They weren’t accepted and had few places to play, so I had these amazing sessions. Everyone played there, and I heard some extraordinary music, and that’s when I did New York Eye and Ear Control. I was basically listening because I didn’t understand how they did it.

MH: Had you met up with Jonas Mekas by this time?

MS: We went to openings in all the galleries and discovered the Cinematheque, which was in various locations. It kept having to move, and it was being run — on the run — by Jonas Mekas. Without Jonas, there would have been no centre — he was one of the people who started the distribution co-op and organized screenings, and his column in the Village Voice was very exciting. The Cinematheque was several grungy, poor people who came to watch films. As usual the art world, the painting/sculptural world, didn’t attend at all. There was a lot of money and excitement in the art world and the work was wonderful too, but it had much more glamour and that never happened to film. The only time there was glamour was when Warhol showed and, since that was part of his game, there were huge audiences of the hip crowd and the next night might be Jack Smith and there would be three people. Through the Cinematheque we met Richard Foreman and Amy Taubin and Hollis Frampton and Ken Jacobs, who was very important in those days. Ernie Gehr wasn’t in the first crowd but after a couple of years he turned up. Hollis and Joyce were there, and we used to go to Ken’s and look at films and talk about things.

MH: What was the response when you showed New York Eye and Ear Control?

MS: It was shown with a film by Warhol and, of course, all his crowd came — they were all in his movie. Eye and Ear Control showed first, and these people hated it. They hissed and threw things at the screen, but a lot of people were really knocked out — Warhol and Gerard Malanga and Richard Foreman were very excited about it.

MH: Tell me about Wavelength (45 min 1967).

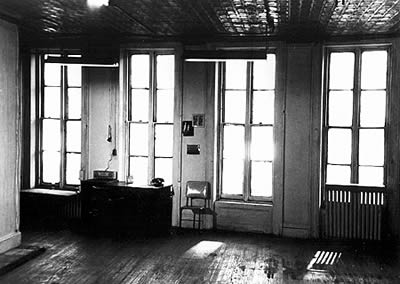

MS: I was working on it in 1966 and finished it in January 1967. It took a couple of weeks to shoot, but I spent a year making notes. A number of previously separated things tried to find a way to resolve themselves. I worked on the Walking Women exclusively from 1962 to 1967 and I was looking for a way out. Wavelength was part of that — it was a heavy thing in my life before it got seen or anything. I was becoming more and more interested in trying to make a kind of temporal shape so what you felt in seeing a film had something equivalent to a sculptural experience. I knew I wanted an extended zoom in a closed space, and it took me another year to figure out how to do that. This film is a continuous zoom which takes forty-five minutes to go from its widest field to its smallest and final field. It was shot with a fixed camera from one end of an eighty-foot loft, shooting the other end, a row of windows and a street. Thus, the setting and the action which takes place there are cosmically equivalent. The room (and the zoom) are interrupted by four human events including a death. The sound on these occasions is sync sound — music and speech occurring simultaneously with an electronic sound, a sine wave, which goes from its lowest rate (50 cycles per second) to its highest (12,000 cps) in forty minutes. It is a total glissando, while the film is a crescendo and a dispersed spectrum — so the film as a whole attempts to utilize the gifts of both prophecy and memory, which only film and music have to offer.

MH: There’s something very live about the film — it lives in the time of the viewing. When I saw it for the first time, it seemed the first film that refused to answer itself — it existed on the screen with an equivalence to how we existed in the theatre. Most films offer a chronology of events, whereas this film hosts the individual chronologies of its audience as they move through the film.

MS: It’s more objective in a certain way, in that the audience gets to examine it. They become interested in thinking about it, what’s going on.

MH: Can you talk about the four dramatic scenes in the film?

MS: There’s the delivery of the bookshelf, the two women listening to the radio, the guy dying, and the woman’s telephone call. Obviously, you know it’s important that there are plenty of other events in the film. When you look at the image of just the room, which is on for a fairly long time, it becomes more of what it really is, which is coloured light on a flat surface. You read “room” but you don’t necessarily read “space” because space starts to flatten over time. So when people people the space, they show you how big it is in the illusory sense. Two guys carry something heavy down the entire room, which gives you an introduction to the thing as a space. Then two women come in and listen to a radio, which is a sound from outside — like the sound of the street comes from outside — but in this case, it’s fauceted through the radio. They listen at the far end of the room so that sets up another spatial relation. They listen to the Beatles song, “Strawberry Fields.” That was done post-sync. When I shot it I thought I should accept whatever came on the radio in the same way that I was accepting whatever was coming in through the windows — the bus goes by, whatever. There was no way I could control that. So Joyce walked in and turned on the radio, and what she got was “Little Drummer Boy” by Joan Baez, which had just come out, and I really hated it; it didn’t help at all. “Strawberry Fields” had just come out and it seemed to be related to what I was trying to do, although saying “nothing is real” is basically stupid; it’s the same investigation of what is real, what is reality. Then the man enters from off screen space. You hear a window being crashed so that space is established by sound in the same way that the radio establishes a forward space in your mind, a belief. Finally, Hollis Frampton stumbles in and falls to the ground. In a sense he joins the inert, and the camera — which is inexorable in some ways just like time is — keeps on moving past him and then he’s behind you. And then when the woman — Amy Taubin — comes in to make the phone call, she makes a reference back in space and time which is now in the back of your mind. [laughs] She makes the reverse of the radio — she makes a contact to someone outside the room which is a spoken, mental thing. After she’s made the call, the shot is repeated and doubled on itself. It’s a ghost, a reference back in time. But it isn’t real because it’s supered on the ongoing reality of the zoom, which is the primary reality of the illusion. You do believe there’s a room there, which is interesting. There is no room, but what is there? That’s what’s interesting about representation. Of course it works, but what is it?

MH: The zoom finally closes on a photograph of waves on the far wall which eventually fills the frame. Was that always part of the design?

MS: Oh yes, that’s what had to be zoomed against. Wavelength.

MH: Is it my imagination or is there a long dissolve at the very end of the film, allowing the still photo to fill the frame?

MS: Yes, I sometimes worry about that. The zoom’s going on and it’s supered against, in this case, the future — because it’s bigger. You know you’re moving toward this rectangle which will eventually fill the screen. So I make it dissolve into the future — it’s sort of like coming. That’s one way to read it. When I finished it, I thought it would be shown once or twice at the Cinematheque and that’s it. Because that’s what happened to films. Then Jonas said there was a festival and that I ought to send this film. I had made the first version with part of the soundtrack on quarter-inch tape. I just thought that it would sound better. But we talked about it and didn’t think it would be a good idea sending it with the tape; it just wouldn’t get shown properly. It should have a mixed track and a new print and I was really broke. So Jonas got the money for it, even though he was as poor as anyone else. It was just amazing. He sent the thing and it won first prize — $4,000. I wouldn’t have entered it without Jonas.

MH: That was the Knokke-Le-Zout Festival in Belgium. Did winning make a big difference?

MS: Oh, yes. It seemed as if the festival had some attention in Europe. At that time there was a sensationalist idea about underground film which got written about in Time and Life, partly because of Warhol, and partly because of the sexual part of it. But it turned out that there were people in Europe who were genuinely interested, and this festival was very well attended, and they wanted to see more. So I did my first European tour showing Eye and Ear Control and Wavelength.

MH: Tell me about Standard Time (8 min 1967). Like Wavelength it features an enclosed interior — it’s like a home movie.

MS: Yes, that really was my home, wife, cat, turtle. I became more and more interested in making the camera a protagonist. It seemed to me that was lost in the films I was seeing. Wavelength made you see a zoom. Normally a zoom was just to get you closer to something.

MH: But its role as a protagonist is very different than Brakhage’s work where the camera is also the protagonist.

MS: The protagonist there is still the maker, because he’s very interested in the translation of touch. I remember seeing The Art of Vision, which really knocked me out, but there were things about it that clarified my wanting to make work with a total shape, wanting the camera, not the maker, to be the story. There’s a tendency for an expressive film — you walk into a bar and you sit next to someone and they start telling you about their life and you don’t want to hear it. That’s something I never wanted to do. I never wanted my work to talk about me. I want my work to exist on its own, to be self-reliant, so you can have a dialogue with it. The expressive use of the instrument, which was what Brakhage was doing, and which I still think is one of the most radical things that ever happened in the arts, was something I didn’t want for myself. His strength clarified my own way of thinking. That’s what was wonderful about being in New York — there was so much powerful work that it was really a sink-or-swim thing. I had to ask what I could do. Standard Time was the second work to begin to explore the vocabulary of camera movement. It uses horizontal and vertical pans from a tripod. The soundtrack came from using the radio (which is visible in the film) as a musical instrument. I “played” it using the station dial, the volume dial, and the bass and treble. The sound imitates, in a sense, the visual movements in the film.

MH: The film seems a duet between two instruments: the panning camera and the panning radio dial.

MS: Yes, the sound isn’t sync — it’s in a parallel mode that features a kind of Doppler effect. The Doppler effect happens when you’re standing on a road and a car in the distance grows louder as it approaches and quieter as it recedes.

MH: Had you already decided that you wanted to craft a body of work around the various gestures of the camera?

MS: Well, yes and no. I was just constantly thinking that there were things that could be done and hadn’t been, and I wanted to see them. That included camera movement but also image/sound relationships. Standard Time was casual, like a sketch, and it really was “experimental” in that I was trying to find out what happened to the image as a result of panning at different speeds. Back and Forth (50 min 1969), the next film, is a grand formalization of some of the effects I learned from Standard Time. It’s also an interior, a classroom, and it’s built first on left-to-right and right-to-left continuous pans with the camera on a tripod. It starts at a medium tempo, slows down, then gradually picks up speed to very fast; there’s a cut to an up and down pan in the same space at the same high speed then it gradually slows down to a stop. The gesture of Back and Forth is a “yes” or “no” gesture and includes such relationships as teacher/student and male/female. The film is about reciprocities, balances, oscillations.

MH: When the camera’s moved quickly back and forth, the whole scene becomes a blur, as if difference is extinguished in the look of the machine.

MS: The velocity makes a unity of disparate things; it’s like E=MC2. You’re right that “difference is extinguished.” The image of objects in the room blurs, and they all gradually merge to become one field of energy. This can have religious as well as physics implications. Back and Forth also features something I continue to be involved in which is themes and variations — in music one of the greatest examples is The Goldberg Variations by Bach, where there’s a statement of a theme and then amazing variations developed from various aspects of its original theme. That’s one of the things jazz has always done and, in another way, that’s what I’ve done in film.

MH: That’s how La Region Centrale (180 min 1971) seemed to me, that you framed a very limited arena within which the camera could inscribe a set of variations. How did it start?

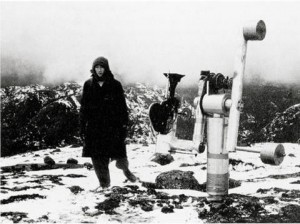

MS: There’s a pretty clear course of development because I saw what happened with circular pans in Standard Time and Back and Forth. Both used interior spaces because they were measurable, and you can believe in them in a certain way. There’s a space on the screen you go into, but it’s also flat. I started to think about exterior spaces and arrived at the idea of making a landscape film that would be a true film, not an imitation of painting. It seemed that what would be properly derived from the idea of doing something outside was camera movement in a totally 360-degree space. I spent almost a year looking for someone who could solve this and finally found Pierre Abbeloos — a technician working for the National Film Board in Montreal. He built a machine to my specs in the sense that I told him what kind of motions and speeds it should be capable of and that it had to be operable through remote control. The main issue was that I didn’t want it to photograph itself.

MH: How did you find the place to shoot?

MS: If it was going to be landscape, I didn’t want anything made by humans, because the peopling of space should occur in your mind. Just like in Wavelength, the space is yours. I didn’t want buildings, because that would be a human form and I wanted the camera to make the form. Because Pierre was building the machine in Montreal, I looked for a place close by, but could never find anything that was practical, that you could get to. Then I realized that I’d probably have to go there by plane. So I went to the government offices in Quebec City and looked at aerial photographs, trying to stay as close to Montreal as I could, but for some reason I lit on asection near Sept Iles, which is on the St. Lawrence, so I went there and rented a helicopter. We finally chose a particular spot and later went back with machinery, and Pierre and this other guy and Joyce, and we were left on a mountaintop. We were there for five days. It was supposed to be four but there was a storm and we couldn’t get back and it was quite terrifying.

MH: So while the camera’s shooting you’re all crouched behind some bush with the remote unit?

MS: There’s a bit of a valley behind the big rock and we’re back there with a generator and all kinds of shit. The remote had a set of dials for each of the functions — vertical, horizontal, and rotating movements as well as zoom and speed. I had made a little score but the shooting became more improvised than expected. Pierre had a wonderful idea for directing the machine, which was to make sound tapes where different notes signalled different functions. He made a sample tape but the machine was unpredictable and it was getting later and later. It got to be August, and we couldn’t get the machine finished until late September, and the location was far north, and I was really afraid of that, and I had other things to do to. So finally I said we gotta go. I just shot one test in his basement to make sure it was working and basically that was it. It was really pretty risky.

MH: These soundtapes are in the film?

MS: I did all that post-sync. Before I went up I had a score that was marked with the kind of movement and the number of minutes it went on. But it was very hard to visualize because I’d never seen it before. In a way it was symphonic — certain themes were stated and picked up again, certain motions and speeds — but some of it was unpredictable because, although I followed the general scheme, some of it didn’t work for various reasons — some of it technical, the light — and I wanted to take particular periods of time which was a problem because of the machine. One time it was cold and we shot a ten minute roll which we couldn’t look at it because we’d be photographed if we did. When we went to change the film the camera was jammed with broken film and we lost a couple of hours cleaning. I would say, well we’ll shoot at three and at five, but it would never work. [laughs]

MH: Were you happy with what you saw?

MS: Yes, it was fabulous. I shot five hours, all different takes of certain movements at different times of day.

MH: You shot ten minutes at a time?

MS: Yes. And if it was going to be sequential, we’d overlap to give us something to edit. I wanted to make a distillation of an entire day, which is what happens. It starts in the early morning, there’s a sunset and sunrise, and it ends again in early morning. The point is, it’s cyclical. The planet moves in a cycle; it’s a circular thing and I wanted that to happen in the film because it’s cyclical too. Its subjects are the sun, the earth, and the moon.

MH: Can you tell me about Dripping Water (12 min b/w 1969)?

MS: Joyce and I had a dripping tap in the loft on Chambers Street, and I just started to listen to it and thought it was extremely beautiful. I decided to make a tape of it so I could examine it a little bit better, listen to it amplified. I’d get stoned and listen to the tape, play it for other people, and it was incredible, especially with the other one going on. The real tap. Joyce had the idea that we should make a film of it. So basically the collaboration was arranging stuff in the sink and deciding it should be a fixed shot.

MH: Is it sync in fact?

MS: No, it’s not. It’s in the sink but it’s not in sync. We did that deliberately because it’s built from the tape.

MH: One Second in Montreal (26 min b/w silent 1969), features a number of black and white still photographs taken in Montreal which are held on the screen for increasing and then diminishing intervals. Why the photos of the snow scenes?

MS: Well, it could have been something else but it wasn’t. One Second in Montreal is about trying to make a film about duration — that experience has to do with the time it takes. When I had the idea I thought of taking black leader and having a punch hole every so often, but then there’s nothing to watch. So that didn’t really interest me. I thought there should be imagery of some kind, but because I wanted to measure periods of time it couldn’t be too interesting. It had to be something that set a state of mind, that gave you something to look at, but all of the images needed to be equivalent so one wouldn’t dominate over another. I had previously received this package of photos for a competition to put sculpture in Montreal parks. They were badly made offset lithographs, badly made in the sense that there was no contrast, little detail; they weren’t too interesting.

MH: These photos showed the sites which the sculptures were to be produced for?

MS: Yes. I really liked them. I put them up on the wall, and there was something about them that really knocked me out. It might be partly because I lived in Montreal from the age of one until I was six; there’s a kind of nostalgia in them in a funny way. They’re all very similar, very routine shots of these parks.

MH: They all seem to be waiting for something.

MS: Yes, there’s something immanent in them. I used two different series to measure the holds: the Fibanachi series measures the holds getting longer, and another shortens them down to one frame at the end. The Fibanachi series goes up incrementally — 3,6,9… — and these numbers shape the time of the film. All the holds are different lengths. Along the way I thought maybe I should mark the change of images by something, and I had the idea of making a sound happen like a click, which I finally did in Presents, where a drumbeat happens on every cut — marking this almost invisible place between pictures.

MH: How did you arrive at the title?

MS: Well it’s poetic in a sense because the still-photo images could have been taken at one-thirtieth of a second and there are thirty pictures.

MH: Your next film also featured still pictures — Side Seat Paintings Slides Sound Film (20 min 1970).

MS: Yes, it’s a filming of a projection of slides of paintings. It’s filmed from the side so they’re not very clear.

MH: Why from the side?

MS: Because I didn’t want you to see through the film to the slides to the paintings and think you were seeing the paintings. I wanted you to see the film. It’s a box in a box of mediums. But what’s really important is that it’s a film. To start with, you can’t see the slides that well because of the side seat the camera’s been given. And then they go through these modulations — the speed of the presentation changes and with it the exposure of the image. The slides are being projected by a carousel projector at a regular rate of change — fifteen seconds for each slide. The subject has an even division like a clock, but it’s modulated by the fact that it’s shot at different speeds. I shot it with a single-system camera, on film which carried a sound stripe. As the slides appear, I read the titles of the paintings, their sizes and dates. The size is interesting because you can never tell the size of anything on a slide; they’re always projected the same size. And while the voice lists a chronology, this span of time is modulated — becoming slower or faster according to a temporal shaping which is only possible in film.

MH: Usually a film tries to replicate the experience of the best seat in the house — you’re always watching events from the best possible vantage. But in this film I’ve got the worst seat, as if I’ve come late and have to sit in the wings.

MS: [laughs] When the camera shoots in fast motion, the voice gets higher and the whole screen becomes overexposed. Now attention is directed to the total image instead of the perspectival habit which leads you into the image. Seeing the entire field is something I’m very concerned with; it’s a problem I first tried to solve in Wavelength. The point is that film implies a transformation of any substance into a new material. Even though in human life scenes of cruelty and sex are the most appreciated because they are the most important in life, they have still become abstracted into something else, into light. That’s why I’m interested in experience derived from the entire field.

MH: A few years back I trooped up to the Censor Board to ask what their rationale was for cutting. They claim to understand how images work, how we’re affected. Their understanding is pure behaviourism — humans have a black box for brains, so if you put something in, it comes out the other end. Morality is a simple question of conditioning and programming. How do you feel images work?

MS: Well, I think anything people say can work in individual cases. It may be that some crazed maniac can see something and decides to imitate. There seems to be a human demand for the depiction of violence. It’s not forced on people by the entertainment industry. In most cases, seeing this violence doesn’t cause it at all. The argument is that it’s cathartic, that it helps release aggression in a harmless way. In a fiction film, action is what’s of interest, and for action to move at all implies a certain violence which becomes a ballet in Hollywood films. Certain people could become inured to violence in real life by seeing this kind of film, but it probably happens so rarely it’s not necessarily a factor. I have a nine-year-old boy who really loves explosions. He makes beautiful drawings of them, of the ways different things come apart. And like all parents we worried about the gun thing, but he loves guns — finds guns, makes guns. I think he’s fairly safe; all his friends are into it too. The sexual part of it is also interesting but different. I think protests against sexual material are partly a projection of sexual fear. The word sex means “male and female,” and that leaves a lot of ways you can rub it and places to stick it [laughs] and this is part of the fantasy of it. I can get a hard-on looking at certain images. I like Penthouse sometimes: I find it quite stimulating, which is very interesting in terms of the realism of representation. I think it’s a good thing myself.

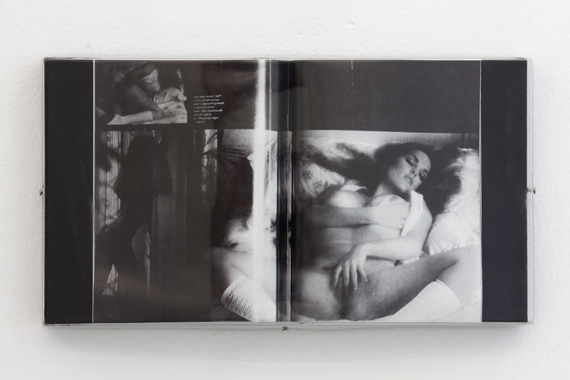

MH: Why don’t you work with more sexually explicit stuff?

MS: I have a lot. I did a photowork for the magazine Photo Communiqué. It uses one of those three- or four-page spreads they have in Penthouse showing a woman in various positions and settings, which I rephotographed in black-and-white. It’s illuminated so you can see the fold of the opening of the magazine. It was photographed on a table with the magazine spread open, and that’s important because that’s in the photographs too. You can see the spine and the curvature of the page itself which abstracts in a way, in a very beautiful way in some of them, into the image. It’s very sexy, but it’s also a transformation of the original material into something else which is this work, a magazine-reproduction photo-work.

MH: Why did you leave New York and come back to Toronto?

MS: There were several reasons. I always felt like a bit of a foreigner there. We were both involved in political activity around the Vietnam War and black power, and wondered if we shouldn’t be doing this back home. And we were starting to notice the danger — Joyce got attacked and escaped handily at her door once. It just seemed there was something old in New York, which is a strange thing to say. We started to see Canada as a place to make something new.

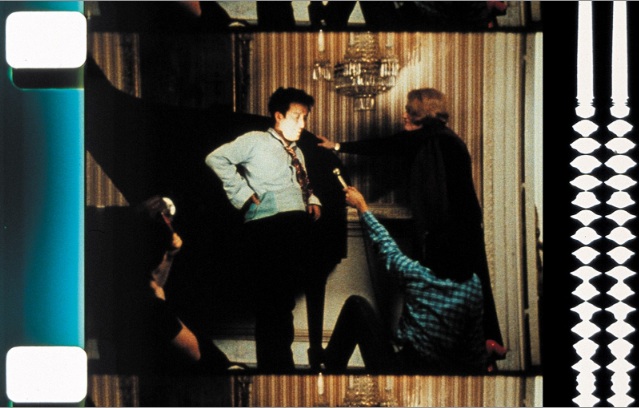

MH: This was the period when you were making Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx To Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen (4.5 hours 1974) — a film shot in both New York and Toronto. It’s an elaborate articulation of sound-image relations.

MS: Yes. Each scene uses a different cast and develops a relation between language and images of people. I wanted to foreground sound/image relations in the same way that I tried to foreground pans and zooms in previous work — to make them a living aspect of what’s going on. All of the film’s parts are very discrete, there’s really not that much connection. Eventually you can see that a language is developing, that the film itself speaks, and that this language articulates image/sound relations. The film is based on a sentence structure, where each scene is imagined as a word. Some words are long and take more time, while others are short. It’s like Lego in a way — you can arrange all these different things in different ways, but they each have their own individual significance, origin, and etymology. The film could be rearranged to make another sentence. The film features solos, duets, trios, quartets, quintets, sextets — it’s like an opera.

MH: Before you started shooting, was the entire film mapped out?

MS: No, I didn’t have all the sequences. I was incredibly obsessed by the whole thing, making notes all the time. There’s a water theme in the film, a cycle of what happens with water; as it evaporates it becomes clouds, rains, goes down to the seas and rivers, and comes back again. That cycle has been going on for millions of years. Probably no one else would ever notice it in the film. But it is there. For example, there’s a scene in an eighteenth century room where a woman tries to get Nam June Paik to sing “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall,” a Bob Dylan song. He tries and doesn’t get it right, and she doesn’t get it very right either. She plays him the “model,” the Dylan recording on camera with a cassette tape recorder. The song is a cultural thing — a cultural representation of rain. There are other references, then it does rain, visually and aurally in the log cabin scene. Then there’s a faucet in a sink which shows the civilized arrival of water, and then my tapping of the sink which is sink sound, and then it’s passing through our bodies into the system. Of course, when you see it, you don’t think that at all — it’s two people pissing. [laughs] Several women have called it a pissing contest, but I call it a piss duet. Water music. It was funny trying to get someone to do that. First of all, I thought someone who had been in a porn film would do it because they’re used to exposing themselves, and I made some phone calls to people who figured I was a piss freak. I tried to explain that I wasn’t interested in a sexual way; it doesn’t turn me on at all. It’s just that it would be interesting to see a man and a woman peeing together. After all, how often do you get to see someone pissing? So I had this guy who was my assistant at the time and he said, “Oh, I’ll do it,” and I asked this woman who was a dancer and she did it. I wanted to have lots of piss so we sat there drinking until one of them said, “I can’t stand it any longer.” [laughs]

MH: You had problems with the Censor Board with this film.

MS: Yes, there’s some fucking in it. Again, to speak as a formalist, the film is about intercourse, dialogue, exchange — what else could there be but that particular kind of exchange? I think they didn’t like the pissing either. I was going to show it at the Funnel and they said no, you can only show it at the Art Gallery of Ontario because these elevated people could take smut but these other people couldn’t. They would just go out and rape and kill.

MH: Tell me about Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) (15 min 1972-76).

MS: This is another thing I shot three times. I wasn’t totally satisfied with the first two takes and did it again. There’s a lot that’s accidental in it.

MH: Did they all feature a table with breakfast on it?

MS: Yes, though the things on the tabletop changed a bit in each shooting. I made this track with a heavy Plexiglas sheet on it about half-an-inch thick. We pushed this sheet along the top of the table, at right angles to the table, knocking over various things until it all gets smashed against the wall.

MH: So it’s a take on what happens when the camera zooms — it’s about optical compression.

MS: Yeah, it came up in a conversation with Hollis Frampton. I was just joking about making Wavelength as a tracking or trucking shot, and I immediately thought about a snowplow, which is how the camera functions in Breakfast — it plows its subject against the wall. In the same conversation we came up with this title Table Top Dolly — the expectations are some kind of table top dancer, dolly in the girly usage. I tried to arrange the objects so they would all fall into each other. I had milk which I wanted to spill, but in the first two they just didn’t do interesting things. I used the three takes shown consecutively to make a videotape called Three Breakfasts — it’s a series of variations. But the concept comes from literalizing the idea that photographing or filming makes the three-dimensional become two-dimensional.

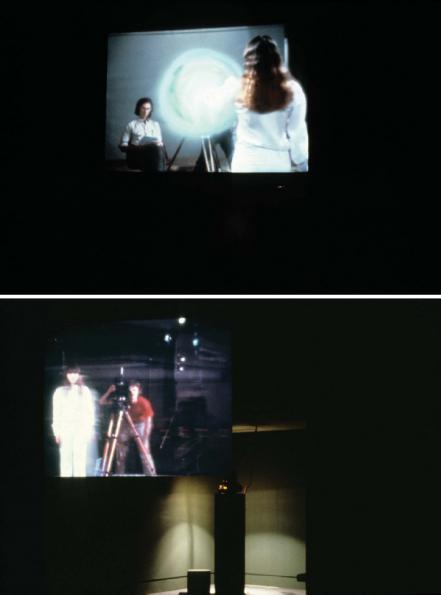

MH: Have you ever used film in a gallery context, as part of an installation?

MS: Only one called Two Sides to Every Story, which the National Gallery owns. It features two projectors on either side of a hanging metal screen so you can walk around it and see what’s on the other side. At one point the people who are acting in it go through the screen — they burst through it and come out to the other side, while at other times it’s a surface which they touch. The image is flat to the point of non-existence because light is not very thick, so when you’re in front of the screen the illusion of space seems to work as usual except that the screen is suspended. The normal situation is up against a wall, but in this case the image is not masked, which conventionally helps the illusion of depth. Here it’s an image floating in real space. The spectator can’t see both sides at once; you have to move around and see the image in new ways. I’ve also done several carousel slide pieces intended for galleries — you can just drop in on them. There’s one called Sink which came out of Wavelength, in a way.

There’s also one called Slidelength, which is even more closely related. At my Canal Street studio I had this really filthy sink, it had so much colour in it from paint residue and things I’d made but it was never cleaned out. I set the camera up in a fixed spot and affixed two lights and I used gels in front of the lamps to change the colour in every shot. It goes through a number of incredible transformations which has to do just with illumination because there’s no change other than that. Basically, it’s about mixing coloured light to make coloured light. The range of emotions that come from it is really quite extraordinary. Sometimes when the light was blue-green it kind of cleaned up the sink and it became transcendental in a way, like a Canova, a neo-classical sculpture. At the same time as I was working on this, Mark Rothko committed suicide. I heard about it after I’d finished shooting — he wasn’t all that far away from where I lived. He cut his wrists in a sink, and my sink had so much red in it, it was unbelievable. And the format of the image I made is a shape within a shape which is very close to Rothko. I always admired him. I never had any particular influence I could think of, but in this case I thought I wouldn’t have been able to see that soft rectangle set in a soft rectangle without his work. It was really very spooky. The slides are shown small, the size and height of a sink. Beside it stands a still photograph taken with so-called normal light, which acts as a kind of norm. One is constant and the other always changing.

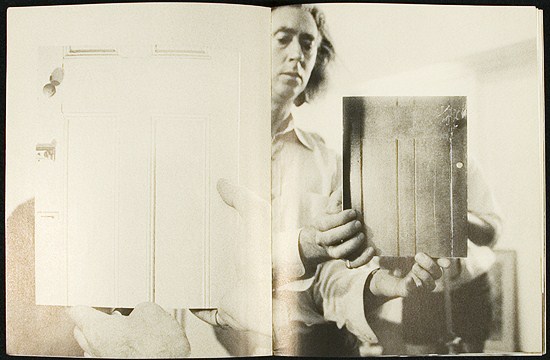

There’s also A Casing Shelved, which is best shown in auditoriums. I tried to make a gallery piece out of it but it didn’t work. It really needs the time; you have to be seated. It moves your eyes around in so many different ways. It’s an attempt to make a movie using the guidance of the voice. It’s a single slide accompanied by a voice saying, “Look at the top right hand corner, now look at the middle, now look at the bottom,” creating movement across the plane. I was working in the studio when I started looking at my shelf and thought it was interesting that all of the objects it held were art related — some of them were works but weren’t visible, parts of things I’d done, paint cans, etc. I thought it was a very interesting piece of sculpture that had been formed by chance, like lots of things, yet all for art related purposes. So I took the slide of it and made the tape just sitting in front of it, trying to describe it and the history of the objects there.

MH: Why make it a slide and not a movie?

MS: I like the frozen quality of slides and the Kodachrome colour was beautiful, and the idea of looking at a slide for so long was interesting. You never look at them that long. Basically, they’re for education or home stuff, and I guess even that’s become fairly rare. It has a beautiful kind of fixity to it. If it was on film, there’d be some fluttering — it would be another story, that’s for sure. In a new gallery piece called Recombinant I took a piece of plywood, cut out shapes and fit them back together leaving the saw cut spaced and exposed. It was painted white. This became the screen for slides to be projected against. Since it’s a surface that has its own objective existence, everything that’s projected on it has a relation to it. If you project on a flat, white surface, it’ll accept any space and your eye will read into it, but this is different. I made a set of eighty images that colour the screen. Every shot is a different spatial situation. Some are shot looking up so that when it’s projected you get this illusory feeling of seeing the ceiling, or looking down or sideways, and they all create a different space but always in dialogue, so to speak, with this surface.

MH: What was your starting point for Presents (90 min 1981)? I ask because there are two fairly separate sections which make up the film.

MS: Well, the first part is also divided into two. The opening of the film is about the molding of an image where it’s squeezed and stretched onto the screen. It starts with a line or slit that opens. Then it contracts to a small rectangle in the middle of the screen. Before that, you can see that it’s an image of a nude reclining woman, perhaps a still photo or a painting, and then in the small rectangle she gets up and, so to speak, looks back at you and then she lies down and then the picture stretches again to fill the frame. It was all done on video. The sound is an electronically produced chord done with computers — it’s a resolution of a chord in thirds and it twists itself in the same way as the image to resolve. It goes from a G-major chord to a C-major chord — a simple resolution — but it does so by twisting to a single note the same way the image does.

MH: Why this elaborate opening?

MS: It comes from a question: how can things be made? It turns out there are only three ways to make things physically. One way is molding — you have a material and you squeeze it into shape. Another way is to add something to something else. Another way is subtracting, taking parts away from an original whole. That’s how you make an object of any kind. Making things is part of the subject of the film. Making the film itself, but also the world that gets photographed including the set and its destruction. This making includes so-called destruction — when is destruction construction and when is it destruction? In order to have a two-by-four to build a house, you have to kill a tree, and so forth. There’s a lot of crisscrossing lines that produce a lot of different meanings. They’re chosen from a certain area, but they don’t say one specific thing. The first section shows molding and malleability — “when the maker makes the maker shapes,” but of course the fact that it’s an image of a naked woman is very important.

Thinking about Back and Forth, I had the idea it would be interesting to do a film by moving the set, making it do all the things that cameras ordinarily do. Rather than the camera dollying or trucking, the set would move and tilt; it attempts to truck forward by being lifted closer to the camera. I used a forklift to lift the entire set and move it closer to the camera. Before that happens, the woman lies in bed in a scene that recalls all the images of nude women from painting and Penthouse and stuff like that. (This is after the electronically moulded passage.) She’s still, and there’s no narrative implications because there’s a long hold which is very pictorial in the painting sense. And then there’s a knock and she gets up and puts on a dressing gown. She’s extremely beautiful — have you ever noticed that? Jane Fellowes is her name. She’s a model — it was important to the film that she’s a model. The film is called Presents because it’s about presentation — the word itself has extremely complicated usages. It’s often used in announcing films or plays or music. But it has a lot of other meanings. There are a lot of usages I tried to bring up in the film about presents — about presentation of the self and objects — and one that is quite pertinent is the zoological term, where females present themselves to males, that is, they lift their asses up. Naturally enough all mammals do it, although our forms of presentation are more complicated.

Someone comes to the door, and as she walks towards it, the set begins to move. In all my films, I’ve had the ambition to make the entire frame active, not only set a dominant figure against a background and, in this instance, the movement makes the entire set shiver and fall and the record player skips, and when the trucking ends the whole set lurches. The man enters and they search for something and find it. You can’t see what it is and it’s never named. Taking a cue from Breakfast, we made this huge modified wheelchair with a large plastic sheet in front of it and it drives into the set. It’s in front of the camera and it pushes things around and generally destroys the set. Then the camera pushes the wall down, which opens to a scene out the window which is a high rise building. And that’s the beginning of the new sequence. It’s done optically — it’s a matte shot — and the wall falls and reveals an exterior shot. From then on we see hundreds of shots which go further and further away from any immediate connection with the original scene — it’s a completely different mode. It’s all shot out in the world, it’s not staged, and it’s all hand-held pans. They are all little presents, little “nows.” They were shot all over the world because I wanted to go further away from the closed, staged interior of the beginning. It is like the opposite of Wavelength because it starts at a point and gets wider. For each cut there’s a drum beat — and that’s the only sound in this part of the film. It continues to discuss some of the implications of the first scene but now with images taken from “real life” because they’re documentary. Because it’s hand-held, it’s diaristic as well, and that’s one of the few times I’ve done that. It shows things that are intimate to me as well as things that are more public.

MH: Why pans?

MS: I think they’re more like glances than a hold is. It’s more normal to move with your hands and eyes than to hold them still — so it was my way of finding a formal use for hand-held camera which is different from other people’s. There are two kinds of making in cinema. One is totally staged, like in a historical drama where everything is constructed. The other is the construct of the physical filmstrip itself, the editing, which takes its most extreme form when you use images from real life, not images that are already formed by internal shaping, by being made, which is more like theatre.

MH: What do you mean “it’s at its most extreme”?

MS: When you record things that are outside in the world, you have no shaping capacity except in the way you take the image. If you make a scene, which I did in the first part, you make everything in the image. So these are really two extremes of construction, and I meant them to correlate to male and female, not necessarily to designate one specifically — but one of the themes of the film is how do these two parts of the same organism fit together? How do they relate to each other — male and female? Because the film’s made by a heterosexual man, it’s about my seeing women with a camera. And some of the women are very close to me. The biographical part of it was that I was breaking up with Joyce at the time and seeing Peggy. They’re both in it, as well as other women I know, and the film covers a range of activities done by women. For instance, there’s a woman cop. And the business of panning was very interesting because not only did I have to see something that I wanted to photograph, but I’d instantly have to see how the camera should move. If someone was walking, I’d pan with them. But sometimes I’d just follow a line on a building, or I’d draw contours, or I’d see that I could go from one point to another by moving through a third space. I shot for about a year, and it was terrific because I was always seeing that way. It was a bit like when I was making Rameau’s Nephew. I was always listening and thinking about language and making notes, but in this case I did it with the camera.

MH: How did you organize the material?

MS: Editing was really hard but interesting. I wanted to make every shot discrete, established by the preceding one by contrast. So if there was a horizontal pan in one shot, the next might have a vertical pan. If one shot was close-up, the next might be distant. There are so many elements in the shots there was no way I could totally classify everything, but I made lists. I also wanted connections to be made over long periods. There are two complementary events: one is an operation, and the other’s a caribou hunt in the Arctic. Both have a lot of blood and both are different kinds of cutting, you might say. [laughs] And they have their value and horror. In fact, film terminology is illustrated often in Presents. I edited these sequences out of order to give each section its own identity as a kind of now-but past experience which is what film is. Several people have said that the film is a commentary on Hollywood films — attempting to deconstruct them in a critical way. But that’s not true. I personally have no opposition to other cinemas. I think there are a lot of interesting things done. I watch Star Trek every night. I’m just trying to do something else, and in this case it happens to be staging, and staging happens to be an essential element in most narrative films.

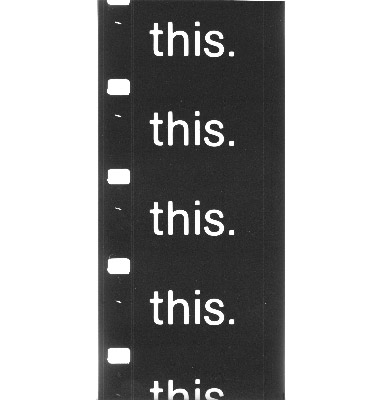

MH: So Is This (43 min silent 1982) seemed very timely in its release — interest in semiotics was running high, and your film takes language as its material, offering up a succession of individual words on the screen. But for all its theoretical interest, it has a very friendly, warm feeling.

MS: Which is strange because it’s just words; it’s a written text, but the style is conversational, as if you’re sort of blabbing to someone. I think it says that actually, “It’s just between you and me.” [laughs] I wrote the original text in 1975 with the idea of controlling the duration of words on a screen so it relates to One Second in Montreal.

MH: The film reaches a certain point and then repeats itself. Why?

MS: I think it says something like, there should be a résumé for people who have arrived late, so it goes back to the beginning. It says “Let’s look back” — and it is a real looking back; it’s a photographing of the projected film which isn’t the same as re-doing it, and it’s also a selective re-shooting because I single framed it. I was trying to catch most of the “this” words as I filmed, trying to make new arrangements. Again, it’s a theme and variation thing; a new elaboration of what’s already been stated.

MH: Tell me about the reference to the Censor Board.

MS: There’s a reference to the business with Rameau’s Nephew that happened just before that. The film claims not to be political, but it is. [laughs] It advises any children present to cover their eyes and then goes on to talk about the Censor Board.

MH: And the words “cock,” “tits,” “cunt,” that are flashed between other words?

MS: Those are interjected, subliminal. It’s like getting away with something. [laughs] There’s such a funny difference between seeing the word “cunt” or “cock” as opposed to the image. There’s a good joke about that later: “An orgy of reading.” [laughs]

MH: These things are only offensive insofar as we can name them; our language makes them obscene.

MS: I found a quote by Albert Einstein that was interesting. He was explaining to someone how he thinks. Interestingly enough, he doesn’t think as a mathematician. He sees things in terms of images or forces, and it’s only later that it becomes mathematical. Personally when I think about work, because my work is fairly conceptual, I don’t think of it so much verbally but in terms of mentally seeing the effect of doing something. It’s an image. But the fact remains that we name everything and that the organization of the world has to do with the recognition of something’s name. Saying “stool” has to do with its function, and I think one of the functions of the visual arts is to carry on some things that happen in the pre-verbal stages of everyone’s lives. Which again is something Brakhage is very conscious of. On the other hand, language is biological. I have a child and I’ve seen the arrival of language, and I’m convinced that in this species the brain is physiologically prepared at a certain time for naming, for language. It doesn’t matter what the language is, but the mechanisms for language begin to kick in. I don’t think it’s tragic that we’re trapped in language. I don’t think we could do what we’re doing without it. Language demonstrates its efficiency all the time. It works. Many people function totally verbally in that all they do is recognize that it’s a tool. But they don’t see it — because they haven’t been trained to see. And that’s one of the things the history of painting does for you; having seen the fantastic accomplishments of Monet, one can see light in a different way. It’s a shaping for seeing.

Something about Freud and Lacan that’s interesting is that to describe the pre-verbal period involves incredible sophistication by adults, and the more sophisticated the description, the further it is from the experience. Very young children can’t know anything about castration; they don’t even know there are balls. They know surfaces and anxiety related to sensual feelings. It’s all surfaces and touch in a continuity where there’s no fragmentation. Fragmentation itself is language. The only way to depict that period of a human being’s life would be to do it in terms of images. Or surfaces. It’s interesting that Lacan has sometimes resorted to diagrams, which are very obscure medieval things, and it seems that depiction might have to take a pictorial course to be anywhere near to precise in depicting events that are evanescent. I don’t think character is only formed by trauma, by particular critical events. I think it has more to do with repetition and translating and mis-translating the actions of your parents and your environment. Really silly mistakes can be made in translating a gesture that can shape your whole life. On the other hand, I think an organism is born as an entity that is very powerful, that’s already a person. And this entity can be hurt, warped, shaped in many ways, because it has no experience. But it has a structure, every person has a structure, and given more or less normal conditions this will include a great deal of anxiety and pain.

MH: There was a seven year break between So Is This and Seated Figures (42 min 1988). How come?

MS: I don’t know why. I’m always working on film in the sense that I’m thinking about it and writing notes. I’ve got ideas about bunches of things that never got done. Seated Figures returns to the idea of trying to make a film technique become a protagonist. Trucking covers space so I needed to cover a lot of terrain. La Region Centrale covered almost all the visible area that the camera could see but it was made from a central fixed location. So Seated Figures covers a lot of surfaces that starts with asphalt and ends with flowers in a field. It was done by making a gizmo on the back of my truck. I put the tripod and camera on it, pointed the camera at right angles to the ground, then I just chose all the various places. I wasn’t sure whether I would start at paradise and end at civilization or the reverse and finally ended up starting with the asphalt.

MH: You said somewhere that one of its subtexts was a history of roads.

MS: Yes, it goes from asphalt to gravel to sand then to more and more primitive paths. They happen to be lumber roads cutting ,through the woods, and on the way they go through puddles, then brooks and streams, and then the paths become grass, but wild grass (it’s not like a lawn or anything like that) and then the fields become filled with flowers.

MH: There’s a series of freeze frames that interrupt this flowing motion. Are these rest stops?

MS: I was hoping for the kind of reciprocal motion that happens in the cross in La Region Centrale. It was a still frame that contrasted with the incessant movement of the camera — like when you’re in a train yard you can’t tell whether you’re moving or the train beside you. The motion preceding the cross prompts a reaction, even though the cross is static. If the pan has been going down for a long time, then the cross might seem to rise. So it’s you that causes the motion instead of the image.

MH: Tell me about the soundtrack.

MS: The beginning is intended to be a couple of people at the projector; either it’s a booth or the projector’s in the room. Someone says, “Oh just a minute, I have to announce the film,” which they do and then the other guy says, “Do you want a coffee? How long is this film?” The sound after that is supposed to be the sound in a small viewing room. There’s a bit of an argument between a man and a woman who finally leave. And there’s a baby. In a very small way, the baby brings up that business of pre-verbal seeing. In the audience there’s someone that doesn’t see, or maybe they see like this all the time, or what is it that they see? Is it this?

MH: The last shot looks as if it’s been re-photographed from the screen. The image shows a field of flowers, and two hands clenched to form the shape of a bird drift past the picture.

MS: Yes, you can only do that when your hands are making shapes in the projection beam — if the audience was sitting in the theatre, they’ve now moved into the beam. It’s a way of getting the audience into the picture whereas before they’ve only been in the soundtrack.

MH: It’s a very traditional sort of ending: birds flying into the sunset.

MS: Yes, that’s right.

MH: Tell me about See You Later/Au Revoir (18 min 1990).

MS: A video studio in town got hold of a special slow motion camera and asked several people if they wanted to use it. The strange thing was that I’d had the idea for a long long time. I’d written about it from 1969 to 1970. I was thinking about making a slow motion film, again partly because of isolating techniques in the medium and using them. Before I shot Wavelength I took almost a year thinking about a slow zoom, but this one came like a vision. Immediately. I saw this guy at a desk, he gets up, puts his coat on, goes to the door and leaves. I got the call from the video studio a long time after the idea was written down and it seemed like time to try it. The camera only slowed to a third of its original speed, so I had to post-sync it down to the slowness I wanted. The video image is so manipulable, modifiable in a very hands-on way, we just tried different speeds. We dialed it down until we got to the slowest speed before it started to phase and that was it. I did the same with the sound, which is in sync.

MH: It seemed to me a meditation on mortality.

MS: A lot of people have said that — I didn’t think about that myself.

MH: The film shows an elongated farewell. It’s about getting older, slowing down, where every gesture is difficult and painful, all moving towards the end.

MS: I walk past a woman seated at a desk and people in the know know that the woman is Peggy — so I’m supposed to be saying good-bye to my wife. I keep mentioning Brakhage but there are other people. Brakhage liked it a lot. In fact, he was extremely moved by it. I was very surprised, but he ran up and embraced me and said, “It’s a last testament and it’s a farewell to your wife and it’s about death.” I never thought that. It’s a departure, that’s all. The Kine worked very well, and of course the colour in it is carefully staged — the man’s seated against green, then it goes through the spectrum to red which is on the door.

MH: Why the two titles?

MS: “See you later” is something you can do with film. It’s kind of a funny joke because you don’t want people to see it later, you want them to see it now, but that’s one of the possibilities of film. In terms of the original event they are seeing it later, but in a technological memory. The incident itself can’t be seen later; it was done. Also I say, “Good-bye,” and she says, “See you later,” but you can’t make that out because the voice is so slow. “Au revoir” means “see again” — it’s not just trying to be bilingual. Seeing a film is seeing the event later. And seeing it again.

MH: Tell me about To Lavoisier, Who Died in the Reign of Terror (53 min 1992).

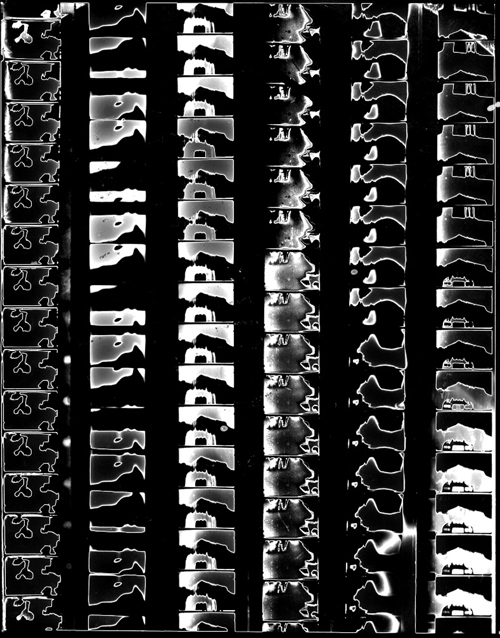

MS: It started with an accumulation of obscure rolls of film that date back to the sixties that, for some reason or other, I hadn’t shot. I realized that they had to be hand processed because no lab could do any of it now. I’d seen Carl Brown’s first film, Urban Fire, on a Canada Council jury and liked it and we met after that. Then he did Condensation of Sensation with sound by the CCMC — the music group I play in — and I really like that a lot. So I thought maybe Carl would like to work on this with me and do the processing and he was interested. We’d shoot maybe three or four versions of each scene on different stocks and talk about what approach he might take or he would just do whatever he felt like. One of the aspects of film is that it’s chemical. I wanted to work on the chemical thing partly because of video which has clarified film in a way — having an Other has foregrounded aspects of it. The film’s structure resembles a great big clock because the shot positions start from above and go around until you’re looking up and then they go back up to the top again. Every shot is a zoom so that after you’ve been watching the film for a while you might read the total shape as a spiral in space rather than a circle. The shape could also be felt as a going down and a coming back up, a fall and rise, which obviously could have many emotional effects. Here, it could be describing the guillotine.

When Carl does this kind of developing it eats into the entire image, but there are also many variations on the surface of the film independent of the image. In planning the shots, after the usual months of thinking about it, I chose to stage events which would be “ready,” so to speak, for a relationship between what was depicted and what the actual image looked like. The ping pong scene is a good example; it was reticulated, so that the ping pong ball often gets lost in the swarm of grain that is the image. The processing alters the original realism. I wanted the spectator to see the totality, the image, not just to see through its qualities to recognize the scene. For example, there’s a man eating, shot from above and you can see the plates are empty. But as an image the plates are not “empty,” they’re full of filmic matter. Same for the “empty” pot the woman in the kitchen holds up. “It” swarms. In one of the early shots a man waves, dodges, feints, amidst the chemically induced storm. In shooting it I asked him to pretend that there were mosquitoes or bees around him or things falling in the air like dust and to wave, slap them off, protect himself. In the end, he’s protecting himself from what happened to the emulsion. The bath scene uses a more liquid alteration of the image. She’s in the bath water as the real life event which is the subject of the shot. But as an image the effects of the liquid chemicals (also called a bath) submerge “her” too.

MH: Tell me about Lavoisier.

MS: Lavoisier is considered the father of modern chemistry. He made scientific what was previously alchemy. His classification of chemicals and their properties helped lead to photography. He was an amazing man who was killed by the new tax collectors despite his contributions to France, including agricultural improvements which helped the peasantry. I chose to show scenes of daily life, la vie quotidienne, not scenes of heroism or his great accomplishments. These scenes are altered by photography, chemistry, and the threat of fire. The way matter is transformed into a new state in photography is one of the themes of the film. The film is dedicated to him, but it’s not a biography.

MH: Why the inscription “To Lavoisier — who died in the reign of terror”? It gives the film an elegiac feeling.

MS: There are references to external danger in the sound and image, and the context of fire is that it is both useful and destructive. That reminds me of something Jonas Mekas said which was that a knife can cut your bread or stab someone in the heart. Well, fire can both cook your dinner and burn down your home. It has to be “domesticated” and understood. I think it functions beautifully as sound because it’s like a kind of random percussion which syncs with fortuitous events in the image. Even the silent parts of the film will someday have the sound of fire. As the optical track gets scratched, the clicks and scrapes and hissing is very close to fire sound.

MH: Because the film features such an aggressive assertion of purely filmic materials this elegy is also for film itself, for the passing of a chemical understanding.

MS: In a way it is. The transformation of a substance by fire is like the transformation of something by chemicals, which is a water or at least liquid thing. Fire and water are equivalent to fire’s two sides.

MH: Are you happy with the audience for experimental film?

MS: In some ways I can’t understand why experimental film continues to have such a small audience. I just think that it should be accessible to anyone who can see and think. And yet it’s not so. Sometimes I’ve attributed that to the training people get with narrative films — if they see something different they think that something’s wrong. According to McLuhanesque theories, people are more visual than literate now, so they might have a wider receptivity. Advertising and music videos have introduced other ways of organizing visual material than the narrative one, which might help. But how does distribution in theatres work? I thought, for instance, that La Region Centrale could be popular in the big movie sense. People take it sometimes as a science fiction film — after everyone’s dead there was a machine that did this. But that would depend on somebody taking it in hand and doing one of those million-dollar things that Hollywood does with a new movie — where there’s no escape from knowing at least that this film was made. But such a person or organization has never come along and maybe they never will. But I really don’t see that experimental films are obscure. Look at literature — our kinds of films are equivalent to poetry which has a tiny audience. Maybe that’s a similar field. But in literature people read a lot of different things, and yet people who have a film culture don’t know about this huge body of work which started with Lumière and Méliès which, after all, is experimental film. I just don’t understand their resistance.

MH: Some argue that MTV has shown the ability of the mainstream to absorb dissent — that it has managed to turn the aspirations of a generation of experimental filmmakers into record commercials.

MS: That was happening in New York in the sixties and seventies. Leslie Trumbull at the New York Filmmakers Coop told me there were a couple of advertising agencies that would rent ten or twenty films and use their ideas. I don’t see anything against that really; if they do use things there might be somebody who is clued into it that might see another use for it. Experimental films are so unavailable that someone can’t come across them by chance. You have to know about the area to see them. On the other hand, it’s surprising that it still exists, that there are young people coming to it. The medium itself still seems inviting and there’s still a lot to be done with it. And yet it’s going to die. Part of my life’s work is not only decaying, but soon there won’t be any way to show it.

Michael Snow Filmography

A to Z 7 min b/w silent 1956

New York Eye and Ear Control 34 min b/w 1964

Short Shave 4 min b/w 1965

Standard Time 8 min 1967

Wavelength 45 min 1967

Back and Forth 50 min 1969

One Second in Montreal 26 min b/w 1969

Dripping Water (with Joyce Wieland) 12 min b/w 1969

Side Seat Paintings Slides Sound Film 20 min 1970

La Region Centrale 180 min 1971

Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) 15 min silent 1972-76

Rameau’s Nephew By Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) By Wilma Schoen 4.5 hours 1974

Presents 90 min 1981

So Is This 43 min silent 1982

Seated Figures 41 min 1988

See You Later/Au Revoir 18 min 1990

To Lavoisier (Who Died in the Reign of Terror) 53 min 1992

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Michael Snow’s Seated Figures

Every beginning is arbitrary. I have noted in myself the emergence of the kind of attention I’m describing and called that a “beginning.” I’ll write more about that later… What’s interesting is not codifying experience but experiencing and understanding the nature of passages from one state to another without acknowledging “beginning” as having any more importance in the incident than “importance” has in this sentence. Or than “ending” in this…

(Michael Snow, “Passage,” Artforum Vol. X, no. 1, September 1971)

Michael Snow began making films in 1956 when he worked in the animation department at Graphics Film and used the equipment there to make his first film A to Z. Three films and thirteen years later he electrified the new American film scene with Wavelength, winner of the 1967 Knokke-le-Zout Festival in Belgium and Film Culture’s Ninth Independent Film Award. In Wavelength the camera traverses a New York loft using an intermittent zoom that closes some fourty-five minutes later upon a photograph mounted on the far wall. Every brick and board, once passed over, is left behind as the camera pushes on into the room, the frame itself marking the line between past and present, memory and anticipation. Wavelength seemed to me the first film I’d ever seen that required my attention-the story films that had gone before were already stuffed with answering looks and speeches, meanings which could only be followed. In Wavelength, on the other hand, there seemed to be no film without its audience; it lived in the same time we did, making us a gift of a present we would learn, or at least experience, together.

In my films I’ve tried to make something happen that couldn’t in any other way so there is something special about the experience that comes from the possibilities of the medium. If it seems worthwhile to make an art object at all which is sometimes questionable you’d better do something that adds to the world, not in a material sense but that as an experience has some distinction to it. At the same time the films are not coercive, they’re objective. The film is there and you are here. You’re equal. It’s neither fascism nor entertainment. (La Region Centrale by Michael Snow, Film Culture, no. 52, Spring 1971)

Wavelength was the first in a series of films that would take the camera as its subject. In Standard Time (1967) and Back and Forth (1968-69) he employed insistent camera pans and tilts to structure the film. In 1976 he made Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) where a sheer pane of plexiglass affixed to the camera slowly crushes its still life setting in a single, forward moving tracking shot—literalizing the notion of a flattened perspective. In 1971 he released the monumental La Region Centrale, a three and a half hour study of the Quebec wilderness for which the filmmaker designed a machine that allowed the camera to turn in every direction about its axis by remote control. Of the fourteen films Snow has made to date it is La Region Centrale that remains closest to his recently completed Seated Figures. In his 1969 proposal to the Canadian Film Development Corporation he wrote: