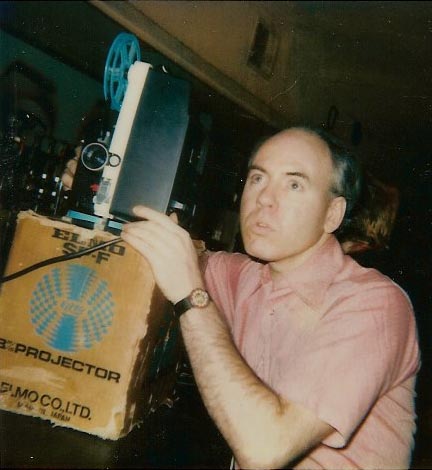

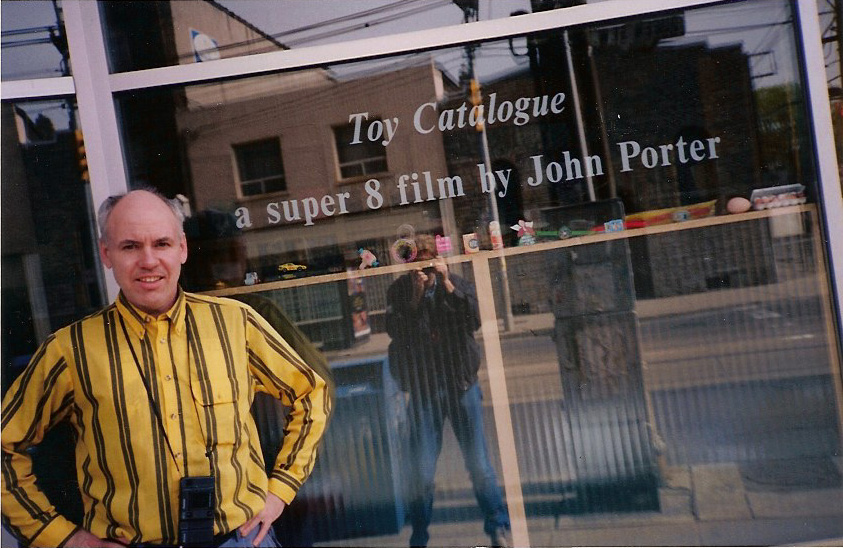

Mr. Super 8: an interview with John Porter

John: I grew up in two different worlds. The first was on St. Clements Avenue, near Eglinton and Avenue Road. It was urban, downtown, fun. There were a lot of kids around, and because we were less than a block from school, I could play baseball there in the evenings. Or use the sidewalk on the hill for our soapbox derby cars which we made out of wood and baby buggy wheels. My family moved out to the suburbs just before the end of grade eight in elementary school and it was quite traumatic; as a result I failed the first year of high school. Then the Board of Education instituted the first Junior High Schools, so in order to repeat grade nine, I had to change schools again. The suburbs were snobby, you couldn’t get together and play ball, kids were at home watching TV, myself included.

In my Junior High a lot of tougher kids were bussed in and they livened up the school. I took inspiration from them and got into trouble there. I acted up in class and was sent to the principal’s office. That’s not a surprise, I’m still a trouble maker today. That’s what I’m known as around the arts community here.

I had two older sisters, one died of cancer in 1999. Both were teachers. They had a rough life too, both of them burned out at least once in their career and had to quit temporarily. It had an effect on them emotionally and physically, and I decided I didn’t want to teach.

Mike: Were they surprised that you became a filmmaker?

John: They were born in the early 40s, and I was born in 1948. It felt like we were in different generations. They liked Elvis, I liked the Beatles. We didn’t get to know each other that well. None of my family fully understood what I was doing. My mother was an artist but always thought I was just a photographer. I was on my own in that sense. My father was very smart, he worked as a chemical engineer and a physicist, but it was still difficult for him to understand the point of experimental super 8 filmmaking.

I didn’t do well in high school, interestingly enough history was my worst subject, though I love it now. After high school I acquired a love of local history which they never taught. I only finished grade 12, and then worked for a couple of years as a junior cost accountant at Moore Business Forms out in Weston. I was also a shoe salesman. I’d been doing still photography and acting in high school, then after I finished school I shot my first super 8 film. That’s when I decided I wanted to go to Ryerson Polytechnical Institute in downtown Toronto and study photography and film.

For my first film in 1968 I rented a camera from Janet Good. As soon as I started shooting I realized this is what I want to do. I don’t think I wrote a script, it was so short and simple. The story was inspired by a National Film Board short called Toys (8 minutes 1966), an anti-war film that showed plastic soldiers coming to life. I wanted to make an anti-war-toy film too. I had a friend dressed in a soldier’s uniform running around a vacant lot being chased by kids with guns. They killed him in the end. It’s called Sandbox (3.5 minutes 1968). I find a lot of people’s first films have running in them. It’s the most simple action.

I didn’t know anything about movies as art except for Spaghetti Westerns. We were fifteen and the guys I hung out with would all go. It amazed me that movies could be so stylized, like dance, with the unusual music and long, slow movements. They helped to inspire me to make movies. My first movie had a spaghetti western look to it.

I was disappointed to learn about professional filmmaking at Ryerson and what a pain in the neck it was. They only taught 16mm, no super 8. Being there for five years helped form my whole philosophy about super 8. I’d think, “Well, I’m going to show those people and make nothing but super 8 films and really good ones.” 16mm was so expensive, it was like being up in the suburbs again. It required so much equipment, and a crew and labs. 16mm seemed like a middle class form. I remember getting into an argument with Stan Brakhage who said, “Filmmaking is an expensive practice.” Well, that’s narrow minded, you’re not considering the option of making super 8 films and showing your original so you don’t have the cost of the print, and working without sound. You can make a film for as little as a painting, $50 or less if you want to. Even Stan Brakhage thought all filmmaking was expensive, no exceptions.

The first couple of years at Ryerson we were making shorts, I still like to show some of mine when I can. I was doing time lapse and time exposures, keeping the camera shutter open for extended periods. After Norman McLaren died they released test footage he had made for some of his dance films, and it turned out that we were doing similar experiments at the same time. Thanatopsis by Ed Emschwiller (5:12 minutes 1962) was very inspiring for me, it showed dancers dressed in white against a black background with blurred motions because of his use of time exposures. That’s what I was experimenting with at Ryerson. But once I got into the final year of the three year course I got into trouble again, just like in junior high and high school. In two different years they failed me and tried to kick me out. I appealed and convinced them to take me back for one more year, so I wound up being there five years, from 1969-74. I liked the battles and arguments around super 8, and being around young people my age making films, that was an education all by itself.

I went to a lot of repertory cinemas, I considered that part of my education. I would read the newspaper listings and figure out which movies I wanted to see, sometimes two or three a day. My father gave me an appointment book where I wrote down the screenings I was interested in, and I circled the ones I actually attended. I continue to do that today, only now I mostly go to programs of experimental shorts in bars and underground cinemas. But back then there were only occasional public screenings of experimental films at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Since 2005 I’ve documented the alternative film scene in Toronto and beyond on the home page of my website, listing every alternative film screening I can find, day after day. My home page and Past Events pages are an extension of these appointment books.

After Ryerson I felt there weren’t enough alternative screenings in the city, so I bought a 16mm projector and began running my own 16mm screening series at the Don Vale Community Centre in Cabbagetown. That was before it became the Toronto Dance Theatre. I borrowed free films from the public library and the National Film Board and put together auteur screenings – programs of shorts made by a single director.

I had been experimenting with time exposures at Ryerson in 16mm, but I knew I wanted to go back to super 8. I had heard about a Braun Nizo super 8 camera that did time exposures. I answered a classified ad by a young teenager, Ron Mann, selling his camera out in the suburbs. I took a long bus ride out to his house and negotiated with him and his mother in their kitchen. It cost $400 and I still have the receipt. I had just started working as a letter carrier and I was flush with money. (laughs) I bought this Nizo and started shooting time lapse films.

Mike: Timelapse means shooting one frame at a time over an extended period, and when the footage is projected, hours of shooting are condensed into just a few minutes, so everything appears sped up. You called these Porter’s Condensed Rituals.

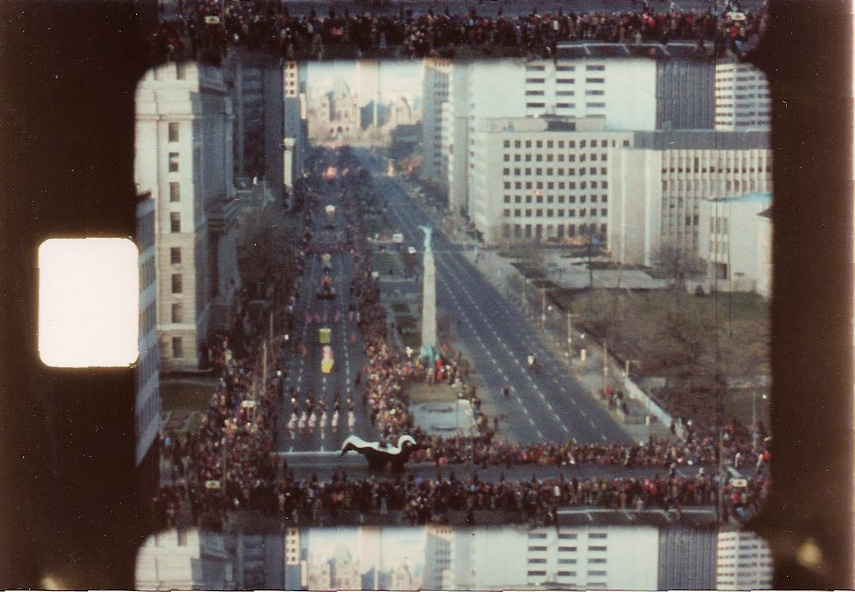

John: A reference to Campbell’s Condensed Soup. I designed a mock soup can of “Porter’s Condensed Rituals” and photographed it for my film titles and a poster. The first really successful Condensed Ritual was Santa Claus Parade (4.5 minutes, silent, 1976). It was shot on two rolls, and edited down to six minutes in December 1976. I had worked the year before as a machine operator at Zurich Insurance Company on University at Richmond where the parade passes every year. It’s since been torn down, but it was where University bends east a little bit, so the tower had a view right up the center of the street and it was eight stories tall. I got permission from my past employers to spend Sunday afternoon up on the roof. I had a lot of fun up there shooting the parade.

After that I started looking through local newspaper listings, just like I did with Repertory Cinemas, trying to find events that would be good for timelapse filming. I shot A Day At Home (3.5 minutes, silent, 1976) in my co-op apartment, setting the camera in the corner of the common room with people coming and going. Fashion shows seemed like a good subject. I shot major shows in Fashion Show 1 (5.5 minutes 1978), Fashion Show 2 (3.5 minutes 1978) and Fashion Show 3 (7 minutes 1981). An event called Fashion Burn caught my eye, it was happening at the Crash ‘n’ Burn club, in the basement of the CEAC (Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication) building on Duncan Street.

Mike: Did you just show up and walk in with your camera and tripod?

John: Yes. Part of the fun of shooting some big public events was going through the red tape to get permission. But at the Crash ‘N Burn there was no red tape. At CEAC? This was 1977, there were little security concerns back then. It was a relatively innocent period. This was before portable video cameras were widely engaged, and the only use for a super 8 film was as a home movie.

As a letter carrier, I didn’t have my own route – that paid more money and you didn’t get bored doing the same route every day. I was interested in local history, so I liked seeing different neighborhoods. I was delivering on Seaton Street when I ran into Frieder Hochheim, a former Ryerson film classmate. I told him I was shooting these super 8 films, and he told me about the open screenings at The Funnel. I had never heard of The Funnel, but it turned out they were in the basement of CEAC where Crash ‘N Burn had been that summer. I already had quite a few films by that point, so I showed up at the Open Screenings in the fall of 1977. CEAC had already been showing films upstairs for a year, and held their first super 8 open screening in October 1976. It was basically Ross McLaren and his Kodak super 8 projector and a few friends like Adam Swica and Anna Gronau helping out. In 1977-78, The Funnel opened up in the basement, continuing the open screenings both for super 8 and 16mm, and hosting some visiting filmmakers. The Funnel people liked my films so I liked going there.

The space was very small, though the ceilings were high enough to have risers, and they had a little projection booth. There were good sightlines. There were maybe 30 seats on the risers, but there was space for chairs off to the side. The room was rectangular, split length wise by support beams, so not many people could sit on the other side of the beams and see the whole screen. There might have been room for 40 people maximum. On the other side of the beams there was a photocopy machine that Ross used a lot, maybe a table and a coffee machine. Apparently Ross lived there for a while, sleeping on the floor.

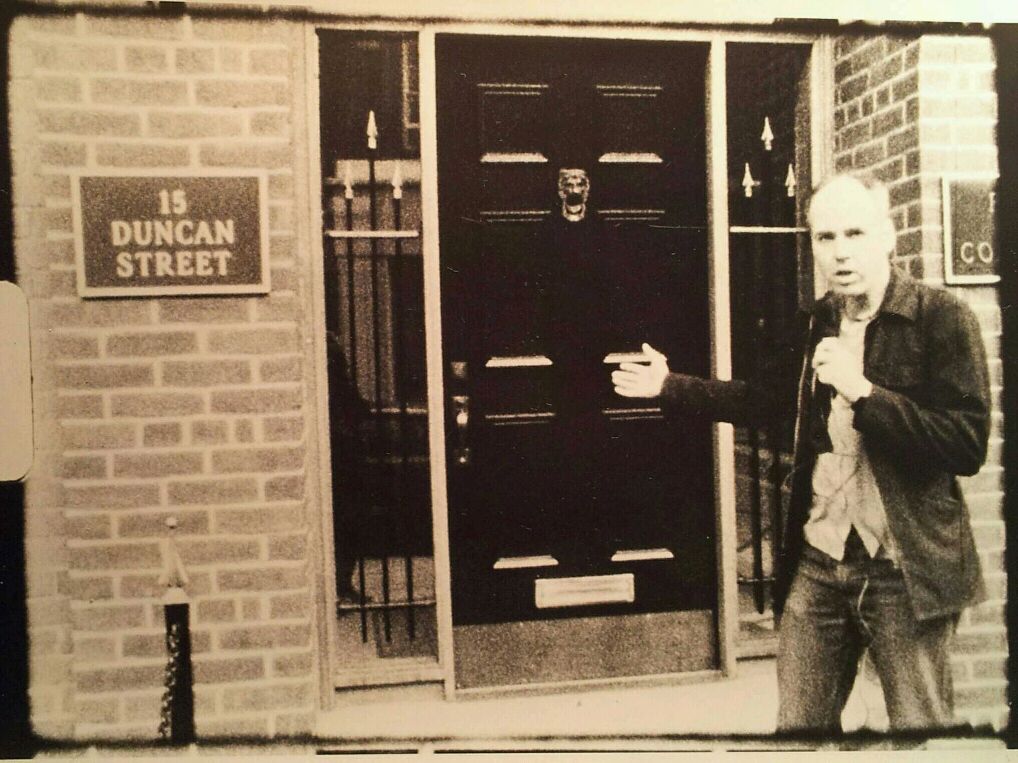

7 Year Itch at The Funnel by John Porter

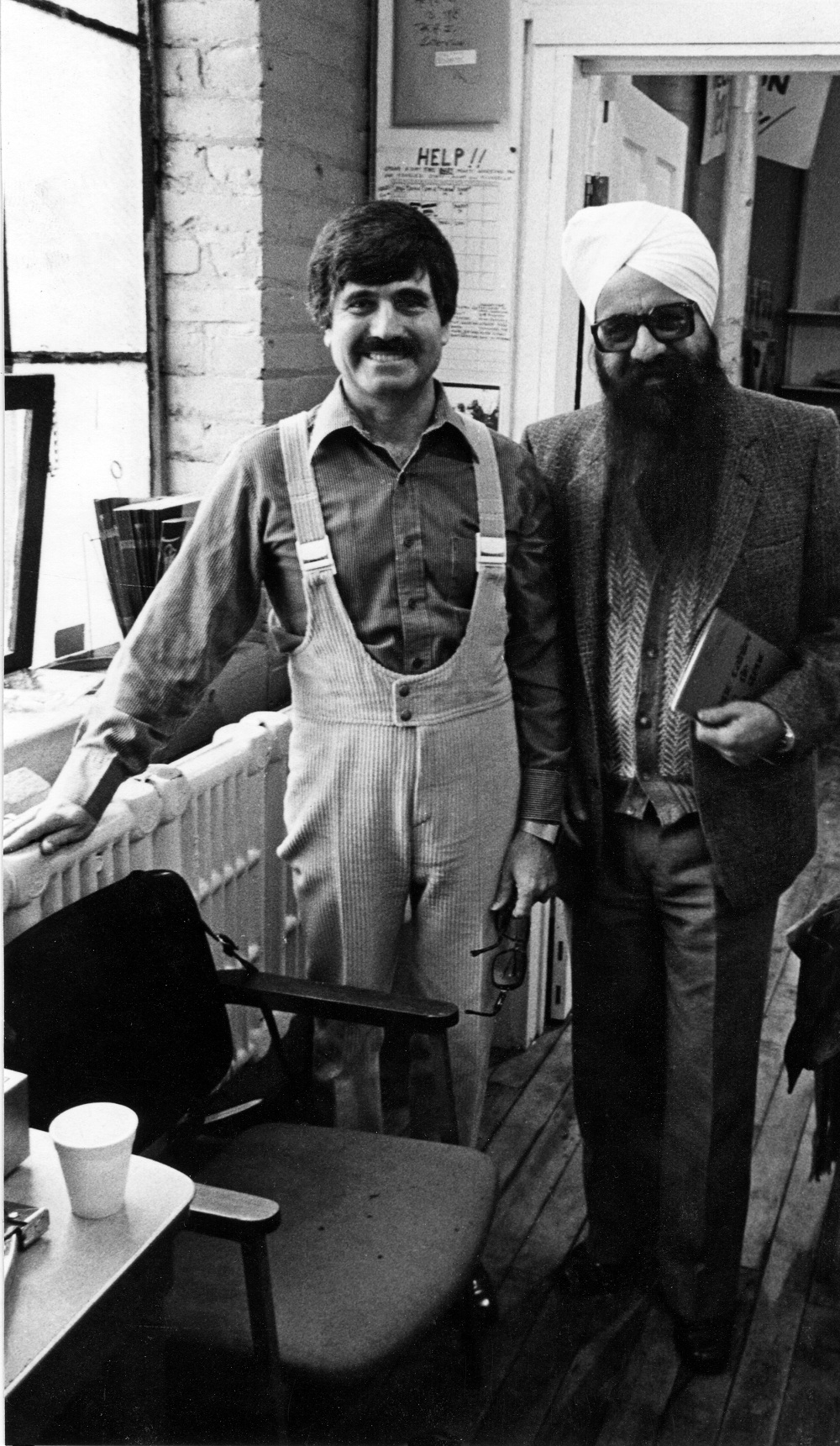

John stands in front of the door at 15 Duncan Street, former home of CEAC and The Funnel.

Ross and I went back in 1985. At the beginning of every season of The Funnel we did a launch program where all the members made a super 8 film on a theme. Because this year was the seventh anniversary at the new space, the theme of the program was Seven Year Itch. But I asked: what about the first year? I wanted to point out that there was an earlier year at the old space that they weren’t commemorating. So Ross and I went back to the Duncan Street building and got into the basement which is now an office and shot a super 8 sound film of what the Crash ‘n’ Burn and The Funnel space looks like today. We didn’t have permission so we had to negotiate. I had dropped by a week or two before in my brash way and spoken to the receptionist. When I came back to shoot with Ross we were greeted by the owner of the finance company, “Oh yes I heard you were here last week and were pretty confident…” I had already rubbed him the wrong way. I had to explain to him what I was doing, and started talking about the history of the CEAC. “Oh those anarchists!” he said, he knew all about the arts organization that had been in the building, and Strike Magazine, and their sympathies with the Red Brigades terrorists. That was a big mark against Ross and I too, but still we managed to get in. I followed Ross with my sound camera as he said, “This is where we had the booth and the screen, and there was a photocopier over here.”

The Toronto Super 8 Film Festival (1976-1983) grew out of informal, super 8 parties held in the homes of Ontario College of Art students. They were making super 8 films and meeting one another. Ross was one of them.

I showed a film at the Super 8 Festival in 1977 and it was selected for a big screening at the Cinema Lumiere at the end of the festival. There were 300 people and listening to them react to my film was amazing. The other screenings were at the Ontario College of Art. But the festival was only once a year, and it wasn’t very experimental. Ross was involved with them and he also had a problem with the absence of experimental work, that was one of the reasons The Funnel started. There was no place for experimental super 8 film anywhere. The AGO would only show 16mm experimental films. I went to the CFMDC and there were all these 16mm films and I thought this place isn’t for me. It was just like Ryerson. The Funnel was the only place where my work fit in, it was a sort of home. The Super 8 Festival was mostly about making professional looking movies in super 8. Sync sound was introduced to super 8 in 1975 and that was a big impetus. With sync sound people could make features! Dramas! The Richard Leacock approach was to use sound super 8 like an early version of portable video and make socially relevant documentaries. It was exciting for some people to make movies about the content. They had a trade show featuring the latest equipment, and all the screenings created a fun circus atmosphere. Lenny Lipton came a couple of years in a row and showed his 3D super 8 films, but he was just shooting home movies. That was indicative of the festival.

CEAC helped to found the short-lived Canadian Super 8 Distribution Centre in 1976, which in turn published a Directory in 1977 with 118 super 8 films, some 8mm films, and some videos, by 48 Canadian artists. It was inspired by the success of the Super 8 Festival, there were so many films being shown, the feeling was that they should be distributed.

Mike: Did they distribute your films?

John: I’m in the catalogue but they didn’t last long enough to do any distribution. It was more of a dream at that point, going through all the films shown at the Festival, then contacting artists and asking if they wanted distribution. There was a falling out between some of the people at the distribution centre and CEAC and Ross, so they lost their Ontario Arts Council funding and were kicked out. I think it only lasted a year.

The super 8 open screening at CEAC in December 1976 was called After The War, a title that refers to the super 8 distribution people trying to walk off with the money. CEAC received funding for the Distribution Centre, I’m just guessing what happened, and then a couple of people incorporated the Distribution Centre without telling Ross. They took the money and decided it’s their centre. CEAC said no, we applied for and received this funding. When property becomes involved, whether it’s money or equipment or jobs, that’s when trouble starts in these artist run centres. Greed sets in.

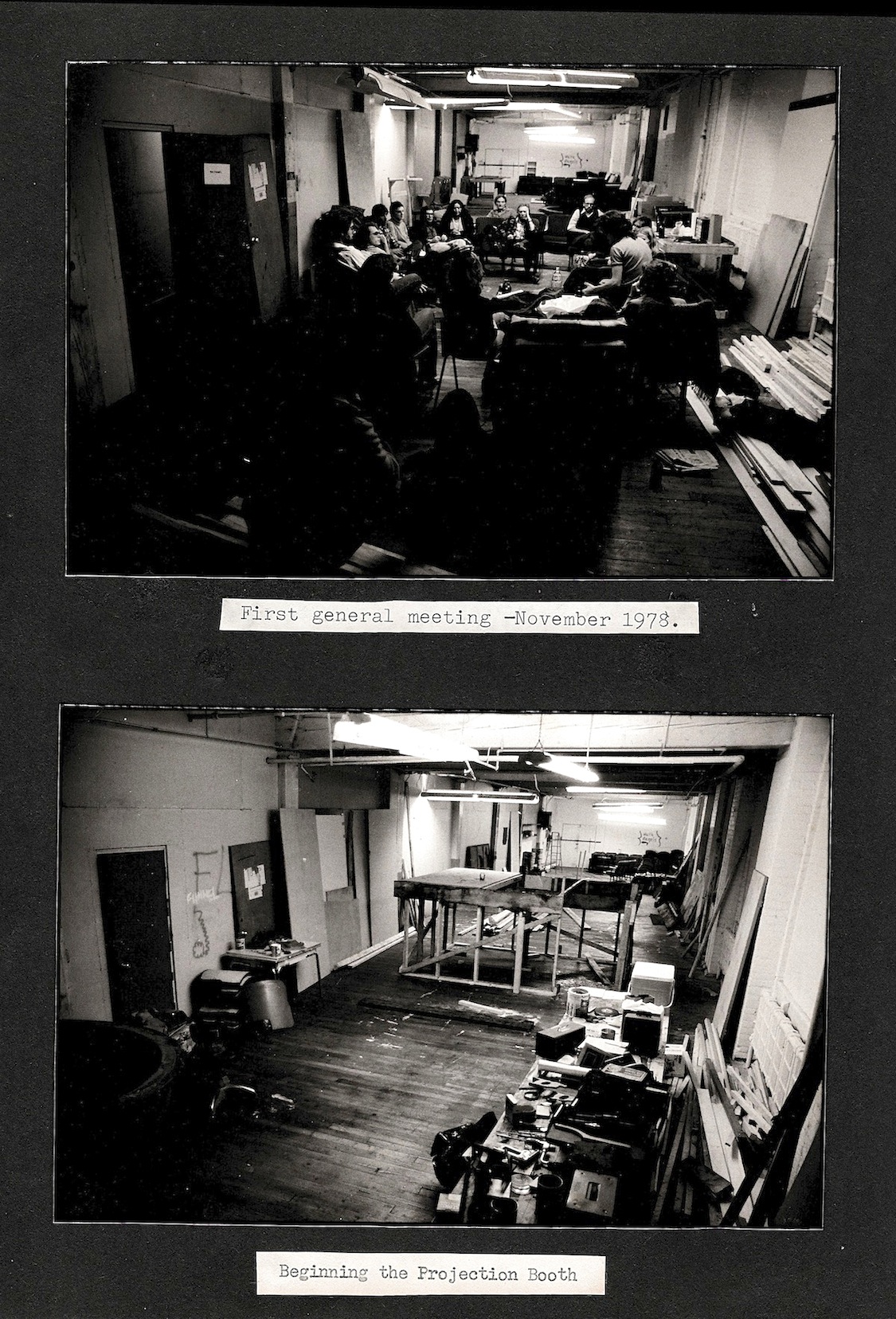

I don’t miss any experimental film screenings now. But back then, I only went to the open screenings and a few of the visiting filmmaker screenings. I didn’t know anything about CEAC or Strike and then the problem hit in the spring of 1978. That’s when their publication Strike had a cover story about the Red Brigade terrorists in Italy, and the article seemed to suggest that CEAC favoured the Red Brigades. This story hit the front page of the Toronto Sun, the headline read something like, “Taxpayers money funding terrorists.” They lost their funding as a result, and The Funnel had to decide what to do. So a meeting was called at the Funnel space, in the basement of CEAC, in the spring of 1978. It was the first time I had seen there were so many people, as many as thirty, who were regular supporters. There were a few people there I knew, like Bruce Elder from Ryerson and Jim Murphy from the CFMDC. The issue was to decide what to do. CEAC wanted The Funnel to write a letter of support to maintain their funding, as a kind of character reference. Some felt this would implicate The Funnel in the terrorism charges. I felt what’s the harm in writing a letter that doesn’t say we support their politics, but acknowledges that they’ve been very good to us, they’ve given us this space and brought in experimental filmmakers. But the overwhelming consensus was that we wouldn’t write this letter, we’d move out and find a new space. We needed money up front to sign a lease so we all agreed to become official members and fork out a hundred dollars each. They spent all summer looking for a space and incorporating. Ross and Anna seemed very business-like and efficient, they would have known what to do. It had been called The Funnel since September 1977. The lease was signed in November 1978. We built the theatre pretty quickly, in one month. We opened in December 1978.

Mike: Did you help build the space?

John: Yes, I loved that, getting to know all these people.

Mike: Was there someone in charge?

John: They were very organized. David Bennell was the building foreman who would assign tasks. There would be a handful of people on specific days, ten at most, when it would take on a party atmosphere. You could drop by anytime and there would be someone there. It was an empty warehouse space on the east side of the city. We built the projection booth and risers, and put in nearly a hundred donated theatre seats. There was a lot of assembly line work done on those seats because they needed to be repaired. There was lot of cleaning, painting, plastering.

Mike: I came around a couple of years later, and it seemed to me that David mostly didn’t make films. I always wondered how he could be so dedicated when didn’t identify as a filmmaker.

John: Do you remember Tom Urquhart? He never made any… I think he made a super 8 movie about his wife, but he was there a lot too. They were supporters of experimental film. They just liked the scene, which included local celebrities like Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland. Together we built this underground theatre from scratch and had filmmakers visit from around the world. It was so exciting.

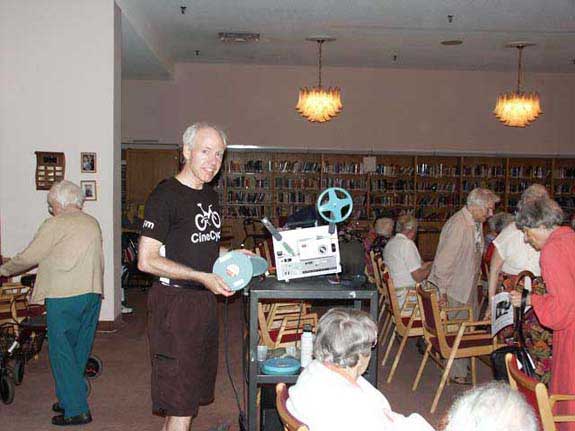

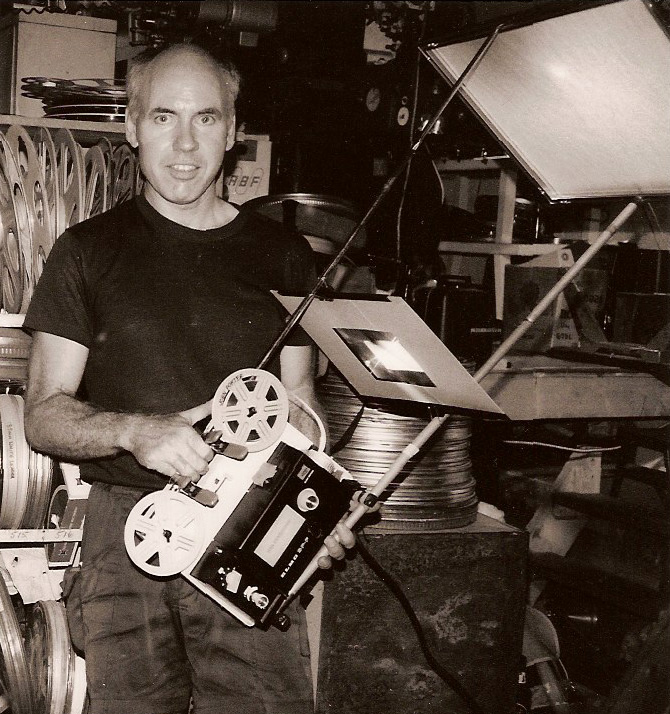

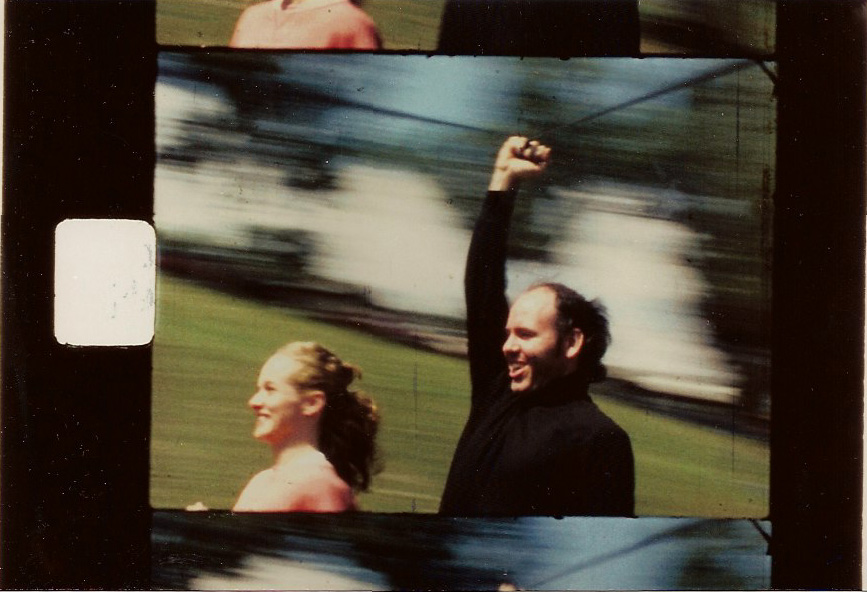

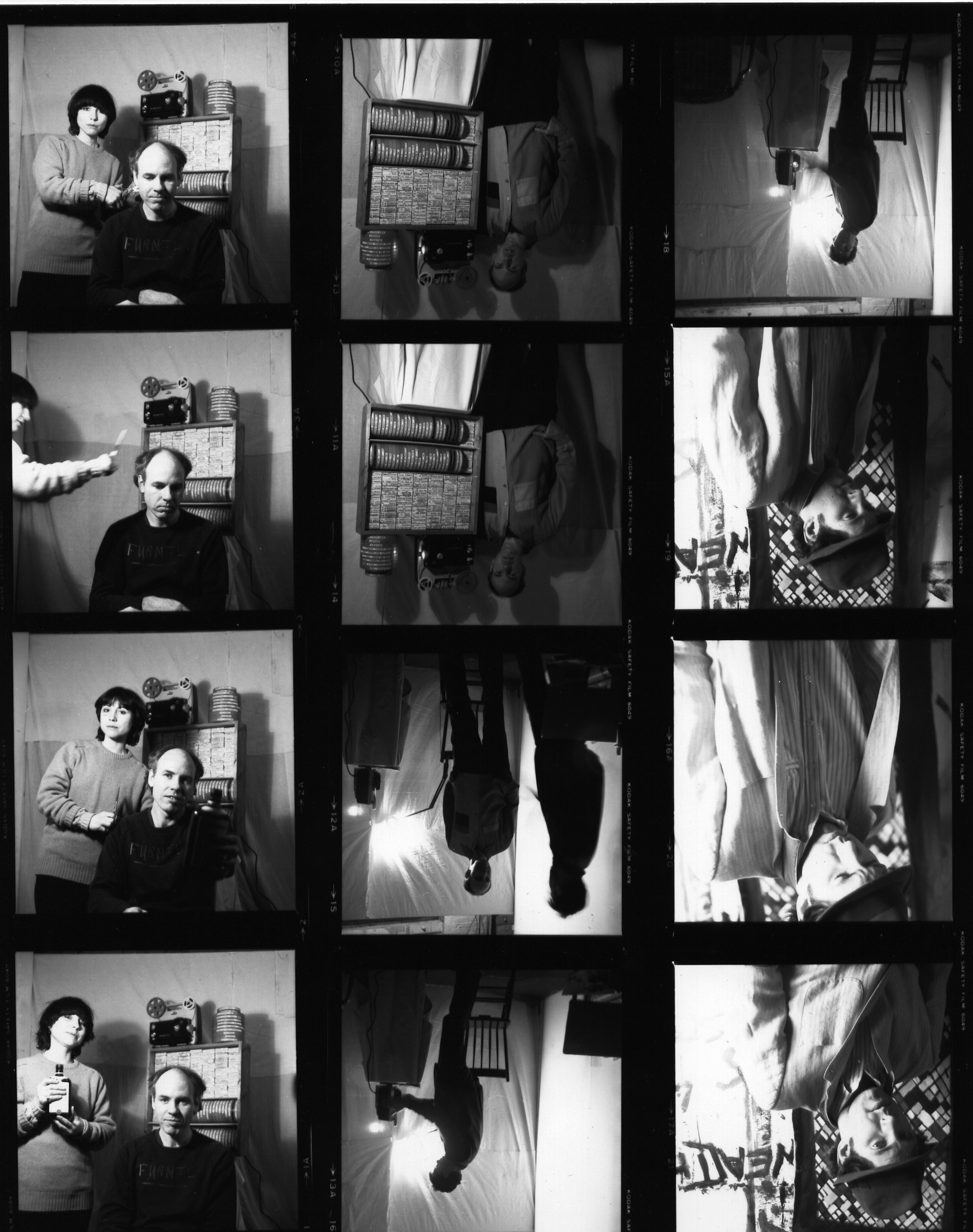

Edie Steiner, John Porter, John’s 200 films, Stephen Niblock (on the right), all photos by Edie Steiner

Mike: Did the open screenings continue?

John: Oh yeah, they were always the backbone of The Funnel. One of the things that led to the end of The Funnel was that the Censor Board banned them. They were illegal, and once the Censor Board found The Funnel, they said you can’t have open screenings because we have to see the films in advance. When the open screenings ended it took a lot of spirit out of The Funnel community. Later, I collected testimonials from people like Martha Davis and Fastwurms who said that the open screenings were what brought them to The Funnel. I think it was around 1981 that the Board caught wind of what was going on, probably through an article in the newspaper.

Mike: Did you feel it was a bad decision to stop them?

John: I can go both ways. I like litigation, and the decision was made to take the Board of Censors to court. The Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society was formed, a group that included Anna Gronau and David Poole. In order not to jeopardize the case, The Funnel would obey the law. But we kept listing the open screenings on the posters, that was our policy, every month it would say, “Open Screening cancelled by the Board of Censors unless there has been a change in their policy since this poster went to press.” Just to remind people of the issue. But after the court case, open screenings remained illegal. The Funnel didn’t resume them, and they removed that statement from the poster. It was a retreat that I disagreed with.

In 1986 I became the director, then the programmer of The Funnel, and got into trouble with The Funnel board for organizing an open screening which may or may not have been illegal. Instead of submitting the actual films, we could submit a form for each film, and the Censor Board would rate the movie based on the programmer’s written description. “Examination by Documentation.” It was a lot of paper work, and sometimes there were time constraints because the film would arrive with the filmmaker that afternoon, so you’d talk to the artist on the phone and get a verbal description. The description is a bit arbitrary, you could withhold details, but it also puts the signer of the form in liability, they could be charged if there were any problems.

I submitted a form, and under the heading “Title” I wrote, “Open Screening,” and for a description I wrote, “Various subjects, various content included in various films brought by filmmakers to open screenings.” It was the truth, but vague. It was a game, I was testing the Board of Censors to see whether they actually read the forms or only rubber stamped them, because often we would have a dozen or more forms per screening for programs of shorts. My open screening was approved. There was no mention of any obscene material, but they gave it an Adult Audiences Only rating, because if they couldn’t see the film, it was automatically restricted.

I held this open screening without The Funnel board’s specific permission. I decided I was the programmer and this is what I wanted to do. In the next board meeting I was told, “John, you should have told us, we could get into trouble. If the Board of Censors found out that this was an open screening…” I said, “But they’ve signed the form.” They responded, “But they probably didn’t read it, and if they catch us, we could be charged.” I think the Censor Board would have just warned us. So I was fired partly on that account, because they said they couldn’t trust me. My strong position against the Board of Censors was well known, and they were afraid that I was going to do something else. OK, you can’t have open screenings, but what else does he have up his sleeve that is going to get us into trouble? This was in late 1986.

Mike: Do you remember a general member’s meeting perhaps a year later where you spoke about opening up the membership?

John: It was actually around the same time, probably a bit earlier. That was a significant meeting. Dot Tuer and I championed this cause. Dot and Jim Anderson and I were living in a big warehouse just down the street from The Funnel. We had a big dining room with big windows and had great discussions there about art and politics.

We had this idea that The Funnel should be more democratic. In order to become one of the 30 Core Members you had to be voted in by the board. And the purpose of that was to keep it experimental, this policy was a direct result of what had happened at the Toronto Filmmaker’s Co-op where conventional filmmakers working in large format films needed more equipment for longer periods of time. It dominates what goes on in the organization. We wanted to know who the membership applicants were. Would they be taking our 16mm camera out for a day, a week or a month, that sort of thing. But after 10 years I felt that people knew what The Funnel was about, and mainstream people weren’t interested, we weren’t getting a lot of people asking to be core members.

Our idea was to give Associate Members a vote on who could be on the board, among the Core Membership of 30. This was our idea about how to open up the organization: let everyone vote for who would be on the board. Dot was very passionate when she presented her arguments, but it didn’t pass. The way it was voted down was sort of suspect. We needed a 2/3 majority to pass the motion, and it was defeated by only one vote. Villem Teder had given his proxy to the chair David Bennell, who used Villem’s proxy to vote against it. But when I spoke to Villem afterwards, he said he would have voted for the new member policy.

That was another blow to The Funnel. The open screening ban was hard. And as soon as we were associated with the court case against the Board of Censors we were visited by safety inspectors who demanded $35,000 in renovations. It took six months of hard work. One thing after another knocked a bit of the spirit out of the Funnel community. Some Associate Members told me it was also my firing. They thought I was the face of the Funnel because I was there at all the screenings, talking to people, whereas other Funnel people would hang out in the office at the back. So when they fired me, these members lost a connection to The Funnel. Voting against giving Associate Members a vote turned a lot of people off. After that I think their active membership went down, it was harder for them to get volunteers, there wasn’t as much of an all-for-one and one-for-all feeling at the screenings. Shortly after that, in early 1987, they decided to make a big move to Soho Street because they wanted a more central location. They certainly found one, right in the middle of Queen Street West, but the move required a lot of physical volunteer work, and increased funding, and they had to do this with the membership depleted, and the spirit gone. They were in a weak position. If they had laid low and stayed put, I think they could have survived.

Mike: Did you help build the new theatre?

John: No, after they fired me I went to screenings, but I didn’t want to be involved there. It took them forever to build the theatre, six months or something, because they had so little help. I went by when it was being built to pick up posters, but anytime I went, there was no work being done. There was a pool table or a ping pong table, and just a couple of people who couldn’t work because they were waiting for someone else. I heard from volunteers that they were told that work would be done at a certain time but then no one was there to let them in. It was indicative of the low spirits, they couldn’t build a theatre in a month like we did the first time.

The Funnel held screenings for less than a year on Soho Street, then lost funding which meant that they had to give up their lease. They had to tear down the whole facility that they’d just built which would have broken their hearts. I don’t think they would have had any gumption left to go on.

Mike: How did you become such an anti-censorship advocate?

John: Well, first of all I didn’t like the end of the open screenings. That was my favourite thing, The Funnel wasn’t the same when they ended. And then my nephew was turned away at a screening I did in Peterborough, at the Canadian Images Festival. The Festival had their own troubles with the Censor Board before my screening.

“The Canadian Images Film Festival has been charged with violating the Ontario Theatres Act for screening Al Razutis’ film “A Message from our Sponsor,” a short film which the Ontario Censor Board had refused to pass without the deletion of several seconds of explicit sexual material. Charged by the Ontario Provincial Police were: Sue Ditta, the director of Canadian Images; Al Razutis, the director of the film; Ian McLachlan, who is a member of the Board for both Canadian Images and Artspace, where the film was screened; and David Bierk, the executive director of Artspace. Under the Theatres Act, the four face fines of up to $2,000 and jail terms of up to one year each. Had the Ontario Provincial Police, whose Project Pornography squad conducted the investigation which led to the charges, chosen to lay criminal rather than civil charges, the four could have faced fines up to $25,000. At press time, the trial date had not been set.” Cinema Canada, May 1981

After they were convicted, the Canadian Images Festival had to obey the law, which meant that my films, which I would not submit to the Board of Censors, were classified as restricted. My sister Nancy lived in Peterborough and brought her nine year old son, and they were turned away because he was underage. For my films, which are perfect for children! That was a very emotional moment for me. Ever since then I’ve hated the Board of Censors. I disagree with people who won’t publicly stand up to it, which is most of the arts community and most of the film community in Toronto. They just want to keep it quiet, they don’t even want to talk about. And other filmmakers continue to experience incidents similar to mine in Peterborough.

Mike: What do you feel should be happening now?

John: Whatever happened to 6 Days of Resistance (the city wide anti-censorship festival held in 1985)? What about a month of resistance, a lifetime of resistance? In a way it has continued, because people are still showing unapproved film and video illegally. But during 6 Days of Resistance they were doing so knowingly and defiantly, in resistance. Now they’re doing it out of ignorance, believing the law doesn’t apply to them anymore. When the Glad Day book store went to court there was no support for them at all from the arts community. They refused to submit a videotape they were distributing for prior approval because it was such a low volume sale item they would lose money if they had to pay the classification fee. They fought for years with no financial or verbal support from the arts community, and in the end they won, but as usual they also lost. Because the government rewrote the law, just like they did the last time they lost, including more media, expanding their powers. I guess the community feels: “What’s the point? Even if you win, you lose.” Almost everyone has just given up. But for me that’s not an excuse to keep quiet. They don’t understand that most screenings are illegal and that people could still be charged.

Mike: Why are screenings illegal?

John: Because the work hasn’t been submitted for prior approval and classified by the Ontario Film Review Board. Most festival screenings are like that. You have to apply to the Board to put on a festival and obtain an official waiver that makes all the screenings restricted. You have to post signs saying it’s restricted and people at the door are required to ensure that no minors enter. Most exhibitors don’t even know they have to submit, so they allow minors to attend illegally. But the law is not about content, it’s about targeting film and video regardless of its content. It’s a shameful situation that we’re being discriminated against, compared to other art media. We’re treated as if we’re convicted child abusers on parole, we have to get permission from the parole board before we show our work to minors. They don’t trust us. Most everyone seems content with that.

Mike: You’ve done film performances around censorship.

John: Well, that started during 6 Days of Resistance, and then I toured it around. They were based on reading the film classification law carefully and literally. I stand up in front of the theatre and demonstrate different things that you could be charged for that you wouldn’t guess. Like holding a photograph in your hand and moving it. That’s a moving image. And what if you run a movie, and put your hand in front of the projector lens the entire screening, so the audience can’t see it, does that have to be approved? I demonstrated that too. I did an installation for Eye Revue Gallery at Union Station, the big train station in Toronto. The sign read Uncensored Movies, and there was a peephole where people could see strips of film moving in the wind of a fan blowing on them.

Mike: Could you talk about your Scanning series?

John: Well that’s a switch, no politics there. Even back in my teenage days as a still photographer I was doing filmic type things – tableaus, panoramas, constructions and photo series. Standing on a single spot, I took several photos while turning around, and when I got the prints back I taped them edge to edge so they made a circular panorama, and carried it out to the same spot and held it around my head. That was an early, scanning type action.

Anne B. Walters came up from Chicago to show her films at The Funnel, and a super 8 installation in the gallery where she hung a projector from the ceiling by a rope. The film showed a 360 degree panorama, and she projected the film as it was shot, with the projector turning on the rope. My scanning is basically the same, only I’ve removed the rope and I’m holding the projector in my hand. That way I can move the projector more easily in different directions.

Scanning 1 (3.5 minutes, silent, live performance, 1981) was not a panorama, but a scanning of the front of the Funnel building that was like a TV scan, where you go across the top, and then back the other way a bit further down, the camera followed a zigzag pattern in order to catch the whole façade of the building, and then I projected it that way.

Mike: The movements of the projector rhyme the movements of the camera.

John: Yes, it’s like a dance with the film leading the projector. I move the projector as the subject moves. Scanning 2 (3.5 minutes, live performance 1982) returned to the Funnel facade, but this time with sound. That was harder to perform because sound projectors are heavier to hold. Scanning 3 (3.5 minutes, silent, live performance, 1982) was shot in front of the Collective for Living Cinema in New York City with their workshop co-ordinator Mary Fillipo posing. I had a screening there the next day when I performed the film after getting it processed in New York in a day. At the end of it, I hold the projector right up against the screen aimed sideways so the image is spread across the screen with only the centre in focus. It was the first Scanning in which I have to pull focus while moving the projector. Scanning 4 (3.5 minutes, silent, live performance 1982) was made in front of the Morissey Tavern on Yonge Street, just north of Bloor, which has since disappeared. Michaelle McLean and John Frizzell used to drink there. I had a drink with them, then had them stand in front while I did these fast swish pans, like Michael Snow’s Back and Forth (50 minutes 1969). It was an experiment to see how much you could see. If I swish panned really quickly, you couldn’t recognize Michaelle and John, and I wondered if you moved the projector would you be able to recognize the image more quickly? No you can’t, because you have the blurred image in the original shot and you can’t sharpen it up through projection. I don’t show that one much.

Scanning 5 (3.5 minutes, silent, live performance, 1983) was shot in Berczy Park, behind the Flatiron Building in downtown Toronto with David Anderson walking back and forth. The camera follows him then turns upside down and overhead and is projected around the entire room, including on the ceiling. Do you know the game “Monkey in the Middle” where two people are throwing a ball to each other and there’s someone in the middle trying to intercept the ball? Scanning 6 (3.5 minutes, silent, live performance, 1998) was shot in a park with two friends, and I was the monkey with the camera, trying to film the big colourful beach ball going overhead back and forth. This film is projected onto the ceiling.

I also made one called Scott’s Scanning (3 minutes 1999) for Scott MacDonald who brought me down to Upper New York State a few times to perform for his classes. Those were great gigs because he’s one for paying well. It’s a political thing for him. I remember he gave a keynote speech at the Images Festival here saying that any filmmaker who accepts less than $250 is crazy. You’re just hurting your cause by demeaning yourself, people won’t take experimental film seriously if you’re willing to work for nothing. He paid $1000. He liked Scanning a lot so I made him his own version of it. I shot it at the Hamilton College campus in Clinton, New York, and it shows Scott and his student Kyle Harris. I gave it to him and expected that when he showed it he would pick up the projector and move it the way the camera moved. But he said it was too complicated. The same thing happened with my film Animal In Motion (1 minute, super 8 and 16mm, 1980). Scott took three of my films to Europe to show during some talk he was doing, and one of them was Animal In Motion. The first half is all black, except for a clear frame every five seconds. During projection, I ran back and forth in front of the screen in sync with the flashing, so that when I was centre screen, it would freeze me, you would see a silhouette of me for 1/24 of a second. In the second half, each clear frame is replaced by a few frames of found sound footage of a person shouting at the camera, and I shout back at the person while still running back and forth in sync. Scott said he wouldn’t be able to run back and forth and figure out how to do that, so he just showed it and talked about how I performed it.

After six versions of Scanning it evolved into a new series I call Remember Rings (super 8 film performances, 2000-2005). My Peterborough Remember Ring includes a history of Artspace, the artist-run gallery where I showed my films in the Canadian Images Festival in 1983. I show all the buildings that Artspace has been in over the years. I also talk about censorship issues, and how my nephew couldn’t get in to see my show there.

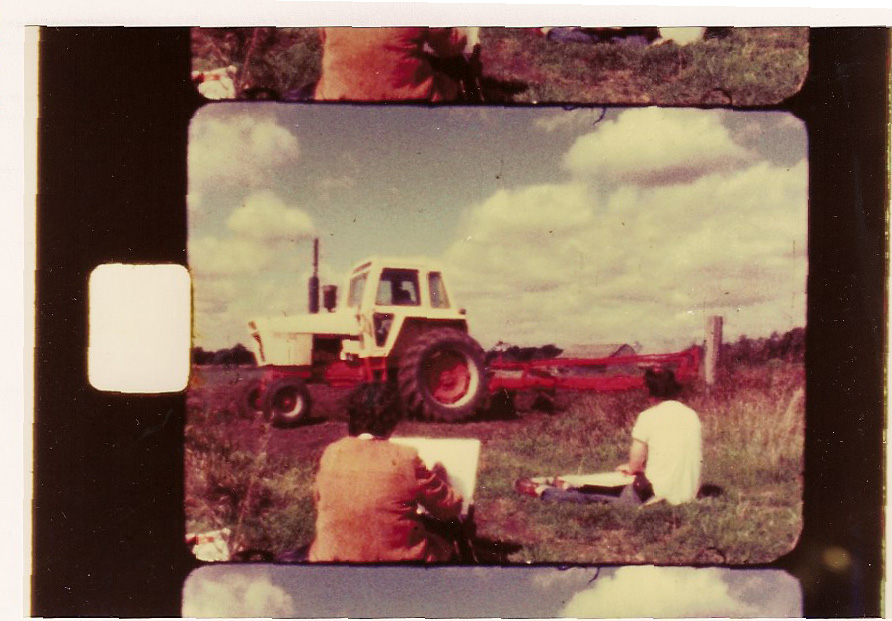

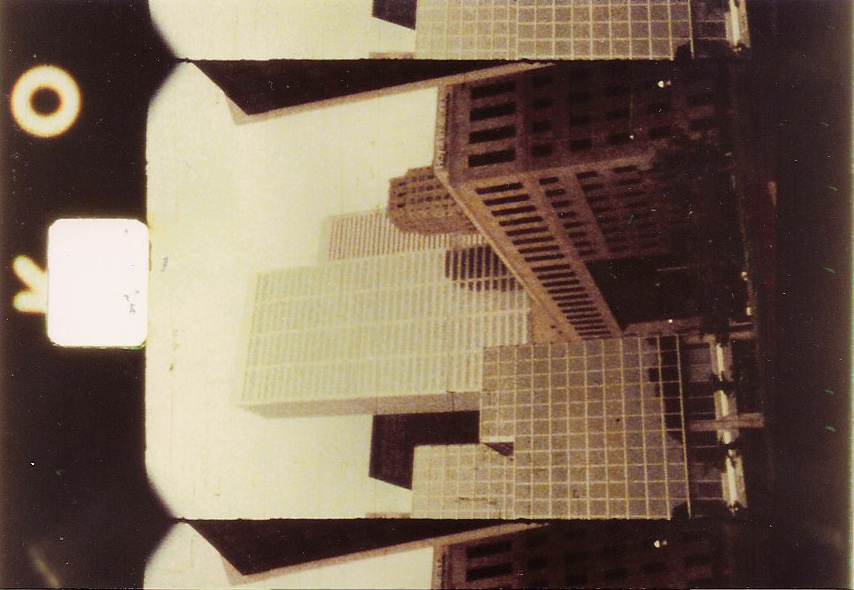

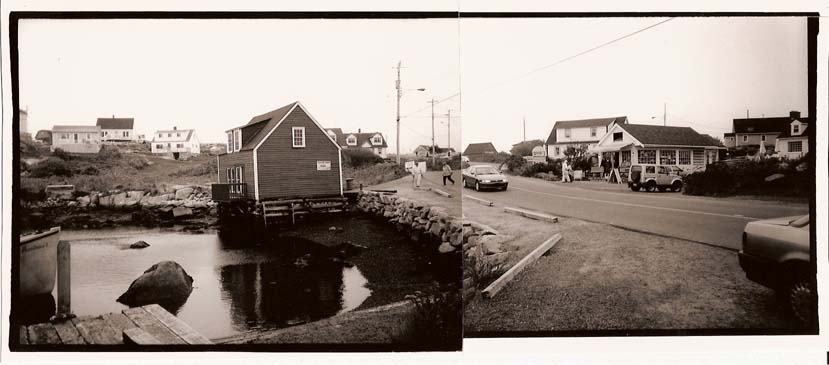

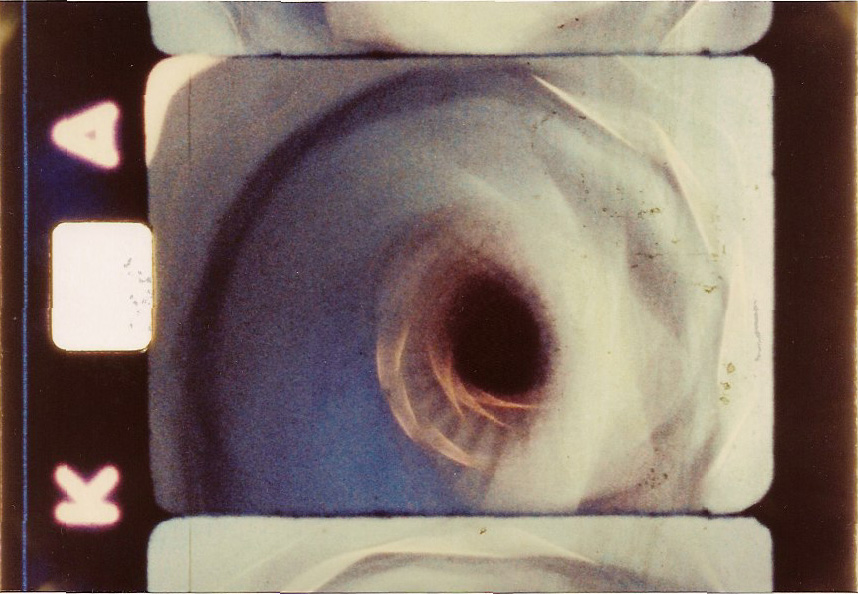

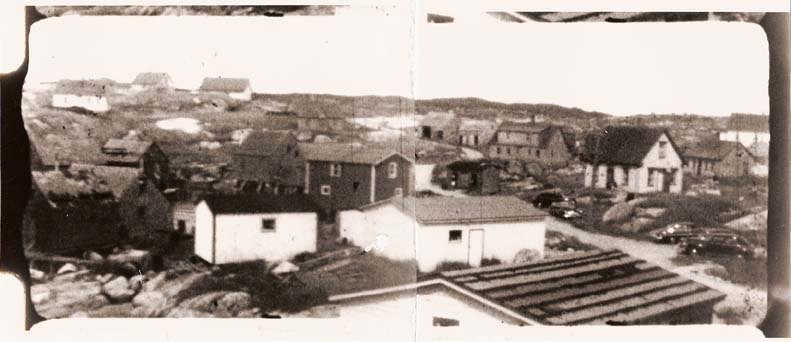

PeggysCove, 1949 – 8mm color film by John’s uncle George Johnston, composite 8mm frame enlargement by John Porter, 2000

Mike: Can we talk about your Camera Dances? Did you imagine they would be a series from the beginning?

John: Yes, but the title of the series changed as I added different films. First, it was “Spinning” films, then “Film Flights,” then “Camera Dances.” They’re my film performances where I perform either for the camera or with the projector. I discovered performance art at The Funnel and started to incorporate it into some of my films. After I made a number of them, I had a Camera Dances show at The Funnel and made a poster showing me in a tuxedo, dancing with a camera on a tripod. I had been interested in dance even before film, along with acting.

Mike: Down on Me (4 minutes silent, 1980/81) is one of your best known films.

John: When I started going to The Funnel I had just been making these Condensed Rituals. But then I started seeing performance art and more chaotic experimental film and it opened my eyes. Oh, I don’t have to make these slick films with their fixed tripod positions and single shots. I got inspired to loosen up and be more radical with my techniques. There was a sky diving friend of Tom Urquhart, and once a year she and her friends would rent The Funnel and show sky diving films, some of them home made. I lived just down the street and would go to see anything that was happening at The Funnel.

After one of these screenings, I wanted to shoot a film that looks like it was shot by someone falling to the earth. The first thing I did was buy a small parachute about six feet across, used for dropping parcels. Not big enough for a person, but a lot bigger than a toy. I wrapped a small, lightweight camera up in the parachute and threw it up in the air, but the image was too shaky, I like abstract film, but I wanted to see enough to make it feel like you were falling.

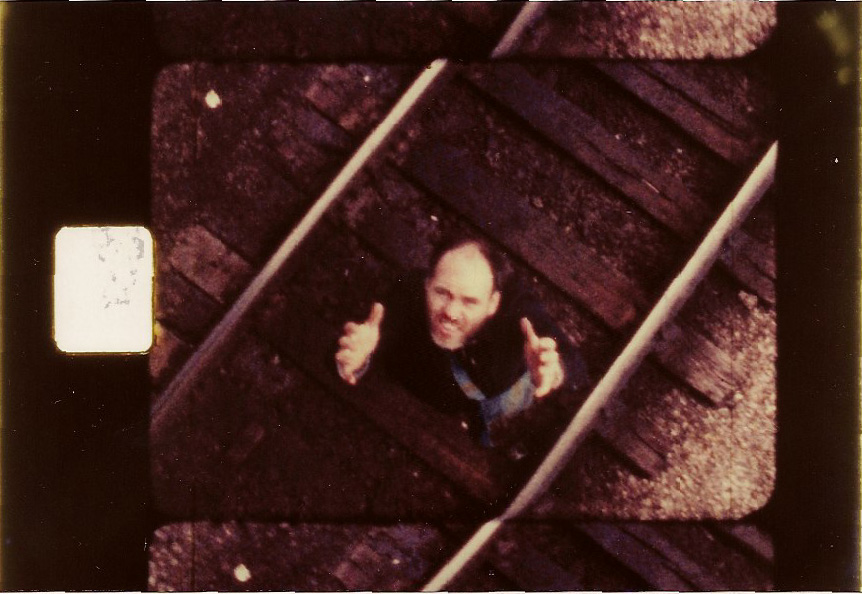

I had been shooting the pixilated Condensed Rituals films, so I got the idea to put the Braun Nizo camera aiming down on a fishing line and lower it slowly from high locations towards the ground shooting at one frame per second. When it was shown, the falling would appear really fast. Last year I showed Down on Me as a gallery installation, so I hung a projector from the ceiling, pointed down towards the floor. People could spin the projector the same way the camera was spinning, so you get this fixed image on the floor. Stephen Niblock was my fishing pole operator, and the first several shots were made from the roof of The Funnel. It was five stories high and we tried different corners of the building. Then we went to the Queen Street Bridge that was close to The Funnel, and finally to the Bloor Viaduct further up the Don Valley, that’s the highest spot. The next year we went back and shot interiors using time exposures, so it was possible to shoot even in indoor stairwells which are normally very dark. I was still working as a letter carrier then, so I knew what office buildings I could use that had good stairwells.

Mike: Can you talk about your Cinefuge series and how it was made?

John: It’s another form of panorama. I was inspired by the last scene in the spaghetti western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly by Sergio Leone where Eli Wallach runs around the camera which is at the centre of a circular cemetery, looking for a headstone. The camera keeps him in sharp focus while the headstones become a complete blur. It was so inspiring that this long, wild, chaotic shot could be contained in theatrical cinema.

Once again I was interested in motion blurring, looking for another way of achieving the blurred movements I was getting with time exposures in the Condensed Rituals. But Sergio Leone’s graveyard scene was shot at normal speed, it was a question of moving the camera quickly enough. When I first tried it at Ryerson on 16mm, I held the camera aimed at me and on a tripod with two legs strapped to my waist. Then I got the idea to attach a super 8 camera to a rope and throw the camera around my head in a circle. I made different versions, the first (in 1974) was only 30 seconds long. Then I started using a finer, less visible line. Cinefuge 2 (3.5 minutes 1977) was made in a gazebo in St. James Park. In Cinefuge 3 (7 minutes 1977) I went out to High Park with a couple of friends, Lori Spring and dancer Judith Miller. I wanted people who were visually different than me, shorter, with long blonde hair. I’m tall with short black hair. I was worried that they would be so blurred that viewers wouldn’t be able to distinguish the three of us. Judith and Lori ran around me, while I swung the camera around my head. The background becomes a blur of colour and motion, while the three of us are still in focus most of the time.

Cinefuge 4 (1979) featured just Judith and I. I realized that I only needed one other person because you could see us both quite clearly. So Judith ran around me while I swung the camera. Then I had a chance to have a commercial shown on The All Night Show on TV. I don’t know if you remember The All Night Show, it was a lot of fun. They were the first ones in Toronto showing old reruns of The Twilight Zone and Outer Limits from midnight to six AM. They were going to have me on as a guest filmmaker and they offered to show a commercial they could run during the week before I came on. I made a one minute sound version of Cinefuge,

Cinefuge 5 (1981), talking about my upcoming screening at The Funnel. That’s why I was coming on the show, to talk about my upcoming screening at The Funnel, my Camera Dances screening! I say to the camera, “C’mon out to The Funnel. It’s a really friendly theatre. They’re all filmmakers, just like me.” That line always gets a laugh from the Funnel people because it sounds like they’re all John Porters at The Funnel. Later I put the last two films together, so now it’s called Cinefuge 4 and 5 (4.5 minutes, sound on film, 1980/81). I took background sound from 5 and looped it and added a sound stripe to the silent Cinefuge 4 version, so now I have sound on both parts.

Mike: Angel Baby (2 minutes silent 1979) is a beautiful, wordless drama which shows your early attempts at flight.

John: It was inspired by Norman McLaren’s Pas de Deux (13 minutes 1968), it’s almost a rip off, it’s so similar. He had a dancing couple dressed in white against a black background leaving a trail behind each of their movements. Angel Baby is the same. In order to simulate flying I had to perform movements lying down on the floor, instead of standing up. The camera was on the ceiling pointing down to a black cloth on the floor and I’m dressed in white. I made a little narrative inspired by the Peanuts character Woodstock, the bird. Often in the strip, the bird would take off from the top of Snoopy’s dog house, and you could see his flying was erratic because there was a dotted line showing where the bird had been. Like Woodstock, I was also learning to fly. I created a little narrative of entering the frame, the first few steps, the first flight, chaotic flying, then more organized, better flying. At the end I fell to the ground. It took 45 minutes to shoot this 2 minute film and it was all done in one shot.

You were at my studio. There were two big holes in the iron I-beam on the ceiling, so I attached a rope and made a swing. I used those same holes to bolt the camera to for Angel Baby, but because the camera was then aimed horizontally, I had to have a mirror reflecting the view to the floor. This made the image upside down, so I had to perform the narrative backwards, and then project the film tail to head to upright the image. That was the main reason I needed a script. It would have been easier to remember if I was performing it from beginning to end. My friend Al Walker was my script prompter. He would say, “You’ve been doing that movement for five minutes, now go over to the right and look like you’re walking.” That way I could do it all in one take without stopping.

Mike: Have you ever made prints of that film?

John: Yes, in the 1980s it was much easier to get prints made. But now my attitude is that I’d rather spend the money it takes to make a print on making a new film. When you’re dealing with super 8, the cost is about the same.

Mike: Are you worried that your work could get scratched or destroyed?

John: A little bit, but I project it myself. I take great care about what projector I show my films on. I want to know their history first of all, and even then I give them a thorough cleaning. Often there is a professional projectionist who has used this projector many times watching in awe as I clean their projector for them. That really reduces scratches, and cleaning and lubricating the film regularly. I’ve shown some films a hundred times without any problems, like Toy Catalogue 3 (60 minutes, sound on film, 1996) which showed at the YYZ Gallery for five weeks. But you do get occasional damage like the burned frame at the Pleasure Dome screening at the Euclid Theatre in 1989. But that’s part of the whole punk, performance art aesthetic. People put on these elaborate performance art shows that they can only do once, and then it’s gone. Why shouldn’t at least some films be like that? Especially the $40 films. You don’t have to be so uptight that they won’t be seen forever.

I remember a film at The Funnel by Robin Lee, he was one of the members there. Do you remember Robin? He did this performance for which he had shot a super 8 sound film, talking into the camera, saying, “When the premiere of this film is over, I’m going to burn it, this is the only time it’s going to be seen.” And he did. He took the film off the projector and put it in a can and burned it in front of the audience. I like that sort of attitude, at least in some cases.

I’ve made 300 films, and a lot of them are very easy to shoot. If I lose one, I can go out and reshoot it. Maybe it’ll be better than the original! In fact, I became interested in this whole idea of simultaneously shooting different versions of a film to compensate for not having a print. It’s better to have two slightly different originals than one original and an identical print. First of all, originals look better than prints, and now you have two of them, but also they’re different! One might be better, another might be more appropriate for some contexts. It makes it more interesting for me because I’m seeing the films all the time as the projectionist.

The timelapse films are made with the camera on a tripod. I have two or three Braun Nizos, and I’ll put them side by side, shooting simultaneously. I did that with City Hall Fire (3.5 minutes, silent 2005). It was a Condensed Ritual about a pyrotechnics performance at City Hall. I went the first night and shot a one-roll film. I thought the subject was so beautiful I went back the next night with two cameras and now I have three versions of that film.

Another example is Town Hall Movie (3 minutes, silent, 3 versions, double projection, 2004). I shot it at an Images Festival screening at Innis Town Hall. I had the camera under the screen on the floor looking back at the seats. You see the audience coming in and filling the seats, and then the lights go down and all you see is the projection beam for most of the film. And then the lights come up and people leave. I had two cameras shooting at the same time, one with colour film, one with black and white film. I’ve even shown those two versions together, I made a multiple projection out of it. I’ve superimposed them, and run them side by side. That’s another freedom you get from shooting different originals rather than making a print.

Mike: Firefly (3.5 minutes 1980) is another camera dance which shows you spinning a small light on a long cord against a black background.

John: It’s directly related to one of my Condensed Rituals, Amusement Park (6 minutes, silent, 1978/79), which is of spinning thrill rides lit up at night. I wanted to do a performance that was like that, but with more control. Like Angel Baby, I’m performing in the same black room, though this time I’m dressed in black as well, and it’s a “Spinning” film too, like Cinefuge. In Cinefuge, I’m spinning a camera around my head, while in Firefly I’m spinning a light around my head. It’s a one-shot film, shot in one hour, at one frame per second with one-second time exposures. The subject is light.

I don’t do much in the way of trials or rehearsals, if it doesn’t work out I’ll shoot it again. I did an exposure test using a candle so I knew where to set the aperture. But when I got the film back there were all these secondary lights caused by the much brighter light refracting, bouncing around inside the lens and re-exposing the film. I received technical advice from Adam Swica, who was working with Frieder Hochheim, my Ryerson friend. They had a movie lighting company called Star Sparks. Adam recommended a light bulb used in car head lamps. It’s as small as the end of your finger, but as bright as a 60 watt house lamp. But because it’s so small and focused, not diffused, you get all these refractions. What you see in my film is not only the actual spinning light, but vertical streaks and light washes in other parts of the frame, all sorts of stuff that were a wonderful surprise. It’s an example I like to give of how accident and chance is really important in still photography and cinematography. I like to allow for and even encourage this as much as possible. One of the main reasons I make these films is because I don’t know what they’re going to look like.

My most recent film Night Sleeper (3.5 minutes, silent, 2010), uses a similar technique as Firefly. I’m dressed in black on a black bed, covered by a blanket of white Christmas lights. Instead of one light moving in circles, it’s a bed of lights that only move a little bit whenever I move in the bed, or get up, which I did often just to create some movement. It was shot continuously for 8 hours, using 8-second time exposures on each frame.

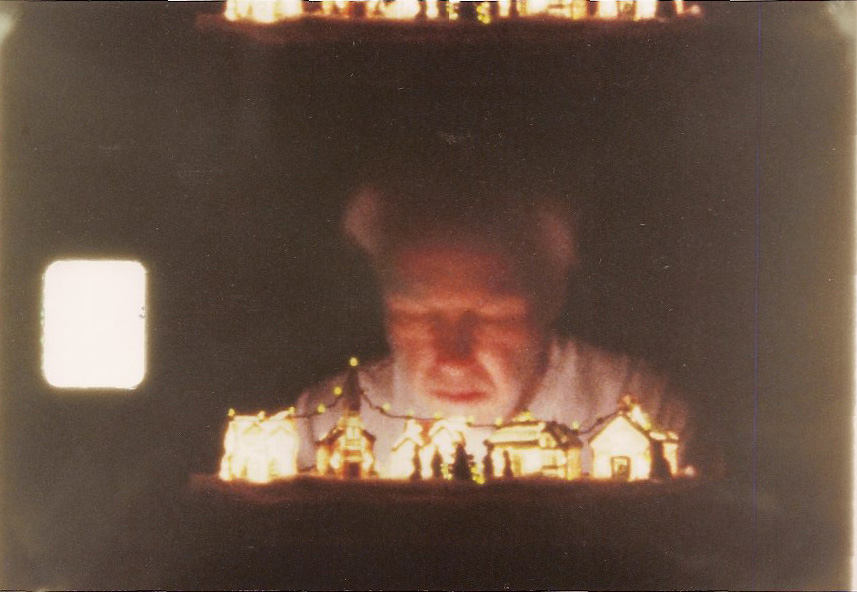

Because I’m doing time exposures, lights at night are a good subject. Even when I was a still photographer at Ryerson I used to like going out at night and shooting the light down the laneway, that sort of subject. So I made a film called Christmas Toy Lights Me (3 minutes, silent, 2006). It shows a tabletop Christmas village with little ceramic shops lit from the inside. I’ve always been fascinated by those kinds of toys and wanted to make a film about them. Because the lights were so small and dim, I added a string of toy lights to the tops of the houses like Christmas decorations. The camera is aimed at this table top display and I sat behind it, using this very weak light to illuminate my face. I had to keep my face very close to catch some light, even with these long eight second exposures. It’s a one-shot Camera Dance, and a self-portrait.

I like shooting my studio films late at night, even all night. You don’t get people calling you, there’s nothing else to do anyway, and you’re not missing a nice sunny day. Shooting Christmas Toy Lights Me I got sleepy sitting there, there’s even one point in the film where I close my eyes and nod off. Then I thought I’d like to make a film of me sleeping, and that’s how Light Sleeper came about. I had the idea for three years, then when I needed to make a film for the One Take Super 8 Event I decided to do it. Anyways, I think I’m going to leave now, it’s going to be dark soon.