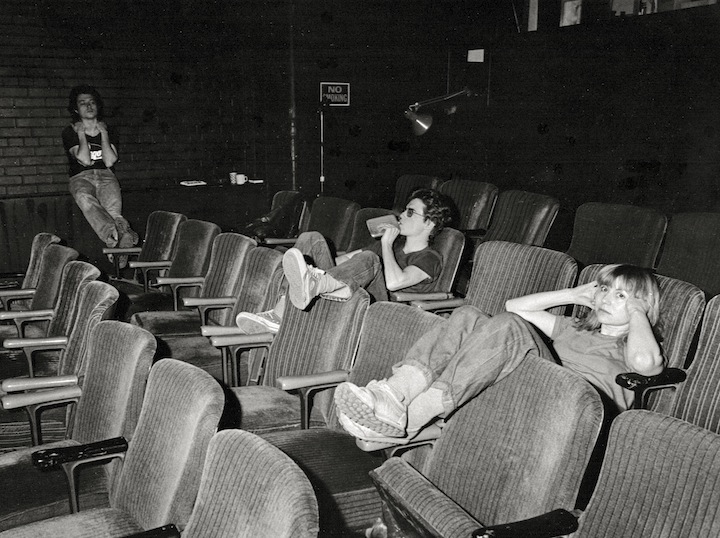

3 Voyeurgeurs: Edie Steiner, John Porter, Annette Mangaard, posing for a poster shoot for an upcoming group show at The Funnel

Post Punk: an interview with Edie Steiner (May 13, 2013)

Edie: I was in the media studies program at Ryerson in the early 1970s, my main discipline was fine art photography (social documentary studies and portraits). I made films because it was required but I didn’t like the formal structures we had to work within at school so I dropped it. After school I worked in the music industry during the punk and new wave era documenting musicians.

Mike: Did you ever visit the punk club run by the Diodes called Crash ‘n’ Burn?

Edie: I went every weekend in the summer of 1977 and saw all the bands. It was a fairly large basement space, there were chairs but most of us would stand or wander around. It had an underground feeling. I don’t remember a bouncer, in those days events were pretty accessible. It wasn’t the only club, there was also a space called David’s on St. Nicholas Street. A Space brought Talking Heads into the Ontario College of Art and Design. Some people did larger shows, Patti Smith played Massey Hall when I met her, she came to my studio.

I was working in a collective doing design for emerging musicians. Some of my pictures were made for a predecessor to Now Magazine, Toronto’s free weekly, called Night Out. Around the same time I also did a shoot with Blondie’s Debbie Harry for the art magazine Impulse. There was more of a connection between music and art at that moment. The urban cultural underground was smaller and more connected and Crash ‘n’ Burn was part of that. I had moved away from art galleries and started publishing in music journals.

Mike: The punk club was in the basement of a four story warehouse building at 15 Duncan owned by CEAC (Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication). The basement is where The Funnel began, and there were events upstairs on the fourth floor nearly every day of the week. Did you ever attend CEAC events?

Edie: Only once or twice. My focus was more on music and photography and documenting the emerging music scene. Eventually it became larger and more commercial and I grew less interested in it. For me the music community was no longer breaking ground and I wasn’t interested in making a living that way. I had tried but it was very difficult. I decided I couldn’t make my living as an artist, I just wanted to have an art practice, and find other ways to pay my studio rent which was quite challenging. Eventually I downsized and gave up my studio and took a room in a house with other filmmakers, like Robin Russell, and a couple of people from Queen’s University who had studied film. It was still in the east end so I could easily make it to Funnel screenings. I missed having a studio and eventually found one at Bathurst and Queen. Good friends from The Funnel like Sharon Cook lived close by. It seemed we were always in the same neighbourhoods with each other so that our cultural practices and social life were intertwined. Geography and personal relations came together.

The Funnel had a theatre and an art gallery run by a small collective of twenty or thirty people. I started going all the time and became a member. I already knew some of the people there and came to know others. When I saw the films they were presenting I thought: this is something I can do. I started to get interested in super 8 as the next step after photographing the punk scene. My practice was about composing images, and I realized that I could that in moving pictures as well as stills. John was always very encouraging. He might have given me a roll of super 8 film for my birthday and I probably presented it at an open screening.When I was still living in my photography studio at King and Parliament, John Porter lived across the street, along with film artists Jim Anderson and Paul McGowan. They were living in studios as well. We were a block away from The Funnel, and one day John invited me to come and see one of his films in a show there. John was a friend I’d met at Ryerson when we were both students. He had a great sense of humour, and was always doing quirky things like leaving a tape recorder running in his locker playing the sound of a forest. In the Photo Arts Building there was a stairway leading up to the third floor, and I remember once coming upon John in costume hanging over the ledge. I wasn’t so interested in experimental film then, and we didn’t start sharing creative practices until I got involved with The Funnel.

Mike: What were the open screenings like?

Edie: There was always an audience. The size would vary, but there would be a core group of twenty, some of the membership was very committed and came out to everything. It wasn’t difficult to get people out, and attendance grew over the years I was involved. Members and non-members would bring work to present. It was a way to do outreach to teachers, film schools, and different communities. I showed my work there for the first time, it was great to be part of a new artistic community.

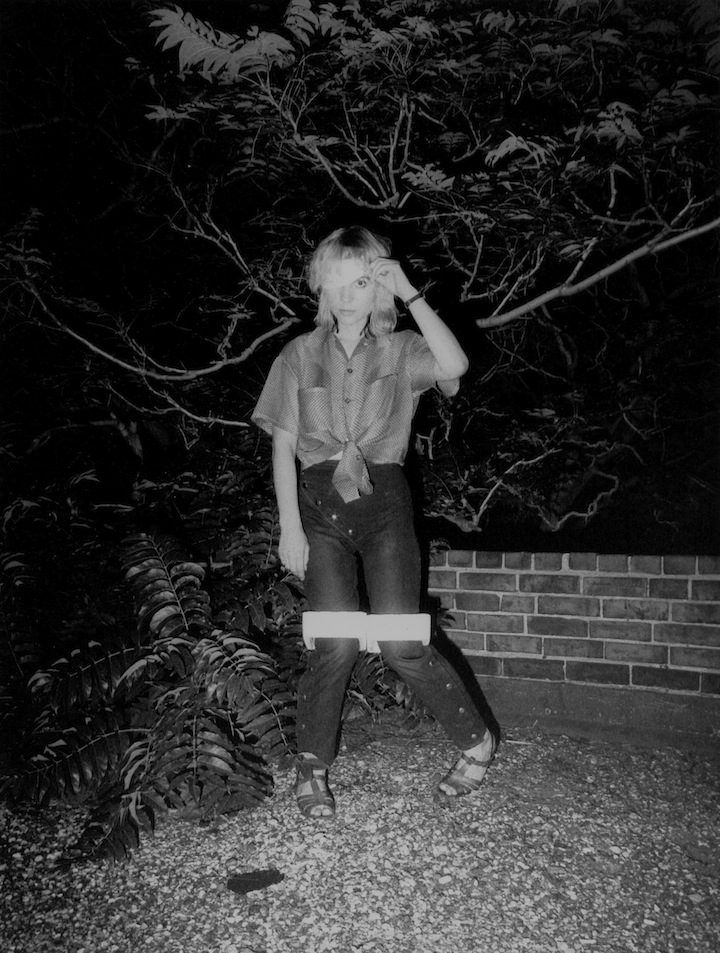

Bruce LaBruce and Edie Steiner (on the roof of the warehouse building where Jim Anderson, John Porter, Paul McGowan lived)

Mike: Did you feel there was a common aesthetic at The Funnel?

Edie: The work members made was unique to each artist. Anna Gronau’s films were formal, Villem Teder’s films were abstract, John’s work featured timelapse. Many of us worked primarily in super 8 and it was all experimental rather than narrative, though some people made experimental narratives.

Mike: Experimental film was a catchphrase of the time. What does “experimental” mean?

Edie: Several things. Artists experimented with the nature of the image and the way the image is produced (the camera, the materials used, the film stock). It might mean pushing boundaries that had already been established in the genre of experimental film. What else could be done?

Mike: Did you see work that impressed you?

Edie: There were a lot of visiting artists, that was one of the most amazing things. People came from everywhere. One of my favourites was Jack Smith, whose week-long performance engaged us as participants in an evolving spectacle that no one, including Jack, seemed to know the outcome or purpose of. We spent days fashioning ornate “bum brassieres” — bras to be worn on our backsides, and Jack was never happy with our work. That week Jack came to my studio for a private portrait sitting. He arrived bearing a large red vinyl suitcase filled with costume jewelry, and later I took him to the St. Lawrence antique market, which he described as “the jewel pit of my dreams.”

The programs were quite eclectic. There was a lot of performance because the space facilitated that, and several group-themed events as well. We had inherited a lot of found footage from various labs and people would reconstruct it, sometimes according to a theme. One evening was called Showdown at Sundown, and used reworked pictures from a single western film. Martin Heath and Marc Glassman did a performance with a flaming sombrero onstage. I performed a version of I Walk the Line by Johnny Cash, with a film loop running back and forth. Derek Graham performed with me (a video artist from Guelph). I played guitar and sang, with Derek on guitar and another woman, Gloria Toth, on keyboards. The film loop had only two shots, one showed a group of cowboys galloping over a hill, and the second a couple moving in for a kiss. It was run backwards so the couple was continually retreating from their embrace, while the horses ran backwards.

I remember seeing Ross McLaren while he was filming his punk documentary at the Crash ‘n’ Burn, though I didn’t really meet him until three or four years later. We got to know each other at The Funnel and became very good friends. We created music together, and started a band called The Elementals. On nights the theatre was dark, we made experimental recordings onto reel to reel tape using the sound booth. I would play keyboards and guitar and sing while Ross played guitar. We played together for a year, I think he still has all the recordings. Paul McGowan got involved a little bit and then it fell apart for me because I thought there were too many people trying to do too many things. I dropped music for a while until I met Chip Yarwood a couple of years later in 1984 and started recording with him in his studio. Chip was more committed to music, whereas music at The Funnel was more abstract and anything goes.

I did a number of performances at The Funnel involving looping film projections with live music but not with The Elementals. In 1982 I had a solo show in the gallery and a screening to launch it. In the gallery I showed photographs of music personalities at the time, including the all-woman band Fifth Column and other local artists. I was transitioning from portraits to urban objects. The gallery was a great space because it was a gathering point for conversations at intermission or after the show. It was a very social environment, and we sold beer. Often we would move from The Funnel to a party at the warehouse where John Porter, Jim Anderson and Paul McGowan lived. Dot Tuer eventually lived there too. There was a lot of social life at that time.

For my solo show I did three or four film performances that I wrote the music for and performed live. Ross McLaren worked the soundboard. Caroline Azar from Fifth Column had a miniature keyboard, almost a toy, that she played, and I had a Moog synthesizer courtesy of Peter Chapman, a Funnel member and filmmaker, along with my electric guitar. A lot of the songs were repetitive, chant-like pieces. The films weren’t formally conceived ahead of time, they were improvised. With super 8 you could be very free form. The music was somewhat improvised as well, though the lyrics would be written out so I knew what I was going to sing. There was one called Examination Aboard a UFO (4 minutes 1983), I wouldn’t call it narrative but it was performative. I shot it in my studio, I set up the camera and performed a character constantly reacting to light sources. It was as if I was under examination. Later on I was wounded, and wrapped a large bloodied bandage around my head because my brain had been examined by aliens. There’s a funny story related to that. In 1986, Annette Mangaard and I took a collection of Funnel films down to New York’s Collective for Living Cinema. It could be a big hassle bringing films over the border officially so our story was that we were just going to visit friends and had brought personal work with us. The custom agent picked up my film and said, “What’s this?” I said, “That’s just me and my friends on vacation.” He read the title out loud, “Examination Aboard A UFO?” I worried we had been caught in that moment but I said, “Oh we were just having fun,” and he let us go.

My last super 8 film was made in 1987 and I showed it at an open screening. It’s called Who Is Number One? (11 minutes, 1987) a satire on the 60s television show The Prisoner. The show ran just seventeen episodes from 1967 to 1968. The soundtrack was one that I co-composed with Fred Spek that is now available on CD for screenings. Fred was also a fan of the show so we decided to do the soundtrack together. We sampled some of the dialogue from the film, particularly the lines “Who is Number One?” and “Where am I?” The film recreates and reprises the characteristics of the cult TV show. Stephen Castledine was an English friend who looked very much like the lead character Patrick McGoohan. On the show he’s a former spy who is being kept on a remote island and interrogated about why he quit the secret service. In this science fiction detective story, everyone has numbers instead of names, and Number One is the guy in charge. Who is Number One?

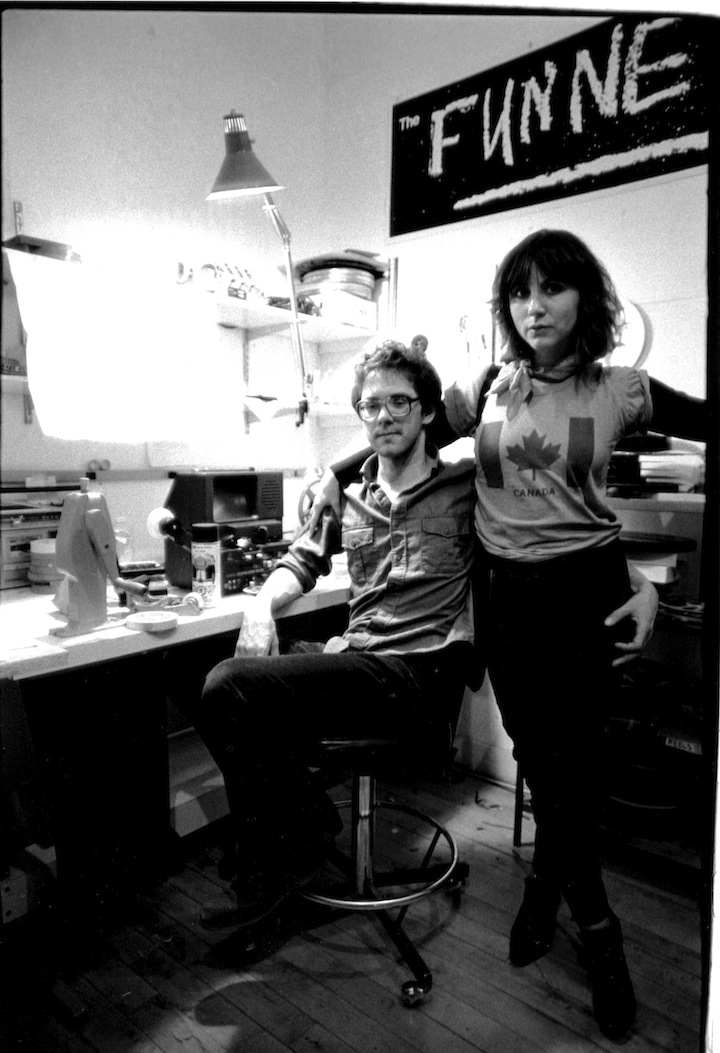

John Porter, Villem Teder, Edie Steiner, Stephen Niblock outside the Mercury Theatre after a Funnel group screening, Toronto, 1983

Mike: Did that film feel out of place at The Funnel because it was narrative?

Edie: No, the story was pretty abstract. But at that point I decided I wanted to work in 16mm and was starting to write scripts. I was still connected to The Funnel but I decided to become involved with a different community and make a narrative film. I joined LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) in 1985. I wanted to move into narrative filmmaking, and that wasn’t part of the mandate of The Funnel. I didn’t want to just make experimental work, I’ve always been interested in literature and telling stories. It always took me a long time to launch a project, and years later that film became Places to Stay (20 minutes 1991) which dealt with my German heritage.

Mike: What was the difference between LIFT and The Funnel?

Edie: LIFT was a much larger group, and people were more interested in making bigger projects that would have a more mainstream audience, either via broadcast or festivals. Artists worked with bigger budgets, so instead of a single filmmaker doing everything on their own you might have a crew. LIFT offered scriptwriting and technical workshops. There was nothing wrong with The Funnel, I just wanted to move on. I reinvent my practice every few years, sometimes because I feel I’ve reached my limit, or because I haven’t succeeded in achieving what I wanted.

Mike: In 1986 John Porter became The Funnel’s director.

Edie: I was still involved, though John and I might have had a difference of opinion about narrative versus non-narrative. Some felt that LIFT was taking Funnel people away. A few of us were members of both.

Mike: Did you know anything about John’s firing?

Edie: I know that when he was hired, John gave up a personal filmmaking grant because he felt that it was a conflict of interest to take a salary from an artist-run centre and hold a grant at the same time. I don’t know anything about his firing. I know that John often had differences of opinion around censorship and the Censor Board but I wouldn’t be the person to ask about that.

Mike: Do you know anything about the move from King Street to Soho Street?

Edie: I think promised funding didn’t come through for the new space and that’s what caused the demise of The Funnel. Some thought the new space wasn’t affordable. By the time they moved, I was no longer a member. I visited the new space but it felt very different, it didn’t have the same sense of energy or community, and a lot of people I knew had moved on. I was already part of another community and had met a lot of new people. I was less interested in what happened at The Funnel and it seemed that only a short time passed before The Funnel no longer existed.

Mike: Did its closing come as a surprise?

Edie: Not really because other arts centres had come and gone. I’d heard the news that the financials didn’t fit the new space. I’d lost a studio myself during the eighties, I knew how difficult it could be to make the rent.

Mike: I think part of the idea behind the move was that if the theatre was in a more central location more people would come, but it turned out that less people were interested. Does that seem unusual?

Edie: At the same time as our communities were growing they were becoming more fragmented. In the mid-seventies there were very few music venues or art galleries, but eventually new ones started up, and people gravitated from one space to another. The city of Toronto had completely changed by the late eighties, as the culture expanded people got older and became more entrepreneurial. A lot of us were very young in the early eighties, and after a decade of struggling as artists many people dropped the ball. I was always disappointed when that happened. Stephen Niblock is someone I admired so much as a filmmaker and a visual artist, I was shocked when he felt he had to give up his art practice when he had a child. I was saddened that people couldn’t afford to make work or weren’t getting grants. As people got into their thirties, communities dispersed and reshaped, people went on to do other things. New people created spaces that were different physically and ideologically than what we thought was important in the eighties.