Our Peasants

The title is already a picture: Profils Paysans: L’Approche (Peasant Profile: The Approach). A ninety minute film by Raymond Depardon. As soon as the movie opens my expectations are confirmed and thwarted, sure enough, we are traveling in the French countryside, and the exemplars of a life no simpler for want of an internet connection are almost all past the age of retirement. Though there is no retirement from this way of life, only the grave. What is peculiar is the compulsive chatter of the director, in his beautiful French voice. (Was the voice-over invented to allow us to hear the French language without the distraction of the mouth, the red herring of the body?) The journey begins with a sad string accompaniment, but no sooner have we traveled a few seconds then the voice begins, impatient to wait a moment longer, there are stories that need to be told, or at least, the frames of stories, ghostly contours. The voice announces the opening of a journey in the third person, while we haven’t met anyone yet, already on this side of the camera, the watchers are multiplied, the look is already a consensus, a compact. It is ‘our’ journey, though it’s clear that while the viewer may be privileged (or bored or irritated or enthralled) to look through the eyes of this multiple, ‘we’ is the property of reproduction, the apparatus. And for that the viewer has come (as always, there’s no escaping it) too late.

The first subject is introduced, an elderly farmer, shaking with Parkinsons, but sternly capable of keeping her own house and animals. The director continues to speak (of course!), pronouncing her name, a recent tragedy, the barest sketch of her present circumstances. She reads through her newspaper, trembling as she turns the pages, and never looks at ‘us.’ What I am waiting for is the decisive moment, never mind that they are missing from my own life which proceeds in a haze of indecisive moments and vague gestures. In the cinema I am granted that rarest of blessings: intimacy without consequence. (I enter the cinema in order to enter the lives of these characters, yes, I’m not afraid to say it, even in the documentary these lives are already fiction, these people are characters).

As I watch her reading her morning paper I wonder why this shot and not another? What is being revealed here? What special, private moment has been stolen from the other side, from the impossible memories of this stranger, this witness, who will be laid open like a cadaver in a morgue for the viewer (for us!) to satisfy our restless appetite. Entertain me with your wit, your bravado, your tragedy. Convince me of your uniqueness, your singularity (Why you? Why of all people are we all watching you?)

She says nothing. The director tells us that a friend will come to visit, and when he does, they speak a language even the director cannot understand. Of course, he films it all. They keep their secret, their private life, for themselves.

Instead of waiting with the camera-hammer, Depardon moves right on down the road. He could wait in order to break her down, torment her with the expectation and weight of the camera, which is heavy precisely because ‘we’ are also waiting. The camera carries its audience in the lens, who while still imaginary, demand entertainment or confession. Beauty is a distant third choice. (Beauty doesn’t make you laugh, you can’t eat it, or follow it like a story. Beauty in the cinema is an extra, and in the documentary cinema, there is only suspicion (it’s dishonest! not rigorous!). Besides, as everyone knows, there is nothing political about beauty (or is there?).

But Depardon refuses this circuit of desire, content instead to chat in voice-over while his subjects eat, read, make coffee, look on sullenly (as if they were the audience, and we the subjects). A new kind of verité emerges, not cinema verité (with its first thought-best thought, transparent-truth ideologies), but a verité cinema, which carves out a space alongside its subject, who are neither elevated or depressed through interactions with the apparatus. The framing is careful, almost delicate, and above all frontal, like an Elizabethan thrust stage, there’s nothing to hide here. It’s important above all to provide context, the camera is set back from its subject to allow the windows and roof and chairs a chance to have their fifteen moments of fame. And there shouldn’t be too many shots, never mind montage, these are peasants after all, they can’t afford montage, it’s too expensive, they belong to a world of mise-en-scene, of patience rewarded after waiting for harvest.

The farmers small talk, working out the details, the necessities, a cut on the hand, today’s price for calves, the accumulation of firewood. In place of feelings there are inseminations to consider, bulls to be borrowed. The actors are old enough to play themselves, unrehearsed and unadorned, no one has put on their best suit. But while we are privy to a serial table talk (a concerned neighbour comes to visit, a vet to disinfect the animals, a young couple who will take over the farm. Yes, all the visitors are young, but when you’re past seventy, the world is young.) ‘We’ (the audience, the uninvited) are never quite comfortable behind the fourth wall. The fourth wall, the place which we are granted at this table, is not an easy place. The subjects are wary (what are you doing here?), clearly the camera does not belong, and neither do we. This is not city life, where strangers climb in and out of view on every street corner. Depardon, the director, refuses to make the way any easier, to bring us any closer. He leaves in all the looks towards the camera for instance (which occur dozens of times), and there is always his voice which while apparently dishing information (“We are back again in…”) marks a border, reminding us with every breath how much is being left out. Here is a tempered display which measures just how much will be revealed. It’s like listening to your favourite rap song while watching the VU meters in a mixing studio. Depardon’s remarks make an object of his voice, pulling us out again and again from behind his camera and its veil of reproduction.

It is a reflection, finally, of what belongs to the world of reflection, to the cinema, the cost of pictures, the division of private and public space. The farmer’s son hides in his own room, preferring the consolation of anonymous pictures on television to the immediacy of his own capture (though when he is introduced he is clearly posing, camera ready, the guard is up, he is ready for his close-up, but for how long?). Verité cinema: a reflection of reality and the reality of reflection.

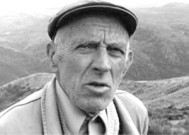

A two day negotiation, hard bargaining for cattle, occurs over a kitchen table. Though negotiation is a kind word for this digital exchange (on-off, yes-no). Comically the exchange carries on (and on) even while the buyer (who is also a friend, a comrade, an enemy) drives off, and then the next day. When the terms, which have never changed, are finally settled, the old farmer walks away from the departing truck back towards his house (the reliable, and steadfast) as the camera jerks in an awkward pan towards him. He stands there a moment, peering into the lens, granted at least the dignity of the last word, which is also a comment on cinema, on the documentary. Admission, dismissal, accusation. He turns to us, to the lens and announces, “Those sellers are all the same. Tougher than the rest.”

Originally published in: Dok Revue, a newspaper published by Jihlava International Documentary Festival, 2004.