Notes on two movies by Dirk De Bruyn

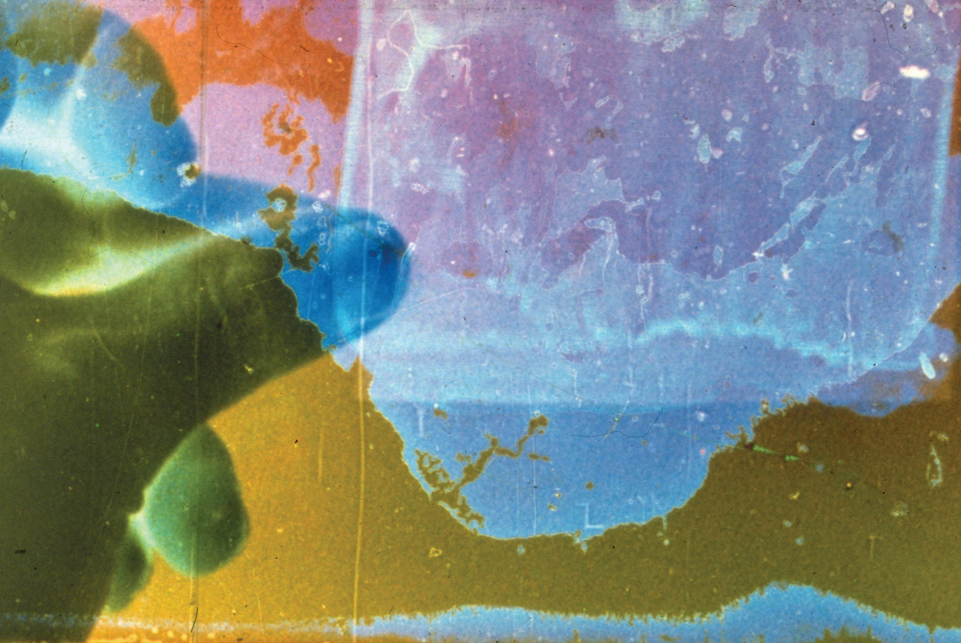

As soon as Traum A Dream begins I relax a little knowing it’s Dirk. There’s no mistaking it, as soon as the first few frames flicker by it’s like picking up the thread of a conversation left hanging a month ago, a year ago, how many years ago now. The way we express our interiority is manifold, a gesture of the hands, the amount we drink (or don’t, so much of who we are lies in what we don’t allow ourselves to do), but also here in this frame by frame rhythm. I feel Dirk in his choice of colours, the bursting, blooming colour fields applied by hand, part of a hundred sketches laid onto emulsion. A dance of colour meets me when I watch this again and it’s like hearing him breathe a story beside me, it’s him, his Dirk-ness is all bound up in this knowing.

He came from a place that reveled in form and shape, in the pure beauty (can anything be pure anymore?) of light striking emulsion, a cinema of Richters and Ruttmans they used to call “absolute” before we knew better. “Absolute” was another utopia we had to set aside to make room for the lives we were actually living. Dirk never used his movies to shrink himself from the world, to cover himself over with the absolute so that life couldn’t touch him, on the contrary. His movies, and this one in particular, are all about touch.

The way his colours arrive ratatat, one replacing another in a great heave and rush, tells me something about his joy and excitement in expression (It’s you! You’re here!) but also carries with it a sadness because it’s not lasting, is it? It’s rushing on by and never will again, not this way. If it’s human it doesn’t last, that’s part of the song Dirk is singing here.

This little ragged bumpy ride of a movie reminds me of Frida Khalo’s paintings, and the way John Berger described them, as if she was painting on her own skin. “Eyes you remember only if you shut your own.” And especially this: “But the will to share pain is shareable. And from that inevitably inadequate sharing comes a resistance.”

This body is wounded, torn and damaged, and he is trying to bind the wound with these pictures. These pictureless pictures. This colour. But he can’t help showing the wound as well. He returns to it over and over, but it’s not altogether distinct, or clear. It is, above all, not a story which can be told and revisited, instead a mound of sensation, a blinding hurt. This is as much as he can show us, it hurts him to get this far and it’s not enough. He knows it’s not enough too. At the end of the movie the jumble of signifiers, the torn scraps of language, have congealed in order to form a new poetry. This is what he dares to do: he shows the confusion in its most raw state, before there are sentences, when the mouth can only groan or sigh, when there are colours, not even shapes, not even something that distinct, that’s how deep the wound goes. He shows us this world inside the body, where the pain began, and shows how he moves through it, shuffling the parts, cycling and recycling, whispering into his own ear, urging himself not to get stuck there, to emerge, and at last, in a few winning strokes at the end of the film’s interminable six minute stretch he arrives at a memory of childhood which he’s not allowed to reveal. Especially not to himself. Never that. On the soundtrack Dirk’s voice whispers, “He began to remember what had been taken before you, a secret from before, before he knew himself.”

Rote Movie

I remember seeing this while Dirk was working on it, while it was a collection of strips hanging limply from the walls. There was hope in the room, and these hopes were being taped together piece by piece. And when it was finished, somehow, we were in a van heading for Ann Arbor and watched it on the State Theatre’s impossibly large screen and were thrilled. The private thing, the small thing you rub between your fingers to light your way, sparks up to become us for a moment, our story. And now a decade on I’m watching it again on television so I can write some of these words, but it doesn’t belong here. There is not a place for everyone on television after all, this is what Dirk’s movie is telling me. There are some feelings which can’t be televised.

It’s handmade for one thing, scratched and markered and rough, how did he get it to look so rough? It’s like shaking hands with someone who stumps telephone polls in for a living. And somehow this roughness is married to the cine-projector, they are relying on one another, it’s no use trying to imagine it as a video, on television, because it’s invisible here, I can’t make out a thing. Only when it lights up onscreen does it appear at all, and then it’s all I want to see. Why is that?

I think there are some lives, some feelings, which are made possible by chemical analogue cinema. Dirk’s movie, for instance, is a modernist text about nostalgia (the wounds of returning), something is missing (his family) and so his restless journeying, shown via hand-drawn rotoscope as his sketched out car ventures along the highway, leads him only further afield. On the soundtrack, Dirk’s familiar voice whispers, inner monologue and conscience, which he told me later he’d copped from the Canadians who were interminably yakking through their own movies, who used their movies as a pretext for chit chat, but here it appears every bit his own. These longings and hopes are part of another time, there are still I-wish-you-were-here’s. There are still regrets of course. But not these regrets. Not this family. This is a body born in the light of this time, part of a machine which is already in its last moments now, relishing its final, fatal bloom in rote movies like this one, an elegy for elegies. Another last picture show.

New lives will have to be invented for the computer. New kinds of loss.

One day someone will be forced (out of heartbreak or distress) to look back, and they will find this movie which will be able to speak to them about the way people used to fall in love, the way family used to appear, the way someone got their whole body up into a machine and projected it across a public, from behind their backs, so the light was picking them up along the way, projecting them all up onto a screen where it was our story again. One day this will be our story again.

From a letter by Dirk, Nov. 1, 2005

re what’s going on here… I gave a little intro to my program, which preceded yours, to say that since the mid 90’s the public face of local experimental film in Melbourne is dead and that my program, in a way, was a response, dealing, scavenging, surviving through that reality. It was good for me to do because it put to bed my mourning about this.

Also, there was an Experimenta program on before which was not a Cinemathque program, with a lot of those smarty pants, style people, who went straight down for drinks and did not bother to turn up for what followed… which only highlighted the point I made. The films/videos in that program were not well received, Adrian Martin wrote a damning piece about it, along the lines that there was only superficial at best innovation. Anyways, who cares about the elastic opinion machine? You had a small, committed audience

re the st paul thing… One person was talking about the black spaces between film and it made me think that the afterimage that 16mm frame leaves in that shuttered space is like a bruise that the next image builds upon or palimpsests over, very different to the wipe/erasure mechanism of video.

Marcus and a few of us are going to re-visit Frampton over next month, especially Hapax Legomana, especially as a response to your comment, to unpack and inspect its structure.. as we both embark on longer films/videos. That’s how it all continues… clandestine, tentative screenings here and there in cafes and lofts… well be having another look at Amerika as well.

A further elaboration by Dirk Nov. 8, 2005

Outside the Outside

In the late fifties my welcoming aunt toured my nonplussed newly arrived parents and I proudly around the Olympic Games sites from a few years before, stating in front of the old Olympic Swimming pool that now Melbourne had made it. Australia was now part of the world. Already as a small boy I could recognize the folly of her posing. This did not make sense. Clearly, the carnival had already left town.

By 1975 I felt what my aunt felt. I thought that the culture I had now grown up in could participate globally and film was it. It was in the air. A colonial cast could be broken. I had seen packages of Experimental works at the Melbourne Filmmaker’s Co-op where I had been hanging round, working on the front door. There were the meta-texts of Brakhage’s Dog Star Man, Mekas’s Lost Lost Lost, Thom’s Sunshine City, programs from the London Film-Makers co-op and an initial introduction into the work of Maya Deren. The local work of Brian Jones, Jim Anderson, Peter Tammer, Nigel Buesst, Michael Lee, Jonas Balsaidis, Lindsay Martin, Solrun Hoaas and the Cantrills and their film-notes opened a door to being taken “seriously”. It was also the time of a first encounter with a sharp and perky Hollywood Dave in the co-op bio-box.

I had cobbled together a number of unpublished films; one processed largely to sepia in the bathtub, another an edited story about my friend Dave, a clock and an axe and a re-cut series of found ads assembled at Sydney University’s Film Club. The AFI’s Experimental Film Fund beckoned. After many false starts, I could play in this game. It was only a matter of acting on your ideas and doing it, with or without funding.

How do you connect such an initialising time to the present? So much water has passed under the bridge. The Experimental Film Fund moved to the AFC, changed its name and unfortunately no profile for film art emerged at the Australia Council. At the AFC the main game constructed, understandably, a national film industry with flagship features and funding morphed and split through various forms as the experimental was ushered into its own ever-diminishing funding back-water.

With such discounting one had to confront the reality that we were not participating in any official dream but more of an outsider self-sufficient, reflexive cottage shadow of the official story. This was no big deal at the time as it seemed in keeping with my station as a wog in what was purported to be a classless society and it promoted a kind of “Everyday versus Spectacle” take on it all. Everything was still possible as long as you pulled it out of your own garage hat with a good old Oz DIY disposition of making do. I was not alone in this boat and, after all, there was a global scene for this film art stuff that you could identify with.

Such a discounting spiral winds through a few turns before it settles to its still point, where the practice dies. Through a presentation of my recent work at a Melbourne Cinematheque screening under the title of “Ancient Damage” I was able to unload publicly the burden of a decade worth of this mourning for an abandoned practice. This witnessing was prompted in part by an audience question at the 2005 Vital Signs Conference, a conference briefed to take the pulse of a New Media art practice itself perceived to be under siege. The questioner wanted to know what had happened to the high level of activity in experimental film from a decade earlier, activity that seemed to have abruptly disappeared.

What had happened, unfortunately, via a particularly graceless changing of the guard at Experimenta at that time, was, through an itself commendable advocacy for New Media, the erasure of any public profile for local experimental film. This move from the central embrace of the new to an eventual centrifugal pull to the margins seems like a repeating account, the wheels within wheels inside our media culture. It is a particularly Australian tradition founded in that Terra Nullus moment when on arriving, those members of the first fleet planted that British Flag on these shores and declared that there was nothing here.

I was at that Vital Signs conference to present a paper to stress the ongoing critical and innovative health of an Experimental tradition in Canada that I have experienced as a kind of invigorating parallel universe. It was also about trying to get the message across to the New Media cohort, once again, that the non-linear tradition passes through the experimental and is enmeshed into the “new”. I don’t think anyone got it. They were somewhere else trying to hold onto what they had.

That is how this script has repeatedly unfolded in this country from those early 1975 moments, with many disappointments, setbacks and even betrayals that finally have both crippled and strengthened me in terms of my own work. In this I merely repeat my parents’ resolve in always running to a receding horizon of belonging and safety. Coming to Australia itself had set that ball rolling.

Returning recently from the energy of presenting an Interactive at the “Out of Time” Conference at the University of Minnesota and a screening of works in an historic Dutch East India Company warehouse in Rotterdam I re-entered, jet-lagged, the emptied landscape of Spencer Street Station on a Saturday afternoon. What was I doing here?

I realize that I remain marooned outside any promise that the now mythical mid-seventies illuminated. I brace myself for another round of a futile struggle; not that earlier construction of a settler homestead, no dissenting Glenrowan residue, nor a heroic search for an inland sea or even marginal participation in a national film industry. Tricked by a quirk of history and place, I must continue minutely to search and eke out a space for my own art to exist in my own country. It is rumoured to be found somewhere between the carnival and its hollow trace, it is pockmarked with the ancient damage of denial and it presses me to remember, through some fuzzy local Aussie logic, to Never say Never.

Originally published in: Synoptique, March 2005.

Material Damage: The Films of Dirk de Bruyn by Steven Ball

1. Material

The low grain of the sound of Dirk de Bruyn’s voice weaves through many of the films he made in the 1990s. Mike Hoolboom characterises this voice as providing an “inner monologue and conscience”, a mode that Dirk had “copped… from the Canadian filmmakers who interminably used their movies as a pretext for chit-chat” (1). But Dirk’s employment of a device favoured by these singer-songwriters of Canadian experimental film (Hoolboom himself and the likes of Philip Hoffmann, Kika Thorne, Steve Reinke et al.) is, as Hoolboom observes “every bit his own”, and as distinctive in the texts it narrates as it is individual in its timbre. Dirk’s voice rarely supplies the relatively cohesive narration that one usually finds in first person cinema. Rather, it combines fragments of phrases, a series of hints in a fluid syntactical, semi-random, found poetic flow.

Films like Understanding Science (1994) and A x Canada (1995) often share the voiceover narration with Dirk’s immediate family, but in Rote Movie (1994) he goes solo, placing himself behind the wheel of a car, reciting words reflecting on his feelings of exile, distance and loneliness: “walking through a landscape alone”, “gypsy”, “victim”, in a slow vaguely depressive incantation of unintelligent memories.

By Traum a Dream (2002) the unintelligent memories have become distinctly more sinister. Samples of found footage suggesting memory and repression vie chaotically for attention with Dirk’s voice reciting repeated words and phrases, punctuated by splutters and coughs, as though attempting to wrest some meaning. This meaning comes at last with the final sentence dragged out phrase by phrase in the third person: “he began to remember what he didn’t want to remember, what had been taken from when before he knew a secret of before he knew himself”.

The voice anchors these films in a personal, subjective realm that avoids direct expression or communication in preference to a combination of syntactic tics and diaristic “notes to self”.

It is a melting pot of more than just fragments of images, there are clusters of things, ideas, sounds, words, that swim in and out of your attention. I wanted this film to be a dense multidimensional collage of automatic writing, sound poetry and abstracting strings of images. (2)

This statement of intent is a key to Dirk’s films. These restless, hybrid home-made animations typically cut together a pixellation driven, fast-forward clash of graphical images, hand-drawn, direct-to-film text, erasure and manipulation of found footage; ideas are just grasped before successive fresh images and repetitions move through another set of visual experiments, leaving the signature movement trace of a gesture.

Rote Movie is made from images of road signs, cars and billboards, the passing landscape rendered as elegantly simple rotoscope drawings, reprinted and texturally manipulated filmic images, and the inevitable repetition of countdown leader. In subsequent films Dirk has been refining the more associative and illustrative relationships between image and sound of Rote Movie, into more abstracted forms, equally personal and subjective but more dynamically reflexive.

One ingredient in these films is found footage; variously operating as a texture, a signifier of nostalgia and memory, an index of the medium (academy leader, etc.) and an occasional oblique commentary. Usually this sits within the repertoire of effects and manipulations, but the recent film H2 (2005) is an enigmatic exception. Cut down to 16mm from a 35mm trailer for the movie Shaft, the slowed down voice, gunshot explosions and lsaac Hayes’ iconic music become barely recognisable and monstrous. The arbitrary framing provides glimpses of the edges of faces, fleeting urban scenes, partial text, all rendered in cyan negative in a kind of psycho-dramatic abstraction, all the more unsettling than Gordon Parks’s originating gangster populated dystopia. It is a reminder of how, by simply repositioning the frame, extant material can be transformed.

In the 2nd Hand Cinema films (2005) there is a more deliberated manipulation; clear snatches of the retro signifying veneer of found footage heavily worked over with hand colouring, dyes, drawing, shapes, semi-random text, images of faces merge with more and faster movement, stuttering voices, scratching, the sound of counting, like so much cognitive excess.

Analog Stress (2004) combines reworked and reanimated found industrial and discarded personal footage into something like an audio-visual/filmic version of a scraped back advertising billboard; multiple layers of tattered posters ripped and covered in spray paint, sinking into decay; a chaotic concrete soundtrack reconstructed from scratches, pen marks, Letraset strips and found music and phrases. It is a restless and arresting abstract description of excess and distress.

These films are the stuff of the superficial sublime; palimpsests piling surface upon surface, scraping back here and layering there, a process that obscures as much as it reveals, but is purposefully obscure in its superficial dimension, not a direct obfuscation but a reproduction of obfuscatory states.

And now back to where I started, the grain of Dirk’s voice reverberates with Australian-ness as the laconic burr locates the accent. Critical references to Australia are ironically peppered throughout these films. The references to “never-never land” in 2nd Hand Cinema, the sampling of “the only way we can give an Australian picture international appeal is to make it Australian” in Analog Stress, speak to the irony of Australian cultural self-perception, the expedience of side-stepping the question of exactly what is “Australian” while continuing to invoke the mantra of Australianism. UnAustralian (1997) contains one of Dirk’s more direct comments on this condition, as archival film of Dutch migrants to Australia is juxtaposed with The Seekers song, The Island of Dreams. UnAustralian was a multi-media performance collaboration between Dirk, musician Nicole Skeltys and myself in which we explored the shifting signifiers of Australian-ness and its cultural and political insecurities and paranoia.

2. Damage

UnAustralian was conceived in the heady wake of the Melbourne culture wars that followed Creative Nation (3). Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating’s 1994 reforming cultural agenda sought to ride the then new digital media along the “Information Superhighway”. On the face of it Creative Nation’s drive was an idealistic call to push Australia into the next century, conflating political and capitalist economic expedience with communications media which would now determine models for media art. As a wide ranging, interventionist, deterministic and top-heavy cultural agenda many government agencies took this as a cue for their own visions of permanent cultural revolution. In its idealistic embrace of the new over everything else, some of the works manifested under this regime resembled digital new age metaphysics (such as promulgated by the likes of Nicholas Negroponte [4] and Michael Heim [5]), embracing escapist dreams of networked consciousness, distributed beings, simultaneously leaving the twentieth century and the fleshware of the human form.

In the mid-1990 media art front runners frequently produced works underpinned by fantastically synthetic, voguish notions of disembodied consciousness and artificial life; artists obsessed with escaping the body, creating new life forms or virtual utopias (examples might include those often favourites of the funding bodies like John McCormack, Martine Corompt and Patricia Piccinini). Furthermore digital media art was usually expected to be “interactive”, in the sense of demanding the viewer’s active, immersive determining engagement with the works which in some cases became like little virtual worlds. There was the illusion of self-determining life extensive of the human, a kind of artificial after life in which to escape from the grime of everyday material reality from the tiresome burden of history, and to sublimate those painful collective memories. It wasn’t so much that the artists were burying their heads in the sand, more that they were flying at such altitude as to no longer know where the ground was. Australian media arts seemed to be driven by an aggressively “new world” positivist idealism, unwilling or unable to broach ideas of failure, decay, self-doubt, a neo-conservative evangelical agenda.

The new world would be culturally determined and the individual socially constructed, while conveniently forgetting the reality of life in the physical body in the material world, the inevitability of age, decay and death, the immediate effects of unpredictable weather, earthquakes and tsunami as material life goes on and confronts the very real physical results of conflicting idealisms in Manhattan, Kabul, Bali, Baghdad, London… Life is not lived in the world of the ideal universal but in the here and now of local material conditions (6).

The reason for these speculations about the state of media arts in Australia is not to suggest there has been a wholesale conversion to neo-conservative new media idealism, or that Creative Nation has been a fait accompli, or that there are no longer artists making work that is non-idealistic, critical and dealing with the tangible. My point is to suggest that there is a direct link between cultural production and prevailing ideologies, to argue for an alternative to idealism and the critical efficacy of a materialist approach. This locates the relevance of Dirk’s work within a cultural context that might argue that a materialist film practice is anachronistic – an engagement with the material world is fundamental to existence. A projected new media future and other idealisms are not sustainable in the long term. Digital media is itself just as subject to material decay as analogue forms, a fact that anyone who is now experiencing the reality of the lack of digital media longevity with corrupted data on CD-ROM or DVD and crashed servers will testify to: entropy is the revenge of the material. In recent years there has been an investigation of the raw “material” properties of digital media, such as in the “glitch” work of the likes of reMI and Billy Roisz from Austria and Bas van Koolwijk from Holland. In Australia a more materially forensic approach to the digital movement image is being investigated by Daniel Crooks. Within experimental digital practice there is a return to a search for the material, to make visible the essences of data disturbance and to visualize structure and process.

Traum a Dream

In this “post-digital” context, Dirk’s concern with materiality and physicality is not simply a political act of defiance against the lingering ghosts of digital idealism. Experimental Film is a direct working theory in practice (7) and in the course of its history practitioners have worked the genre to various ends and effects. For example: in the deliberate strategic distanciation or alienation of the viewer (Peter Gidal), as poetical expressionistic abstraction (Stan Brakhage), and through the propelling of the viewer into direct physical response through extremes of effect (Paul Sharits). Similarly, Dirk’s practice is urgent and key right in its relationship to contemporary media culture. It locates itself in the stuff of the everyday and the layers of personal experience and history; it acts as an exorcising desublimation with the shifting associations of the present. It is dialectically opposite to a preemptive or idealistic imagining of the future. Its self-evident physicality is both trace and symbol of tangibility. Analog specifies that emphasis, Stress, like Traum a Dream, suggests something psychological enmeshed in its very fabric.

These films are direct theory in the processes of the material working through the symptoms of damage, the production of living signs, neither representational, metaphorical or symbolic. In their stress and distress they materialise a relationship between the restless abstracted flow of sound and image trace and more psychic disturbances. They concretise the possibility of a direct connection between lived experience, memory, the physical processes of making and the experience of viewing. There is an inscription of conditions that are conflicting and abstracted. Viewing can become a restless, nervy experience producing cognitive conditions that share the symptoms of some of this dis-ease.

© Steven Ball, July 2005

Endnotes

1. Mike Hoolboom, “By Hoolboom: Notes on Two Movies by Dirk De Bruyn”, Synoptique March 2005.

2. Dirk de Bruyn, Understanding Science program notes, Scratch Film Festival, UWA, Perth, 1997. For this and more writings and information about Dirk de Bruyn’s film work see Dirk de Bruyn, Melbourne Independent Filmmakers.

3. Creative Nation: Commonwealth Cultural Policy, October 1994.

4. Nicholas Negroponte, Being Digital, Coronet Books, London, 1996.

5. Michael Heim, The Metaphysics of Virtual Reality, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1993.

6. For a sustained argument about the distinction between old and new world ideologies and idealism versus materialism in culture and global politics see Terry Eagleton, After Theory, Penguin, London, 2003.

7. See Edward S. Small, Direct Theory, Experimental Film/Video as Major Genre, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, 1994.

Steven Ball is an artist and currently Research Fellow at the British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection at Central St. Martins College of Art and Design, London. Information can be found at www.steven-ball.net and www.studycollection.org.uk.