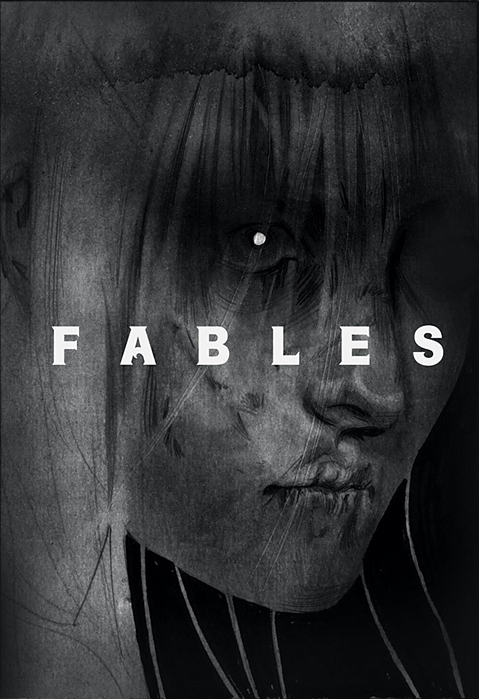

Anti-Sleekness Was Always My Weakness: an interview with Nadia Sistonen

While the super-8 camera was introduced as a consumer technology designed to stage the nuclear family, it has grown antiquated beneath the urgency of the electronic revolution. The VCR, camcorder, and home computer have become the primary sites of intercourse between multinational capital and its domestic constituents, imploding the site of the home as the frame of familial development. In the wake of the raster revolution, super-8 seemed one more arcane development, another passing footnote in technology’s tireless pursuit of the new. Yet even as its use as a medium for domestic exchange was waning, it found new cause in the hands of artists. Attracted by its low cost, anyone-can-do-it simplicity, groups of artists have used narrow gauge filmmaking as a means to democratize the machines of cinema, giving shape to alternative ideals of production, distribution, and exhibition.

In the past decade at least four cities have played host to narrow gauge interventions. In each instance it was taken up as a rallying point for a youthful generation caught in a recessionary cycle of rising prices and low income, haunted by the material dreams of a generation that left too little for its successors. In the late seventies, fuelled by drugs, punk rock, and a Lower East Side squalor that remained the final outraged witness to Manhattan’s spiraling real estate costs, a generation of no-wave filmers took up cameras in New York. Narrative by inclination and raw by necessity, these darkly drawn testaments of kitsch and cadavers retooled conventional genres into the home movies of a blank generation.

Toronto also enjoyed a boom in super-8 filmmaking in the late seventies. But while its roots may be similarly traced to a burgeoning punk rock movement, super-8 quickly congealed around an institutional setting. The Funnel was a renovated warehouse space in the city’s east end that would soon boast a hundred-seat theatre, offices, and equipment. A halfway house for the free spirited and socially misanthropic, the Funnel was host to the most difficult work on the planet while maintaining a democratic ideal of production—emblematized by its commitment to super-8. It remained for the decade before its collapse, the outpost of artist’s filmwork in Canada.

After the Funnel’s demise, super-8 activity went underground. But in a period of recession, which has left real estate prices high and jobs scarce, a new generation of makers have made super-8 their medium of choice. Not so much a group as a gaggle of scenesters, most have worked without the government support attached to many Canadian artists, nor have they associated themselves with the myriad groups, associations, co-ops, and collectives that form the Canadian artistic Imaginary. They have also opted out of the increasingly rigidified canonization of artist’s film work whose annual homage to old masters leaves little room or interest for new developments. In its place they have substituted a polyphony of exchange—from a women’s porn program to collaborations with radical groups in architecture, from safe sex advocacy to a lesbian/gay punk aesthetic published in xeroxed fanzines.

Nadia Sistonen is one of their number, a super-8 primitive bent on staging the private rituals of her sex. Often appearing in disguise, she returns the camera to its Latin roots as room or chamber, private quarters where the unthought and unspoken are lent expression. She invariably works alone, gathering the miniatures of her universe beneath the soliciting notice of the camera. Here she manages her transformations, adding layers of costume and paint in an archeology of memory that mines the body in a ritual of staging. Her changing appearance unfolds a range of selves that imagines the skin as the site of fantasy and projection. Here the skin is an organ of metamorphosis that defies its traditional attitudes of limit or threshold. Customarily the skin is where we stop and something else begins; it marks a perimeter of consciousness, a border that lends shape to an individual concern. Our body has become another way of saying ‘I,’ of asserting the finitude of thought and action.

But in staging a body at play with itself, Sistonen returns to a prelinguistic understanding, dissolving the boundaries of self and Other. Here the body is totemic, all touch and surface, and assumes aspects of its surround in a sympathetic attachment that beggars the divisions that language demands. If language is the harbinger of a fragmented consciousness, then Sistonen’s constructions exist at once before and after “in the beginning was the word.” Her return to childhood is unmarked by a longing to restore the primeval unity of innocence, to inhabit again a sentimentalized past where seeing and knowing are the same. Her return is not regressive, enacted as erasure and denial, but is undertaken as a remembering which dares to reveal a terrible secret: that mourning begins in infancy. Her rituals of loss feature a host of intensely fetishized objects, each teeming with life in the charged supernal space of Nadia’s playground. The teddy bear with the oversized dick, the convulsing elephant and the cock-eating tiger are all pressed into the service of a dramatic retelling, all players joined in a requiem of innocents. They owe their new-found animation to the artist who inhabits them; she invigorates their static recline in a gesture which crosses her own body with the bodies of her surround. They are the pallbearers for childhoods lost and found, their eroticized habits a sign of a premature understanding. The very young will teach us how to grieve.

The Bad Lady of Finland (5 minutes 1992) is an allegory of female want, a bawdy send up of ‘bad women’ and the desires they provoke. Sistonen assigns the bad lady a totemic animal—a crab, whose soft, edible flesh is guarded by a menacing shell and twin talons. An image of the crab opens Bad Lady, followed by a shot of the filmmaker in leopard-skin garb. Working with a pair of scissors, a mass of gold foil and a large glass scope, she gilds the crab, softening its appearance with the addition of tinsel. A pair of black and white shots through mottled glass follows, panning over a gaudily dressed woman writhing on a bed. She rubs her crotch with a pair of yellow Rubbermaid gloves, her face obliterated by a storm of overlaid scratches—as if she were protecting the identity of an accused. The scene shifts to another tableau of self-pleasure, a toque-capped couch lounger caresses what appears to be a massive hard-on, before she snips a hole in her underwear and reveals it to be a milk bottle. The crab makes a last appearance before the women returns, frolicking in the street. The leopard-skinned blonde follows, sucking again on the milk bottle before a shot of her buttocks fill the frame, overlaid with a stream of coloured markers.

Bad Lady‘s title recalls Sistonen’s Finnish origins, which she assumes in a procession of costume and masquerade. Her ‘danger’ appears in her ability to satisfy herself. There is no need for another here, yet this is just one more trope that Sistonen overturns in her milk bottle/masturbation scenario. Here the phallic woman converts her penis into mother’s milk, underlining the sensuality of both, seeking the origins of sex play in childhood. The film’s closing shot, a lone yellow bloom waving against a blank backdrop of concrete, depicts her sensual isolation in the face of rigidified sexual codes.

Fanny Perpendicular (3 minutes 1992) is a tale of domestic revenge. It begins with a hazy kitchen close-up of a woman making egg salad, while her cat looks on with hunger. A slow pan down her leg reveals the sign “You had your dinner”—and then a slide projection of a gun twitches over the cat before blood splashes onto a white wall. She ties the cat up, puts on her stockings and heels, and walks upstairs. Her face is carefully cropped out throughout, her identity marked instead by her actions, her preparations of food and dress displaying her transition from private to public space, which waits for her beyond the stairwell. The cat is her familiar, the trapped constituent of desire, a wordless longing on the rug, witness to her bloody fantasy. The murderous desires drawn by the gun are part of the private world she needs to put away before entering the world of others.

Anti-Sleekness Was Always My Weakness (6 minutes b/w 1991) narrates a succession of private rituals, converting a world of childhood play into erotic tableaux. It opens with the filmmaker bowing and kneeling before a makeshift altar—a Tender Vittles sign with twin bananas rising like horns on either side. Dressed in a black bra with mini skirt and black wig, Sistonen rises and falls in a distinctly sexual act as she embraces the spirit of worship. Switching from pixillated motion to real time adventure, she mashes a banana against her chest, then grabs a hammer and mashes the other one as well, rubbing it through her bra and nipples. In the next scene a small teddy bear with another banana rising between its legs is deep-throated by a small tiger hand-puppet. Sistonen soon replaces the puppet, caressing and licking the banana before taking a bite. On the soundtrack a soothing woman’s voice adds: “Mother came and caught her, and whipped her little daughter,” and then the sound of a baby crying. Sistonen reappears with Halloween-style make-up demarking bones on her chest, and smiles into the camera. These domestic reveries collect the small gestures of play in order to reinvent the body, splicing its comic masquerades, its panoply of identities, into a world of stuffed toys and make-believe which is soon charged with a forbidden eroticism.

The Gist of the Biscuit (5 minutes 1991) is a home-brewed psychodrama, which uses the kitchen table as an arena to stage the wounds of returning to childhood. After the title, scrawled on a rainy warehouse window, a brief still from The Cat In The Hat appears, a bright blue fish blowing ink into the cat’s eye, a small reminder of childhood’s casual cruelties. Over a rumbling and industrial discord a plaintive sax wails while a male voice intones “On the grey shores of time,” signalling this as a return, a revisitation of personal histories. On the table, a simple tableaux: a toy elephant lies prone while Sistonen manipulates a lipstick container in the foreground, winding its crimson tube up and down in a suggestive manner. As the film turns to colour, the filmmaker herself appears before the camera dressed like some postmodern sheriff with cowboy hat, glasses and toy lips. She holds a star in front of her eye and nods yes, a gesture aimed at granting reciprocal assent from her onlooker. A pan over an emptied make-up box follows, before the camera returns to the table. Now a trio of lipsticks lie on it, while the toy elephant jerks spasmodically in the foreground. After a dark and furtive colour passage, pliers appear trying to touch these lipsticks, to caress, but its steel teeth only manage to destroy them. In the film’s finale Sistonen rouges her vagina, converting it into a mouth, into which she inserts a cigarette and lights it.

Sistonen inhabits her child’s world with an adult’s understanding, endowing the relics of her past with a totemic sexuality. To this end she has taken up the super-8 camera to manufacture another kind of home movie. Its inexpensive, lightweight portability makes the camera another toy in Sistonen’s world of play, one more object rendered animate, another imaginary friend peopling the closeted space of her private dramas. Like a child setting dolls around a tea service and dramatizing their encounter, Sistonen dresses the stage with her camera, using the frame as an arena, typically drawing it close enough to the action so that it may be adjusted by herself. Far from an impassive observer, the camera is intimate, confidential, and imbued with an uncanny kind of presence. Invariably set upon a tripod, its fixed gaze entreats from its subject an uncommon bond, seeming to serve both as recorder and participant, objective and familiar. While frankly voyeuristic—Sistonen’s dramaturgy typically includes nudity, fellatio, smoking cunts, and the like—her use of the apparatus defuses its tendency towards objectification and spectacle. Refusing (so far) to make prints of her work, the projected image comes from the same strip of film that wound through the camera—arresting the obsessive reproduction of our electronic era, while attesting to the fragility and impermanence of her endeavour. Each projection runs the risk of scratching, burning, or breaking the film. Each is a performative gesture which reaffirms and underlines the body of the film even as it stages the body of its maker. For a filmer so concerned with articulating the relations between private and public, the context of her exhibition is equally important. Her filmwork does not exist as objects that may be plugged into existing outlets of dissemination; her work is listed in no distribution catalogue or managed by any dealer, save herself. Her screenings are word-of-mouth affairs—passed through a community of like-minded makers who are busily constructing a new space for artist’s film in the nineties. It is a scene in which frank independence from institutional support continues to swell a generation of makers and viewers gathered beneath the shape of things to come.

MH: Why do you work in super-8?

NS: It’s very accessible to me, and it’s very beautiful. I love its process — filming and going to the lab. I edit here at home on a hand-cranked viewer. I edit the original footage without a workprint.

MH: Are you against making prints?

NS: Oh no! I’d love to if I could! I don’t think anyone can make prints here in Toronto. Whenever I have to send my films away I just hope that nothing will happen.

MH: What if they were damaged or lost?

NS: I do transfer them to VHS. And hope for the best.

MH: What does it cost to make a film?

NS: A six or seven minute film costs $55. But it doesn’t feel like a small medium, or a less valuable medium.

MH: How much do you shoot compared to what you use?

NS: Maybe 70 percent. I try to shoot everything in order and edit in-camera.

MH: Is it hard getting it shown?

NS: No, I just take my projector if I have to. Screenings are organized and I submit something or get approached. Or you can organize one yourself.

MH: Are there a lot of people working in super-8?

NS: I know about ten personally, all here in Toronto.

MH: Do you see each other’s stuff and talk about it?

NS: Yes. We’re friends.

MH: Were you friends before making films?

NS: No. I came into this world two years ago and they were already there, some for two or three years, some longer — Linda Feesey, Marnie Parrell, Robert Kennedy, John Porter, Kika Thorne, Potemkin, Jonathan Pollard, Abattoir… I like doing everything on my own. It’s a necessity right now. Hopefully later I can collaborate.

MH: How many films have you made?

NS: About seven.

MH: Do you worry about that line between private and public? That you show too much, that sometimes you’re pushed to show more than you want, or that other times you show too little?

NS: No, I don’t worry about any of that. I have to let nature take its course the majority of the time. Maybe I do seem very vulnerable and open. But I feel that way all the time. So the films come out of where I am.

MH: Tell me about The Gist of the Biscuit (5 min 1991).

NS: The title means “the whole story,” “the big picture.” I think it’s a British phrase. Gist deals with the eroticism of cosmetics, especially lipstick.

MH: Do you think it projects the wrong image of you?

NS: No, it’s the right image, whatever that may be!

MH: Early on in the film there’s a long shot of an elephant toy.

NS: It has strings in its limbs which you can manipulate by putting your thumbs underneath it. The strings collapse and make it move. I had a few different ones when I was a kid.

MH: It lies on a table in the background, and in the foreground you hold a lipstick which is twisting up and down. Why are these objects together?

NS: Why not? I see “absurdities” everyday when I walk outside.

MH: What if it wasn’t an elephant, what if it was an umbrella?

NS: No, it had to be an elephant, something with a heart. That one in particular. I love elephants. But this wasn’t a serious elephant. It was blue and it had triangles painted on it. And I liked the way he moved.

MH: We see it move later on — what’s it doing?

NS: Going crazy, like orgasmic spasms. There’s three lipsticks on a table behind it. They’re like backup singers, like the chorus in a band. And then you don’t see him anymore. He does his stint and leaves. After the first shot I appear as a big business person, with a rich Texan hat and a star in my eye, trying to sell us on some idea. I have a little devil’s head in my mouth. Then we see some very dark shots of me applying lipstick. I just held a round mirror between my legs and filmed off the glass.

MH: Then you apply lipstick to your cunt, to turn it into a mouth, and smoke a cigarette out of it.

NS: It was for the comedy of it.

MH: The smoking shows a body at play with itself, inventing itself, showing itself…

NS: But not in a beautiful way — not glamorous. I’m tired of that way of seeing. I prefer a comical approach to the body, rather than all that “beauty” stuff.

MH: Your work unravels a traditional way of seeing by joining shots of different times and places, sometimes in colour or black and white, with completely different elements and styles.

NS: I just do what I have to do. That’s the way I see life. We can be sitting here talking, and over there, there’s a murder going on. I do have to keep it in check when I do the films — not to stray too far — but that’s just how I see it. I can’t really assume too much about things. For instance, if somebody drives into the storefront of Future’s Bakery with their car, someone might say, “Oh he’s drunk.” But I might say, maybe he had an epileptic fit, or maybe he was getting a blowjob from someone! It’s not good to always be that way; it’s not always a sane approach to being. But I have to allow a bit of that openness for myself. Sometimes I wish I could assume more. It would be so much easier.

MH: Why is that openness important?

NS: Maybe it lets you live fully. It’s just the way it is. I don’t always like it myself. It’s bothersome; it’s a royal pain in the posterior. I like it in the work but not in everyday living.

MH: When did you make Anti-Sleekness Was Always My Weakness (5 min b/w 1991)?

NS: That was done last summer, in 1991. It all happened on the spur of the moment. I had a couple of images in mind and other ideas kept coming.

MH: The film is composed of three shots which present fetishistic rituals that relate sex, costume, and play.

NS: It’s a comical look on rituals and erotica.

MH: Why blend those two?

NS: It’s part of our lives, and I don’t see why they shouldn’t go together. I’m moving in front of an altar that has these words on it — Tender Vittles — which is from a catfood box. I really like the way these words come together, Tender Vittles. It’s like a nice little gift that life can offer… my cats would agree.

MH: Why were you bowing towards it?

NS: Maybe because I’d like to give that. To remind people about tenderness.

MH: You take a hammer and push it over your breasts, and then a banana which you flatten on your chest with the hammer. Why these two things?

NS: I like the two opposite substances together — the hammer and the banana. A banana could be a tender vittle.

MH: Did you know you were going to do what you did?

NS: A little, but things always evolve.

MH: But you must have had a hammer around?

NS: Ten minutes before I started I did.

MH: Are you wearing a wig?

NS: Yes. I like its garish appeal. Everyone probably has more than one way of being, or a few beings within themselves. I know I have several.

MH: Is there someone specific that you become?

NS: No, it’s just a different feeling. It’s more playful, play acting. My boyfriend is a hairstylist, and he does some pretty wild things that enable you to get into a different character mode. One night he created an alien style, with shrimp-shaped hair that looked like a crown, like a queen from another place. It’s interesting to explore.

MH: Do you know Cindy Sherman’s stuff? She stages herself as these different people, and her photographs unfold a kaleidoscope of selves — I felt there was an element of that in your film. You’re also staging these small private scenes directly for the camera.

NS: Yes, I couldn’t do it with someone else; it would be too inhibiting. It’s like private playing. It’s been a very good thing for me to do. It’s absolutely changed my life and helped me. It helped me to feel that I could do something. I know about feeling worthless. I had a very hard time with that. I had lots of depression and then I came across this wondrous thing. I took a three week intensive filmmaking course at the Ontario College of Art in the summer of 1990. It was a complete benefit for my soul to get these things out that I had inside, to have an outlet. Ross McLaren taught it. It was the best thing I ever did. I just fell right into it. The films show strangers someone’s innermost goings on, and it’s very strange and exhilarating and exciting to get it out.

MH: Anti-Sleekness begins with you bobbing in front of this Tender Vittles altar as if trying to bring back the memory of a time by assuming its rhythm, to return the forgotten memories of the body to itself. These gestures seem to conjure the second half which shows a small stuffed bear with a banana sticking out of its crotch and you hold a tiger and show it going down on the banana. And then you go down on it and eat it.

NS: It could’ve been because I was hungry at that point. I’m always hungry. I wasn’t that conscious of these things when I was doing it.

MH: This is the second banana you destroy in the film; the first is mashed between your breasts. You think these are metaphors of castration?

NS: No, absolutely not. It’s a celebration of men and all that goes along with them.

MH: Tell me about the soundtrack.

NS: I took it from a radio show I listen to sometimes. It’s Psychic TV and Einsturzende Neubauten. I love the rhythmic passion. The first piece stops and you hear a dog barking. And then the mother says, “Whip the daughter.” I love that.

MH: And then we hear a girl moaning in sex, only her voice sounds through an aggressive percussive roar — so the implication of sexual abuse is clear.

NS: Yes, that’s true.

MH: She moans over pictures of these stuffed animals at play, these remnants of childhood which have been transformed through abuse. That they usually appear to us without genitals is a kind of sign of their innocence. But this is no longer possible. You return to these objects not in hopes of taking their genitals away, to restore them to some innocent time, but to redeem them sexually, to allow them to live in this new place.

NS: Yes, now they can go on. And then I return with autopsy scars on my torso. It’s a feeling of being reborn, which happens a lot if you let it out. You can always get something good out of something bad. That’s why I have a big smile on my face.

MH: I took it as a motif of transformation, that you’ve become another person now. Your face looked very masculine. And the ribs painted on you were like Halloween skeletons, the inside worn outside. It felt like an image of confession — that a secret is told and this new discovery is integrated again into life. So the skeleton is worn as a uniform of confession. Why didn’t you end the film after the Tender Vittles sequence?

NS: That wouldn’t be enough — there was/is so much more. The point is everything’s okay. That what one feels is all legitimate, real, and valuable.

MH: When you say that everything’s okay, it seems a reassurance, but also a reminder that everything used to be not okay.

NS: Yes, that’s right. It’s a constant struggle.

MH: Was the problem with pleasure?

NS: The problem was the whole kit and kaboodle.

Nadia Sistonen Filmography

Bliss Infection 3 minutes 1990

Anti-Sleekness Was Always My Weakness 6 minutes b/w 1991 (Sound: Psychic TV and Einsturzende Neubauten)

The Gist of the Biscuit 5 minutes b/w and colour 1991 (Sound: Trapezoid by Core)

Beheaded (for Exquisite Corpse Program of Pleasure Dome)

2.5 minutes 1992 (Sound: answering machine)

The Bad Lady of Finland 5 minutes 1992 (Sound: Thieves by Ministry and Hard Headed Woman and Don’t by Elvis Presley)

Fanny Perpendicular 3 minutes 1992 (Sound: I Saw the Light by Hank Williams Sr.)

Stayin’ Alive (for Period film group tribute to Saturday Night Fever) 3 minutes 1992 (Sound: Stayin’ Alive by the Bee Gees)

All films made in super-8

All films distributed by Nadia Sistonen