Camera Obscura for Dreams: an interview with Midi Onodera

published in Practical Dreamers, ed. Mike Hoolboom, Coach House, 2008

I met her at the Funnel, Toronto’s avant hope and movie theatre and sometime equipment co-op. She was in charge of the gear, and was the first person I knew whose hair colour came from a bottle, the first woman I knew who was romantically attached to another woman, all those facts arrived together somehow (yes, it was a long time ago). Because I tried as hard as possible to imagine that no one else existed in the world, we didn’t speak much, but she was a reliable presence, at once equipment geek and hipster, adding a rare edge of glam to a dowdy east end haunt notable for its mirthless, uptight gatherings. So it was doubly remarkable when she left behind the narrow guage formalisms that were the unspoken code for correct practice and produced Ten Cents a Dance (Parallax), a movie which combined the structuralist motives of a previous generation with queer sexual mores.

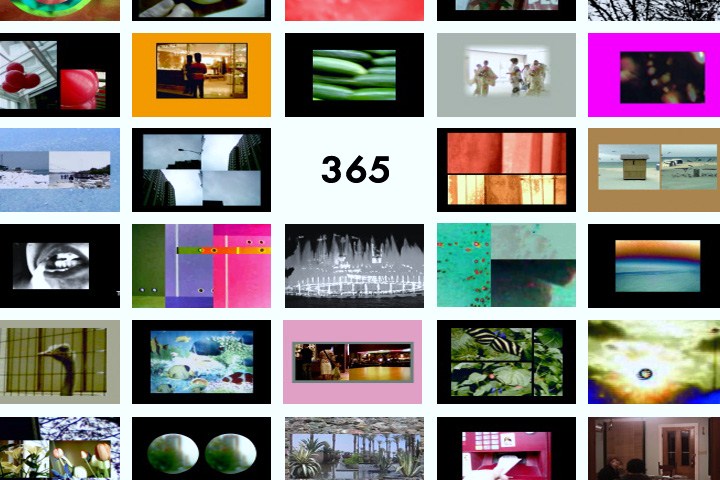

Midi has dedicated herself for more than three decades now to opening doors which look like walls to most people. She has tasted the forbidden fruit of dramatic features, celebrated the work of other artists in her own making, created a movie a day for an entire year for internet/cel phone perusals. While she is rarely in front of the camera, the surface tension and framings belong entirely to her, the light appears onscreen like a fingerprint. Her practice raises questions of living and seeing and making. How to live differently, and how to make pictures that arise out of that urgent dailiness. She has developed the knack of being able to rediscover small and familiar events in unexpected ways. She is making haste slowly.

Mike: Midi, I wonder if you could tell me about your beginnings in film. Were they an important part of your growing up? Did you enter the fray in order to change the kind of pictures which surrounded you, or to enter into that starlight? Perhaps all art begins with emulation, and variations on received wisdoms become one’s practice. But did you feel yourself in the early days of your witnessing to be outside the mainstream flow, or was the seduction intact?

Midi: I started making films in high school through a film studies class. The class mainly consisted of criticism and film theory but at the end of the semester we had a choice of making a film or writing an essay. Naturally I chose to make a film. With super-8 cameras courtesy of the Toronto Board of Education I embarked on my first film, Reality-Illusion. Although I knew very little about the technical aspects of filmmaking, I remember reading various how-to books and bugging my teacher for tips. The seven minute film was “experimental.” Although I had a vague premise of the “teenage outsider,” destruction, violence, etc. there was no clear storyline. I recall that the main character wore a long black cape and a gas mask and carried a scythe. The costume came in particularly handy since I just asked various friends to fill the role (counting on those who were skipping classes or on a smoke break). Highlights of the film included a few scenes in a Jewish cemetery, a single frame animation scene with styrofoam wig head and pyrotechnics (using the family barbecue). Unfortunately the Board of Education did not have any splicers and since I of course needed to edit my film, I set-up a system using a razor blade to cut the film after measuring off the footage with a hand-made 24fps ruler. I joined the film using scotch tape and then punched the sprocket holes out using a straight pin.

Immediately I loved the hands-on aspect of filmmaking, holding the footage up to the light and selecting my shots. It was all very primitive but fun and incredibly rewarding. My second film was a kind of homage to Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). I loved the hyperdramatic expressionistic look of the film, the exaggerated acting and otherworldliness of it all. My version, Contemplation, was a short abstract study in teenage suicide. The “actors” wore black tights and white bathing caps with white paintstick face makeup. By the time I graduated from high school I had made three films. After that there was no looking back.

Naturally I gravitated towards an arts education and although it broke my parent’s hearts (they had dreams of their daughter as a successful doctor or lawyer), I decided to go to the Ontario College of Art. At that time, in the late 70s, there were very few Asian students at OCA, let alone of Japanese descent. I recall two other Asian students in my class, both determined to pursue a career in graphic design. I too was influenced by the commercial tide and had aspirations to become a fashion designer. I knew nothing of contemporary experimental film and never imagined I could actually survive as an independent filmmaker.

Gradually through my film studies classes at the college, my knowledge of cinema increased as did my filmography. The main stumbling block that I faced in those days was the technology. It was a challenge to successfully create what I saw in my mind and realize it in film. Feminism was the buzz word of the day, but somehow most of the male film and video (technical) instructors hadn’t heard it. Luckily my parents gave me a super-8 camera for my seventeenth birthday and this gave me tremendous freedom. Gradually I purchased my own super-8 editor and splicer, and guided by my dog-eared copy of Independent Filmmaking by Lenny Lipton I eventually worked through the mechanics of super-8 filmmaking. Throughout OCA I continued to make films, alongside painting and photography. By the time I graduated I had made eleven more films. All of the work was shot in super-8 and with the exception of one film, remained in the super-8 format. I learned how to optically print film because I wanted to include subtitles in a piece I was working on and eventually I started to use the optical printer to manipulate super-8 original and blow it up to 16mm.

There is no question that in the 1980s the worlds of film and video were universes apart and from the beginning I fell into the film camp. Although I was exposed to many video artists’ work, I always felt visual explorations in video were limiting and the technology overly complicated. I love the romance of sitting in a dark theatre and falling into the world of film—the flickering of the projector light, the mechanical hum coming from the back of the room, the magic unfolding on screen. Even the technical language of film seems to be more lyrical than video—the legend of MOS—”mit out sound” or “without sound” spoken in a German accent; answer prints, reversal film stock, etc. Compared with the clinical and sometimes sexualized language of video: female to male connectors, “lesbian” connectors, BNC, etc.

As far as the mainstream aspects of cinema, I never felt that I wanted to make a Hollywood-type drama. I was so drawn to the work of avant-garde filmmakers such as Joyce Wieland, Maya Deren, Man Ray, Dali and especially Kenneth Anger that I actually didn’t even go to the regular movie theatre very much while I was at school. Perhaps it was my punk, feminist, Japanese background that made me feel like I could have a voice in experimental film. I could express myself on my terms rather than conform to mainstream expectations of cinematic representation. But even within the haven of experimental film there were remnants of the 1970s presence of structuralism—the endless viewings of work by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, Hollis Frampton. I tried to like the work, really I did. It just never touched me.

Mike: When I met you in the early 1980s you had been hired to be the equipment guide and technical director (what was the exact title again?) at the Funnel, a now defunct fringe movie showcase that aspired to vertical integration. There were twice weekly screenings, equipment for hire on the cheap (for members at least), and a modest distribution program. What drew you to the Funnel and why did you stay there?

Midi: Although I graduated from art school in 1983, my exposure to the Funnel began around 1980. At the time, experimental filmmaker Ross McLaren was one of my teachers. Besides showing various classic and current experimental film works, he tried to expose us to the world beyond school. This of course included a field trip to the Funnel. Located in the industrial edge of King Street East, the Funnel was THE centre for exhibition, distribution and production of experimental/artist-based films. I believe filmmaker Anna Gronau was the director around that time. To me, the Funnel was the centre of the universe. It was the coolest place in the city and somewhere you could go and immerse yourself in experimental film. I recall thinking that it would be amazing to show my films there, never mind that it was a small theatre (one hundred seats?), away from the rest of the Queen Street art scene, and freezing in the winter and boiling in the summer. I recall seeing Kenneth Anger and Ondine as a student, which was on par with meeting the Sex Pistols.

I got my wish and did indeed show many of my early works at the Funnel, first through student shows and later as a practicing artist. My first non-student screening took place in 1982 in a series called “Formal Film by Women” curated by Anna Gronau. That particular evening included a film by Joyce Wieland, another one of my role models. I couldn’t have been more thrilled. I recall speaking with Joyce after the screening and was touched by her warmth and generosity. Later, I got to know Joyce a bit better as I worked on restoring some of her old film prints.

When I look back on the early 80s now, I realize that many of the screenings I had took place within a feminist context. Some of my early exhibitions (photography and text pieces) and screenings were part of the International Women’s Day Conferences, and benefits for various lesbian and feminist publications. There seemed to be so much going on within the feminist community and in the world of experimental film.

Being an artist-run centre, the Funnel was on a tight budget and couldn’t afford to hire new staff unless it was through a government sponsored program. But as a recent grad, I knew I wanted to work there and start my life as an artist. Through a program called “Futures” I was hired as the equipment coordinator and paid the grand sum of $150 per week. Needless to say I was barely able to survive, living mostly on Jamaican beef patties, popcorn and soup. My job consisted of checking all the equipment, keeping it in running order, orienting members on all the equipment at the Funnel, organizing workshops and assisting with the biweekly screenings. It was one of the best jobs I’ve ever had. I worked first under the leadership of filmmaker and Funnel Director Michaelle McLean and with the great help and patience of Villem Teder, a fellow filmmaker, Funnel member and techno-whiz, learnt how to solder, make seamless reel changes and load the ancient 16mm Frezzolini camera. I worked during the day at my job and then would stay on late into the night working on my own films, using the equipment free of charge. During my years at the Funnel from 1984-1986 I met and hopefully assisted probably every artist who was working in film in Toronto at that time.

Mike: Going twice a week to the Funnel, hardly managing to say a word (like church, silently raising eyes up to the light) I held the preposterous belief that watching these difficult movies would imbue the viewer (magically, like fairy dust) with a high moral intelligence. Nothing in the organization bore this out, though I was undeterred by examples, I imagined that these fringe movies were nothing less than the thin edge of a social revolution that would one day empty out the other theatres. Did you imagine (was it only me?) that these movies possessed a larger social/political purpose? Would ‘changing the image’ mean that life outside the image would also, must also, change?

Midi: Briefly before I got the job at the Funnel, my brother got me a job working in a custom colour photography lab just a few steps away. It was my first real taste of working in a “corporation.” I had put myself through school working as a cook at various restaurants in the city but never worked in a company per se. I hated my job. I was the minimum wage, low-life hired to collect people’s orders, check and package them for pick-up or shipping. 9-5, thirty minutes for lunch. My boss was a single mom who seemed to be searching endlessly for a “cabbage patch” doll for her daughter. She had nothing but contempt for those around her and made my short life there miserable. After work I would go over to the Funnel and hang out, my oasis of normalcy. I tell you this story because I think that it influenced my concept of “changing the world.” I realized that the mainstream, those clamoring for “cabbage patch” dolls and commuting from the burbs, was not an audience I had any hope in reaching. I didn’t believe that anything like “experimental” film could ever change their daily lives. My audience seemed grounded in those regulars who attended Funnel screenings.

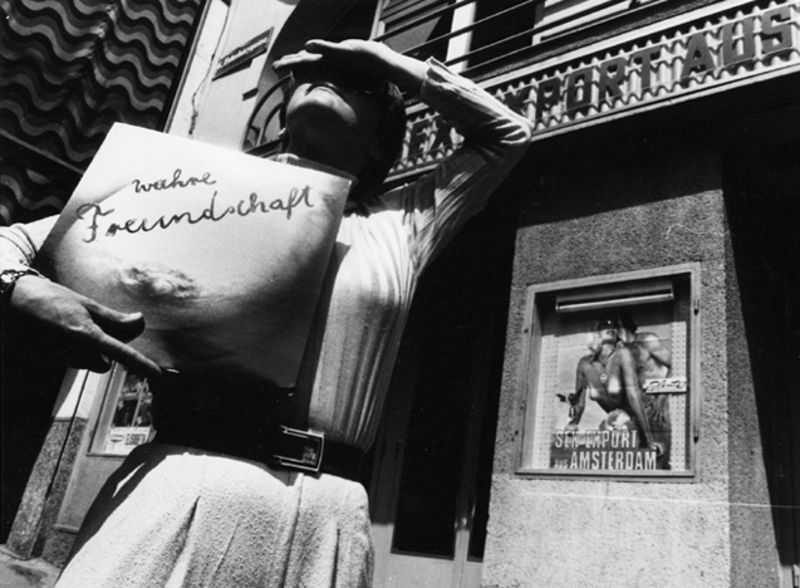

The 80s was an exciting time. I felt the rawness and tension of the feminist movement, the debates around women-only events and spaces, the constant conflicts about pornography and censorship; the dying flames of the punk movement, its commercial morphing into new wave; the rapid growth of lesbian and gay culture through the beginnings of lesbian and gay film festivals; the embryonic development of “multiculturalism.” But these events and communities were completely separate from each other and any kind of cross-over was usually viewed with suspicion. How could I love punk and call myself a feminist? The gay and lesbian movement at that time was predominantly white and issues of race hardly ever entered into discussions of equality and the reverse was the same for various ethnic communities.

Art, film, personal practice was the glue that held my life together. Without it I think I would have gone mad. In some ways I never felt that I could truthfully be myself in any of the politically charged communities, except at the Funnel. At first I believed that I had found my home, a community of like-minded people. But in the end, the utopian world I thought I had found didn’t really exist. It’s difficult to explain: it’s not that I faced distinct and direct racism, homophobia and sexism. It’s just that there was this undercurrent of tension, this off-kilter feeling that I was intruding, that I didn’t really belong.

As I gained more exposure to the growing number of films being made by women, my confidence grew and I felt more and more that I could embrace what naturally came to me, story telling. This discovery was completely empowering. Finally with the rise of “new narrative” I saw that stories could be created outside of a Hollywood framework. To this day, when I think of some of the early films by Chantal Akerman, Chris Marker, Valie Export and some of the New York underground scene, I can still see shadows of their influence in my current work.

But as much as I found these works energizing and provocative, I think that they helped to create a kind of creative divide amongst the Funnel membership. As some of the women embraced this infusion of narrative, some of the men resisted this “trend,” staunchly defended structuralism and tried to preserve their perceived role as dominant “experimental filmmakers” in the city. For me this aesthetic/political/theoretical split finally took its toll when I started to make The Displaced View.

Michaelle McLean was one of my producers for the film and besides the obvious route of arts council funding, we decided that we needed to source alternative methods of funding. One of our first thoughts was having the Funnel sponsor the film so we could collect donations in exchange for a charitable receipt (since the Funnel was a registered charity). Michaelle presented our proposal to the Board which was rejected, on the grounds that my film was not “experimental.”

I guess to go back to your original question about “changing the image” and its possible impact on “changing life outside the image,” well, from my experiences, I did see change occur within the genre of experimental film: changes that took place on the screen, in terms of feminist content, representation, narrative exploration, etc. Off screen, in life, those changes were also present. More women were making films, learning the technical foundations of production, developing their own voices. But naturally there was resistance to change. The rejection and labeling of my film as “not experimental” seemed incredibly narrow-minded and rooted in a dying aesthetic. I did not subscribe to the idea that “experimental” film had to be “difficult” or “obscure.” I was interested in exploring the technical aspects of film as they related to the content. I saw that different genres were all part of the same family. It was through the exploration and employment of different techniques and styles, the dismantling of cinematic stereotypes and construction of a unique world that had the ability to transform a work from “traditional” to “avant-garde,” from mediocre to amazing. I saw the label “experimental” as something created by the old boys’ network. Something so prescribed that it sometimes became mind-numbingly painful to watch. So rigid in form and technique that it was turning in on itself.

Looking back at the Funnel, I clearly recall that in all my years going to screenings, working the job, hanging out, I only met one other Asian-Canadian filmmaker, Keith Lock. But although he kindly loaned us his 16mm moviola, he was rarely around. I don’t recall ever meeting another Asian-Canadian woman or come to think of it, anyone of colour. As far as lesbian “experimental” filmmakers at the time, there was Barbara Hammer. It’s not that I needed role models, but there was so much of myself that I felt I had to “keep under wraps.” That’s not to say that I thought the lesbian/gay communities and the Asian-Canadian communities would be more welcoming. On the contrary, those communities had and in some ways still have expectations about work produced by “their artists.”

Mike: The first story I heard about famed New York underground legend Jack Smith in relation to the Funnel was that he had been invited to show Flaming Creatures, a movie many of us were eager to see, and which had been banned by the provincial censor board years ago. The story goes that he had showed up at customs with a print of Flaming Creatures attached to his wrist with jewel encrusted handcuffs. The jewels were dime store glass of course, and when he refused to open the case customs refused him entry. Perhaps this was another one of the apocryphal stories that circulated around someone who seemed both smaller and larger than life. The Funnel paid for another flight which brought him into town for a weeklong performance in 1984, and there are two indelible moments that remain for me. On “opening night,” about an hour after the announced start time, with Jack still shuffling around tweaking the position of the furniture and disappearing backstage for long stretches and very occasionally putting on a record, Phil Hoffman turned me to and said, “I think this is it.” We were all waiting for it to start, but this waiting was the play itself. The second moment occurred three nights later, there were only four or five in the theatre and I had come a bit late, only to find Jack at the door, crying because there were so few. That was so touching and raw and beautiful. You made a movie of these events, called A Performance by Jack Smith (5 minutes 1984-92). Given his notorious “difficulties” with people, I’m surprised you were able to film at all. Can you describe your interactions with the maestro and how the movie came to light?

Midi: Jack Smith. My memory might not be that good, but I’ve never heard the jewel-encrusted handcuff story. The truth is far less colourful. You are right, Jack was originally invited to screen Flaming Creatures. This was to be the first screening of the classic film in Canada. We were all terribly excited and like schoolchildren anticipating the final bell on the last day of school before summer holidays, we all waited for his arrival. I recall that for some reason then Funnel Director David McIntosh and I were playing endless card games, after regular Funnel hours, waiting to hear that Jack had arrived. I guess because none of us had access to a car, no one actually met him at the airport. The clock kept ticking and we kept waiting. Yes, his plane had arrived but he wasn’t on it. David reached him at home in New York. He had missed his flight and was in the middle of getting rid of all the hard angles in his apartment, it was a major plastering job. After David spoke to him (at length) it turned out that Jack didn’t want to bring Flaming Creatures up to Canada, he was afraid of crossing the border with the film. Finally he agreed to come and do a series of performance nights. David arranged for another ticket and we took up our second night of waiting.

When Jack arrived it was my job to arrange any technical requirements he had for the performance. I had been used to dealing with all kinds of equipment requests but wasn’t prepared to find a chez lounge. Thankfully David took care of that but in the end we had to purchase it since it went through a lot of wear and tear during the week. Your description of the performance is fairly accurate. Overall the performance grew over the week and involved not only Jack but other Funnel members and fans who participated in sewing various “brassieres,” some perched on ladders, others floating around the stage. The audiences were never full and most people wandered in and out, like yourself, unsure what to make of it all. I worked most of the week in the projection booth occasionally putting on a record that Jack had brought with him and I suppose other technical things, which were minimal at best. As a kind of “off stage” performance component, there were several Funnel members rushing around taking photos and shooting film. I admit, I was one of them. But instead of being at the front of the stage, I set my super-8 camera up in the booth, shooting time lapse.

For me the whole thing was a bit of a let down. At that time in my life I hadn’t seen very much performance art and didn’t feel I understood the language well enough to critique it. Meeting Jack on the other hand, was absurdly fun. He was rather a quiet guy, with tremendous energy that he always seemed to keep in reserve. There is no doubt that he was slightly paranoid (although I can see that some of it was justified) and he was a master at creating something out of nothing.

Later, after the week long adventure was over, I heard that Jack had absconded with all the photos and film footage that was shot by the other Funnel members. Later still I heard that Jack exhibited the work and called it his own. The only reason my footage remained a secret was because he never knew I was also filming. I had the footage stored away for years, more as a personal record of the event than anything. But after Jack died I thought it was time to share it with others. The footage was shot in 1984 and finally released as A Performance by Jack Smith in 1992.

Jack touched so many people that week in Toronto, that I am sure that there are a million different stories. It would interesting to hear what other people at that time experienced. There are probably still hidden treasures, like photographs and audio recordings of that time.

Mike: Ten Cents a Dance (Parallax) (30 minutes 1985) remains a touchstone fringe movie on many counts. Its frank sexuality was especially striking in a climate where the provincial censor board was actively banning movies and shutting down art spaces. Could you describe the film’s making — were all three sections made at the same time?

Midi: I received my first Ontario Arts Council grant for Ten Cents A Dance (Parallax). I think I got $2000 which was not a lot even back in 1984. It was however a vote of confidence from a jury of peers and money that I would never dream of having otherwise. The film was originally proposed as a vehicle to deal with issues of communication. I wanted to try and illustrate the idea that communication between two people, regardless of sexual orientation, contains unspoken truths and underlying meanings. The grant application conjured images of a blocked writer sitting in front of typewriter, the persistent hum of the electric typewriter taunting the artist. Now that I think about it, the proposal was probably pretty weak, so I am thankful for the small grant.

I recall early on that I wanted to make the film as a double screen projection. I was quite influenced by Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls (1966), Forty Deuce by Paul Morrissey (1982) and John Massey’s three projector installation As The Hammer Strikes (A Partial Illustration) (1984). John Massey’s work especially impressed me, since I was the equipment coordinator at the Funnel I assisted him with the premiere of this work. He had specially built three 16mm projectors which ran in sync. I remember that there was a main power switch for the set-up which reminded me of a Frankenstein movie. It was extremely loud when it ran and John was very tense during the entire presentation because if there was a break in the film then all three film prints had to be checked to insure they were back in sync. We talked about how he constructed the whole thing, how expensive it was, etc. To save on money I decided that I would build a dual projection system from second hand machines sold off at government auctions. But I guess I am digressing.

How did I make it? Hmmm, as I said I wanted to comment on “unspoken” or “between the lines” communication. I really have no clear recollection how I actually progressed from shots of typewriters and “communication tools” (my original thought) to one night stands and sexual encounters. But when I hit upon it, it struck me that the situation of a one night stand personified the difficulties of communication.

I knew that I wanted to shoot in 16mm with two cameras. I had never really done any work with “actors” and didn’t have a clue about directing in a conventional sense. I decided that instead of using real actors I was pretty much at the mercy of people I knew or friends of friends. I worked out of the place where I was living at the time and decided to shoot over a few weekends. Everyone either worked for free or a few hundred dollars. We had great food and beer. But like directing “actors,” script writing was beyond me. I decided that I would choose “characters” who had a dramatic flair about them and just ask them to play themselves. There would be three scenes (although I didn’t really know what they would be).

The first pair I decided on were acquaintances: two women who had a kind of S/M relationship which manifested itself as a twisted mother/daughter bond with a co-dependent addiction to Buckley’s cough syrup. I was almost terrified of them and their eccentricities but very much wanted them to be in the film. That first shooting day, I remember they asked to have two white sheets erected in front of the cameras (which were side by side). Relying completely on their improv talent (so I hoped) I put up the sheets, told them they had ten minutes (roughly a 400 foot roll of film) and started shooting. As the minutes dragged on and I saw the money I had spent on the day waste away, I kept hoping the sheets would drop revealing something, anything, other than a white sheet. After what seemed like hours, we heard the film run out of the cameras, but of course, the sheets never dropped. The women were completely stoned on cough syrup and who knows what else, so they thought their performance was amazing. As I worked with the rest of the crew to wrap up for the day, I just felt sick. I had wasted two rolls of film, didn’t have even the beginnings of a film and thought that I would never be able to direct people on camera.

After a few weeks of moping around, trying to figure out where to go next, I decided on a few things. 1. I would really have to take more of an active roll in conceiving, shaping and directing the scenes. 2. There could be no more costly mistakes or else I would never make the film. I had already gone through my contingency, and I could only afford six more rolls of film and that was it. (As it was, David McIntosh helped me to secure a deal with the old original PFA lab. He called the owner of the company for me and asked if I could get a discount on processing. He got me fifty percent off! I was thrilled.) 3. I would have three scenes: a gay, a lesbian and a straight encounter, each of them involved in either a sexual encounter or negotiating a one night stand.

As I continued to struggle with the actual content, I came across ads for phone sex in the relatively new, free Toronto weekly, NOW Magazine, but all the phone numbers were based in the US. I decided to cast Ross McLaren, my old OCA experimental film teacher and through David, I met artist, Wendy Coad. One night we all got together and with the help of Ross’ credit card made a collect call to one of the phone sex places in Buffalo. We recorded the conversation, Ross on one line, Wendy and I, barely containing our laughter, on the extension. After the brief ten minute call was over, I gave the tape to Wendy to memorize. This was the script. A week or two later, we shot the scene. One camera was downstairs in the basement and the other was upstairs. I operated the camera focused on Wendy downstairs while David Bennell shot Ross upstairs. We rehearsed a number of times—it had to be perfect. Both Wendy and Ross were terrific, each of them adding little touches as we reworked the scene. Finally as the day was turning into evening, we shot.

For the “lesbian” scene I searched high and low for someone to play the roles, but couldn’t find the right people. The script was derived from an actual dinner conversation/improv I had with my girlfriend at the time. I recorded the “Japanese restaurant” soundtrack at a real Japanese restaurant while I was on a date with another woman. Finally desperate to cast the roles, I asked Anna Gronau to help me out. Surprisingly Anna agreed. Again, over a weekend, we rehearsed and drank sake until we felt we could do it perfectly. The whole thing was much harder than I had anticipated. The timing was critical since we had to sum it all up before the film ran out of the camera. The cameras, like the doomed sheet scene, were side by side. David B was setting them up and he called me over to look though the lens. He had overlapped the frames slightly—it was perfect, parallax!

The final scene was done with the grateful participation of David MacIntosh and John Goodwin. Inspired by the 1985 St. Catherines public washroom bust which had occurred a few months prior to our filming, we shot the film at the Funnel. The St. Catherines raid had a tremendous impact, not only on that community but nation-wide since the men who had been arrested for public washroom sex had their names published in the national newspaper. As a result one of the men committed suicide. We chose the Funnel since it was free and the men’s washroom was so rundown we doubted anyone would notice if we carved a glory hole between the stalls. Once again, it was all shot in one take. (A few days after we shot in the washroom there were metal plates covering our glory holes! In a building where nothing ever seemed to get fixed, it was astonishing.)

The situation of a “one night stand” ideally personifies the difficulties of communication, as well as generating mixed emotions, risk, excitement. Overall I had the sense that certain sexual activities were at the time very foreign to a film audience. The first scene was at my instigation. I thought that most lesbians had had the experience of either being approached by a straight woman who was curious, but I had yet to see this negotiation take place on the screen. Similarly the third scene of the film involved phone sex, a relatively unexplored topic.

Mike: Did you feel that it was important to be in the movie yourself?

Midi: It happened more by default and it was only afterwards, when critics started writing about the film, that it became an issue of representation of an Asian-Canadian woman, and a mixed race relationship.

Mike: The toilet cubicle sex scene, filmed from above, is a riff on the surveillance cameras Ontario police had been using. Did the question of safe sex come up at all? Do you feel responsible to the queer community in terms of producing pictures which represent “healthy” sexual practices?

Midi: In 1985, in Toronto, the issue of safe sex was just beginning to make an impact on the community. In places like San Francisco where there was a large gay community, safe sex was a very hot topic and this is where some of the initial negative reaction centered.

Back in 1985, four years after the US Centers for Disease Control published its famous report describing the deaths of five gay men in LA from a rare form of pneumonia, there was panic in the gay and lesbian communities. People just didn’t know the extent of the disease. Now 25 years later and over 25 million deaths and counting, I think that there is no question that if I made the same film today, safe sex would be automatically included in the film.

Mike: Finally, I wonder if you write about the reaction you had when presenting the movie, particularly the “riot” during the Frameline Festival at the Roxie Theatre in San Francisco.

Midi: This is a major question. Ten Cents was made at a time when Lesbian and Gay Film festivals were still finding their way. They were dealing with issues of representation, definitions of what makes a film “lesbian” or “gay”, and issues of including or excluding work done by marginalized filmmakers within the community (ie. most films made around that time were made by white men). Super-8 seemed to be the cheap format of choice for the economically struggling dyke and there were very few works being made by queers of colour.

The riot that you speak of took place during the 1986 San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. Ten Cents was programmed in two separate short film evenings. The first screening that took place was called “Four from the Commonwealth.” As odd as it sounds today, my film, representing the commonwealth of Canada, was shown with other short films from New Zealand, Australia and Britain. This screening took place without incident.

Because of the perceived lack of lesbian works in that year’s festival, the film was also programmed in an evening called “Lesbian Shorts.” I did not attend the festival but was told afterwards by the Festival Director, Michael Lumpkin, that my film caused a riot to break out in the audience.

The reasons for the audience reaction were mainly focused on the issue or definition of what makes a film a “lesbian film.” Does the maker of the work need to be a lesbian? Does the subject matter she chooses to explore have to be a “lesbian specific” subject? Can a lesbian portray other sexualities in a film and still make a “lesbian film”? These questions, combined with the lack of lesbian-oriented work in the festival, and the ongoing tensions between the gay and lesbian communities, all contributed to this reaction.

Although I had screened Ten Cents at other mainstream festivals, San Francisco was one of the first Lesbian and Gay festivals to pick it up. I had no control over how it was programmed and didn’t have a clue about the brewing anger from the local SF lesbian community. I knew the film was controversial from the beginning but had no idea that it would be a match on the firewood.

I remember talking to Anna at length about the growing number of film festivals that were specifically lesbian and gay or women’s film festivals. I hated the idea that my work would only be accepted and shown within (what I saw as) these social ghettos. Yes, I am a lesbian, a woman, of colour, etc. but I just didn’t and still don’t subscribe to this programming agenda. I see my work as extending beyond these classifications. I want the work to be seen by as many different people as possible within an independent context. For me it’s about finding the connections between marginalized groups, drawing people from differing backgrounds together not separating them further and isolating them. It’s about breaking down the walls that separate us, not creating them.

As far as SF goes, what the “riot” did for the community was to open up a dialogue with the Festival Board of Directors and the lesbian and gay communities in the city. I don’t know if it caused the Festival organizers/programmers to become more sensitive to work produced by lesbians and women of colour, but I think it opened their eyes to a number of debates and issues. Sometimes I wish that these discussions would take place more in the different community-oriented festivals today. We, both as makers and audience members, have become far too complacent in our expectations and definitions of what a particular film should do or represent.

Mike: In an essay called Centre the Margins, Richard Fung talks about the absence of gay Asians on movie screens, and cites your The Displaced View (52 minutes 1988) as a notable exception. He goes on to write: “In my own video work in the area, I have seen the most important task as the representation of gay and lesbian Asians as subjects, both on the screen and especially as the viewer. I believe that it is imperative to start with a clear idea about audience. This in turn shapes the content of the piece.” Do you feel the same, do you begin your work with a clear idea of the audience, and the political arena your work is entering into? Do you feel the responsibility which is implied in Richard’s remarks about his own work, and does it similarly shape the form and content of your work?

Midi: Ideas for The Displaced View developed while I was in art school. One of my teachers was Morris Wolfe, who taught a number of classes in film criticism and theory. He was extremely encouraging and through his screenings and commentary I saw films from around the globe that embraced a kind of cultural specificity and delicacy that I wanted to convey in my own work. Morris encouraged me to look into my history, my cultural and familial relationship with the Japanese-Canadian community. I wrote a personal history piece narrating the conflicting views of three generations of Japanese-Canadians based mostly on my family history. This piece was later published in Fuse magazine and was the beginning of The Displaced View.

When I began work on the film, I decided immediately that my primary audience would be the Japanese-Canadian communities. Within that community my priority viewer would be the Issei, first generation JC. I felt that this generation, my grandmother’s, was dying out and it was important for me to convey their story in their language. I felt that the gay and lesbian audience would not be interested in the work since it did not deal directly with issues of sexuality.

In Richard’s paper he talks about the importance and scarcity of films and videos which represent lesbian and gay Asians. With The Displaced View I never saw my audience as lesbian and gay Asians. Perhaps this was due to the fact that back in the 1980s I had only met one other Japanese-Canadian lesbian. I was not active within the JC community, which was predominantly heterosexual while the lesbian communities in Toronto that I had come across were predominantly white.

Politically I did not realize the terrain I would be traveling would be so charged. Naïvely I believed that my work was more culturally charged than politically. Although I realized that my film would be the third film made in Canada by a JC about the internment, I honestly thought that I was storytelling, not making a political statement. (The first film was made by Jesse Nishihata Watari Dori: A Bird of Passage back in 1972, the second film, Clouds (1985) by Fumiko Kiyooka and Scott Haynes).

My motivations have never been solely politically driven. I am not a documentary filmmaker, I am interested in stories, the construction of identity, memory, personal history. I am not a political activist though I do inject my personal political views into the work. But just because I don’t personally impose a political framework does not mean that others (audiences, funders, etc) follow suit.

Like the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Film Festival audience reaction, audiences in marginalized communities have enormous expectations about work produced by artists who they believe represent their communities. In 1988, when The Displaced View was launched, it was invited to a few lesbian and gay film festivals, based on my reputation with Ten Cents A Dance. For the most part, I think that lesbian and gay audiences were disappointed. It was not the sexually charged follow-up to Ten Cents that people expected. In fact the lesbian content is minor, some would argue non-existent. Most lesbian and gay audiences didn’t even consider it to be a “lesbian film” nor one that was suitable for that specific audience. On the other hand, within the mainstream festival world the film got substantial play at international film festivals to mixed audiences-straight, gay, mixed races, etc. As far as Asian-specific festivals, there were far fewer back in those days, but overall I recall a positive reaction although for the most part it was classified as a documentary—but that’s another issue.

I think that if I were naturally a more socially-driven person, I might feel more political responsibility for my work. Perhaps if I had to rely more on my subjects to tell a story, as in documentary practice, I would feel the community pressure more intensely. But my favourite way of working is in solitude. I want to shape the work according to the material, the shot, the sound, the rhythm of the sequence, not around political motivations.

Mike: In The Displaced View you take up the issue of Japanese internment during the second world war via a portrait of your born-in-Japan grandmother. In voice-over you say, “You only talk about what you want and don’t remember the bad.” She is very reluctant to speak about what happened to her, so your historical/reclamation project circles around its subject, looking for a way forward. Was her reticence frustrating for you?

Midi: By the sound of your question, it appears that you’re viewing the film as a documentary. In fact it’s a construction, a collection of truths or stories that have been assembled into a structure describing three generations of Japanese-Canadian women. Although all the stories and details in the film are true, they didn’t all happen to my family or a real family. I hired someone to conduct audio interviews across Canada with women from three generations (Issei, Nisei, Sansei) and got them to share their wartime stories with the Sansei generation. I did so for several reasons: I needed to collect stories to build on, rather than simply rely on my family’s history. Many JC families had never told their children or grandchildren about their experiences, so it became an oral history project, something that each family could build on as a personal archive. The reluctance to discuss this history was of course locked in the horror, disenfranchisement and demoralization caused by the internment. Naturally I started with my parents and grandmother’s stories, but they were so different I started to wonder how to tell such conflicting truths or whether these differences existed only within my own family? When I played those audio interviews I heard the same shock and dismay from the Sansei women. I felt their sense of a lost culture and an almost forgotten history. It was therefore critical for me to tell as many stories as I could, making a screen family rather than rely on the truth of one or two memories.

So when you mention the “grandmother” character, (played in the film by my own grandmother who was already in her late 90s when we shot) I have to smile. She was actually reading a translated script. I wrote the script based on some of her experiences and the experiences of others and then my translator, Tomoko Makabe created the Japanese text and together we worked with her on her “performance.” There is one moment in the film where she suddenly goes off the script and starts to question her memory of the events, it was so spontaneous and in character that I left it in.

All the scripted voice-overs are archetypes. They represent three generations of conflicting thoughts and stories, three different voices with varying degrees of “ethnicity,” colouring the viewer’s impressions. For this reason, the tone and text of the voices was very important. For instance, the voice that represents the “mom” character is not my mother at all, but someone I hired to perform the role. I needed a voice that was more heavily accented with Japanese and although my mother attempted her best Japanese accent, she unfortunately did not get the role, although she does appear in the film visually.

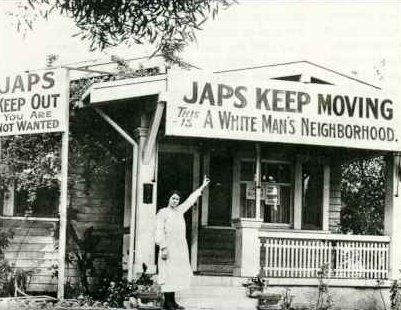

Mike: During the second world war, in a political gesture that echoed the Americans, the Canadian government rounded up its own citizens, those of Japanese descent, and without trial or recourse of any kind, forcibly removed them from their homes and put them into camps. How did you find about the internment?

Midi: I think almost every child explores the books that rest on the shelves of their childhood home. For me, it was a book called A Child In Prison Camp by Shizuye Takashima (1971) that first made me aware of the internment. The book, a rarity of sorts, was full of watercolour paintings by the artist/author; the story told of her time spent in one of the BC camps from the age of eleven to fourteen. I don’t believe that I actually read the book from cover to cover, but it was the paintings that drew me in and kept bringing me closer to imagining my parents when they were younger.

Mike: Why does your grandmother say that she has no regrets coming to Canada, even though she was taken from her home and put in a camp?

Midi: My grandmother came to Canada in the 1920s and like many others who arrived back then, life was most difficult back in their homelands. War, poverty, hunger and little hope of a future led these people to the “land paved with gold.” America and Canada were the new frontier just as it still is today for some people. I imagine that before WW II, many immigrants did not expect to be treated kindly by their adopted country. But for whatever reason they could not return to their place of birth and instead learned to live with intolerance and discrimination. Most people of my grandmother’s generation developed a strong sense of pride for their new homeland. But as the generations get further away from that first generation of New Canadians, we find it difficult to believe that life could have been worse in their birth country.

Mike: Were there a lot of other voices speaking out about internment when you were making your film?

Midi: Although the issue of redress was one that had been brought up in a personal lawsuit against the Federal government as early as 1969, it wasn’t until the 1980s that the community actively and vocally started negotiations with the federal government. I didn’t have much to do with the many community meetings and discussions that were taking place—most of the talk centered on compensation and political work, but I was interested in the personal stories. It wasn’t until I approached the Federal department, “Multiculturalism Canada” under the Secretary of State for production funding in 1985 that I was exposed to the political nature of my film. The project was initially rejected due to a funding freeze, then as I continued to inquire about the possibilities of future funding, I was told by the office that any proposal dealing with Japanese-Canadian history was perceived politically and that since the Japanese-Canadian community was currently in negotiations with the government, any support of my project would be perceived as support for the entire community and that the Federal government was not prepared to do so at this time. Finally after a continued battle with Multiculturalism Canada, I received funding for the film in 1987, shortly before the government announced that they had reached a settlement with the Japanese-Canadian community.

Mike: Could you elaborate on this statement you make in the film in voice-over: “To fight for my sexuality I ended up protecting my culture.” Did you feel you were “coming out as a Japanese woman” with this movie?

Midi: Up until the making of this film I had pretty much ignored my “Japaneseness.” As an adult I didn’t have any Asian friends nor was I involved in any Japanese-Canadian community activities. Up until that point I was concentrating on honing my craft and skill as an artist filmmaker. I felt that the JC community in general and my parents’ generation in particular, was conservative and rather narrow-minded. Because I had already made Ten Cents A Dance I felt my radical views and lifestyle would not be accepted. To answer this question properly one could write an entire book on homophobia within cultural/ethnic minority communities. But in short, I felt that I didn’t belong in what I perceived as the Japanese-Canadian community. Most of my Sansei (third generation) peers had been encouraged by their parents (in part because of their wartime experiences) to become doctors, lawyers, accountants and business people. There were very few artists in the JC communities across Canada period, never mind a lesbian artist/filmmaker.

Originally I had no intension of even mentioning my sexuality in the film. I wanted to concentrate on my “Japanese” side and felt that it might alienate the JC communities I was trying to reach. But the more I worked on the script and tried to make some sense of what had happened to my parents and grandparents, I could only compare it to my struggle for equality and recognition as a lesbian. Once I made this connection, I could more clearly picture the struggle that went on for the Japanese-Canadian and American communities. I felt that one line suddenly refocused the film in a different way and brought together these different, yet similar struggles against discrimination and prejudice.

Mike: There are many evocations of “Japan” in your film, from the drummers to rice makers to Japanese landscapes. The central image of the country which endured for me were the shots of you sitting on a train, with the window admitting moments of passing landscape-the outside looks like a movie passing by on the other side of the glass, remote and untouchable. Could you talk about your choices of how to create a picture of Japan and Japanese culture?

Mike: The film was shot entirely in Canada. I didn’t go to Japan to shoot any of it. I used images that were familiar from my childhood or those I thought illustrated a cross-generational bond. The images of mochi-making or rice pounding was a recreation from my youth (I actually shot it in the gymnasium of the church that I went to as a child). The scenes with the Japanese dancing, tea ceremony, shrine raising, etc. were all shot at the Powell Street festival-the annual mid-summer celebration of Asian Canadian arts, history and culture in Vancouver. These images of “Japanese-Canadian culture” are different from images of Japan, these images are a fabrication of “Japaneseness.” They are traces of an old Japan that no longer exists in the contemporary world. The “Japanese” elements in my film are more reminiscent of a Japan that my grandmother’s generation left when she came to Canada. Like most immigrant communities this kind of attachment or recollection of their past lives and memories are like a generational marker captured in aspic. These markers become cultural touchstones for the preceding generations, until these memories, traditions, and rituals are replaced by a new wave of immigrants and their children.

Mike: You make a lovely and radical choice by refusing to translate your grandmother’s Japanese voice-over. Can you talk about this decision?

Midi: I made The Displaced View primarily for the Issei generation. Since most of that generation continued to speak Japanese long after their arrival to Canada, translation was part of the project from the very beginning. I had noticed, like many immigrants, that the Japanese language my grandmother’s generation spoke was beginning to disappear as that generation died. Like their memories of Japan and Japanese culture, their language was also trapped in time. Some of the words and slang of their day simply weren’t used in modern Japanese. I knew that once that generation had gone, all traces of their language would die with them. I wanted to try and preserve it, but at the same time I was aware that some of my audience would be like me, Sansei, unable to speak or understand Japanese. So I decided to use language as an element that would play a dual purpose: 1) to directly address and privilege the Japanese-speaking audience 2) to place the non-Japanese speaking audience in my position—someone who does not understand the language. The latter point was taken further in my decision not to have an English translation. I wanted the non-Japanese speaking audience to experience the Japanese language the way I did as a child, without direct translation. To this day, my relationship to the Japanese language rests on my memories of listening to my grandmother speak Japanese. I listened to the intonation of her voice, the rhythm of her sentences. I watched her gestures, her eyes, to find clues about the meaning of her words.

But even the decision not to translate the Japanese into English became a political one. This film was sold to almost every public educational broadcaster across the country with the exception of the Knowledge Network, ironically located in British Columbia. BC is the province where most of the Japanese-Canadian community lived in before WWII. Although I had a verbal phone agreement that they were going to purchase the film, the deal was suddenly stopped when a more senior executive found out that there was untranslated Japanese dialogue and subtitles. At a face to face meeting, I was told that audiences wouldn’t be able to understand the film, but when I offered to translate the film into English, the producer I was dealing with stumbled and stuttered and it became clear there was another agenda at play.

Mike: Because the number of queer Asian indie media makers remains modest, I’m wondering if you find yourself pulled into arguments of personal expression versus community hopes?

Midi: Yes, the number of queer Asian filmmakers/videomakers is still relatively small and yet the numbers have steadily increased over the years. The responsibility that one feels is of course personal and depends very much on the scale and form of the work. For instance the bulk of my work has been “experimental” which gets viewed by very few people. However, when I did my theatrical feature, Skin Deep, starting in 1988 and finishing in 1995, (a seven year nightmare) I was directly faced with a number of community pressures. In this case, it was from the transgendered communities, since one of my main character was a FTM transsexual. Marginalized groups have a political responsibility to demand that characters drawn from their communities are fully developed, three dimensional entities, they have a right and perhaps an obligation to speak out about representation. But in the end, it’s the decision of the artist and what they believe that’s important to the story that ends up on screen. But, within a feature film context, there are so many compromises which are finance-dependent, outside the director’s control. The main reason it took me seven years to make that film was funding, or lack of it. Not that my budget was high by first feature standards, it was just not something that interested distributors. This film was conceived before The Crying Game (1992) and way before Boys Don’t Cry (1999) and as a result, most distributors didn’t see that there was an audience for the film. I remember that I had one meeting with a distributor who really thought that KD Lang should be cast as the transgendered character, for no other reason than she was a known lesbian, not that that made any sense. But, I think that if the deal was truly predicated on hiring KD Lang and I would have received all my money for the film, I might have done it.

Mike: Was your decision to make the dramatic feature Skin Deep (85 minutes 1995) based in part on hopes of reaching wider audiences, or even making a living? Did it feel like a departure or an extension of concerns already raised in previous work?

Midi: After making The Displaced View in 1988, I found that I did want to reach a wider audience, but on my terms. I also wanted to explore a more conventional narrative structure and try my hand at writing scripts. Back in 1987/88, multicultural monies were pouring guiltily from the federal and provincial governments, one of the windfalls from this was an internship for “people from various multicultural communities” made possible by the CBC and a production company called Toronto Talkies Inc. primarily run by Paul DeSilva. I was accepted into this internship and along with a handful of others we were taught how to write a TV half hour. The end result of this internship was a possibility that one’s screenplay would actually be made into a thirty minute one-off for national television. I was lucky and my script Then/Now was produced. The story itself was a rather straightforward father/daughter tale. Father has a flower business and wants his daughter to take over but she plans to become a writer, how to tell dad? Oh yes, and the daughter is gay. Deepa Mehta was originally booked to direct but unfortunately had to drop out and instead Richard Flowers, an Assistant Director I had worked with previously in my career as a camera assistant, took on the role. It was great to observe the process of a commercial production from the perspective of a writer and of course I imagined how I would direct the scenes myself. Everything went fine except when an upper executive at the CBC read the script, realized it contained a lesbian kiss during prime time TV and demanded it be censored. The battle was a hard one and Paul really fought for the kiss but in the end, it was cut, left to rot on the cutting room floor.

From this experience and after writing a second TV drama, called Heartbreak Hoteru for a BC production company back in 1990, I decided I wanted to take what I had learned about mainstream screenwriting and try my hand at a dramatic feature. Looking back on the experience now I can see why it took me so long to produce. Although getting top grants from all the arts councils was not a problem, getting viable commercial support was impossible, I was nobody to them. While I had gained a reputation in the film art/festival scene, I had no commercial directing credits, nor had I even worked with actors! After working seven long years on the feature, there was no way I was looking at a future in that world. Making a living as a commercial director was just not in the cards for me.

Mike: Skin Deep’s Alex Koyama is a film director interested in making a movie about tattooing, skin pictures which provide a nexus of pleasure and pain, control and abandon. Alex says to her lover/assistant (work and play are another duality which are deliberately mixed here), “You let go completely. It’s not you anymore.” This confusion/obliteration of identity is emblematized by Chris Black, a young, pre-op transsexual (a woman presenting herself as a man) and by Penny, a woman playing a man playing a woman. Penny is experience while Chris is innocence, though a quickly overwhelmed and dangerous innocence. What drew you to these themes and why did you choose a dramatic form to realize them?

Midi: (as excerpted from an arts council application, circa 1990) My interest in the area of gender identity began ten years ago when I had the unique opportunity to correspond with a young woman who had cross-lived as a man but who was being medically treated as a lesbian. While cross-living as a man, this particular woman was involved in a “heterosexual” relationship with another woman. However, due to a set of circumstances she was forced into proving her “manhood.” Desperately seeking to preserve her relationship with the young woman, she committed murder and removed the genitalia of the male victim, which she proceeded to “crazy-glue” to her own body. She was found innocent for reasons of insanity and confined to a psychiatric institution.

Over the years her story remained with me and due to my own interest in the lesbian community, I began to question whether this woman had gender dysphoria (was uncomfortable with her socially and culturally assigned gender role) or had difficulties accepting her sexual orientation. As a non-medical observer it is impossible for me to guess. However, from this initial incident my curiosity regarding the relationship between sexual orientation and gender role identity began.

In terms of exploring themes of gender and racial identity, I wanted to use a “dramatic” structure in order to attempt change within the conventional film form. In other words, I wanted to place marginalized characters into a conventional cinematic framework and see if I could subvert an audience’s sense of these characters. Again, you must remember that the conventional mainstream film framework I am talking about was pre-Quentin Tarantino, pre-Crying Game and pre-Boys Don’t Cry. So much of what was happening to mainstream cinema in the early 90s had a direct impact on how marginalized characters were represented. So much of what I wanted to explore in Skin Deep became standard film fare by the time my film was released.

Mike: The myth of the break out feature continues to haunt the filmmaking imaginary, I wonder if you might offer your reflections on those who are looking for their moment on the big screen. Has the glass (lead?) ceiling that keeps men helming lucrative TV gigs and monied features in this country changed greatly in the decade since the release of your film?

Midi: Making Skin Deep and then my weak attempts to try and break into the mainstream film and TV industry as a director showed me a side of the industry that I had only previously experienced during my years as a camera assistant or through war stories from other women. Sadly, the war stories were true. There is no question that a glass ceiling exists and most likely continues to exist for women and especially women of colour. In North American productions, men are still looked at as authority figures and given the benefit of the doubt in terms of the diverse subjects they are allowed to explore. Women are relegated to soft women’s dramas, soaps, emotionally-driven stories. Very rarely do women directors get the opportunity to do action movies. If you’re a woman or a man of colour, for that matter, you are somehow lead down the path to make films that reflect your cultural/ethnic background. One only has to think of Mina Shum, Clement Virgo or Deepa Mehta to get the idea. It’s much more difficult for these filmmakers to break out of what the public expects from them in terms of community representation and subject matter. Being Japanese-Canadian, the public’s expectations on me become focused on wartime stories, stories about the internment, about being a JC woman, etc. I think there is a double glass ceiling for filmmakers of colour, one imposed by the industry and another by public expectation.

Now in 2006 the endless landscape of reality TV shows make it very difficult for all dramatic directors. Canadian TV drama—which used to be the bread and butter for many writers, directors, actors, etc. is almost non-existent. As far as feature filmmaking goes, that’s another story. No matter where you are in the world, making a feature film is hard. You have to be prepared for a lot of meetings, compromises, disappointments, delays and disasters. And in the end, if you survive, it may not be with the film you had intended to make in the first place. In some ways I felt that after making Skin Deep. It was too soul-draining to think of continuing on that path.

Mike: In Alphagirls (2002) you work with a trio of performance artists: Kinga Araya walks the neighborhood with a third leg, Louise Lilifeld repeatedly immerses herself in water, stares, or flogs herself, while Tanya Mars does a more conventional filmic turn, talking about her dog Woofie which leads to a My Dinner With Andre conversation about cloning. This trilogy is collected on an interactive DVD for gallery display or home use. Why is that?

Midi: While developing Alphagirls back in 2000, the DVD format was just hitting the consumer market. There were very few interactive DVDs being produced by the mainstream and nothing that I could find produced by artists. The format and all its possibilities were hardly explored; it was mainly used as a distribution tool for releasing Hollywood movies including director’s commentaries and production stills.

To quote myself from the Alphagirls website: Alphagirls continues my exploration of non-linear narrative structure working within the boundaries of recorded performance. I chose to deal with performance art as the basis of the DVD project in order to shift traditional concepts of live performance and audience interplay. Conventionally, performance art lasts for the length of the performance. Film or video of the performance is considered documentation of the artwork and not the artwork itself. Alphagirls shifts this concept of an appointed time and space performance and forges a kind of cyber-link between audience and performer.

From an aesthetic and stylistic standpoint, I am interested in utilizing the most appropriate and complimentary technical practices that enrich the visual impact/relationship to the viewer. With Alphagirls, I have combined the high-end technology of the DVD format with simple digital toy recording devices such as the Tyco toy camera and the Trendmasters digital camera. The premise of Alphagirls centres on advancing technologies in relationship to a feminist framework. The three performances are as diverse in their subject matter as they are in the execution. Tanya Mars’s piece, My Dinner With Woofie is a seemingly simple commentary on cloning; Kinga Araya’s Grounded (III) focuses on a bodily manifestation of female identity in a public space; and Louise Liliefeldt’s Quarter After, is an intense portrayal of the physical and psychological nature of work/labor. Through this diversity, Alphagirls highlights the possibilities of interactive performance art through the digital frontier of DVD.

Mike: Interactivity was a great watchword of the 90s, promising a liberated viewer finally able to become their own director. But one rarely encounters interactive work these days, what has become of these hopes?

Midi: Yes, buzz words, interactivity. Hmmm. I’m afraid that I am a product of my times. I love technology and my gaming obsession comes into play a bit around my own work. When the DVD format was introduced I was excited by the possibilities and wanted a new way to approach audiences. In fact I even went to the New Media Lab at the Canadian Film Centre and dove into the whole “interactive” thing. What I discovered was that for the most part, the world of film and video are rather separate from web-based, interactive works. Often the people who are the best at coding and the technical side of online work or interactive projects do not have an arts background. There is no motion picture history for many new media producers to fall back on so content can become overshadowed by technology.

In the case of interactive DVDs I think that the reason why there are so few works done in this format is because the technical specifications are so limiting. DVDs must be authored to conform to standards so that they are playable on all computers and DVD players. This can be very frustrating to an artist trying to push the limits of the format. When I got the disk for Alphagirls authored, I went to the best commercial house in the city and to this day my disk was the most complicated job they have had. I could go into a lot of boring technical information, but let’s just say that the format didn’t quite live up to what it promised.

I still believe that artists have not even touched the surface of possibilities for interactive work. It is a new field with constantly shifting parameters and one really has to understand the tools before one can produce meaningful work. On some levels, I don’t think Alphagirls was terribly successful, because in the end, too much was left open to the user. I couldn’t figure out a way to direct the interactivity of the work. But I did learn an enormous amount about the format and interactivity. I think that in some ways the piece worked better in a controlled gallery environment than as an “at home” experience.

Mike: Can you describe how you used interactivity to enhance each of these performers?

Midi: The interactivity for each performance is slightly different. Each of the artists were given a set of parameters to work with such as:

-Each artist had to work with a different low-tech visual format (a toy camera of some kind)

-Each artist was limited to fifteen minutes of visual time

-Each artist could work with up to five different audio tracks

-Each artist could access up to four subtitle/title/pop-up menus

From these parameters I worked with each artist independently and using their previous work as a basis, we co-created performances that would exist in the DVD realm. Tanya Mars’s work was developed from her on-going interest in story-telling. Her performance, which deals with the subject of animal or pet cloning was based on the movie My Dinner with Andre. We decided that her piece would break down the fifteen minute time restriction into two video and audio tracks, each approximately eight minutes in length. On one track Tanya was having a discussion about cloning her dog Woofie with her friend, David. On the other track, David is talking to Woofie about Tanya’s desire to have him cloned. The performance can be viewed as two separate scenes or can be switched between both audio and video possibilities. Ideally, I would want the viewer to watch both tracks as an entire piece and then switch between the two. Further, each track contains two “flashbacks” of sorts. These are scenes that reflect or comment on the primary viewing track.

In Kinga Araya’s piece, Grounded (III), she wanted to play with language and movement in different parts of the city. We used five different tracks each approximately three minutes long. In each of the tracks Kinga navigates her way through different parts of the city with three legs. On the audio tracks she speaks either Polish, Italian, English, French or gibberish. As the viewer manipulates the audio, the story or voice-over continues to progress in these different languages. From a visual standpoint, Kinga’s location is constantly shifting as one manipulates the angle button on the DVD remote control.

In Louise Liliefeldt’s piece, Quarter After, we used four tracks of audio and video, each beginning at staggered times. Her actions on each of the tracks reflect her specific interests in endurance performance art and body/mind relationships. So on one track, she is submerging her head in a tank of water, on another, she is performing a self-flagellation, on the third she is walking on a “bed of nails” and on the last track she is staring, directly confronting the viewer. Like the previous performances the viewer can either experience the performance as separate pieces or intermix each of the video and audio tracks (independently of one another) and discover different connections between the actions.

The entire Alphagirls project works in conjunction with the website www.alphagirls.ca. The user of the DVD is encouraged to go to the website to find out more about each artist, their artist statements, bios, clips of the DVD, etc. Once the user has looked at the site (scrolled over a number of links) there is a key that appears on the upper right corner of the screen. A number becomes visible if you mouse over the “key.” When the user enters this code into the DVD they can then access an “easter egg” or hidden bit of information. This information is only available on Tanya Mars’ performance. When the code is entered, an additional “secret” track of video is available to the user.

Overall, the technical DVD aspects that I was dealing with were so new at the time that some of things I had wanted to do could not be achieved.

Mike: The Basement Girl (12 minutes 2000) is a beautifully crafted brief about a young lonesome in her apartment grieving the fresh wound of a relationship suddenly ended. She turns to TV to find a way to begin again. Why is the text in French and why the oversized subtitles?

Midi: In order to answer your question, I feel that I have to go back a few years before Basement Girl was made in 2000. After I finished my feature, I was exhausted and seriously wondered if I could ever make another film. In the meantime I was hired by MAC Cosmetics to make a video, and what started as one project continues today. I’ve now done over 100 videos for them. This experience pushed me into video and it was thrilling to have the opportunity to make work someone actually paid me for. One of the projects I did was a feature length “basic training” video for all new MAC employees. I co-wrote the script and turned the somewhat dry information into a little story modeled after an Aaron Spelling-type show, with perfect looking characters and their perfect lives, almost a nod to Paul Wong’s video Prime Cuts (1981). This video had to be translated into six languages and I supervised all of them.

With the MAC videos under my belt and various languages buzzing around in my head, I decided to make Basement Girl into a “foreign film.” I had dealt with the Japanese language in The Displaced View, and a bit in Skin Deep, but here I wanted to use French, as a good Canadian, and give another level of meaning to the film. In the French voice-over, the Basement Girl’s ex is actually a guy, not a woman as in the English version. Echoing some of the male references in the English version, it was my little subtle (subversive) statement on bisexuality.

The French language (for those audiences who don’t understand French) further transforms the way the video is viewed—from the perspective of a foreign film. When an audience goes to a foreign movie there are different expectations at play and different readings that can be made. By dealing with TV imagery in a “foreign” context a shift is made in the audience’s relationship to familiar or popular North American culture.

As far as the subtitles, that was a bit of a technical thing. Although we shot most of the film in 16mm we also used my fave toy camera—a modified Nintendo Gameboy camera, which ended up as a video element. I transferred all the film to video, cut the piece, did the titles and then transferred it all back to film. The mistake I made was not testing the size of the video titles in terms of the eventual film transfer.

Mike: The voice-over recites, “For now it is only the space she inhabits which is real.” She is “outside the picture” and also “outside life,” merely an observer. She watches TV not in order to lose herself but to learn how to desire again. Clips of TV girl-girl love are recast in luminously recoloured sitcom fragments. Why the extensive reworking of this familiar footage, and how did you collect these moments?

Midi: I had planned to use pop culture feminist icons in the film such as the Bionic Woman, That Girl and Mary Tyler Moore, so I just kept popping tapes into my VCR and recording every show I could get my hands on. From that material I selected the scenes or reworked moments to give it lesbian content.

There is no question that for women of my generation, 70s TV shows like the ones I’ve mentioned impacted the way we saw ourselves. We were no longer stay-at-home moms waiting with cookies and milk; we were now career women living on our own, with problems and relationships. I can’t begin to describe how powerful I found Mary Tyler Moore as a role model when I was young. I wanted to pay homage to them and also insert the reality of the Basement Girl into the whole picture.

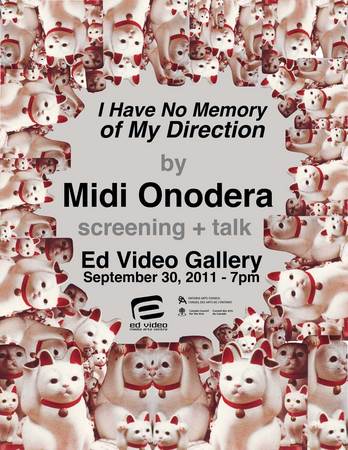

Mike: I Have No Memory of My Direction (77 minutes 2006) is a Japanese travelogue impelled by your voice-over and first person shooting. In the opening shot you say in voice-over: “When she recalled that moment their faces would reappear to her, suspended in the oxide coated Mylar tape like a strange, three dimensional puzzle, the pieces would continuously rearrange themselves, depending on the clarity of her vision. But they never seemed to tell the entire story, the one she knew was there, hidden in the magnetic recording.” Here you suggest that our video prosthesis has replaced memory, or become memory. “Her” seeing relies on the clarity of her vision, but all she is seeing belongs to the videotape. Do you feel that you are creating memory with your work?

Midi: I am trying to remember by making work. In I Have No Memory… I am using a dream landscape as the foundation of memory, which like dreams can be elusive, illogically, emotional, confusing, etc. In reference to the opening scene with the young girls by the shore, this scene stands in for a “frozen moment” in time. But the voice-over describes this memory/moment as unstable: it’s ever-changing, mutating into other bits of time, other stories. The “real” story of the girls is not visible to the naked eye or the camera. No matter how hard the narrator tries to recall that moment, there will always be something missing.

Since the meaning of “memory” is the ability to store, retain, and subsequently recall information, as an image-maker I am constantly and unconsciously remembering things in a kind of linear narrative or filmic timeline of sorts. Sometimes the whole sequence is readily available, sometimes only a small detail or close-up is trapped on the edge of forgetting.

Mike: And how is this related to the film’s larger project: to see through your father’s eyes?