- Anarchy and Institutions (pdf)

- Colour Separation (pdf)

Peter Lipskis: I Was a Teenage Personality Crisis! (an interview) (1991)

Peter Lipskis is the mad hobbyist of the Canadian fringe. Fast cars, teen flicks and early colour processes have all shuddered past his wandering attention. He has worked for two decades, producing twenty-one short films and a handful of videos. Across Canada there are fewer than a dozen who have been occupied with the task of artist’s filmwork for as long — none have been as prolifically obscure as Lipskis, nor could any boast his range of expression. Taken as a whole, his oeuvre displays frank contradictions and shifts in interest, alongside enormous thematic and qualitative differences. He began with the feeling that we live in a time already too filled with images, and devised a series of mathematical systems into which “found footage” could be incorporated. Lifting shots out of prison dramas, dating films and sports documentaries he hurled them back onto the screen in delirous spasms of disarray, asking that we look again at the world we are busily reproducing. Spare Parts (1976), Processed Gello (1977), and It’s A Mixed Up World (1982) were all produced in this fashion. When Lipskis has taken up the camera, it has often been to produce images of his own life and travels, as in the cross-America Trance America Impressions (1977), his devastating family portrait Home Movie (1977) or the touching Dance Masks: The World of Margaret Severn (1981). In the early eighties, the chilling alarm archivists had long sounded finally hit home: much of our motion picture heritage was being lost. While Hollywood scrambled to restore early classics, Lipskis devoted himself to a study of early colour processes, producing a quartet of hallucinogenic documentaries. No mention of Lipskis’s prolific output would be complete without mentioning his love of the automobile. In The Red Car (1985), GT86 (1986), GT88 (1988), The Green Flag (1988) and On and Off the Road (1991) he celebrates a mechanical universe, where the merely human has been replaced by a transcendent technology. A passionate model builder as a child, each of his movies offer up worlds in miniature, turning in an orbit some have learned to call home.

PL: My interest in film began around 1970 while listening to records. For me, sound came first and the image followed. Pictures arrived with consciousness-altering drugs and rock concert light shows — these were formative experiences that some of my work has replayed. My first film was called Julia Dream (3 min super-8 1973) after the song by Pink Floyd. I timed the music, wrote out the lyrics, made a storyboard, and began shooting. It opens and closes with an old man dreaming on a parkbench — though at the end of the film only his coat remains. In between we see his dream which shows a white-robed woman who wanders through a number of pastoral settings and ends up in a cemetery. The film suggests a connection between love and death. In 1973, I travelled to Europe to visit the sites of classical culture. I was very inspired by this work and wanted to continue in that tradition, I felt a strong connection to antiquity. These small gestures that have survived the loss of their political ideals, the changes brought over centuries — they’ve assumed a weight over time, and you can’t help seeing at them without the feeling that they will endure long after you’re gone. I decided to study art and enrolled at the University of British Columbia where David Rimmer happened to begin his first year teaching. I also attended Al Razutis’s first teaching job — in 1974 the Vancouver School of Art (later Emily Carr) offered a three week multi-media course taught by Al. This was very influential for me. Al was using films, subjecting them to video feedback, filming the results off a monitor, then taking them onto the optical printer. So from the beginning I was interested in film and video, I never understood the separation other artists demanded between the two. Al had built his own optical printer which we could use there, and he was into holography and ancient Egypt. It was all very mysterious and mystical.

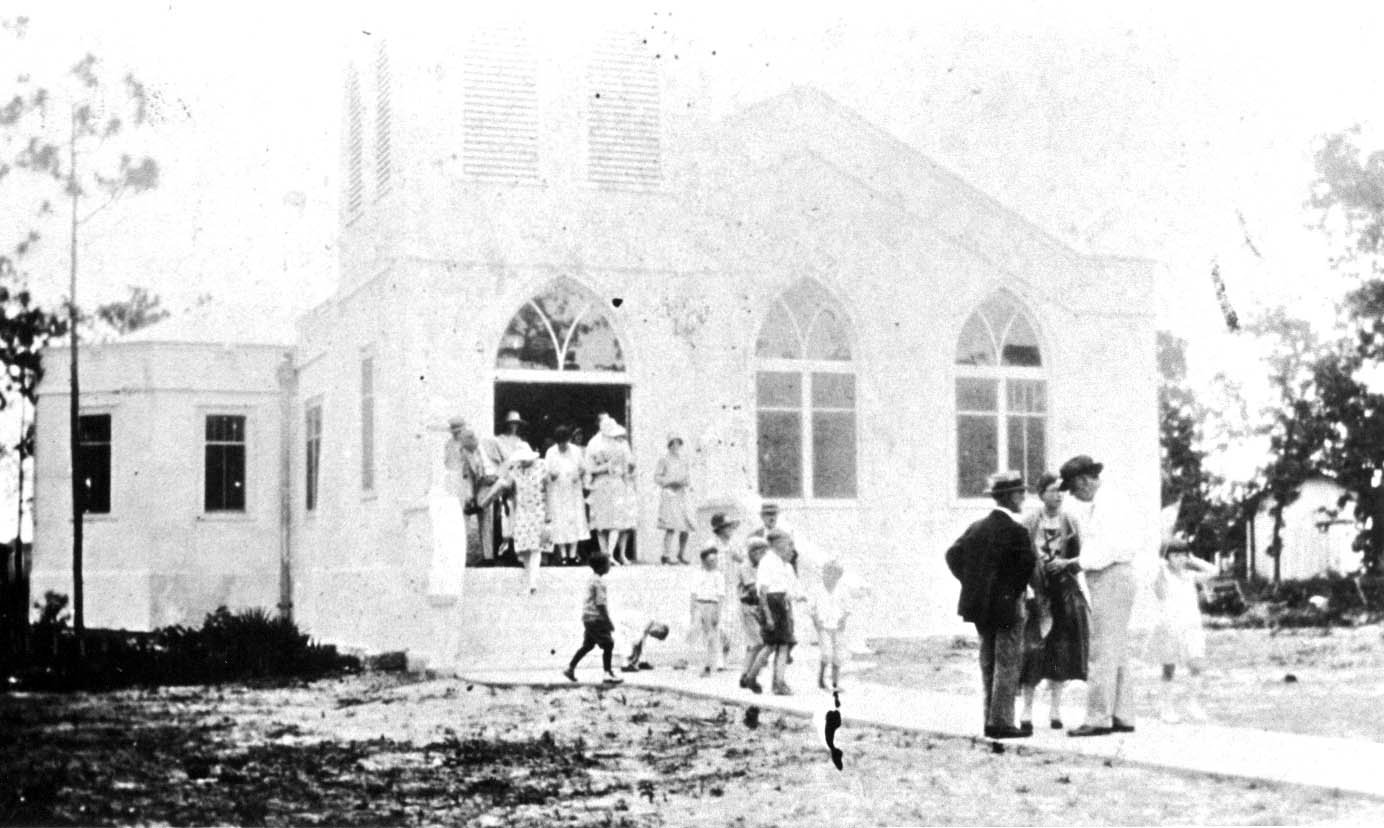

Madcap Laffs (12 min super-8 1974) was made in my first year at the University of British Columbia. It featured a narrative frame with a long dream set between. I filmed at night so that a black field would allow patterns of light to move through the frame — it’s mostly reflections in water and glass, shot in the city. It’s about alienation. Like much of my work it develops from some emotionally upsetting experience. Some of my films have romantic leanings which are dismissed today because they fail to take account of social and political issues, but it’s simply about feelings. People have feelings. Often I’m interested in looking at a work and seeing what state it reflects in the artist. When the whole society is out of balance it’s manifest in the art created in that society. When I began work in the early 1970s the trend was to regard film as film. Today the trend is towards a politically aware and correct cinema. In 1974, I went to the church where I’d been an altar boy for years. I hadn’t been there for a long time and arrived on Good Friday, the day commemorating Christ’s death on the cross. I felt it wasn’t right to go inside the church to film the mass, so I decided instead to shoot the people walking out. I shot one roll of 8mm film and later re-filmed this on a variable speed projector. By reviewing it at a slower frame rate, each face, each gesture is exaggerated. It allows you to see ,this line of mourners that runs back over two millenia. This became Good Friday (13 min 1975). This slow evacuation from a death many still haven’t gotten over wasn’t visible in normal time. It taught me that some actions aren’t visible at ,normal speed, like flowers blooming or clouds passing over a city. Often time has to be compressed or expanded in order to see what’s really happening.

MH: In the Vancouver Art and Artists Catalogue, Al Razutis wrote: “Good Friday evokes a Catholicism that is medieval, ritualized and somber. The grainy, step printed procession of people exiting from a church on Good Friday is framed within Gregorian Chants that suggest an ironic counterpoint to grace and conversion. This steady procession is evocative of Standish Lawder’s Necrology where humanity passes through the gate of the camera on its way to some deadly destiny.” Do you agree with that reading?

PL: What people get out of the work doesn’t necessarily speak to my intentions. It doesn’t mention the film’s three movements, for instance. The second section evokes stained glass in its use of changing colours and the third section was made at a different time altogether. I went back a year later and filmed the same scene with my 8mm camera. Only I shot the second part of the roll upside down and didn’t have the film slit, which produces a four-screen effect in 16mm. So a title announces “One Year Later” with these four screens — the two frames on the left show the people leaving the church while the two frames on the right show the people walking backwards into the church, because this side is being projected backwards. Some of the faces are the same as the previous year.

In 1975, I attended a course on avant-garde cinema in Massachusetts, and one of the guests was Ondine, who showed Warhol films like Vinyl and Chelsea Girls. They took a very different approach to avant-garde film, and when I got back to Vancouver I set about making my own underground films. I Was a Teenage Personality Crisis! (20 min super-8 1975) follows the sexual frustrations and misadventures of my friend Fred. At the beginning he masturbates, then browses through girlie magazines which inspire him to go the beach where he meets Liz. He invites her to a party he’s having but her biker friend arrives and beats him up. He invites another woman, but she’s in bed with another couple so she doesn’t come either. The party that ensues is 100 percent male — just a bunch of guys getting high. The soundtrack edited together bits of popular music and Fred ad-libbed the voices in one session. I did it as a parody, not thinking of it as a serious film at all. I think it does capture a certain spirit of the times, it’s my American Graffiti. [laughs] I made Personality Crisis in the summer and the next year at school I began work on Spare Parts (10 min b/w 1975).

In Spare Parts I was inspired by modern music scores that broke from tradition — especially composers like Cage and Stockhausen. I was also reading the cut-up novels of William Burroughs, whose techniques I tried with various paperbacks of my own until I learned to read in a different way. In Spare Parts I related some of these interests to film. At the University of British Columbia they’d received a number of discarded films from the National Film Board which I used as source material. The first of the film’s four movements shows a trio of divers jumping off a board into the water, and then repeating the shot backwards until they’re back on the board. It’s a “trick shot” and the original voice-over says: “And the cameraman puts them right back.” I took this original trick shot and had it printed twenty times or so. After showing the entire shot, I divided the shot in half and showed it A.B., then B.A. In the third repetition, I divided the shot into five equal parts — A.B.C.D.E. — and showed all the possible combinations of these five, eg. C.D.A.B.E., C.D.A.E.B., etc. Then I divided it into thirteen sections, because the shot was thirteen seconds long, so each shot was one second.

For the second section of the film I decided on a prison sequence using four different sections from an individual film entitled After Prison —What? One shows a prison guard, another a prison yard, the third a prisoner banging his cup against the bars, and the fourth shows the guy getting out of jail. With four elements there are twenty-four possible permutations and the film plays out these variations. Unlike the divers sequence, these prison scenes don’t repeat, but develop simultaneously. Because the sound lamp on a projector is twenty-six frames away from the gate I made every shot twenty-six frames long, which means that you’re always hearing the sound from the previous shot.

In the film’s third section I took six sequences from six different films — all dealing with some kind of anxiety. One shows a boy asking a girl out for a high school date. Another is from a film called What Makes a Good Leader?, which shows various people talking about the qualities of leadership. The third is set in a living room where a couple are cleaning up and wondering what’s going to happen to their daughter who’s going out on a date. The fourth shows a dive bomber in the Second World War. The fifth shows Arctic explorers entering the unknown. The last shows people watching a film. I thought of this section as a meditation where the mind watches itself because it allows an audience to see another audience, who are watching another audience, who are… After selecting the sequences I needed a way to organize them. So I let each one correspond to one side of a die — one through six — which I rolled 360 times to determine the score. As in the previous section each shot is twenty-six frames long. So if the die showed three, then I cut twenty-six frames of number three in; if it showed one then I cut twenty-six frames of number one in, and so on. I felt their simultaneous presentation was a kind of miming of consciousness. What’s incredible is the way these six different films seem innately connected. In the film’s fourth and final section, I took twenty-four single frames and performed twenty-four permutations. This section is twenty-four seconds long. Most of the images are industrial — heavy machinery and the like which relate obliquely to the apparatus of cinema. The soundtrack is just sprocket holes. I called the whole thing Spare Parts because it’s made out of these used, discarded films. It’s like a junkyard of images. There’s a West Coast tradition surrounding found footage. I think people’s approach to image making on the West Coast is very playful. It’s a form of collage, an ecology of images that recycles garbage, it’s the blue box of filmmaking. The East is more cerebral, it’s where the criticism comes from, where the academy resides. Still, it’s hard to generalize too much. I remember that when Ed Emschwiller came into town he said that in the late 1950s, his work was characterized as abstract expressionism. Ten years later people said the same films were about the psychedelic drug experience. In the 1970s people said they were about male-female relations.

MH: It’s like that line from Culler: that meaning is context bound, but context is boundless. I think the real problem comes when the work stops speaking at all, except as a kind of historical curio.

PL: When MTV hit the airwaves in 1983, they used so much stock footage that I became discouraged from using it — now it seems like a mainstream technique. Everything from perfume commercials to the introduction to “Saturday Night Live” uses stock footage. In my last year at the University of British Columbia I made Eye Dentified Image (5 min 1976). It was a portrait of a friend. I shot eighteen frames of him puffing on a cigarette and used these in a series of variations to produce the film. It was photographed indoors in a very orange light against a very strong dark background, like Rembrandt. The smoke patterns become visible in the slowed motion of the film, each frame is frozen and chain dissolved together. I zoomed closer and closer before the final sequence shows a superimposition of close-up abstractions which look like solar flares. It ends with a zoom-out which shows the entire frame. This burn-out was my good-bye wave to the university.

That summer I began work on Processed Gello (5 min 1977). I was on a macrobiotic diet and increasingly aware of food, so many of the film’s images relate to eating. I found them in a tourist promo film for Florida. Searching for a way to order the images, I turned to Schoenberg’s twelve tone musical scale and adapted it for film. Each of the twelve tones was assigned a colour — with white corresponding to silence. It’s a further evolution of Spare Parts, whose mathematical permutations provided a visual score that the imagewas subject to. I built a contact printer with David Rimmer to make the film on, bi-packed two loops, and ran them through a simple colour melody. I see these four films — Good Friday, Spare Parts, Eye Dentified Image and Processed Gello — as my art school period. Eventually I cut pieces out of all these films to make Experimental Rhythms — it’s a structuralist “greatest hits” reel. All four films begin with footage that’s optically manipulated in a calculated way, using strategies that are foreign to the original material.

In 1975 I was twenty-one and embarked on a Greyhound bus trip across the United States. I bought a super-8 camera with three rolls of film, hoping to shoot thousands of miniature slides, one frame at a time. Sitting opposite the driver at the front of the bus I began to shoot roadside Americana out the window. Later I blew up the footage onto a number of 16mm stocks — giving each section of the trip a distinct feel. Each of the single frames is frozen for five, ten, or twenty frames — a duration derived from my heart beat. If the heart beats seventy-two times per minute then one could produce temporal fractions — a ten-frame duration acting like a half-note, a five-frame shot like a quarter-note. This would eventually become Trance American Impressions (30 min 1977). The film follows my trip down the West Coast from Vancouver to San Francisco where there were some pretty tough looking guys hanging around at five in the morning when we pulled in. I’m not very tall, so I just sat in one of those plastic chairs where they have the coin operated televisions and tried to avoid making eye contact with anybody. I took a trolley through San Francisco running to the end of the line, and shot some of that. Then I traveled south to Tijuana where I walked to the Mexican border shooting from the hip, frame-by-frame. Then it moves through the southern States and arrives in New York. The New York section runs from Harlem to the Bus Depot and ends with one of my musical heroes, Miles Davis, playing at the Bottom Line. During the trip I’d been taping radio stations across the country and I finished by taping this concert. I made a shortened version of the film called Western American Impressions (20 min 1978) which ends in Texas. A lot of the footage in the southern States shows black people which I cut out. I just wasn’t sure how it would be interpreted.

MH: You mean simply showing blacks on the screen might be considered offensive?

PL: Yes, because I was photographing people.

MH: Were they doing weird things?

PL: Not particularly. Nobody ever said anything, but I didn’t feel comfortable because of people’s sensitivity about how ethnic groups are represented. I was alone during most of the trip. It’s good not always feeling tied to someone, you need time to think. But sometimes it gets too much, a long way from home, looking out of the camera’s dark box, the dark box of the bus, into a road that replaces one infinity with the next. And money makes the world go round. If you’re not throwing money at hotels and restaurants you’re not treated in a friendly manner. [laughs]

In the fall of 1976 I got $5000 from the Canada Council to make Trance American Impressions, and I also made Home Movie and Reflections out of that grant. I left home in May 1976 and when I’d come back to visit I’d bring a camera along — usually video or super-8. When my parents came to Canada they left all of our family behind. I never had the problem of getting sick of my relatives because we never had any. One day I took my Bolex over and began to shoot my sister and parents, using extreme close-ups — forehead, nose, ears, mouth. It was a way of pointing out my origins, the physical links between us, of showing myself as a physical extension of my parents. I included some photographs of my parents when they were young to contrast with the way they look now. It’s the same person, but they don’t look the same. When I see the film today it’s evident that my father was close to death, the lines on his face show excess drinking, bad lungs, and imbalanced diet, but it’s tragic because they were his only real pleasures. He died shortly after I shot the footage. It was very difficult emotionally to work with these images with him gone. It became a kind of ritual, a way of dealing with his death and the breakup of the family. That film became Home Movie (12 min silent 1977).

MH: The film literalizes the notion of the home movie by shooting the home itself, and using it as the exclusive location. Was that a conscious strategy?

PL: Yes, at the time I was also shooting Reflections and I felt they were two aspects of the same gesture. One dealt with family relations, the social and personal, and the other dealt with being connected with a greater natural world. One was inside and the other outside. Home Movie’s construction is very simple, just one shot cut to the next without sound. The fact that it’s silent is appropriate because in our immigrant household there wasn’t much language, only simple expressions. Often there’s very little movement in the scene except for the changing qualities of the light, and this was enhanced by periodically opening and closing the aperture. The camera often takes a turn at the window and opens the aperture, as if the outside is opening up to admit the presence of the inside, to allow us to see what’s inside. The aperture’s movement seemed to bring in the two polarities between which the film was forced to work — between the white-out that washed away the image and the darkness that made everything disappear. It’s a very quiet and meditative film which allows the intimacy to come through, which is one of the reasons I was reluctant to exhibit it. I didn’t just want to throw these personal images out in the world where people would be insensitive to something so personal. The film scene was still obsessed with structuralism so it seemed out of place there. And the art scene in Vancouver featured a lot of parody — Mr. Peanut running for mayor, leopard-skin saxophone quartets, all this Dada-meets-conceptualism-meets-Canada-Council-grants.

MH: Your early work looks like it runs into two kinds of making. One stream is taken up with Good Friday, Spare Parts, Eye Dentified Image, Processed Gello and Trance American Impressions. These are structural works which are trying to develop new compositional techniques. You generate material and then subject it to a number of ordering strategies, whether Trance American’s heartbeat radio patter, the spatial mathematics of Spare Parts’ montage, or the mathematical schema that generates the colour overlays of Processed Gello. Then there’s another strain which deals in diaristic psycho-dramas. Julia Dreams, Madcap Laffs, I Was A Teenage Personality Crisis!, and Commercials For Free are all dramatic expressions keyed to the emotions of a male lead who is trying to connect with the outside — whether through woman, nature, or music.

PL: There are always these twin peaks: on the one hand the act of representing people, which invokes identification with the subject; on the other a more abstract work, which invokes identification with the image itself. These compositional strategies often came from modern music or painting. I never wanted to make just one kind of film, to develop a single, personal style which had to be repeated over and over — like Bruce Conner or Michael Snow. There’s a diversity to my work that explores a number of interests. When I started making films I was quite concerned about newness and originality; fifteen years ago you always felt that what you were making was new because it was an avant-garde film. That isn’t true anymore, because the avant-garde has become so institutionalized. As far as being on the leading edge is concerned, it’s not really an issue for me. Everyone has so many influences now, our thinking is so dependent on so much that’s around us, that it’s more difficult to make the necessary separations that define something like an avant-garde. I remember after showing Good Friday I was approached by a Vancouver artist named Tony Onley who felt I should go out and film people walking out of movie theatres, bars, restaurants, everywhere. But the last thing I wanted to do was to get locked into doing a series. That’s good for the galleries who sell artists. I’m always trying something new for myself even if it’s not new for others. In the 1980s I started experimenting with some of the very earliest processes used to generate colour on film. So while it’s an old technique, it was new for me, and that’s always been important. If it’s not a discovery, then what’s the point? Perhaps the art world would have accepted me more readily if they’d been able to identify a Pete Lipskis style but I’ve done just the reverse.

MH: Is there an avant-garde now in Canada?

PL: A lot of what’s considered avant-garde looks like a recycling of old avant-gardes. I think avant-garde resists the temptation to conform. Today there isn’t much of a technical avant-garde — where are the technical frontiers? They’re in the corporations; expanding the language of cinema is being taken care of in the boardrooms. After punk rock in the 1970s, outrage has became a style, hardcore pornography is mainstream.

MH: Tell me about Eclipse (5 min silent 1979).

PL: Astronomers announced a total solar eclipse in Goldendale, Washington. There’s a wonderful miniature replica of Stonehenge thereabouts where I hoped to film the eclipse. But the hotels were full and it was raining so hard you couldn’t see the sky, so we ended up driving back to a hotel in Portland. In anticipation of the eclipse I set up the camera looking out on the street and in the corner of the frame is a television set which showed live coverage of the eclipse. I ran one hundred feet of film at sixteen fps (about five minutes) during what they call totality. So the film begins in darkness, then slowly gets a little brighter on the streets. I kept changing channels, which were all showing different versions of the eclipse. The film juxtaposes the reality of the eclipse on the city streets with its media version. As you probably guessed, one is a whole lot more sensational than the other.

MH: You touched on the documentary with Home Movie and Eclipse, but Dance Masks: The World of Margaret Severn (33 min 1981) takes a more conventional approach to portraiture.

PL: Dance Masks features dancer Margaret Severn who was born in 1901. There were no ballet companies in North America so her mother left for London. There she saw Nijinsky and Pavlova performing in the Russian Diaghilev ballet and was very inspired. After the First World War broke out, she went back to the US, taking odd dancing jobs where she could find them. There she met an artist working in New York who made beautiful theatrical masks. She worked in some big productions and was a hit in the 1921 Greenwich Village Follies but decided not to follow the company on tour. Instead, for the next seven years she performed with her masks in vaudeville shows across the country. Vaudeville was a bit like the Ed Sullivan show — they showed movies, musicians, comedians, acrobats, and magic acts. She performed before thousands of people but she wasn’t an innovator or dance modern like Martha Graham, so she was forgotten. During the 1920s she was one of America’s most famous dancers; there are press books full of articles lauding her work. I guess that’s how it goes — some people are famous for fifteen minutes and others are famous forever. Dance Masks was a way to remember, to bring something back. Like my later colour experiments it’s a way to resuscitate a forgotten spirit. The film combines old photographs and films, Margaret’s paintings, and studio dances using her masks. From the beginning I was against shooting a talking heads documentary. I wanted to show her artistic vision at the height of her creativity, not concentrate on what this seventy-nine-year-old woman looks like today. The soundtrack was recorded one afternoon in which she answered a series of questions. She’s very articulate, and I cut the track to produce the voice-over that runs the length of the film. When I finished editing picture and sound I applied to the Canada Council for a finishing grant. I asked for six thousand dollars for this thirty-three-minute film. They said forget it. I got a phone call from a local documentary filmmaker who’d been on the jury, who felt I should shoot some more NFB-style interview footage to make it longer. I explained I’d intentionally not shot any of this footage. He thought I would have more success with the film if I added another twenty minutes because I could sell it to television. But Margaret and I were happy with it the way it was. She was the oldest person I’d ever known and I was worried that she would die before I finished the film.

MH: You made four films whose theme is colour. Each borrows and reworks antiquated colour processes. How did you get interested in these old technologies?

PL: In the early 1980s people woke up to the fact that we were losing our film heritage because the original negatives were unstable. They called it the red scare because old colour films were turning pink. Reading about efforts to preserve these films got me interested in colour separation and early colour processes in film. The Technicolor process, for instance, didn’t have this problem of fading because they ran three black-and-white film strips through the camera at the same time, with red, blue, and green filters in front of each strip. Black-and-white stock is much less susceptible to fading than colour, so Technicolor prints look as good today as they did when they were shot. But Kodak introduced the Eastman monopack, a single strip of colour film which replaced the three-strip Technicolor, and that’s the stock that’s causing the fading problems. In 1982 I received a Canada Council B grant to research colour separation. What I discovered was that there’s a lot more to the history of film colour than Technicolor. And the more I looked into it, the more I was fascinated by the inventors working in the early decades of this century. They were inventing a new apparatus and exploring uncharted territory. I learned about the differences between additive and subtractive colour — today’s motion pictures are based on subtractive principles, where a white light moves through coloured emulsion projecting that colour on the screen. Additive colour on the other hand, is the basis of colour TV. There, white light is created by combining the three primary colours — red, green, and blue.

Motion picture exhibition in the early part of the century was becoming increasingly standardized — everything from projection rates, screen ratios, equipment, and the type of colour process used were subject to a uniform standard. Two additive methods developed at that time died out because they weren’t practical for mass exhibition. The two types of additive printing were called “optical shared area” and “mechanical successive frame.” In the successive frame process, the black-and-white film is filtered with a rotating disk in both camera and projector. One frame is filtered with a red-orange filter, the other with a green-blue filter. When they’re projected, the frames alternate colour but because of our persistence of vision they blend, producing a flickering colour effect. It was patented in 1906 and called Kinemacolour. Before that films were tinted, toned, or hand painted. This was the first time that filters had been used to induce colour. The Red Car (4 min 1985) was produced using this method. Using colour film, I shot a friend painting his car. This was re-photographed onto black-and-white; alternating frames were exposed with an orange filter and a blue-green filter. I also re-photographed it with red, blue, and green filters, alternating every three frames — so I used both a two-colour, and a three-colour additive process. It flickers a lot and this is the reason the process failed — because it caused eye strain and “fringing” on fast moving objects.

Colour Experiments (13 min 16mm on video 1985) continued my interest in colour separation, using a method to simulate the three-strip Technicolor process. I set the camera up on a tripod and filmed parade scenes successively with red, blue, and green filters. I edited the original footage onto three parts and had them printed together. Everything stationary in the shot would be rendered in “natural” colour, while moving objects would show some variation of primary and secondary colours. The film opens with Queen Elizabeth in Vancouver in 1983, filmed in Kodachrome super-8 and blown up. It shows the whole state apparatus gathering steam around the Queen — the Mounties, the escorts, and motorcade. The final section of the film shows a fireworks display, a closing moment of spectacle. I shot the original in black-and-white, had a high contrast black-and-white copy made of the fireworks on double perf film, then flipped it around so it would be backwards, and printed both rolls with two different colours. So the image is essentially symmetrical, while the colours aren’t.

2-Tone (Aquarelle) (10 min 1986) was originally a film I bought from a collector in the States. It’s a documentary short about a French Olympic swimmer in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. It’s very artistically done and much of it was shot underwater, which is nearly abstract. I felt if I did something with this film it could be seen again. I printed the whole film onto double perf stock, which I flipped around and printed with its original — so they form a semi-symmetrical image. The A roll was printed with red light, and the B roll, the mirror image, was printed with blue-green light. The result is a symmetrical movement through water, washed over by both dominant colours. I didn’t think it was necessary to add a soundtrack, especially in the age of music video where everything has a music track overlaid. There’s a beauty to the silence — when you go to an art gallery you don’t need muzak to appreciate a painting.

The Green Flag (7 min 1988) is another film that reworks found footage. I took the first minute from a 1970 documentary about the Indianapolis 500 auto race and repeated it seven times, subjecting it to different colour variations. In auto racing the climax of the race is really its beginning because all the cars are close together, everything building to a moment of maximum speed. In Colour Experiments, I simulated the three-strip Technicolor by shooting chronologically with red, green, and blue filters. With The Green Flag, I wanted to make a colour separation of something, so I chose this one minute of exciting film footage. I had it printed onto three black-and-white negatives — once each with a red light, a green light, and a blue light. Colour separation demands three black-and-white stencils, one for each emulsion layer, which are printed together to produce a colour image. What I did was shuffle these layers and come up with some variations — each a minute long. The film’s seven minutes begin with the race footage in black-and-white, followed by six colour variations.

MH: Is there a relation between the colour variation and the race?

PL: No. I liked the footage because it had a green flag which acts like a green light, as well as a yellow flag in the pace car, so you can follow their colour changes through the variations. The cars move very quickly, and fast moving objects are one way to test for registration. If it’s off, you get a lot of blurring and fringing. But the registration was perfect.

MH: GT 86 (18 min 16mm on video 1986) follows your interest in cars and racing. What does the title stand for?

PL: “GT” stands for grand touring. It’s a kind of racing car. For me these are like avant-garde automobiles, not made by struggling artists but by multi-million dollar corporations. Part of being a filmmaker is the machinery, a fascination with tools, hardware, and technical processes. I’ve carried on a love affair with race cars since I was young and wanted to convey some of the excitement, as well as the ritual ambiance of the race. It’s like a modern Valhalla in there, an old male ritual of fire and noise. In the second section of the film, cars are running through the pit lane while the sound rolls at half speed. In the third section the sound is restored to normal speed.

MH: Does art preach only to the converted?

PL: Of the thirty people who came to my show in town last year, half of them were my friends. But I don’t intend to change what I’m doing to reach a larger audience. To reach the most people in this country you might as well work for Hockey Night in Canada.

MH: At what point does the practice become elitist and self serving?

PL: When the artist becomes arrogant. Art’s suffered because of the art bureaucrats but as long as people go to art school, there’ll always be someone who wants to do something different. I remember the review Debbie McGee gave Dave Rimmer’s films in the Georgia Straight. She said these films are a good argument for abolishing the Canada Council.

MH: But that reviewer is likely expressing the views of most of the audience.

PL: There’s so much entertainment out there the market is saturated. What can you do? Line people up at gunpoint to watch your films? It’s a dilemma. The bottom line for me is to keep making work I think is interesting. I don’t lose sleep over audiences. I’ve remained pretty much outside of the official institutionalized art scene. I’ve lost faith in the integrity of the Canada Council and the film co-ops. I’m not optimistic, I’m cynical about a lot of people’s motives. But as long as I’m fascinated by moving images I’ll keep making work. There’s always something new to discover.

Peter Lipskis Filmography

Julia Dream 3 min super-8 1973

Madcap Laffs 12 min super-8 1974

Good Friday 13 min 1975

I Was A Teenage Personality Crisis! 20 min super-8 1975

Spare Parts 10 min b/w 1976

Eye Dentified Image 5 min 1976

Processed Gello 5 min 1977

Trance American Impressions 30 min 1977

Home Movie 12 min silent 1977

Experimental Rhythms 20 min 1975-77Western American Impressions 20 min 1978

Reflections 15 min 1978

Commercials For Free 20 min super-8 1978

A Face in the Crowd 30 min super-8 on video 1978

London 5 min 1979

Eclipse 5 min silent 1979

Dance Masks: The World of Margaret Severn 33 min 1981

It’s a Mixed Up World 8 min 1982

Hollywood and Beyond 12 min super-8 on video 1984

Colour Experiments 13 min 16mm on video 1985

The Red Car 4 min 1985

Crystals 4 min 1985

Time Capsule 37 min super-8 on video 1985

2-Tone (Aquarelle) 10 min 1986

GT 86 18 min 16mm on video 1986

GT 88 18 min super-8 on video 1988

The Green Flag 7 min 1988

Another Day 7 min super-8 on video 1989

On and Off The Road 80 min video 1991

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Spare Parts: The films of Peter Lipskis

Peter Lipskis has worked for two decades, producing 24 short films and a number of videos. Across Canada, there are just a handful of makers (fewer than ten) who have been occupied with the task of artist’s media work for as long. And none have been as prolifically obscure as Lipskis, nor could any boast his range of expression. Taken as a whole, his oeuvre displays frank contradictions and shifts in interests, alongside enormous thematic and qualitative difference. While the scrutiny of an artist’s output generally reveals personal obsessions and recurrent themes, leading one to speak of a “body of work,” Lipskis’ filmography seems crafted from a multitude of perspectives.

In the 1930s, French poet Andre Breton proposed a movie-going method whose patrons would enter cinema in the midst of a film and leave before the plot cohered, rushing into another theatre showing a different film where the experience would be repeated. In time this notion of an exquisite corpse, an automatic writing of cinema going, would become the multi-media spectacle of the 60s where flashing lights, slides, multi-media screens and live music would create a sensual sensorium. Away from the tribal outfits of the 60s, this sutured image flow has once again realized an individual expression with the advent of multi-channel television. “Grazing” quickly from one channel to the next, it is not uncommon for viewers to follow three or four programs at once. Peter Lipskis’s Spare Parts is a precursor to this development, an image of images to come.

While attending art school in the mid-709s, Lipskis studied under one of the reigning deans of Canadian structuralism – David Rimmer. Emerging from New York in response to the romantically subjective cinema inherited from the Beats, structuralism’s cool agenda was in fact a transplanted modernism. Taking cinema itself as its object, it typically established each work as a limited arena where a single formal gesture was put through its paces. Spare Parts (1975) remains Lipskis’s most provocative and enduring document of his structural interests. Clipping a single shot from an educational documentary on film, he divides the shot into sections and replays them in various chronologies. The original “trick” shot shows a quartet of divers falling into a pool then back onto the diving board to their original position.

While this shot is little more than a camera effect, Lipskis resuscitates this moment by showing the divers performing a series of gravity defying acrobats, extending its conceit of a plastic and reordered time. Plumbing the possibilities of a single moment, Lipskis arrests our attention, too often given to the relentless present-tense flow of media presentation and pauses to consider a single thought in motion. This suspended or arrested attention emerges as much from the divers’ attitudes- as in the gesture of reclamation itself, searching through the dumpsters of thematic history for a shot that could speak once again. In reviving moments unremarkable even in their original context, Lipskis suggests that there are no bad films or bad shots – but that the join between image and viewer is the most important splice in a montage.

The aptly named Spare Parts is composed of four sections – all comprised of discarded or “found” footage. In Spare Parts’ third movement, Lipskis excises sequences from six films, divides each into one second segments, then proceeds to montage them altogether, offering six parallel and simultaneous lines of development. This gesture of intercutting films while permitting them to maintain their individual narrative content presents a story of spectatorship. Forced to acknowledge the codes of narrativity (and our own recognition of them), we are watching ourselves watch these films, delightedly as it turns out, as each drama turns to its inevitable end.

The notion of audience as construction worker, actively piecing together the evidence before them is a structuralist conceit, opposing the monumentality of an abstract expressionist cinema with one which is simply present, with a cinema which plays alongside its viewer. Its resolve relies on an engaged spectatorship who find their own way of arranging the elements before them. Imagined as a dialogue, structural cinema attempts to meet its witness “half way,” asking the audience to perform alongside the film. As one famous structuralist avowed, “This is a film about you, not about its maker.”

Lipskis would make periodic returns to a structural cinema over the course of the next two decades. Good Friday (1975) slows the step of a departing church assembly in an elegiac rite; Eye Dentified Image (1976) shuffles eighteen frames of a friend smoking; Eclipse (1979) frames a television set displaying a live eclipse and an open window showing its effect on the street, both in a single shot; Crystals (1983) animates the infinitude of crystalline structures; and Another Day (1987) is a fixed-frame, time-lapsed portrait of the entrance to Stanley Park. Photographing a frame at a time over the course of a day from a single vantage point, Lipskis shows a mad tumble of busses and people as waves of citizens make their way into the park, the flow gradually subsiding before an elegant sunset draws the day to its close.

But Lipskis’ interests are too wide ranging to be contained in the structuralist canon. While re-arranging stock footage at art school, he spent his summers shooting super-8 in a style influenced by Warhol’s 60s narratives. Hoser movies like I Was a Teenage Personality Crisis! (1975) and Commercials for Free (1978) are fueled by sexual frustration and a post-Oedipal frenzy. Both episodic narratives feature Siggy Magic, a friend of the filmmaker, who entertains the familiar middle-class litany of sex, drugs and music. As he muses in a fast talking voice-over, Siggy is refused sexual favours, browses porno magazines, gets high with the boys, buys new clothes, gets turned around in a dance club and sings the blues. All in a night’s work. While there is little to recommend their reviewing, it is interesting to note the series of dichotomies which these two films demonstrate in opposition to their structural counterparts. Lipskis structural work is made of 16mm, black and white found footage, arranged according to pre-meditated formal strategies. His super-8 dramas are shot himself, edited to tell stories, filled with personal incident, and set in a Vancouver cityscape familiar to the filmmaker since birth. This schizophrenic manufacture would herald the many shifts Lipskis’ work would undergo in the next thirty years.

In 1981, Lipskis completed a half-hour documentary on an aging dancer, Margaret Severn, for whom he would spend the next decade caring. Dance Masks (1981) is the testament of a 79 year old woman whose dancing career brought her around the world in the days of vaudeville until mechanized entertainments like the cinema would render her profession obsolete. Bringing classical dance into the music hall, she fashioned her own masks and choreographed her own dances, high stepping in front of crowds used to more lugubrious entertainments. In Dance Masks, Severen’s voice fills the soundtrack, noting events with the same indomitable will that saw her through the best of times and the worst. Her speaking is interrupted only by her solitary dance performances. Masked and costumed, her ballet gives life to gossipy dowagers and estranged lovers, and finally to the four seasons of the rose, a dance which underlies her own mortality even as it celebrates her youth.

These dances were performed decades before, with no existing record of them, so Severn mounted the stage for the last time to perform them again. The risk in these recreated dramas is unmistakable – that she should appear pathetic or merely ordinary, her aging form a shadow of that madly passionate dancer that lit stages across America. Her filmic success speaks of a courage that belongs to the imagination and to the deep-seated relation between Lipskis and Severn. Deeply felt and movingly photographed, Lipskis brings a powerful intimacy to his subject, wrapping her past and present in a glowing wonder of light. Although much of its form is conventional, its emotional resonance is not, as it brings to notice a forgotten history.

Only once before had Lipskis ventured into the realm of personal cinema – with the simply named Home Movie (15 minutes 1977). It is a silent documentary of his home and family. Begun with a lyrical watch over window light and kitchen tile, he approaches his subjects cautiously, circling once more over familiar furniture before alighting on his sister and parents. When he finds them, he abandons the lyricism of light and shadows and confronts them directly, photographing them head on in a succession of rough hewn stares. While his mother is drawn through lace, his father is a bulbous nose filling the frame, and then an ear, and then a mouth. As this cataloguing of personal details continues, the filmmaker appears to be searching out his own origins, in the body of his father, noting the resemblance to his own features, drawing them out with the camera’s elongated stare. Lipskis moves from the home’s architecture to an architecture of flesh. While most home movies are made by fathers to preserve (and control) the image of their children – to gain control of a reproductive process which is always partly fictional for a male –here the familiar trope is reversed. Lipskis encounters his father as an image, as a fleshy prophecy of what his son might become.

The generations are pictures in solitary. Each member of the family sits alone, doing little, as if sitting for a portrait. His father smokes a cigarette, his great sausage fingers filling the frame in a close-up. He pulls at a beer. In a few short months he will be dead, his last moments left behind here to remind us that the past, the present and the future are three dreams which cross in the mind. Like Dance Masks, this film is a work of mourning, the quality of attention brought to its framed enclosures in the watchful eye of one present at a wake. Lipskis brings us with him in these protracted journeys of remembering.

In the early 80s, concern over the instability of the dyes used to add colour to film led to widespread industry concern over the preservation of film history. Keeping abreast of new archival methods, Lipskis found himself drawn to the history of colour film, and to the various techniques used to render colour before film labs standardized. He resuscitated these techniques in a series of films which include Colour Experiments (13 minutes, 1985), The Red Car (4 minutes, 1985), and The Green Flag (8 minutes, 1987). Colour Experiments’s hallucinatory blend of state spectacle and a go go techniques mark it as a challenging and accomplished work. Working with a simple, hand-cranked Bolex camera, and changing the filter, the result is a multi-coloured phantasmagoria of urban pomp, replete with fireworks, floats and marching bands. The superimpositions show layers of streaming floats passing as if in a dream, the sedative nature of spectacle passing in long streaks of colour.

A pair of automobile excursions complete his reformulation of the colour process. The Red Car is an enthusiast’s short. He watches a friend spray paint a car bright red before taking it on the road. Lipskis uses an additive colour rendering to augment and underline the chromatic gestures of his subject, blending form and content. The Green Flag takes an auto race as its subject, its brightly coloured hulks of transport turning about a circular track like cinema reels. Following the race depends upon a colour coding which the filmer places under because of his interventions.

No discussion of Lipskis’ work would be complete without mentioning his obsession with automobiles. Celebrating the fetishized speed machines of auto racing, Lipskis has produced GT 86 (1986), GT 88 (1988), and the feature length video On and Off the Road (1991). These video studies are devoid of voice-over. He is intent, instead, on exhibiting a universe of machines, a show case of interchangeable surfaces whose track-bound revolutions are never narrativized into a race. Eerily dislocated, they are anomalous documents of a fan, like the personal scribblings left in the margins of a book. Never stopping to speak with any of his subjects, he is content instead to show the passing of steel and chrome, an outsider with an insider’s understanding. And while the handheld camera signifies a personal subjectivity, there is little in the image to suggest a personal rapport. Everything is glimpsed at one remove – distant and alienated. As one film gives way to the next there is the uncanny sense that they constitute a protracted and ongoing self-portraiture, albeit on oblique one. In its tireless display of auto flesh, Lipskis’s On and Off the Road may be likened to one of the most radical audio-visual documents of the past decade – the Simpson Sears catalogue, now available on laser disc. This catalogue compendium, radically non-linear, reflexive, and interactive, is an image for a cinema yet to be realized.

Originally published in Reverse Shot, 1994.