Notes (April 2013)

Sadly, anything other than watching the films themselves brings back only memories of compromise, pretension and frippery; mostly on my part. It was important for me to have gone through that. Some people are born honest, others have to learn it the hard way. I don’t see anything, in the current landscape, like the kind of work that attracted me to the Funnel. We seem to have become very distracted viewers. When the framed event can be stuck inside a website or played on a handheld device, it’s a very different world from the space of a theatre with its presentation and audience. Until recently I worked as a sound editor/recordist/designer for film, television, radio, theatre and gallery installations. Presently, I work as a shipper in a bakery and have no intention of returning to work in the media industry.

Opening night at the Funnel: honestly, I don’t remember all that much. I probably put in less than a day on the construction of the space itself and although I was a founding member, I was quite tangential to the organizing of the events at that point. Still, I did show my process film “1 to 51” as part of the program. 1-51 was a piece that I made while working at a film laboratory. I was a timer/printer. One day some footage arrived that had shots of the American Bicentennial celebrations. There was one of a cloud of red, white and blue balloons being released in downtown Cincinnati. I made a copy of it, then would attach that copy to the tail of the next item that I had to print. When the next day’s round of printing came in I would splice yesterday’s copy of that shot onto the tail of the material to be printed and retrieve that section from the new print after it was processed. I did this once every working day for about two months. Like making a photocopy of a photocopy, the image went from recognizable to increasingly abstract as it lost detail and the colours became more generalized: less tied to their original objects.

At that point, the film had no fixed sound track, so I press-ganged my friends and borrowed some sound equipment from a commercial film that I was working on to perform “music” for that screening. The piece took its starting point from the drone compositions of Lamont Young: I held down a key on a Mini-Moog and played back a four track tape of prerecorded tones to make a large continuous chord. I remember that someone played sax against this harmonic wash and I suspect there may have been a guitarist. It was all rather loose but it wasn’t like an improvised free jazz piece. Notes were brought in slowly in various harmonies working to create “beat” patterns. Part of me saw this as avant-garde but it really was just a tarted up, historical re-enactment of things that had been done over a decade ago in New York.

About the evening itself I really do not recall feelings or the excitement surrounding the event, but this probably has more to do with my inability to draw narrative from the situations around me. Spectators recall far more of a given event than participants. Locker room interviews tend to be tersely worded by comparison with the post-game analysis. For some reason, I didn’t stay very long after the screening. My memories of the night come mostly from a meeting that was held the next week to discuss how the evening went and to tighten up how screenings would be presented. Apparently one member had invited a Ryerson school buddy who loudly and drunkenly voiced his abuse for “film artists” at the after screening party. I remember that story because the member in question said something in his own defence that has remained with me over the years, “It’s my right to have friends who are assholes.” As perfect a defence of freedom of association as I’ve ever heard.

The open screenings were to me the most consistently interesting thing about The Funnel. I rarely saw anything that profoundly affected me but it was the liveliest aspect of the whole operation. People who never screened their work in front of an audience got that chance. It would be hard to describe to someone for whom there’s always been a YouTube. Access to filmmaking equipment was hard enough: curiously the means to present a film to an audience was even harder. Before the Funnel there had been ad hoc film nights, at UofT/Hart House, at artists’ studios, but nothing all that regular. The Funnel provided that space and time. Somebody always showed up with something. There were always film students from York, Ryerson or Seneca showing their film projects, that was a given. And the private auteurs, guys that made epics in super 8 that always acted like they were the only real filmmakers in the room. One night a quiet, middle aged man came to an open screening. He brought with him close to an hour of super 8 footage of stuff that he had shot from his Spadina Avenue apartment balcony. Had he ever even heard of Andy Warhol or Michael Snow? I doubt it. There were many filmmakers like John Porter and Villem Teder who would quite regularly show something that they were working on. They used the open screenings as a kind of test bed for their ideas. The first time I ever saw any film work by the Fast Würms it was at open screenings. They would do little quick knock-off films that were truly funny. I would occasionally show work there. Short experiments, found footage re-edits. We had this old 16mm print of a cowboy B-picture, “Villa”, about the Mexican outlaw Pancho Villa, that I would perform randomized, cut-up pieces on. One night, I had nothing to show so I did a performance piece, still under the Cage-Fluxus influence. It was called, “This Is The Film That I Am Showing.” I grabbed a reel of film from the projection booth, walked up in front of the screen and said to the audience,”This is the film that I am showing.” I held up the reel, turned it around in my hands to show it on both sides and then sat down.

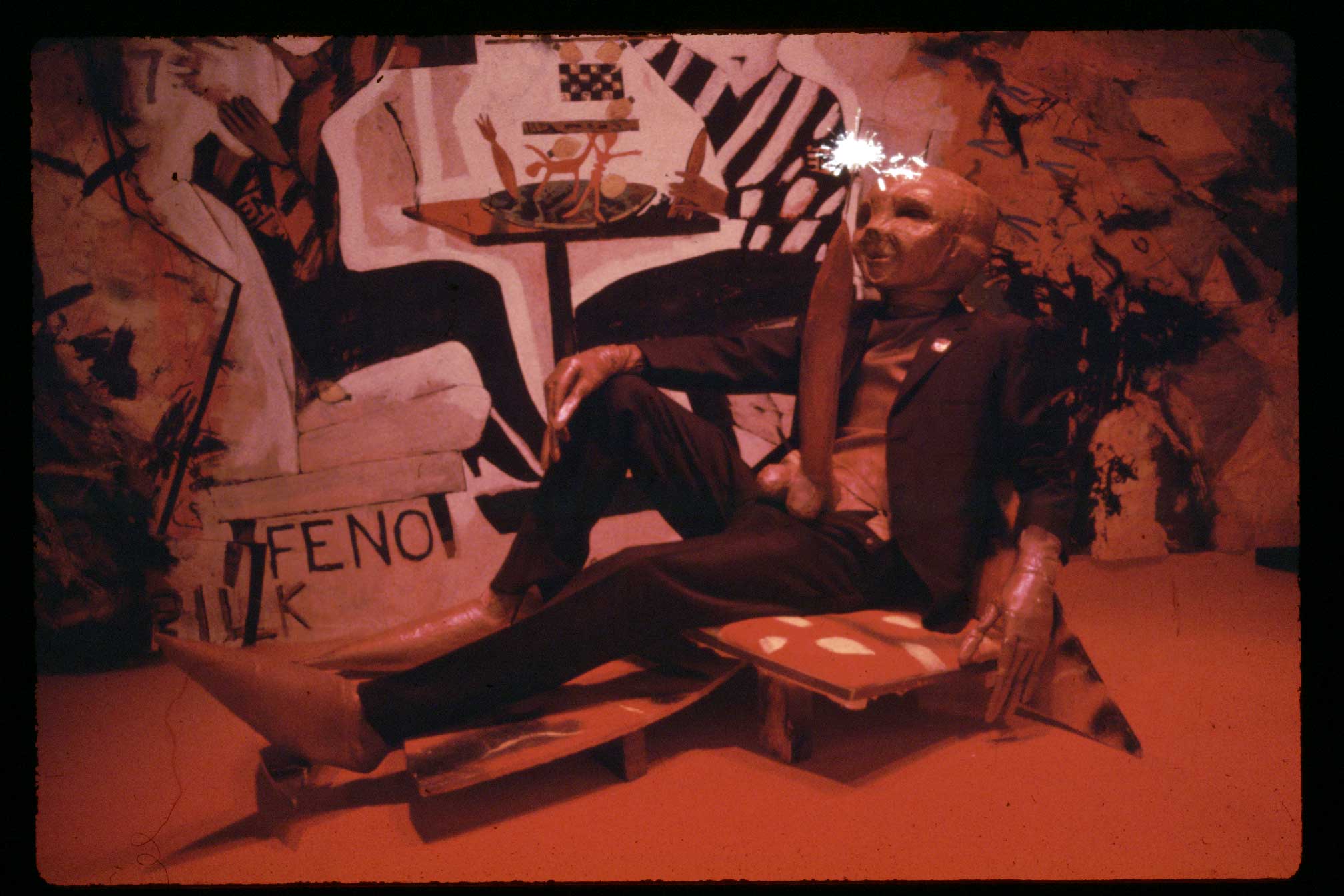

Be My Magnet by Fastwurms

I have no interest in dispelling or disputing any claims about what The Funnel or Funnel was in relation to the Toronto art scene or the local film industry. We were one of many competing interests in the culture industry of Toronto. For the most part there was a backlog of experimental film that had been produced and was being produced around the world and there was no regular venue for presenting it. The people involved were largely filmmakers so getting involved in production and distribution was a predictable consequence. These activities consume enough of one’s time that any grander theory would have to come for somewhere else.

For myself, I can only recall that the entire experience of “watching a movie” can be as demanding an act for the active spectator as looking at a painting, attending a live performance or reading a novel or poem. A tired analogy, I know, but its consequences are acute. These spaces and times are growing distant from common experience. For many these opportunities do not exist for reasons of culture or lack of privilege. But even among those that could, there seem to be be fewer who would. Briefly, in rare moments, I did feel as if, beyond the “discourse,” the art-talk, there were works that pointed to a greater continuity, a richer reading of what we are. Works that in the dark did not just present shadows but the outlines of human brilliance. Brief moments strung together between the opening and closing of a shutter projecting light on a screen. That way of looking is still available but increasingly difficult to experience. When film is gone, how will we know what video looks like? At the heart of it is the event, going somewhere to see something, and that there be other people going to the same thing. Our screenings of artists work with the artist present were curiously part science demonstration and part philosophical presentation. Was one watching a sacrament and a sermon or an experiment before the Royal Society? When they build a shopping mall they stick a Cineplex in it. Cinema has found its place in our economy. I remember a time when we really didn’t know what to do with it, so we made it do all kinds of stuff. We watched what each other did and some of us chose to think about it and bring those thoughts into the next thing that we made. Toronto had a lot of catching up to do. I lived at a time when that was important and there was a value attached to that.