Notes on a talk by Michael Stone at Centre of Gravity, April 7, 2013

Please sit completely still so that the only thing that’s moving is your mind (and your fantasy life). We are sitting still for each other, we are leaning into each other’s stillness.

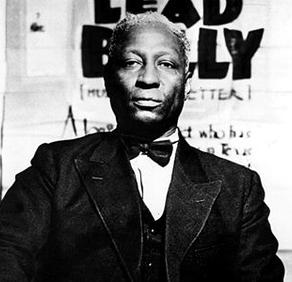

Lead Belly

I’d like to start in 1942 with the American blues musician Lead Belly. Huddie William Ledbetter (January 20, 1888 – December 6, 1949) was an iconic American folk and blues musician, and multi-instrumentalist, notable for his strong vocals, his virtuosity on the twelve-string guitar, and the songbook of folk standards he introduced. He spent a lot of his adult life in prison but his singing helped him with guards and governors. He wrote a song called Relax Your Mind.

Relax your mind

Ooh, it’ll make you live a great long time

Sometimes you’ve got to relax your mind.

When the light turns green

Ooh push down on your gasoline

One time you’ve got to relax your mind.

When the light turns red

Ooh, shove your breaks down to the bed,

One time you’ve got to relax your mind.

Tension

When you do sitting practice there’s a one-to-one relationship between tension and referring experience back to yourself. Sometimes while sitting thoughts drift into future possibilities or revive a past riff, and all those drifts are ways of forging a sense of self. And along with a sense of self, tension arises. Whenever you feel like a self there is an inevitable separation, a boundary, and this creates tension. This separation is what the Buddha called dukkha, which is often and unfortunately translated as suffering. Dukkha refers to the stress and strain that’s at the center of your heart when you can’t get out of yourself. Don Cupid, a British Christian theologian translates dukka as: bitter bitter sweet.

In sitting practice it’s necessary to work with the stress that arises, and in order to do this we need to sit still. Then you can see agitation in a clear way. Many yogis have a hard time sitting because they’re sensation addicts. On the cushion, we watch what happens with sensation. The first foundation of sitting practice is honesty. To honestly acknowledge what’s showing up in present experience. In the first ten minutes of sitting practice perhaps we could simply acknowledge what is showing up, not what you think is there, but what is there via sensations. To acknowledge is to respect it (even if it’s not good news). This also plays out in relationships. The first time you saw someone in a special way, it can be hard not to cling onto that view, and hold them to that standard, which is the special stress caused whenever the past lingers into the present. Some part of the present isn’t felt, it can’t emerge through the wrapping of the past, and this creates tension, or dukkha. You have to relax your mind.

Father

This is a good practice to do with your parents. Try to visualize your father before he was your father. Then contemplate what your father was like after you left the house. That way you can have a broader experience of the man, and not remain stuck inside the relative and conditioned portal of father-son relationships.

Mindfulness

For mindfulness to develop it requires: 1. Honesty. 2. Patience (to put in time with what is happening) 3. Softening. This may be the most important quality, but it only lives when the other two are working. When things get harder the breath should soften. The breath responds to the state of mind. The breath and the state of mind are like two fish swimming in tandem. It’s easier to be at war with yourself, to let the old loops play. To relax your mind changes the ecology of your body. What’s here warrants our attention. It’s too easy to be at war with ourselves.

Concentration

There’s an idea that concentration is a really intense practice. It’s being in the zone, it’s maximum effort all the time. But actually, in order to deepen concentration, you need to relax. Concentration isn’t a mental activity, it means being in touch, allowing yourself, opening yourself, to touch. To be in touch is to be in contact. Some try to concentrate by holding the mind. Holding the mind in one place is like getting on a bicycle and trying to be as still as you can. You need to shift as the terrain changes. Concentration is not fixed, it’s intimate – this brings deep stability.

Slide

You need a fluid movement, your attention is gliding with the breathing, you’re softening your attention until breath and attention are the same thing. It’s like going down a slide, you’re right with the breath, with every inhale and exhale. That’s like going down the slide. But then you have a thought, and you have to go climb up the ladder again. Finding the ladder again and again, the return to the ladder – this is what we call mindfulness. You stay with the breath, then you come out of it, then you start over. Starting over is the practice. Getting back up the ladder is the practice.

Slide on the breath. Don’t try and hold the mind still. Slide for as long as you can catch the ride. Then get on it again. Then the mind softens into it. Fixating the mind creates stress and strain. We have enough strain already. Try and extend the glide. How long can you glide for? Part of the glide is to let go. Relax your mind.

Shantideva

We’ve been studying an 8th century Indian text called A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life by Shantideva. Standing behind everything Shantideva says about practice is that we are working to create Bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is the passion to awaken. Bodhicitta is an attitude of wanting to live with clarity to benefit all beings. It’s rare to cultivate this attitude. This book offers a course in how to make clarity a centerpiece of your life (instead of, for instance, shopping, though shopping offers the possibility of being better dressed). The first chapter is about how wonderful bodhicitta is. The second chapter asks us to see where we’ve been unskillful and atone. Forgiveness arrives at the beginning of the path. We need to forgive others and forgive ourselves. The third chapter: once you’ve practiced forgiveness you can cultivate charity. A commitment to the path. The fourth chapter is about developing a discriminating awareness to see what stops you from connecting with clarity. The fifth chapter is conscientiousness: how to have the attitude of going forward in your practice. The sixth chapter is patience. It’s common to be frustrated and angry because of our setbacks. How to sit with frustration? The seventh chapter is virya. Virya is a strong, continuous, joyful effort that underpins practice.

Having patience, I should develop enthusiasm;

For Awakening will dwell only in those who exert themselves.

Just as there is no movement without wind,

So merit does not occur without enthusiasm.

What is enthusiasm? It is finding joy in what is wholesome.

Its opposing factors are explained

As laziness, attraction to what is harmful

And despising oneself out of despondency.

Because of attachment to the pleasurable taste of idleness,

Because of craving for sleep

And because of having no disillusion with the misery of cyclical existence,

Laziness grows very strong.

Whole

Enthusiasm is finding joy in what is wholesome. In the whole. Its opposing factors are laziness and an attraction to what is harmful. Whenever there is openness the energies of being closed draw near, opening and closing are very close too each other, like lovers hoping to kiss. The opposing factors to enthusiasm are laziness and not thinking highly enough about our potential. On the other side of enthusiasm, the kissing cousin, is laziness. That’s why Shantideva wants to talk about enthusiasm, but spends so much time talking about laziness.

When we are lazy we don’t think about the real nature of our lives. The antidote to laziness is to raise our energy through “appropriate clarity.” About what our life is for. Another motivating factor is death. If you are asleep “it’s like being a buffalo in a butcher shop.” To be close to death and not have clarity is like being a buffalo in a butcher shop. How can I not get my act together?

Nevertheless, it frightens me to think

That I may have to give away my arms and legs

Without discriminating between what is heavy and what is light,

I am reduced to fear through confusion.

Renunciation

There was a student of Robert Aitken who wanted to be a full time practitioner. The family insisted that she get married instead. One day she came to see him. She had cut off her ring finger. She told him, “The only thing I want to be married to is the dharma.” It frightens me to think of what I have to give up to practice, if I’m really going to live a life of clarity. I might have to give up my house, or the job I have that hurts others.

A student once came to Shunryu Suzuki and asked him about what he would have to give up to practice. He asked, “If I go deep into practice, do I have to give up the will to live?” Suzuki said, “Yes, but without gaining the will to die.”

Prevent/Promote

How to prevent unhealthy states (abandon old roads). Prevent and abandon.

How to promote healthy states of mind (strengthen them). Promote and strengthen.

You could ask yourself: how are you keeping your mind relaxed right now? 1. Enthusiasm (modifying energy), 2. Relaxation. Relaxing the mind allows us to be appropriate.

Exercise

Try this partner practice. Sit face to face. Each person takes turns, five minutes each. The first person asks, “How are you lazy?” The second person answers. The first person says, “Thank you. What do you really want?” The second person answers. Repeat for five minutes. Answer as quickly as you can, let the words flow.

A monk asked another monk while he weighing flax. “What is the Buddha?” The monk (as he was looking at the scale): three pounds of flax.