Notes on a talk by Simone Moir at Centre of Gravity, June 2, 2013

Seat

When I come to this room I’m reminded of my train travels in China. You can buy two kinds of seats: hard seats and soft seats. The hard seats are just planks of wood. As we spend time here in meditation we really get to know our seats.

Kalamas

Tonight I wanted to talk about digesting the dharma. This community gets a lot of dharma, weekly dharma talks, it’s quite a banquet. I wanted to reflect that back to you a little bit. Why not turn to an early text, one of the first talks or conversations the Buddha had, called “To the Kalamas.” The Kalamas lived in a town well situated for travellers, a main artery that brought many seekers and truth tellers. But whose truth to follow? How to choose from amongst them all? This is the question they brought to the Buddha who didn’t exactly give them the answer they might have wanted. He took an experiential and experimental approach to their question. Instead of believing in a set of values and doctrines he said we had to test and examine experience for ourselves. What are the results of these actions?

What should I do next? What’s the right way to respond to my life? A couple of weeks ago Michael suggested that when one of these questions arose we might try out a response, and examine it. Test it. How are we doing with that idea? How are the try outs?

Parents

Humans need to be cared for a long time. Western cultures offer this model: we are parented for twenty years. And then we pass on this job to other people called teachers. My teacher, my parent. Oh hi dad, it’s you again. Some fathers are books, or movies, or friends. In this culture we are busy converting people around us into our parents, so how do we learn to trust ourselves? Can we trust our results, do we know how to read them? Often we prefer to follow someone who’s already done it, been there. Which leads us back to the question of the Kalamas: who do we trust, who do we choose? How often we long for a solution, a strategy: if you follow these steps, you’ll get these results. A life with a warranty, with guarantees, markers and guideposts.

Risk

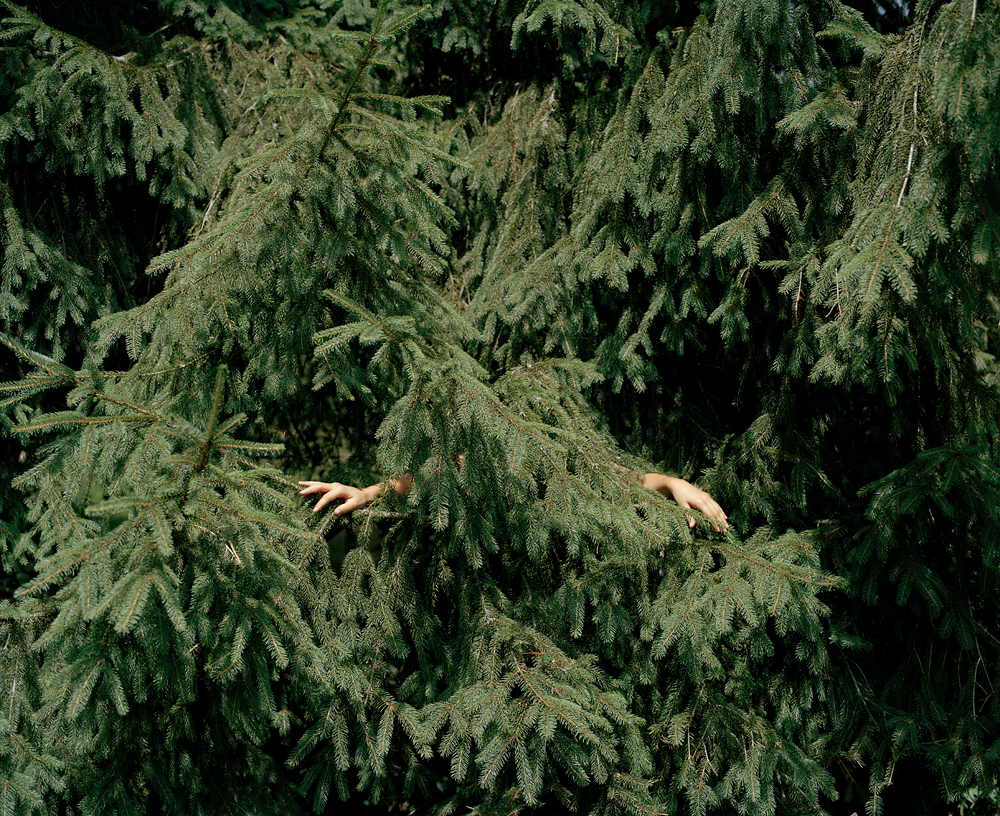

The Buddha offers us some maps in his teachings: the four ennobling truths, the three pillars. But in the end he insists: trust yourself. This experiential approach means taking a risk. It means leaning back into your own taste, touch, smell, hearing. It’s a risky business, we don’t get to stand back and calculate, we have to plunge in. The habit pattern is to be forever rehearsing for our life, then getting frustrated when it doesn’t conform to our fantasies and projections.

What’s for dinner?

We’re going to a restaurant that has been reviewed by thousands of patrons for many years. Our menu tonight is an enormous dish: vast, profound, fathomless. It’s also simple, clearly stated, easily understood. At once delightful and terrifying. It can calm and soothe, but then at the next moment pull the rug out from under us, unsettle everything we thought we knew. It matters to us because it’s personal but at the same time it doesn’t belong to us, it could apply to anyone, anywhere, in other words: it connects us to each other. Oh, you too!

The dish I’m describing is the dharma. It’s been served up by the Buddha and many others over the years. So many have worked to map this path. But tell me: how does a snake eat a lamb? What are the conditions for digesting the dharma?

Dharma

What is dharma? In Hindu it means law, but in Buddhism it means the truth. Even: particles of truth. There’s a dharma of business, a dharma of parenting. It’s a kind of system. Buddha’s teaching is described as “genuine dharma.” It usually combines these three qualities: it is presented with personal and theoretical accounts and related to history. It can be joyful to hear because it can make sense to anyone. It avoids extremes: not all good news or bad. Balances god/faith and nihilism.

Dharma has a foreign quality to it. It doesn’t fit into our regular thought patterns. Most of our mental work remaps the world so it points back at me. What does this have to do with me? The dharma disrupts this.

Identity Kit

We never know how far it’s going to go. I thought I’d give up a few things and have a peaceful spot in my life. But after a few years it wasn’t enough, do I now have to become homeless, how much further do I have to go? The dharma is not part of my new identity kit, my new design scheme. It’s bigger than my personal calculus. And it’s something you do, it’s something you have to put your whole self into. The ways we usually construct an identity (career, family, art), the control and creation: the dharma doesn’t allow us to build a self improvement project. Though this is an important starting point, it’s what gets us into the door. Some kind of self improvement project. I want looser hips, toned abs, to be free from doubts. We come in through that door and find some answers, but then the dharma melts out certainties away. We want to be certain, to have a home, to stand on solid ground, even though, especially because, our experience is shifting all the time.

Traditionally the dharma is thought to be universal, a personal understanding that is applicable to all beings. It’s different than Jungian analysis or astrology or any other personality mapping system.

When we are confronted with a meal this size, some fear might arise. We may not be able to keep our distance, to choose what we want. In order to test drive the dharma there’s a lot of commitment involved, and I think we all have questions around commitment. And we can’t just drink it down, it’s not like a degree that makes us an expert. The more we know, the less expert we become. One of the questions that comes up for me eating this fathomless meal: what if I don’t like what I’m becoming, can I go back? Can I change myself back? Where did I put those magic beans? Will I ever be the same again? And what about all the things I have to give up? How should I relate to what I’ve heard? What teachers do I trust? In the past year we’ve heard a lot about Michael Roach and John Friend, high powered teachers who finally had their plugs pulled. So many felt betrayed. It speaks in part to our wanting to trust, to be part of something larger than ourselves, and to seek out parent substitutes to show us how to get there.

How do we find the right teacher? And how do we leave our teacher, so that we can trust our own experience? Let’s put it another way: how has the dharma changed you? What have you given up? For me, I used to feel that along with my comrades we were reshaping the world with our righteous understandings. Now my point of view is not so fixed. What kinds of challenges have you been facing?

What’s Changed?

Centre of Gravity is in its initial blooming phase. It’s high unusual to have teachings every week. Podcasts, videos. There was an idea to double down and offer Thursday night sessions. Is this what the community needs? How is digesting going on? We’ve just “finished” a text by Shantideva, what have you retained from that? What is happening for you when we go through these teachings? Where are they now – in your life – where are they? Are they a list, a practice, what have you retained from them? What sticks to you? What’s changed? (Partially digested meals keep us child-like. We remain lost, stuck in comparisons…)

I was recently in Mexico, and couldn’t help noticing a Starbucks in Cancun. If you open it, people arrive. Does the community need a Starbucks? Is the fact that people are lined up for coffee prove that this is what people needed? What does the proliferation of this experience mean? Does this community need more teaching?

Bellies

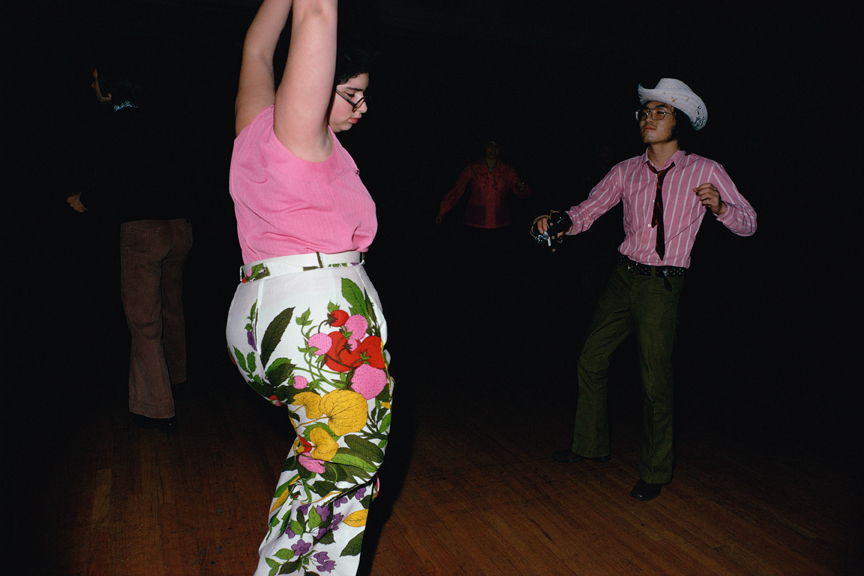

I’d like to turn to our bellies now. Could you find a partner in the room, if you don’t know them, even better! For four minutes Person One will talk about a meal you’ve had. The other person will listen in silence. Then the roles reverse. How did you eat a meal? Then: is there one or two words you could use to summarize your experience? The way you eat is also the way you absorb mental information. How do I learn? How do I navigate the outside world and the inside world?

My food preparation is detailed and careful. But eating happens while cutting my movie. I don’t taste the food. I’m just getting through it. I’m led via sensations to feel hungry, to prep the food. But then I just throw it back. Eating makes me hungry somehow, it’s tasteless. What’s valued instead is velocity, speed, I want it to be done, I want it to be over so that I can finally do the thing I really want to do (no idea what that is). There is always a promise lingering around the corner, and I keep the promise alive by not tasting what I’m eating. I am a kind of slave to this promise, to the faith this promise represents. And speed has its own thrill, the feeling of being on top of something (instead of being in the experience, being on top of it, so that it can’t hurt me. Why the default imagination of pain, instead of pleasure? Old grooves, old patterns).

I remember a moment with Stephen Batchelor. He had very generously gifted me a cd with ten hour-long talks on it, the full course he had dished in Australia the summer before. He and Martine (his partner) were going back in a few weeks. “What are you going to talk about when you go back?” I asked him. He looked at me quizzically. “We’ll give the same talks of course.” Oh. Right. We need to hear the same talks again and again. Stephen and Martine have been giving variations on the same talks for many years. It’s so important, and it cuts against the deep habits patterns of our culture which is forever hankering after new informations, disposable factoids. Instead, the Batchelor talks are like sitting meditation. (imagine if you could sit only once, for one hour: I got it! Never have to do that again!) We sit each day because the practice creates a counter groove. We need this reminder again and again, we need to live the reminder, to become the counter groove.

Eat

Before I breathed for the first time I had already eaten (inside my mother). I was breaking down foreign substances and assimilating them. As a baby I needed to find, latch, suck, bite, chew. A lot has to happen before food gets into the acids of our guts (Is that why we love smoothies? someone has already chewed our food). The way we eat, the way we break down food, is the prototype for how we receive thoughts, impressions, friendships, love. For how we digest all experience.

The Buddha has a parable about digestion, about the way students relate to the dharma. There are four pots. Pot One is a clay pot with holes. You pour something into it, but it flows out. In one ear out the other. Pot two has cracks. It retains teachings for a while and then they seep out. Don’t know how to hold onto what you’ve learned. Perhaps you’re still shopping around for teachers. Lack of appreciation? Pot three is full of water to the brim. There’s no room, you’re full. When you’re full it’s hard to accept someone’s offering, no matter how fine. These people already know, they might compare dharma to what they already know. They can be collectors, filled with intellectual curiosity. Pot four is an empty clay pot. Beginner’s mind. The whole body of the pot is like an ear. The whole surface is available and present.

We can think about these pots in relation to how we digest. Are we only in this room with half an ear? Are we ready for another talk? The Buddha says: we need to immerse ourselves. To become our own authority. Say good-bye to mom and dad.