To the Guggenheim committee,

I’m writing in support of Robert Todd’s application for a fellowship. He is the premier lyrical filmmaker working today, with an unparalleled sensitivity to light and emulsion. He has single-handedly updated the aesthetics of the New American Cinema with a quietly dazzling camera technique that finds the secret life in our vanishing forests. It is an ecological cinema first of all, a cinema devoted to climate change in this perilous moment. His primary tool is attention, the traditional device of the avant film artist, though Rob applies his attention via a musical series of theme and variations, allowing us to enter the life of what many would name the background. Here he corrects the errant visionaries of past generations by applying himself to a post-human perspective, bringing us, in an increasingly prolific exposition, the expansive life of the natural world.

I’d like to say a few words about a couple of Rob’s past movies. They are each the result of a deep dig, here is an artist working from the nerve ends of his experience, somehow able to summon each silver wound and press it into the present moment, as he opens and opens again. He is the heir apparent to the legacy of Stan Brakhage, the lyric avatar who steadily converted most everything around him into some very first person vision quest. But while Stan’s hyperbolic camera stylings were themselves an extension of abstract expressionism, and not only in the decades of hand-painted work that closed his book, Rob’s camera collaborates with his subject, his camera breathes together with the grass and flowers, and brings them forward in all of their mystery and wonder.

It is a radical place from which to undertake the visual essay that he wants to undertake in Matter, a sort of visual manifesto of climate change. He doesn’t lay it down quite like this in his statement of plans of course, Rob is not an artist who begins with words, he maps the world with his body first of all, “the whole body at once is the teacher,” as Deborah Hay used to say. Not least because he needs to abandon his descriptions while shooting, in order to receive the here and now. So before I spell out my support for Matter I’d like to spend a few moments looking at some of his past movies, in order to tease our some germane concerns, and to give you some idea of how this artist works.

In his devastating short Arsenic (12 minutes 2011) Todd creates a portrait of an aging woman whose memory is failing. Her language appears as truncated stabs, failing descriptors, reaching for a subject that is always slipping away. In place of her face there are drapes and the exterior world glimpsed through the veil of those drapes, everything exists as interrelated layers, dreamy and slipping right on by. The hope of the movie seems to be about what those failings might make possible. What about the glow in the room, those unnoticed light secrets? And then there is a long journey into night, where the turning display models of someone else’s imagination turns into primal reshapings, what Freud named, so beautifully, the dreamwork. And then we are brought back into the daylight again, back to the stumbling, the reliance on old familiar defenses. And still the light continues, waiting to be noticed.

Portcullis (8 minutes 2011) begins with the sound of a winch cranked up as the camera tilts up over a gate. It brings me this question: what is the obstacle: the shadow or the thing itself? The movie is a vibrant exploration using Rob’s signature mix of color and black and white. The natural world appears alternately as a field that is staked out and guarded, but then again as a place where human observers project our defense structures. The movie asks me: have we constructed the entire world out of our defenses? Or even: how can we let go of our medieval constructions, that we have recast as garden backdrops? Can we let go of centuries of fortifications, in order to open to this moment just as it is, or are we still leaning on these orderly bars and containers to give this world shape, meaning, coherence, order. It is about the violence of form.

In these two short works, Rob works out of a location, which becomes a situation. Over and over again his camera turns apparently ordinary moments into a dramaturgy, and the conversation that he recounts is largely shorn of language or human figures. His magic is that he is able to transform bushes, the light falling on a leaf, a post stumped into the ground, into some necessary relationship, that is then remapped and revisited, rearticulated as the film draws forward. He has an uncanny feeling for musical form, and turns each element until it becomes part of a moving whole. I might as well confess: I don’t know how he keeps doing it. He is one of the most prolific artists working in the fringe today, as if he’s always at work, building those particular aesthetic muscles.

What he is proposing in Matter is something on a different scale than the miniatures he has spent so much of the past two decades refining. He’s still going to be out there in the landscape, but now he wants to join these in a symphonic series of unfoldings. From the melting ice caps of Alaska and Iceland, to the deserts of New Mexico. As his dynamic and lyric cinema has proposed again and again, everything is alive and emitting light and breathing. He is awake to the smallest changes, and what he is proposing is to gather the attention of these changes, collecting each local instance until an entire topography is mapped out, and then joining them with similar kinds of changes. But then a vital turn in the project, which is to show how attention itself is strained through the material, woven deep into the core of the machines of reproduction, and how those strains are already part of the unquote problem, part of an interminable series of interventions that are hurtling us towards an unsustainable planet. Or so the scientists keep telling us. How can the artist take up arms against himself, show up his own tools as part of the colonial register, part of the extractions? This is also part of the art of looking, and having arrived “too late” to the avant movie showcase, like everyone else who didn’t roll out their hits in the good old days, he has learned a thing or three about his own shifting subject position and how it continues to replay old cultural notes, even when it might appear like inspiration and intuition. Rob’s delicate focal shifts are also trained internally, the movie may also bear this self-examination, as it unfolds and turns inwards in alternating measures, the same way an exhale gives way to an inhale.

The keynote is collaboration. How does one collaborate with a glacier, an ice sheet, a river? How can one turn again to the natural world and not deploy it as a series of objects, as things that can be bent to fit other things, as parts of a relentless capitalist extraction? What happens in Rob’s work again and again is that landscape looks back. Perhaps that’s a funny way to put it. Is that tree looking at me? That leaf, that flower? We arrive at a glimpse of the secret life that teems around us. I hope you get a chance to see some of his work, though I’m guessing you will watch it on Vimeo or some similar digital platform, which is like looking at a slide of a painting through a muddy glass. Perhaps you might hear this whisper when you do. Because when you see those fragile, flickering creatures paling and blooming in the projector light, you know that at least for this moment the cinema is alive again. What are we, if we aren’t everything?

Mike Hoolboom, artist

Toronto, November 11, 2014

An interview with Robert Todd

I met him when he was still in black and white, in a diner at the Ann Arbor Festival. There was something about his face that seemed charmingly unfinished, chiseled out of some particularly American brick

which was soft in all the places a face should be hard. It was a face that said yes, even to strangers. Especially to strangers.

And he was quick to dismiss whatever new movie he was trotting out on the circuit. He would wave it away and speak only about the new fine hope he was working on, or the dream that was about to begin. Haunted by death, leaving the past behind, driven.

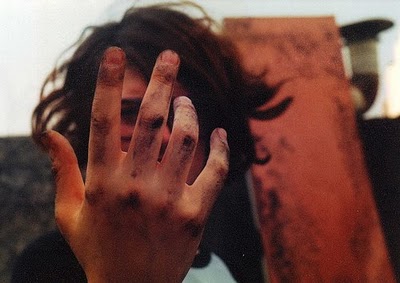

It wasn’t unusual then to be a committed avant maker plying your trade in 16mm, though as each year passed, the numbers dwindled. But not on Robert’s end. As if to make up for the rapidly approaching vanishing point for the analog world, he is busier than ever committing his seeing to a hand wound Bolex, following the light and becoming it. His tools are increasingly extensions of himself, his camera eye looks and receives, he is able to film in the deepest shadows knowing that some final shimmer will find its way onto emulsion. Teaching pays the bills, and so he is by necessity an urban dweller, but he has a particular feeling for the natural world, and lenses it with a sublime precision which draws the viewer through his camera and out the other side. With Robert’s work we are always at an intimate distance, a touching distance. He needs to bear witness, to take the risk of seeing from both sides of the lens. He was there while the men in maximum security counted the days, when his father died. He has a certainty which refuses mastery. The following interview occurred via email and has been considerably edited down from Robert’s voluminous and eloquent responses. As if at last he had been summoned to confession.

MH: Do you feel, as an American avant movie maker, that you have arrived “too late”? That there exists a “heroic” period of creation, marked by the 1960s, canonized in books and universities and the formation of seminal institutions, which have rendered the efforts of all those who have come after, like yourself, relatively invisible?

RT: On my own, I rarely think of this. My primary focus is on something that I’ve become excited about in the last rolls I’ve shot. My primary concern is with film’s interaction with light sources and how we come to position ourselves as either emitting, ignoring, baking in or hiding from light or dark (clarity has some place in this interest, too). Because my background is in drawing and painting, my major influences have not been filmmakers, though I have had strong responses to films that I’ve seen.

I feel that I “arrived” as a filmmaker at a perfect time. I was ready to make films when it was cheap and challenging and offered me things I could not find in drawing and painting but didn’t eclipse them. “Visibility” (recognition by others?) is far less important than my ability to experience the living and making of art. I feel fortunate to be involved in a dialogue with my own work and that of others whom I respect, but I feel more fortunate to have the time and means to make work, and believe that I am a worthwhile part of a conversation for people who share my concerns. That may be small-minded (or small-visioned?), but I have no grand aspirations around being canonized or broadly distributed.

MH: How do you mark your work in relation to this tradition of the untraditional? Are you walking in the footsteps, stepping in the shadows, or do you feel absolutely free of those constraints, the call of what’s been done before, the stoop of precedent?

RT: These questions are fun to consider, and not just because I’m a teacher. I don’t feel absolutely free of the constraints of this tradition—some of this has to do with how programmers and others see what I do, but much has to do with how I respond to things, as suggested above. I don’t see myself as expanding upon processes established by others, but I do see cinema as sharing a vast vocabulary of process, form and subject matter that I feel echoes of when I’m in the edit room. I’m not particularly well-versed in either cinema studies or the history of avant-garde/experimental filmmaking, but I’ve learned much from others as I’ve discussed their processes or seen their works. Most of these people have not been canonized, but I recognize that they’ve been influenced by myriad sources which necessarily includes films from the canon. Some of my strongest responses have been to films that have never been finished or have been to moments within super-8 films that have never been shown to an audience of more than two.

That said, there’s also something about short-format filmmaking that both allows for free artistic production and a quoting of/from the untraditional tradition. When I’m shooting, producing or editing, I remain flexible, but I form an idea as I go that becomes an organizing principle that gradually rules out notions of freedom within the overall experience (both of making and viewing). I’d like to be able to say that the precedents I follow are my own, but that’d be about as delusional a statement as I could ever make about my work. In the end, I’m looking at an outward reflection of my internal self, sometimes through multiple mirrors. Am I hedging here? It all seems slippery to me, like asking if I behave this way because my father did so, once, long ago…

MH: We run into each other whenever you have another film (or two or three) finished, and are back on the circuit getting it lit up. But you rarely want to speak about whatever brings you into town, instead, you are filled with enthusiasms about yet another new flash, another set of seeings which you are aching to realize. Your relentless work habits lead me to believe that you are trying to cheat death or something (why so many movies? why push so hard?), but also that you want to resist becoming “defined” by what you’ve just produced. On the one hand I feel you are absolutely committed to the shaping of seeing which each of your movie requires. But on the other hand, as soon as the finish line approaches I can feel you slipping away, leaving it behind, there will be no resting on laurels, no waiting to see what recent activities has brought to bear, instead you are already off in search of the next one.

RT: Cheat death? Hmm… I was speaking with a painter friend about what the process is like. She was talking about a series she’s making (49 paintings) that are phases within a transitional state. I said that this reminds me of what it’s like to be in the mode of making films—they are transitory and transitional: there doesn’t seem to be a state of completion. While making Qualities of Stone in May 2006 I became interested in some things which were shot through the summer and fall for There, which in turn led me to shoot in the winter. In each instance, I felt that there was more to say because when I watched the footage cut together, it was nagging at me, not like a problem, but like a solution that I was having trouble seeing. Shooting was a way of seeing more. I suppose this is akin to a scientist who’s noticed something, comes up with a hypothesis, gets slightly different results than expected and learns that there’s more to this discovery that need puzzling and exploring.

But this only captures some of the picture, I do have little fires that crop up, and I obsess about pursuing them. The film that I have already made is the record of a process of discovery which I’m only casually interested in revisiting. But the great thing about having my own program at Ann Arbor (2007) is to see several movies flow as a set, as if it was one movie made in parts. This larger view is exciting because it blends various mysteries together that make more sense than I could ever glean from a single film. Making is ongoing but has moments where a greater digestion and stock-taking is necessary. Few have been with me when I’m at that point, and it’s usually something that happens privately, when I screen a bunch for a few friends or myself. So I don’t resist being defined by my work, rather I am curious as to the nature of this rather fluid event and its revelations…

MH: Speak (7:30 minutes 1997) opens up from an identification with a newborn, offering grainy, negative solarized home movies and teeming waves as the poles of past and present. You rhyme slowed reflections in a bowl with clouds passing across a blue moon, mouthfuls of milk, blurred shapes which pass too quickly to be identified. Throughout the tape there are invocations of a speechless speech, a mouth before language (a woman is filmed so that the sun appears to blossom out of her lips, obliterating them in light, or lighting them up). A face (is it yours?) appears half submerged, speaking underwater, but there are no words. Who once wrote that no one really remembers childhood, what we have instead are memories of memories. Is this what your lyric impressions are delivering to us?

RT: Speak was constructed of texture and time ruptures so that all points of visual reference slip through and around each other, to be taken in as a gestalt. Memory is what we use to fill the space between the beginning and now. The body of the film (the space between these waves) is a collage of impressions that articulate the relations between the self and the sea it swims in. For me, the most self-conscious moments produce the greatest swells, and in these states, it’s hard to steer in a steady, singular direction, but in those moments I often “see” the most. “Seeing” in the sense of admitting a maelstrom that draws in all currents to shine its phosphorescent mix of memory, design, dream, emotion, revelation, insight. Not all of what we “see” we will to “see,” and not all such storms navigate to a safe port. This film, quite optimistically, doesn’t concern itself with destinations, only the journey (darkness and light).

MH: About your movie Clip you write: “For over a year I’ve been working on the subject of the Death Penalty and its significance to our culture. This piece has grown out of the footage that I’ve shot for that film, and some of the concepts I’ve been juggling. I had an idea that the imposition of a strict formulaic process to living imagery would drastically alter its appearance, much as the strict adherence to dogma can disfigure or even destroy a life. On my way to the beach to film waterfowl, I had the misfortune to witness a truck smack into a bird in flight and drive unflinchingly on. As I waited with the bird for help, I brought my camera to bear on it. It felt awful, as if I were revisiting the violence done by the trucker. It made little difference that my machinery was held at a distance, I was aware of myself imposing a violation on this hapless creature. When I saw this footage projected I was deeply disturbed, and felt much gut-wrenching empathy with this bird, and horror at the recognition of the camera callously whirring on in its fearful face.”

Clip shows a bird subjected to a maniacal optical reworking, layers collide and blend and melt away. As a viewer I wonder: why all this work on such ordinary pictures? I have seen it a few times now, but never knew “the story behind the picture.” And now that I read the story, the experience feels deeper, the pictures clearer. You are doing something akin to Brakhage’s Sirius Remembered, an ode to his dead dog. I think it began with a walk he took behind his house with a friend who doesn’t notice the dog lying dead at all, so Stan sets to work recapturing his dog’s lying, rotting last sights and post-death visions via a hyperbolic cutting strategy. You also bring a great load of re-looking to bear, is it so that you can control death, slow it down and start it up again? Or more simply to show how this ordinary moment is also (like every ordinary moment) extraordinary? Perhaps you could also talk about the ordering itself, you worked with a kind of “script,” didn’t you?

RT: The death you spoke of before (my “cheating death” through the bounty of making art) and the one that is mentioned here come not from places I see but only imagine. Where I’ve been touched by death (my uncle, my father, my grandmother: all of these were deeply affecting in ways that permeate much of my work, including Lost Satellite, family history, Fable, fisherman, Our Former Glory and In Loving Memory) is different from where I’ve seen the potential for death, and the re-working of that potential. The film also suggests the cruelty of non-participatory observation that is a sort of “death”—the death that comes from distancing. I feel that others have discussed this more eloquently than I could, but to put it in my simpleton terms: the camera can work as a story works—pantomiming an ideal state of being, rendering events in a way that suggests that immortality is possible. It reduces life to something wonderful, and places it within language. In the moment of observation, we are There, yet Not There because we allow the camera to weave a “story” around the event. In this sense portraiture becomes still life: the capture shows the relationship between myself, the medium, and the subject—a dance that removes my full attention and risk of everyday interaction and replaces it with a secondary series of interactions. A different type of life is lived, and the other potential life has been suspended or replaced.

When I would paint a portrait with the person in the room with me, the paper or canvas and all of the machinery surrounding the making can hardly be invisible to the subject, nor can the actions I undertake as I dance reactively to the material emerging in front of me. I change, and yet I wonder how the subject and the environment change? How do they react to what I am doing? Active portraiture, in which the subject moves, can allow for more incident, and a sort of shared authorship can take place, but, as with “directing,” the arbiter of the recording device is the one who holds the keys to the door to the world, which is the surviving evidence of the event. We agree to this relationship when we agree to “sit” for a portraitist, or to accept the camera into our lives. And in so doing, we close certain doors—whether or not we choose to acknowledge this is another matter, but it is the matter (the subject matter, in a way) of the film Clip.

The first “script” for the film was influenced by what was at that time an organizing principle for my life: my preoccupation with the distancing mechanisms that allow for the execution of our fellow human beings by our “society” in the loose political sense of that word. My gathering at that point was directed toward certain images that could hold potential for the larger film about prisons: beauty in decay or decaying beauty, the disfiguring of ideal or iconic spaces, the sense of an idyll within the commonplace. These were rather simplistic notions, but I was at the beginning of a journey and took the most obvious steps. I say this to emphasize that at this point I had a “story” to tell without the specifics—I had an organizing principle, and the world could expect little mercy from me.

I had shot the birch trees and one of the jails (among other things not used in Clip), and was on my way to the beach to shoot the water and birdlife there (one large piece of my life puzzle is that I have a familiar identification with birds, so an impulse toward shooting or drawing birds is also an impulse toward self-representation) when the accident described in my write-up occurred. I was bird-sensitive and already had an organizing principle, so the event was both shocking and fitting. The camera came out, and a kind of death occurred to the life I would lead (we would have led?) were it not so. As I shot, I further developed my “script” by choosing positions which gave the camera a character that became increasingly aggressive and agitated.

After shooting through the bird’s recovery (and having no help arrive from the Rescue League), I shot the birds on the beach. I thought some of this would make its way into the death penalty film, but I didn’t have a clue as to how that might happen. I was further shaken and embarrassed when I saw the footage projected. This was the beginning of the contouring of the “script.” I thought about my anger at the callousness of the truck driver, furthered by the callousness of myself as camera operator, happily distancing myself from distress. I felt compelled to voice this through an editorial act that would create the kind of harsh environment that my spirit found itself trapped within. I wanted to underline the cruelty of these organizing principles through hyper-stylization, creating a structure that would give life over to the machine. Mathematical formulas seemed a good choice because they were the linguistic basis of a machine unconcerned with content, so I created a form that I could fight against through my more romantic (content) choices as a filmmaker.

The formula: The imagery is spread across 100 feet of film, which is 4000 frames. These 4000 are broken into 10 sections of 400 frames each. The first section shows a single image from a sequence of images (shot A) held for 400 frames. The second section’s first frame is the second frame of (shot A) and its second frame is the first frame of another sequence of images (shot B), and these two images alternate for 200 frames, at which point (shot A) moves to the 3rd shot in its sequence and shot B moves to its 2nd frame in its sequence. Each section introduces a new image sequence (shot C – J), and divides accordingly (section 3 has 4 divisions of 100 frames, section 4 has 8 divisions of 50, etc.).

If one could say that a singular image suggests a disembodied sort of spiritualism (death), then unhinging oneself from the singular icon on the screen suggests a further denial of the original form from which the image was culled. The rephotography (through optical printing) was a recreation of the distancing effect of the shooting of the material in the first place, I could only concentrate on the counting down of the printer as I blocked and unblocked light from film frames to allow the formula to have its way with the film and my psyche. In the end I let the formula break down, and this seemed to satisfy the romantic in me.

In a way, the film reflects a kind of anxious epiphany—a hyper emotional state of affairs belied by the banality of the context found in the environments that surrounded the events that I’d shot. I found the banality as distressing as my own actions. I suppose I wanted to bring the epiphany (of life overtaking death) to the place that I felt it—didn’t my conscience come to the fore in the end? For me it did, and in reliving or reviving it I seem to have reaffirmed it, at least for myself. I haven’t made another film using that process, but the insights I gained have determined courses in other films made since.

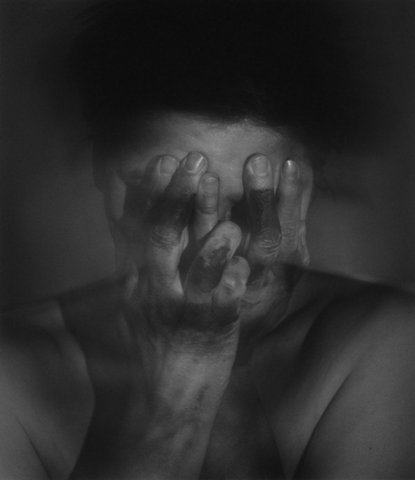

MH: Our Former Glory (9 minutes 2002) opens with a suite of negatives, beautifully rephotographed by you, looking closely at these faraway figures from another time. Why these pictures, and why do you keep them at a distance, refusing a particular moment, allowing the past to keep its secrets? Then you create a duet of faces shown in extreme close-up, intimate and melancholy, and a stubborn architecture which is aggressively reworked through rephotography, as if you are trying to crack these rigid geometries. Television appears as well, not as clip collage, but as abstract lines and white noise, the outside world appears as abstractions, there is little social space here, only the murmur of a lost interiority and the left behind, hand-made offerings to those “missing” in New York after the trade towers went down. Do you feel that your abstractions (which are derived from the world after all, they are photographed) are abstract? Or are they documents? Can you talk about how you structured this movie? Why the title? And what set you on the path to this making?

RT: When the first Trade Center bombing took place, the idea of the building as a symbol of commerce was emphasized by the media, but for me these buildings didn’t appear real—a unisex pair of unpeopled blocks. They distilled our notion of Empire into something gothic, the ultra-container advertising the generic value of the systems of capital and exchange that we’ve bought into.

A few months prior to their collapse, a news piece brought to my attention the fact that artists had studios in these buildings (maybe only one of them). A softening of the line? For me this was the first humanizing aspect of these structures that I’d encountered in my life (as a child I watched them grow…). The weekend following the collapse, I was due to attend a wedding of an old friend, and I went to NYC to meet up with another friend so we could travel to that event.

What was this collapse?

Americans once believed that liberty and commerce were tied together—the Trade Center facing the Statue of Liberty—but ironically, no sooner was the symbol for Commerce lost then the primacy of the commercial was underlined (Bush’s speech telling us all to continue travel and shopping as an act of strength and belief in the American way is still played at airports across the US), and the government quickly began curtailing Liberty as if it were an embarrassment. Within a few weeks, the American flag would mean something that few could agree on. We had become an empire long ago, and now the foundations of that empire was called into question around the world. Our Former Glory refers to this.

When I went to NYC, I took a walk along the Brooklyn promenade, and I brought my super-8 camera. I shot the memorials that were quickly becoming trash (the working title for the film was “trash”), and some other shots of the site of the former Trade Center buildings (along with a few other shots from my friend’s apartment). The memorials were largely cheap, gift-shop items bought from vendor carts, there was plenty of mass produced, impersonal plastic to go around. The starting point for the making of this piece was my reaction to those memorial items, what these cookie-cutter icons hoped to represent versus what they were quickly becoming, and the pathos found in the simplest of transient forms. This reaction was weakly conveyed in the footage. When I saw it projected, I didn’t have an idea of how it might change into something else.

I went to Ann Arbor that year and shot some super-8 in Detroit. I rode the monorail and concentrated on the motor of the camera, shooting single frame and 18fps. I shot the buildings that were swirling around me, and they seemed hollow and sad, maybe even a bit sickly.

I reviewed the “trash” footage, and was struck by the chaos, something I’d found a bit of in the Detroit footage as well, and then I noticed another similarity which was in the bar-coded materials that were in the memorials, the patterns of the flag and the buildings, and it hit me that this is what I would be working with: the visible language of commerce, juxtaposed with chaos, humanity, and an older iconic form, the circle (though that didn’t occur to me until much later).

The Bar Code (as a language) became the central character in the film, and the structure reflects my own feelings about this “abstract” presence in our lives. It is a language that we cannot read, but is translatable by machines. It is a mirror of binary computer code which defines the global social sphere’s functional communication and the means of its practical application. As a labeling device it has been tied to commerce, but its uses extend to the non-commercial as well. As I wish to suggest, the boundaries between the commercial and non-commercial have long ago eroded, and this film provides a portrait of that.

The structure is narrative and follows the transformation by cracking through rigid geometries in a visual battlefield that employs references to television, advertising and consumption and the concomitant obliteration of subjecthood. The film ends, oddly, on a hopeful note, where the “chaos” of human warmth is foregrounded through the hand-made pleas for info on lost loved ones, and the veil riding over the image of the lost towers.

The film begins in a mood which contrasts with the towers, leading from the telescoping shots of the past in negative and positive space, to the “intimate” somber shots of the faces which are disfigured in battle with the bar-code later in the film. The beginning plates slide through focus, they are meant to be intangible, suggestive and beautiful, recalling in a somewhat nostalgic manner, a time that we can glorify pictorially but not hang on to. Shooting those images involved careful selection (they were pulled from my wife’s grandfather’s collection, and I mixed family with travel, negative with positive) and construction (to bring us into the home, toward intimacy, but not in a direct or specific way). That care decays as the film progresses, so as the bar codes dominate, I was looking through the lens less often, shoving things in front of the optical printer randomly.

One interesting feature of this film is the soundtrack. Keeping to the language of the barcode, I translated the “Barney” (purple dinosaur) theme song into barcode, and then printed this onto transparent film using varying “font” sizes of bar code (this also produced the traveling mattes seen midway through the movie). I then ran this film through a 16mm projector and recorded the sound from the optical reader into Protools, and used this not only as part of the soundtrack, but also as a “gate” pattern for another major component of the soundtrack which was ten minutes of daytime television. The pure barcode sound is particularly grating, and meaningless to our ears, much as the noise of a fax machine might be.

MH: Thunder (11 minutes 2004) is a nature movie which shows the bulldozing of trees in your neighborhood. The rough, handheld super-8 footage of the fallen trees is framed with long, graceful passes of 16mm footage which, as usual in your work, is very beautiful. You show the remaining trees after rainfall and in the early morning light, in colour and in black and white high contrast. Your camera drifts up these old trunks, sensitive to the movement of stripped branches in the wind. It closes with a winter storm seen in dying light. The tendency you have to make everything beautiful creates an effective elegy for these fragile ecosystems trying to co-exist alongside houses and humans (though people are never seen here). But doesn’t the aestheticization provide a mask which hides the destruction that “nature” is forever carrying out? Isn’t the act of creating pictures a way of distancing you/us from “the natural world” (or is the movie theatre also part of nature)?

RT: In bourgeois society, landscape painting is the defining tradition for discussing nature visually. There’s the God version of nature (wrathful, hungry, expansive, outside human control), the Romantic version sees it as the setting for human experience, anthropomorphized versions use nature as substitutes for human characters or emotional states, and then of course there’s Impressionism that tunes nature to the key of whatever optics the paint favors. In photography this might be named pictorially reductive naturalism. Why this list? Because within these categories, flora serve as either window dressing, some portion of the Ground, or as a supporting prop within the works, not as the main Figure.

Scientific endeavors in the 18th-19th century were more interested in the character of floral nature, and through their inquisitive (empirical, positivist) taxonomic pursuits, a cold identification with the particular needs of plant life began to develop. Through these efforts, exquisite works on paper and in glass were produced which elevate plant life’s spiritual representation in a way that the American Luminists would never approach. Still, the project of “Nature” was known in either a more general Darwinian way, or, as the transcendentalists would have it, God’s business on earth (and if it’s his business, shouldn’t we be closer to it?). This had a hand in spawning, among other things, the bucolic cemetery movement, which in turn was followed by the hubristic call to “naturalize” portions of the new industrial cities. This legacy survives in our ideas of nature as both aesthetically satisfying and recreationally engaging. But in the end, it’s all still seen as a ground, while we are the figures, the ones who act. Hence they are subject to urban planning and human maintenance. As unfit subjects, they are disposable, replaceable, consumable. I mean to reassert the Subject of the plant as Figure in a portraitist’s sense. I see the tree in the center of town as a living being. Shackled, yes, but alive and with us. Through this identification, one can begin to posit portraiture. To make it happen in a meaningful way, as I suggest earlier, a kind of love must be kindled.

In Thunder, I wished to treat these Trees as individual beings, caught within the ambivalent forces of human desire. I wanted to encourage an engagement with these beings that might lead to beauty and narrative. So I let the color be the Ground—the space of beauty that you describe is an evolving sense of the artist’s discovery of some of the changes of the trees’ lives. There is a haunting beauty at the beginning of the film which is pushed into another realm through the destructive force of the crane. The death of those trees is the beginning of what I see as meeting, or facing up to, the attitude of disposability as a demon in the Western psyche. Winter is the acknowledgment of the destructive power of nature—the whitening of the world, purity interrupting life. It is the end of a long strand of color. The crows feed on its remains.

The hopeful note (I’m such a romantic, no?) is found within the stillness of the machine as the snow overcomes it. A special kind of Life can take place within the short space of a truce, even if it exists only in a spiritual or transient sense. All of that said, there is a struggle within my films concerning Beauty. In art making it appears as a kind of love, and yet I see that its conflation with idealized forms can lead to a split between life and the place we imagine it being (the transcendence of the ideal, something that art can facilitate). Thunder offers contrasting forms to break the sheen of the film skin. The shift in colors within the super-8 section, the green veil of the fence, the move from super-8 to 16 then back again as the storm approaches, the dim flat color and space of the tree at rest in the middle of the film with the machinery around it, and of course the shift from the glorious brown-and-white to the dull throb of winter.

I was also interested in breaking the film’s spatial sense in order to destroy any iconographic celebratory references, moving it away from the Olympia diving sequence and closer to Kubelka’s African experience. Perhaps I fail to make these differences meaningful for others, or register with their physical experience of the piece, but they remain for me. It’s interesting how we can wade through much that is non-beautiful to find small rewards, and how this process is akin to a relationship, and can also be beautiful.

Is the movie theater part of nature? If theater is part of human nature, yes. If the action of light on our perceptive minds can let emotions run like wind across the grass, yes. If we hold each other’s hands and stroke each other’s backs in the cinema like baboons on the plains, yes. If can plant something there that takes hold, grows, and reproduces, yes. If love is possible there (as I suggest in the creative act of representation), yes.

MH: In Stable (7 minutes 2003) you visit a farm with a keen attention to detail, the drippings of a pipe, the way light falls onto grass, or a horse’s snout, or the side of a building, one spectacular view follows another, but they’re not held so long. Don’t worry, your editing seems to suggest, beauty is everywhere and in abundance. You use a variety of film stocks, each with its own look, though the “subject” remains the same-or does it? Why foreground these formal transformations, and how has this rural visitation rendered the life “behind” these striking moments more vivid? Or is that beside the point? Farms (or so I imagined) are work sites first of all, but the only one working here is you, the animals are grazing or looking slowly into the lens, nature is growing “all by itself,” the farm (a container for the natural world, re-purposed as food) is presented as an unpeopled idyll. Isn’t this a way not of looking (which the film is very concerned with) but of looking away? How to begin to address the small farm at this precipitous moment, when farm suicides in India, Pakistan, and Argentina (to name only three countries) are occurring in staggering numbers, as small farms (like the one you depict in your movie) are driven into bankruptcy by “free trade” agreements (which keep food tariffs high, and farmer subsidies in first world nations intact), government coercion, and multinational monoliths like the genetically modified seed producer Monsanto?

RT: When my sister started reading books to her son, she was struck by how many stories used the farm or farm animals as characters; also notable were ABC charts and other language-building aids that referred to beasts and provided further fascination for children (and their parents) who are, for the most part, living far from working farms (they are much more likely to encounter these creatures at zoos, historical reenactments, or petting parks). Her response was to build her character lexicon from the creatures surrounding her suburban home—characters which the children would more likely encounter (outside of domestic pets this meant mosquitos, wasps, small rodents, etc.).

But the animal is only one small part of what’s held at a distance—the farm itself will continue to remain exotic for the suburb/city dweller. I just saw a short called Fail Better Farm (a student thesis project) that profiled a couple who had quit their jobs in the computer fields in order to rent a farm in Maine. Their pursuit was inspired by a movement to buy organic and local produce, and to distance themselves from commercial culture. But in the end, the mindset seemed wholly romantic, bringing to the fore a nostalgic stance that rings true for many bourgeois who feel that old “get back to nature” dream of Rousseau’s, as if some core set of values could be regained when one’s “living” is made through husbandry.

I had been shooting film on this farm for several years. There were things that caught my attention that I wondered about but had no answers to—the stamping of hooves, spots on a horse’s back, the color red. There was also the psychic attraction to animals, the life of a domestic, the weird romance of moving dirt. I filmed with an eye on most of these things (a few shots in Trauma Victim come from this shooting), but never with a serious thought of putting a movie together. The confused alienation alluded to in Trauma Victim increasingly took over, as did my churned up feelings about life in the face of death. I was deep into the death penalty project at this point, and Dad was up and down in health when I visited the farm one day and casually started shooting close-ups. My first focus was on the mutilated and decaying baby bird, and I recalled Clip and found myself looking on in horror, so further shooting was led by thoughts of reverence and sympathy. This turned out to be the overarching emotional lens that I brought to bear on the place.

I wanted to bring the farm alive in terms that replaced the pictorially grand or quaint with something that might move vision into mystery and wonder. I needed to feel the bird in this place, a site with a life cycle that would normally seem separate or beyond me, but here seemed to pass through me, bringing a history to the fore that I hadn’t felt before. My connection to Animal was hinted at through seeing the water ripple in a way that I found myself thirsty for. I found myself looking at things like animal time and animal focus. The sense of the animals having only this world to live in was something I brought inward. In this way, the film prepared me for seeing death as real (a place of resting and also profound ignorance), and seeing life as preciously beautiful—a play of moving colors of emotion, awareness and form that could find meaning in fragmented vectors.

With In Loving Memory I shot the exteriors of all of the prisons in a way that was intended to keep the viewer on the outside of the fence, to make no pretense of a possible understanding of a “true” aesthetic of the space within, the space that feature dramas and certain documentaries seek to unearth or exploit. My approach to the farm was a reaction to that idea, sympathetically showing what an interior understanding felt like.

Shifting textures paralleled shifting states of being. Using multiple exposures meant wrestling with ideas concerning control and direction—all of these multiple exposures were done in-camera, and my ability to impose a directed vision onto these events was challenged in interesting ways that wound up defining the editorial structure of the film. Stability became a principle feature of the piece. These images were at their most muddled (to the point of being unwatchable) when there was no organizing principle, but seemed trite when strategies were strictly adhered to. And this, I felt, was a pretty good metaphor for both vision and being, and one that allowed the images to win out over me and bring the subject (the life-place) into that reverential space that made it (for me) a successful portrait.

MH: Trauma Victim (17:30 minutes 2002) opens with fragments of seeing on the edge of the visual world, framed by tentative looks out a draped window. The world appears “too dark,” or “too light,” rendered in a spectacular montage of strobing green flashes and overexposed bathtubs. This opening movement gives way to a five and a half minute meditation on Niagara Falls, rendered in your customary lyric style, before we enter a blue, high contrast forest for a couple of minutes. The final ‘scene’ aggressively alternates a fence and a flapping sheet in the breeze (one takes shape in the wind, the other rigidly reshapes), before a final, enigmatic shot shows us a soft focused balloon floating in air. The voice of Robert Bauer floats under these pictures in a quietly questioning manner. “Carrying your own weight, it’s an uphill battle.” Who is he?

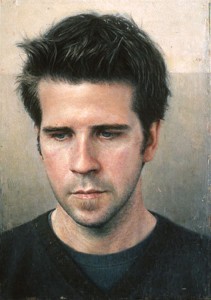

RT: Robert Bauer is a painter of portraits and landscapes who has a studio across the hall. He asked if I would sit for him, and insisted that I have a far away look, and then spent much time waiting for me to enter the appropriate zone before attempting capture of this mental positioning (posturing?). The end result reminded me of a mix of Lucien Freud and Albrecht Dürer, and I recognized a darkness that brought forth something hidden. So I asked that he return the favor and make an audio recording that followed the same process of waiting for him to enter a zone I guessed we might have in common (seeing that he could evoke this special place in me through a surface rendering meant to me that he had the capacity to arrive at that place himself). There is something about his voice-music that suggests to me a quiet strength, and a weatherworn life. I also see this in myself. I sensed in him the capacity for an advanced self-other portrait, where my sense of self was superficially aged, and I mean that texturally and reflexively.

The movie starts with an obscured image which feels more like distressed leader than anything else—it’s the balloon reprinted on black and white film. Following that is the light bulb suspended in mid-air. The bulb makes focus happen, and at the film’s end, this bulb winks out to white, followed by this distressed image followed by its parent color image of the fuzzy balloon. This image, like some of the Niagara Falls images, leaves the viewer in a suspended state, floating above the ground and not moving—a key metaphor in the film.

The distressed (or “barely there”) image is something to be pushed against or away in the beginning (the bulb is the arrival point), and as the film runs its course and we arrive in the field of bulbs, Robert’s speech about the “uphill battle” only leads to further questions which remain unclarified. When the bulb winks out and we are once again looking at the distressed image, the “answer” is one which leads us into the impossibility of the dream place—the world of the child, or even the pre-child. I see the end as regressive in that sense.

MH: How does his speech relate to the natural world viewings which occupy the visual field?

RT: Robert’s speech (my orchestration of his speech) is a plea for repression, and as it moves forward, it pretends to reveal an inner life. But the words do not “add up,” looking back conjures pain which he would rather avoid, or at least he would prefer not to name the source of pain directly. This is akin to not allowing language the keys to the heart. The images that I spin out suggest a movement away from pain—the dream within this Dream are the movements that take us away from the tub (the centerpiece of the film, the place where we relax, space out, imagine ourselves healing). The sequences of “Natural World” evolutions are conjured dream images that suit his will to escape but as they develop, they come to reflect the pain he seeks to avoid.

MH: Why the extended visit to the Falls?

RT: The waterfalls are extended until they become unbearable. They begin in beauty, deep within a water-spa, then decay into a thin and fairly aggressive environment that can no longer soothe (neither as water, nor as tourism). This is a reference to the pretense of the healing power of the Bath. The gluttony that accompanies our obsessions and fantasies of comfort are less important to me than the sense that the fantasy has run away from itself and crossed into another realm into which we’d (I’d) rather not have arrived. There is a fairly clear sense of spatial displacement in this section when one considers the position of the camera/viewer. Other pieces of the film move us “away” from plausible real space (via abstraction, or the use of different film stocks) each time they move us toward the pain.

MH: What does the title mean?

RT: There was a complicated series of thoughts that led me to the film, and they buzz around this title. I had ideas about our country, how we allow and even encourage each other to function in a state of permanent adolescence. I’m not talking about the drive to appear youthful, but the will to achieve an identity based on adolescent comfort, certainty and reduction. The icon for this state is the car. Our neighborhoods are prisons locking out non-domesticity, and the car is an extension of that lock-out. They are based on fraudulent notions of our ability to name ourselves, because we cannot see through to the essential event—the social being that lives within a world of difficult creatures who do not speak our language, of places that, on the surface, cry “inhospitable!” The inability to look inward or open outward, to rely instead on comforts that, if examined deeply, may lead to death. We look away from our own pain and the pain we cause by being this way. These features call to mind a state of trauma. I place myself within the ranks of the traumatized, because I, too, have my own inaccessible fountain of pain that comes from not having my feet on the ground, but floating in the air high above the reality that this civilization denies. We are locked into a Sky Castle that relies on ignorance, distancing and self-deception to keep its momentum.

MH: Your cross-country epic “documentary” In Loving Memory (47 minutes 2005) takes aim at maximum security prisons across America. It opens with a collage of voice-overs, unusual in your work which is very circumspect in its use of language. This chorus of voices answer a series of (unheard) questions: what is your happiest memory? What was the nicest thing you ever did for someone else? Thirteen minutes into the movie a phone caller mentions his incarceration, this is the first hint that this beautifully lyric movie might have a darker side.

While the first “movement” is filled with a blend of natural imagery (trees, flowers, water) and apartment interiors (magnificently lensed, of course), the second movement brings us to the prison(s), and a series of calls from death row inmates follow. As the movies progresses you seem increasingly constrained by your subject. Your lyric, intuitive style is battoned down by the numbing repetition of punishment, and the vast store of information which arrives in a very long series of intertitles. I can imagine you came across a whole lot of relevant, vital info on your travels and researches. Can you talk about the use of titles to dish this material?

You leave the greatest shock until the closing credit: the speaker’s we’ve seen in the film’s moving opening passages are identified as actors. Why actors? Why not name them as actors right away?

RT: The obvious subject of In Loving Memory is the memory of life in the face of imminent death. In addition to the movement of landscapes from lush fertility to arid desert, there are characters who tell stories and we see them in their homes. My hope was that because of the tone struck in the first series of images—the wide open landscape, the beautiful but somber close-ups, the oxygen tube and pills, the mixture of faces, ALONG WITH the title’s reference to the epitaph—the viewer would be oriented towards the character’s relationship to death, and so direct sympathies towards the identification that fiction and poetry allow for. Still leaving open the question of who these people might be. By having the first voice arrive from an answering machine (it’s my sister, and I think it’s apparent that this is from a relative, an intimate), the question of why some of voices are from phone recordings is suspended. This withholding brings a confusion that we can be comfortable with, it allows us to invent a community of storytellers, and invent our own feelings about their situations. But it is a sort of imprisonment that I offer. It is revealed that at least some of the people are (or have been) incarcerated at a point that is deep within the interviews, at a time when the landscape and other imagery has revealed its problematized development. The film continues to withhold, but now in a less kind way. There is a larger reference to our political situation here, in terms of the pretense we have that we “know” the scope of our own agency, our ability to affect the political landscape, but also that we “know” our neighbors in a larger national sense. As more is revealed about these things through sustained attention and/or contact, the more our previous restrictions are unveiled, and the more complex these situations are revealed to be. Naming the actors earlier would defeat the illusion of openness that allows identity speculation.

I was aware of the restrictive nature of prisons for those incarcerated and for the public at large. For some this is the raison d’etre for prisons—to keep this distinction sanctioned (sacred?) in every possible way. Originally I thought of setting up interview-like conditions at the prisons, but I didn’t like this thought for a number of reasons.

First of all, from a practical standpoint, I couldn’t imagine actually being admitted by the prison authorities. I knew that journalists were allowed in, but that otherwise only family members had easy access. There were some who had been able to gain entry, but when I recalled the results they seemed unsatisfactory. Secondly, by using actors I might gain a sense of shared humanity that placing them inside the prison would obliterate. I thought of filming them in some special way—faces only, shallow depth of field—but I still wasn’t happy with the flat nature of the representation.

The third reason was that the interview situation could color their responses based on how they were reacting to me. I wanted a situation that would allow them to speak to the world at large (a naive conceit, I admit), so I realized at that point that their words mattered much more than the encounter or the visual representation. I decided to call them. The only way to do this, as it turned out, was to write them and have them call me. I wrote to prisoners across the country, some on recommendations from people like Kazi Toure (American Friends) and others because I was interested in a particular State as a representation of one that had a lot of people, a few people or somewhere-in-between number of people on death row. It was a lot of letters. Some states sent my letters back before they reached the prison, but most seemed to get through. The letters asked that the receiver either write and mail their responses back to me, or that they call an 800 number that I’d set up so I could record the responses. I had a fairly low level of positive response, and because I couldn’t count on a specific time for anyone to call, my producer and I had to monitor our phone-with-tape-machine from 7am to 7pm from June to October. But it was worth the wait.

One thing I liked about this set-up was that the inmates were not asked questions cold, without a chance to consider their response. I was happy with the written responses—some were brief, and others extremely long, but all were a mix of public and intimate that made them interesting.

Outside of showing the written text, there was only one way of having them available in the film, and that was having someone else reading them. I had initially thought those readers would be people from my neighborhood, but instead I turned to people who could commit to a sustained work schedule throughout the fall of 2004, and this meant actors. We worked for two months on the audio performances, and went through various interpretations of what an “effective” performance might mean, and I recorded all of these sessions. This allowed for a variety of textures, something I could work with in structuring the movie as a reveal of “information” over time. Sometimes the same voice seemed to be representing very different characters or narratives (in the film sequence, immediately prior to the “incarceration” line, the performances become a bit stiff, and there is subsequently an alternation between flat and nuanced performance levels until the voices of the actors are heard no more).

As far as the shooting went: I sought out all of the state prisons in the US that housed death row inmates. I picked up non-death-row-housing prisons as a result of (apart from a bit of bureaucratic slight-of-hand) not only an interest in some of these, but also because early on I had experimented with interior prison shooting in the abandoned jail at the center of Boston and this served as an aesthetic touchstone for me in the film. It was yellowed and dirty, decaying back into a state of nature through neglect, and I found this helpful in considering what else I might shoot in the US landscape when approaching other prisons from the outside.

I gained access through the public information office in each state’s Department of Corrections. Once permission was granted, I had to contact the warden at each prison. In some cases guards would accompany me on my rounds, in other cases I could proceed unsupervised. In some States I was allowed access to the inside of the prisons, something I had not planned on, but these visits did provide me with useful shots.

“Useful?” Yes, the cinder-block-only death row cell interior contrasted beautifully with the rich apartments seen at the beginning of the film. AND I thought that the viewer’s titillation at being led inside death row should be particularly unrewarding and unromantic: broad empty spaces with big fat bars and surly men and too much fluorescent light. When I began shooting the non-death-row prisons, I settled on the idea you mention: that the richness of my “intuitive style (is) battoned down by the numbing repetition of…” the environment of incarceration leading to death. So I let Restriction rule, leaving the prisons to stand taxonomically embalmed within titles that reflect nothing but distressingly cold facts: listing the number of inmates awaiting death in each place. This succession would lead, I hope, to questions about why these numbers, and when will I escape the relentless march of these images? I mean for the audience to seek escape from the weight of these facts over time, like a prisoner forced to pace (physically, mentally) in his or her cell over the vast tracts of state-regulated time that we seem to be stuck supporting. Is this asking for hope to spring within a structure that offers no hope?

While I was making this film, my father was dying. At first this was not apparent, but in the Spring of 2002 (a year after I began making contact with the prisons) my parents were notified that he had kidney cancer, the disease that would eventually claim his life. At first I wasn’t aware that there might be a connection between my choice to make this film about life in the face of death, but over the course of that summer, I served as caretaker to my parents’ house while he was either undergoing treatment or in recovery at the hospital, and at that time of intensive reflection on the film and the struggle that was happening close to me I began work on what would become Trauma Victim. This film strengthened the connections between my filmmaking and my particular state of mind/being. The definitive connection came when visiting my parents at a motel. During that visit my father was recovering from surgery, enduring increasing pain, and his recovery (his life) was in jeopardy. They sent me to the pharmacy which was a drive away—too far it seemed for me to make it back with the medication in enough time to be of any use, and I sped shaking like a reckless crazy person down the road. My fear was palpable, and I was on auto-pilot, I had been reduced to an animal state, reacting with all due impulse and emotion to this situation. A life was at stake.

As my father went through recovery, it seemed that he’d been granted a reprieve—an old story, no? The months that followed seemed to be good ones for him, but the sense of fear and urgency remained for me. So from that point of view, this personal crisis did not leave me through the further stages of making In Loving Memory. However I did not imagine that images of my father or any direct references to our family’s story would enter into the movie. Apart from that, in spite of their conservative view of things, my parents seemed to be taking an interest in the film because they could see that it was a major priority for me. My father in particular was undergoing a spiritual change that made him much more engaged in the lives and projects of those close to him. It was becoming increasingly easy to fold my work into my life, as far as these connections with my family went.

In November of 2004 I found myself in Arizona, visiting the last of the prisons in a vast dustbowl as the sun was setting. I had just left the guard station and was losing my light while setting up the tripod for the first shot when my cell phone rang and my father asked how I was doing. I couldn’t talk, and he was in physical distress (the cancer had migrated to his lungs). It was a very sad moment for me. I was paralyzed, and saw the bind I was in as an emotional one, a staging ground for my own inability to easily share my feelings and thoughts with him, directly outside the only maximum security prison I’d encountered that had no windows to the outside world. It was then that I realized that our “story” was folded into the imagery I’d been shooting since 2000. When I got home, there was a message on the answering machine, the message from my sister that is the first main piece of vocal material in the film. A week later I made my way down to my parents’ house with two short-ends to shoot some of his medication bottles and oxygen machine, as supporting material for some of the shots of one of my actors which included the oxygen tubing (also at the beginning of the film). I still had no thoughts of shooting my father. Before I shot, I helped my father up to the sink, and I could feel a rising terror within me, and I didn’t know where it was coming from. He lay back down and seemed glassy-eyed to me, but it was hard to distinguish this as something different from what had come to be his “natural” distressed state. I began shooting, but I hadn’t gotten far into it when I realized that I had not taken any footage of Dad for a while and I would just take one unobtrusive shot from the other room. Very soon after that, it was apparent that he was in an accelerated decline, and a nurse was called. Soon after that the ambulance was on its way. The last shot of the roll I’d been shooting was the EMTs lifting him up on the stretcher. I felt this situation was happening out of my control, I was in the car again, speeding to the pharmacy, trembling. I ran into a closet to reload, and that two minute roll should have been light struck because I was in such a state in the closet (another metaphor for my withheld communication/emotions?) and I ran out to film as they led him out of the house and into the ambulance and away, away, away. Can you cry from behind the lens? I could. I went back into the house, both parents gone, and shot the empty bed, and realized that this was the last material I would shoot for this film, and would become the centerpiece. I recalled the voices of the men from Missouri describing their work in the hospice programs at their prisons, and the insights that they’d earned from those experiences, and they came to stand with me there, as I shot the empty bed and the bottles of pills with the name “Todd” on them. I didn’t consciously realize that my father would not be returning to this house, but I think I knew that he was nearing his death. I could not really face this. The “facing” of it would come a short time afterward, immediately prior to my sister’s wedding when he was there but not there, and I could see in his face all of the connections we shared, communicated or not. I understood that his passing was my passing, and that he would live in this way in this film, the most sacred project in my life. His “role” is spread throughout the film. Through the distress in his life he became (or joined) the Human Face in the film (you never hear his voice…), and it is his world as much as the other participants’ that is decaying around him, allowing a kind of clarity of thought and feeling that is sometimes obscured within the riches of our everyday taken-for-granted opulence. I am here expressing the personal side of this film, which is only one side of it for me, yet it is a side which I feel now contributes to its political potency by further wedding my presence to the material, showing the author as more than a casual observer or clever constructor. Since then I have been more actively incorporating the life around me into my films. Evergreen was a more pointed elegy to my father and the feelings he left behind for me and the other films have offered transformative views onto my family and the local environments I inhabit.

MH: Evergreen (16 minutes 2005) begins with precisely framed forest moments, the camera tilting into the light, the first roll in black and white, the second in colour. There is a luxuriant radiance that pours out of each frame, as if light were not falling onto plants, but coming up out of them. After a brief glimpse of a sunday painter, flies settle on a paint palette, the natural sound give way to machine drones, oceans beckon liners, and the first of many shipping containers marked Evergreen appear. A tree watches a plane fly past. The port appears as mouth and anus, ingesting and repelling. New houses are being built, the land fenced off and titled and sold. Is it strange to extoll the virtues of nature in an ecologically toxic, machine driven art like cinema?

RT: I made the film as an allegory paralleling my own reconciliation with the loss of my father. There is a life we observe, a life we idealize, a life we are repulsed by, and a life we live. Evergreen is about these states of living. How’s that for a generalization?

There is a wonderful complexity in the natural world that defies simplicity, I find this textural chaos visually enchanting. The act of landscape painting or photography can celebrate that diversity, turning away from human controlled designs, whether physical or temporal. The painter is as integrated within the film frame as the plant life. Her “brushes” are flower petals. Through the act of painting, she inadvertently feeds the flies. For the first moment in the film, a commerce is established—the flies feed on the art itself, leaving their tiny fly droppings on the swimming page. Concurrently the image becomes less controlled. Flower petals are caught and held in spider webs. It is at this point that the container ships enter because shipping is the lifeline of human commerce. The containers were mainly shot during the making of In Loving Memory, but they couldn’t find a home since they held too much weight as a symbol of commerce and of adult child-play. I was attracted to both their formal simplicity and their ubiquity, but also to their functional value as shells. I was further struck by their “deaths”-rusting in makeshift cemeteries in ports across the planet. What does this mean?

Moving from the fantastic world of incident that so enchants me into the world of commerce acknowledges the forces at work necessary to create the space of art in the material world. The aesthetics of commerce is facilitated by simplicity (of colour, shape, scale) and interchangeability. There are too many of us to live in the “natural” world, instead we live in a world we have chosen to make, which might be named Evergreen (as the containers are named). This modern-day fairytale imagines us everlastingly beautiful, efficient, harmonious… What is being described is the nature of artifice.

What about the death of my father? In order to come back to life, I must find a way past consolation. To do this, I assert that I am no more than a vessel containing and dispersing light and shadow.

MH: In the opening of Bliss (4:40 minutes 2006) you follow a dark grey couple with flash bulbs trailing them, then cut into quick glimpses of stained glass church windows (is God also a celebrity?). There are crazy beautiful shots of… help me, are they leaves or fire flies, turning in the wind? A bouquet of focal shifts brings us to a beach where lightning plays and people speed past. Who has time to look? This is the longest shot of the film, by far. Did you worry it would upset the temporal balance-like using too much garlic? Why the shots of the American flag, the children gathered in the park, the sudden ending?

RT: The church’s sanctuary is shown as something elaborate, beautiful, fragmented, transitory… barely real. The spinning light is caused by large flies, mayflies perhaps, circling around each other in the afternoon sun. They are nature’s parallel to that “sanctuary,” shot in super-8. Then there is a move to video: inside all is quiet, outside all is color, light, and the clamor of work and play (the children in colorful clothes) as the clouds begin to gather. The long shots on the beach let us see the approaching storm, and in the longest shot, the waterspout builds threateningly and gorgeously while passersby continue their leisured lives, unimpressed at this pending disaster. This is where politics enter, the final shot brings the funnel cloud over the darkening city, an event we are powerless to address except by watching. It is as if watching could offer a blissful refuge from the storms of the world. So I don’t worry about the length of the last beach moments, nor of the suddenness of the end—the BOMB of silence that is suggested through the cut-off.

Why the flag? It might be seen in two directions, either as a symbol of hope and unity that will endure in the face of the storm, or a pugnacious symbol of American bravado. I framed it at the bottom left of the screen to show how pathetic our (American) hubris is in denying the realities of global troubles whether they be of our making or not, a reference to a national identity that sees itself as immune to both the consequences of its own actions and the changing face of the world it has helped to create and destroy.

MH: Qualities of Stone (11 minutes 2006) is a graveyard visitation, though headstones make only a brief appearance, instead you draw attention to the natural world that surrounds them, often dripping wet in the rain. Flowers swoon into focus, macroscopic tissues of stems and branches come into view. This gives way to a series of upside down trees glimpsed as the framing adjusts. Are you filming the viewfinder of a camera? Are you looking at a look? Oh yes, there it is. A series of frames impose their view on the natural world, and then we are looking through a circular matte, as if through the scope of a gun. Shooting. Then you deliver us into a black and white world of a dream—where are we? Wind breathes life into the trees, they gesture towards us and each other before bursting into flower. Some trip.

RT: This is the third in a series on urban naturalism (following Thunder and Evergreen). I was shooting through lenses and viewfinders, interested in the effects of mediation, both on how I was acting and how I was perceiving my actions. With the super-8 camera’s diffusions in the graveyard I was hiding a bit, moving increasingly toward a crouching position as I danced among these stones feeling out my relationship to them. My “escape” from this movement (and “speech” with the graves) is found in the white-budded branches which blossom in the end, a revisitation following my discoveries.

The cut to green signals a new beginning, at once luxurious and melancholy. It is a more sharply defined sense of space, in which I start from a hiding position and move out into the light. It led to an entangling (wedding?) of plants and fence, held together in the rain. The idea of these forms sharing something was interesting to me, but so was the feel of the rain, the beautiful pearls it left on the tips of these things, catching the light just so… Moving into the dim was another retreat of a sort, feeling the love of the plants through a new kind of light and lens that finds its way into a field of other lenses-within-lenses: layers of mediation bringing their own transformations into play as I move increasingly towards interior explorations that brought the life of the glass to the fore. It was like working with living eye extensions that allowed me to release myself into a pool of vision. I thought of the lens as a seed, the viewfinder as a sister to that seed, my eye as a two-way mirror, and my hand as a kind of cultivator-of-dialogue, with both my mind and the subject-space as destinations for all of their activities. The life residing in the lens might be an extension of the self, even as we are mesmerized by its confabulations. I found these new playmates in the darkness, and through them a new perspective on the relationship between the organic and inorganic, finding myself, in the end, OUT in the full light of day.

MH: I think There (9:35 minutes 2006) is your most perfect film though I can hardly raise up a word (like a shield) towards a question. What to say about its dreamy darkness, the attention to natural shapes, the camera opening and closing its light aperture to let this abstract world breathe? Why all this edgeless beauty, the searching intervals, the seething microverse of small events?

RT: My sustained appreciation for the richness of Light developed initially in drawing media has gradually met up with my development in filmmaking. Following Qualities of Stone (which brings the process of making into the picture’s subject space) and Interplay (which is more of a dance piece humming along with the various places I inhabit), I felt a need to turn further inward and undertake a kind of Fantastic Voyage into my own lightstream-as-bloodstream. The vehicle for this was a single plant that I’d been given in gratitude. Initially I had wanted to reflect that feeling (now become my gratitude for such a marvelous gift into my dead-world office), but I quickly became lost in this light journey that the plant form was offering to me, obviated through microphotography. By looking closely, I seemed to be looking within… something. Inside the lens, the world of the plant triggered a kind of mutual dream relationship, a reflection of shapes in the mind. Was it Our mind? The mind of the plant shown through its “body language,” and my recognition of it?

As each film roll came back and was projected, I seemed to find greater connections between my emotional state and the world that was being created and recreated, as both light and darkness grew to speak with equally intriguing and, in a way, disturbing voices which both thrilled and challenged me to answer back—to further facilitate the weaving of the “tale,” a creation of this scape that seemed to mirror my own internal beanstalk worming and webbing its tangled way indeterminately through and around itself to the imagined world of giants at the top of the clouds. This is the sense with which this was edited—finding voices within the light of a newly-rediscovered world (through the camera) that gives life (the light stream reflecting the blood-or-spirit stream) a chance to breathe/flow in many directions. Of course those voices might seem my own, but I feel they are brought into being by, through, and for “others.” This is the fun I have watching this film develop its music; “listening” to these voices is a way of hearing my heartbeat, and knowing that its sound offers a way for others to beat with it, celebrating a kind of mutual spiritual mortality. This is why I (in my description of this film) call the light “seeds,” the darkness, “soil,” the movement along the path of time (both in the making and the viewing/hearing) paralleling a life’s growth, the fruits of which are these unusual discoveries of spirit. My latest excursions continue this shared path of directed discoveries.