Death Dances On: The films of Peter Dudar

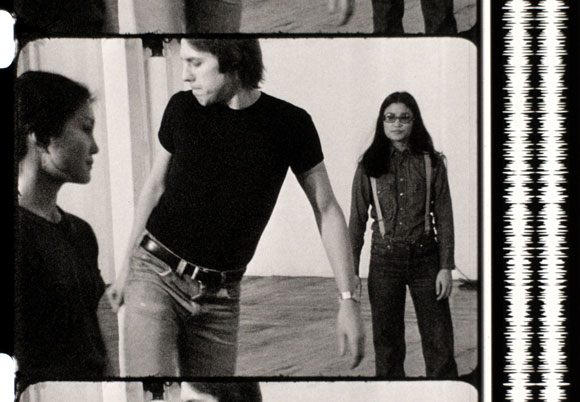

Peter Dudar is a longtime member of the Toronto arts community. He began his interdisciplinary work with Lily Eng under the name “Missing Associates” in 1972, participating in the first Canadian Performance Art Tour of Europe in the same year and following it with numerous performances around the world. During the ten years of their collaboration, Eng and Dudar’s performances moved from an examination of movement to an increasing concern with narrative framing, storytelling and history. While Eng was primarily a dancer, Dudar’s initial contributions prescribed movements/situations in which the performers would be expected to improvise dialogue. These Cage-inspired gestures of composition gave way in the ensuing years to a join between socialist movements and the movements of the body, an ideological revolution embodied in the gestures of dance. By the mid-seventies, Eng and Dudar were heavily involved with CEAC, the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication, an intermedia organization which forged important links to conceptual art/left wing groups in Europe and North America. As part of Dudar/Eng’s move towards an increasingly politicized performance context, film and video became increasingly important, working alternately to re-frame the live experience of the dance or to introduce new elements. While Dudar’s film work was initially deployed within these performances, nine films remain today as a record of this period, as well as being fully accomplished works in their own right. These nine films made between 1974 and 1979 draft a line from structuralism to narrative, from silence to sound, focusing throughout on the movement of the human form through space.

Running in 0 and R (1976) features Dudar and Eng running along the perimeters of a room whose “fourth wall” is the camera itself. Attired in plain, proletarian garb, they are photographed in sync sound in a grainy black and white, their circling jog prefiguring the revolutionary concerns of their later work. This over-lapping race is part cinema verité, part performance document and part reflection on the turning loops of cinema itself. Photographed in five distinct sections, each broken by a handclapped sync mark at the head, the camera moves from a long static shot to a laterally panning close-up, and returns to the long static shot before closing again in a laterally panning close-up.

The pans direct our attention which imperceptibly slips from one runner to the other, while the closer shots (3 and 5) give an abstraction to the moving forms which the long shots have grounded in full space. It is a movement from theatre to film. (Dance and Film, Art Gallery of Ontario)

Unabashedly structural, Crash Points (1977) shows two dancers running laps in a closed room whose very containment and isolation are a metaphor for the structural enterprise. Raised, horizontal steel rods are repeatedly toppled to signal shifts in the direction of the two runners. The camera entertains six successive strategies/positions in showing the ‘dance’, each prefaced by Lily Eng’s stern enumeration of roll and take. Even as these simple circuits emblematize the shape of desire, the dancers’ mis-takes and increasing fatigue ensure that repetition is a form of change, that while the general precepts of the dance are fixed, each moment is different from the next.

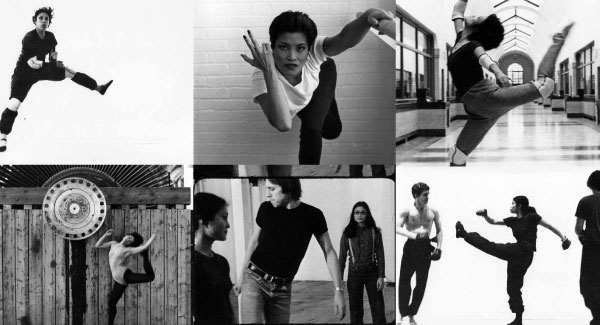

The Dogs of Dance (1977) opens with a text by Martha Graham, “Movement is the most powerful and dangerous art medium known.” A successive laying on of texts ensues. First, a photograph depicts an oriental woman determinedly straining at an off-screen figure; then a long typewritten account is laid overtop. It describes an encounter between a Chinese lord and a rebellious band. In his insistent conflation of dancers and warriors, Dudar remarks the body as a site of political struggle, its every gesture an ideological one. He’s not simply crossing the room, he’s showing how state control lies inside the body. The film’s title The Dogs of Dance rewrites the title of Frederic Forsythe’s mercenary bestseller, The Dogs of War, even as Dudar rewrites Asian warrior tracts, substituting the word “dancer” for the word “warrior.” It is now the dancer that must prepare for death and combat repressive regimes because the gestures of art are the gestures of opposition, and this opposition must lead to war. Three broadly allegorical ‘dance’ scenes follow, each interrupted by a sequence of intertitles, each depicting a series of figures engaged in martial arts combat. Lensed once again in a studio setting, these gymnastic enclosures are reframed by a revolutionary text that ironically insists on the importance of action over words. Photographed in real time, without dialogue, a trio of martial arts boxers engages in simulated sparring that slips insistently into reality as unexpected blows draw blood. These ‘slips’ blur the line between dancing and fighting, between art and life, and between the model of reality and the reality of the model.

Over the course of these nine early films, Dudar’s camera is rooted to the spot. This single vantage mimes the fixed point of view of their performance audience, while Dudar’s studio interiors, unchanged lighting and interest in real time, synchronous sound recording, likewise restage performance concerns. The content of these nine films is the issue of a radical reduction. Typically, everyday movements are performed by a small cast in a nondescript space. This space is typically imaged as a closed and unchanging arena. Both the geography and the movements that inhabit these films are closed systems, recalling the controlled conditions of a scientific experiment. What finally breaks the looping, structuralist round dance of his early work is the introduction of the word in The Dogs of Dance. Photographed, like the performance, in long unbroken takes, Dudar lays one text over another in a sedimentary fashion that introduces new information as a continual amendment of the old. These overlapping layers of meaning work to produce a non-linear text that must be read associatively, as simultaneous and fragmented histories that are left for the viewer to assemble. This mutual displacement of body and language led Dudar to begin a different kind of research for his new work, one which would begin with the historical movement of bodies subject now not to the constraints of a theoretical structuralism, but to a changing political wind. In 1980 he began interviewing a series of people who had survived World War Two. Using the transcription of these tapes, he worked with Lily Eng to stage performances mixing history, myth, dance and intertitles. These would be powerfully integrated into a film entitled DP (1981).

Walter Benjamin wrote that there are two kinds of storytellers. The first, having lived their entire life in a single location, are privy to the myths, legends and history of their surround. The second, wandering from one place to the next, brings the stories of one region to another. In DP, Dudar himself appears as the storyteller, yet his narration falls between the two. His protagonist is neither Russian nor German, Allied nor Axis. Born a Ukrainian, his country is occupied first by the Russians, and subsequently by the Germans. Made to choose between joining the German army, working as forced labour or death, he volunteers to work in the German factories. After a brutal mid-winter, open-air train ride, he arrives in Germany to work twelve hour days on starvation rations. After the workers petition their German rulers for more rations, they are dispatched to the concentration camps. A year later he is released, and works on a private German farm. Shortly afterwards the war ends, but he finds himself in a zone signed over to the Russians by the Allied powers at the Yalta Conference. Facing certain death at the hands of the Russians, he decides to walk to America, crossing borders in a starvation trek that lands him finally in a camp for displaced persons (DP). His closing speech details the fates of those left behind, slaughtered in a nameless struggle both sides of the war claim someone else is responsible for. Dudar’s narrative relates the forced travel of a man for whom no country is home, and for whom allegiance is a question of survival, not ideology. Whether as anti-Russian resistance worker in his native Ukraine, forced labourer/death camp prisoner in Germany, or ready to risk all in an attempt to gain the security of the Allied occupation (a power he despised and mistrusted as much as the Russians), he is in a state of perpetual exile. Breaking from the confines of a death-inspired culture, his aim of survival is finally directed towards the act of representation itself, bearing witness to horrors too inhuman to imagine, save for those who were made to endure them.

As soon after liberation as Yehuda Baka was strong enough to “hold a pencil in my hand, ” he made a series of drawings of everything he could remember of the gas chambers, the dressing rooms and the crematoria at Birkenau: the things he had seen, and the things he had asked the Jews of the Sonderkommando to describe to him, so that if he survived he could record it. “/ asked the Sonderkommando to tell me,” he later explained, “so that if one day I came out / will tell the world.” (The Holocaust by Martin Gilbert)

But the telling of these stories follows an uneasy recollection, related in a tragic and extreme circumstance that beggars simple understanding. Even as he speaks, enormous “X”s appear over the image of the filmmaker, putting his speech under the sign of erasure, while a fragmented montage and intertitles elide any verité notions of real time documentary ‘truth.’ His insistence that, “You can’t possibly understand how it was,” is an irreconcilable paradox. If it is conceded, then we cannot know or understand the story he is telling us. If it is false, then his story, or some part of it, may be false as well. In place of the seamless narrative closure afforded by reliable eyewitnesses and corroborated by historical evidence, Dudar stages this story as a mock interrogation, an offscreen voice raising intermittent questions put to his patently acted persona. He appears in a series of poses behind uniformly coloured backdrops. The brilliantly coloured titles that interrupt and underscore his speech likewise add to the foregrounding of artifice, a pointed reminder of DP‘s status as staged document. Perhaps memory and history are always stagings of the present.

Dudar’s ‘alienation’ techniques show his speech as a subjectivity under intense historical pressure, a construction site. DP is arranged across three lines of development. The first features the filmmaker himself, recounting the purportedly documentary circumstance of his own life. The second strand is held by Lily Eng, a dancer moving through the hallways of a vast institution. Even as Dudar speaks of the inhuman conditions in the factory, Eng stabs her fist into her face, spins sneakers across the floor or sputters angry phonemes into the camera. The third line shows the printing of two photographs – the first an image of the narrator/filmmaker as a guard in the DP camp, the second an image of a baby. This child later appears crawling into the same institutional hallways as the dancer, gazing in wonder at the camera. Later on, marker in hand, the child scribbles over its own photograph, but without effect: the ink has already dried. This child is clearly figured as the ‘effect’ of a history which is given shape by its means of communication. The child’s dry markers suggest that some forms of re-membering are impervious to the remarks of others.

Three years later, Dudar unwrapped his last completed film to date, entitled Transylvania 1917 (1985). Owing in part to the twenty year silence which has ensued, it is tempting to view Transylvania as a summary work, the culmination of a decade’s expression in film, dance and performance. While the use of dance, isolated protagonists speaking in tableaux settings, and the narratives of war are familiar from his earlier work, Transylvania’s aggressively synthetic montage and impassioned style mark it as a bold and impressive new work. Its strategies of historical simulation are well rehearsed in the Canadian avant garde, most notably in the films of women filmmakers like Patricia Gruben, Martha Davis, Veronika Soul and Ann Marie Fleming. Many of these filmmakers have begun with ‘travelogues’ that have been restaged using patently non-realistic models. All have worked to produce an equivalence between past and present, focusing these ‘new’ narratives on the process of memory itself, on the acts of framing, selection and perspective.

Oscar Wilde wrote that actions were the first tragedy of our lives, words the second, and Dudar shuttles between the two with a convincing ease in Transylvania 1917. It relates the story of Denes, the eldest son of a Transylvanian family forced into a slave-like apprenticeship to an interior designer. He joins the Union, becomes a Marxist and hopes to join the Communist Party. After his return home to attend to his dying father, war is declared, and he is drafted into the Hungarian army. At Lemberg, on the Russian front, in the late August 1914, he is shot and left for dead. He is found by Russians who are Jewish like himself, and moves through a series of state hospitals trying to recover from his punctured lung.

Denes and I became friends at the asylum. We shared political interests, but arrived by different means. I took a reconnaissance patrol into the forest and walked into a Russian patrol right at the crossroads. Then I did the logical thing, I surrendered. But the Russian sergeant demanded that he surrender, even though his patrol outnumbered us two to one. I didn’t want to argue all night, so I led the Russians back to our camp. My commander wanted to know how I’d overcome a superior force without a single casualty. I told him the enemy figured we were either the advance for the whole regiment, or just nuts, so they surrendered. I got a silver medal. First chance I got, I surrendered again. (from Transylvania 1917 by Peter Dudar)

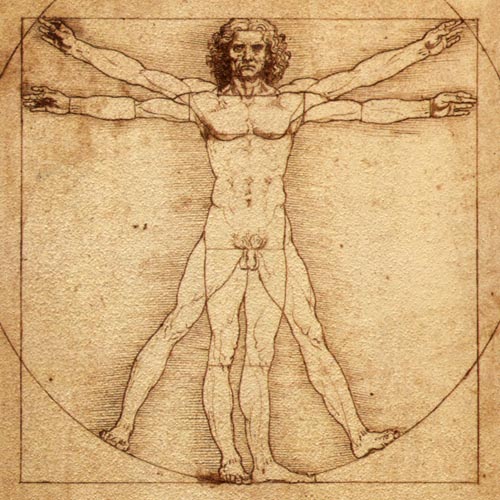

Caught in a system of representation which poses a static interpretation of the universe from the divine right of emperors, to a class system, to a perfect physical form, Denes’s confrontations with the turbulence of Eastern Europe’s political situation becomes the territory of a no man’s land, where superstition counteracts the conflicts of ideology.” (“Peter Dudar/Adrienne Mitchell” by Dot Tuer, Vanguard, March, 1985)

Da Vinci’s Vetruvian man is a recurring motif throughout Transylvania. His naked, outstretched limbs cast the body as a measure and model of the universe. But using a series of flip book overlays, Dudar transforms this Renaissance ideal into a series of mythological beasts. Elephant heads, horse hooves and wolf tails rapidly dissemble the unifying vision of the past. This beastly preoccupation is rhymed in a series of texts that run paralIel to Denes’s tale, slowing the advance of his story to include a preoccupation with the animal world. Laid between the ravages of war and revolution, this wild kingdom of mythological monsters, nightmare dread and insect fascination, joins the bloodied warriors of Europe with the animals in their midst. Dudar crosses animal and human until they merge in a vanishing point at the film’s horizon, in “no man’s land.” Da Vinci’s sketch fairly shimmers with the instrumental reason whose passion for utility has removed us from our ecological trappings. But the animal signatures that run the course of Transylvania remind us that we have not come so far after all, that the shape of our bodies is also animal, that they are also our ancestors.

Recovered at last from his punctured lung, Denes boards a train to the front. In the Don Province the train stops for Russian inspection, and he fears their search will uncover the Hungarian uniform he wears beneath civilian clothes. As they draw nearer, a savage dog attacks one of the soldiers who are forced to shoot him. They wave the train on and Denes disembarks the day before Christmas, twenty kilometres from the front, thirty degrees below zero. The next day he makes his way into the trenches wearing a Russian uniform. Most of the men are sleeping. The air is quiet. Suddenly, he leaps from the trench and bolts to the German side. Listening for the sound of gunfire he tears the Russian uniform away to reveal his Hungarian uniform. Before him, an immense thicket of barbed wire rises skywards. He reaches towards the wire, feeling his feet leave the ground as if he were flying. In his mind, the patent refrain from the film’s opening plays on, “Ideology is not acquired by thought but by breathing haunted air.”

Peter Dudar Films

Walking Away (1974, 16mm,colour, Silent, 1 min.)

Two Passersby On Foot (1975, 16mm, b/w, silent, 28 min.)

Running in O and R (1975, 16mm, b/w, sound, 20 min.)

Editing on the Run (1976, 16mm, colour, [sound), 26 min.)

Crash Points (1976, 16mm, b/w, [sound), 19 min.)

Crash Points 2 (1977, 16mm, b/w, [sound], 11 min.)

Penetrated (1977, 16mm, colour, [sound], 13.5 min.)

Two Deadly Women (1978,16mm, colour, [sound) 15 min.)

The Dogs of Dance (1979, 16mm, colour, sound, 19 min.)

DP (1982, 16mm, colour, sound, 17 min.)

Transylvania 1917 (1985, 16mm, colour, sound, 30 min.)

Originally published in Independent Eye, Fall 1990.