Films and Performance Work by Stephen Niblock by Peter Chapman (1982)

The Funnel, March 12, 1982

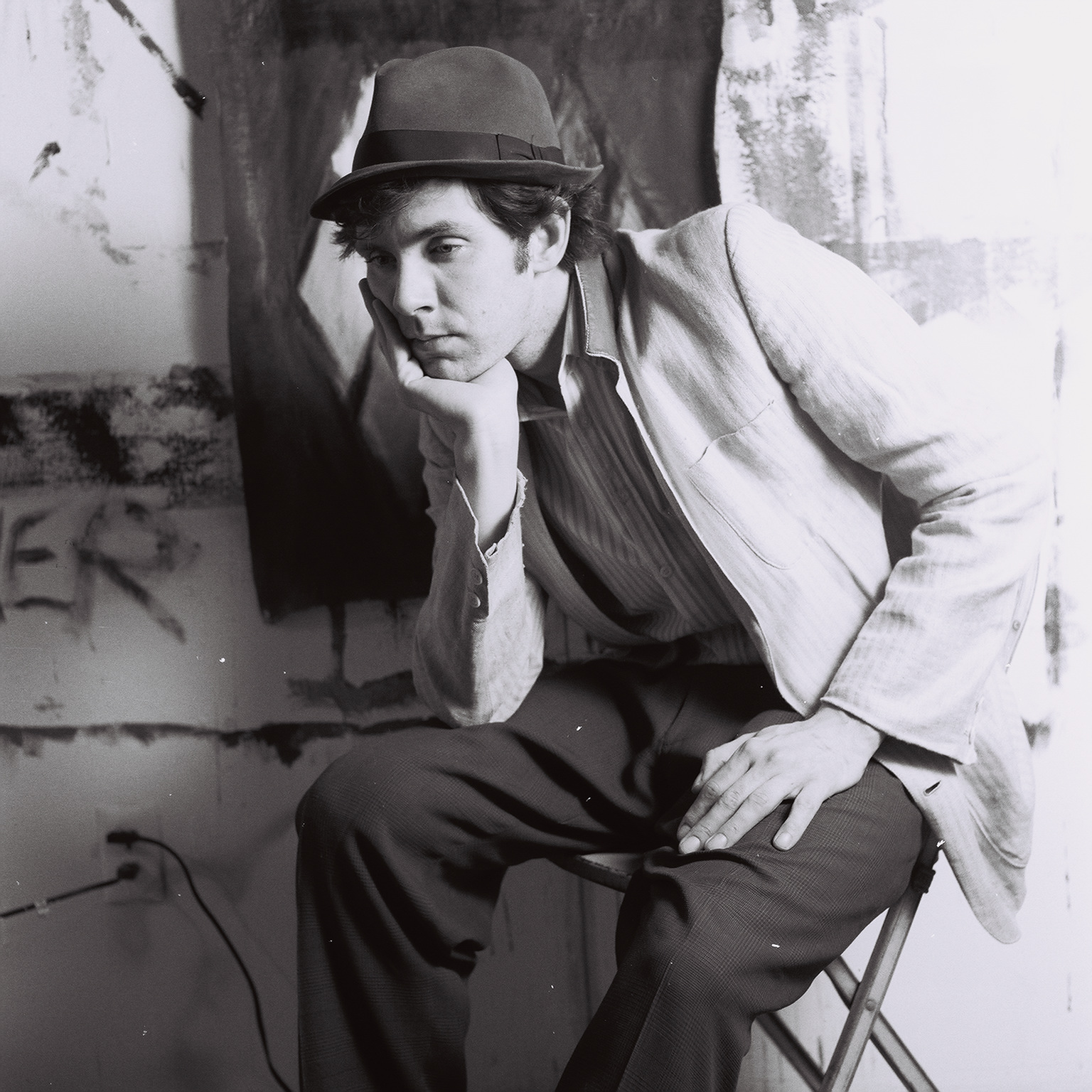

Stephen Niblocks’s show at the Funnel this March will be the first time that this long-standing Funnel member has ever screened all of his work-to-date for a Toronto audience. Along with his films, Niblock will also perform his film/performance piece The Magician Sees in the Funnel Gallery. He has covered a lot of ground over the past few years and, despite the breadth of material that will be screened, Stephen’s work in sculpture, installations and stage design will be absent. Some part of his three dimensional work, along with his own approach to film and poesy can be found in The Magician Sees. Having seen this piece during its initial run at the Theatre Centre’s Rhubarb Festival last November, I’ll try to outline it here as briefly as possible.

The Magician Sees begins dramatically enough; the darkness of the theatre space is illuminated by a film projector, the audience silenced by the sudden clap of two wooden blocks. The work presents us with a field not of standard theatrical conflict but rather one for contemplation. The final result being like an intriguing yet hard to recall dream or fable. The details blur with the viewer’s own associations.

The spatial centre of the action is a large, circular and rough surfaced screen against which a collage of images fall; a dissolving procession of shots buried inside a swirling and reticular colour field of paint and applique. Out of this, we see the chief visuals of the work; shots of a man’s heavily made-up eyes, a white bird, paintings of white birds and a young woman. These assert and reassert themselves within the film and in juxtaposition to the events played out around the screen.

A man, dressed in standard street wear (standard for King and Bay), blunders into the cone of the projection. He stares at the images before him; uncomprehending yet transfixed. He hurries out of the light. There is another loud clap. The man reappears, somersaulting back on stage in the garb of an Oriental fighter. He looks out into the audience and, in perfect synchrony, blinks his eyes in time with the theatrical, greasepainted visage which now dominates the screen behind him. Our hero then pulls out a flash camera and attempts to photograph his surroundings. Retreating to the side, the man observes a candle-lit ritual before confronting the projection again. Standing once more before the screen, the protagonist looks at the flowing images. Tentatively, he takes hold of the screen and begins to run in a circle; the screen pivots about its vertical axis. The images anamorphically flip-flop before us, their flatness exposed and now exploited by the running man/magician. Another dimly seen figure runs with the screen on the obverse side. The spinning stops.

Before us stands the young woman whom we saw on the screen. She releases a white bird into the space while the “magician” reappears, races across the stage and releases a cascade of cloth birds from their hiding place in the theatre’s rafters. The film ends. The piece is over.

To try to condense this any further would involve a judgment about meaning. Nothing is spoiled for any future viewer of the work by this description. Nibock’s filmed visuals and stage design are not that easily summarized. Besides which the version to be performed at the Funnel will probably differ from the above at certain points. On the other hand, to launch into some attempt to give a concrete meaning to this work would very quickly exhaust the surface area of this newsletter. Niblock’s images run from the banal to the mythic and resonate at many levels. One can get lost amid detail.

What I find intriguing about this piece and Stephen Niblock’s work as a whole is his faith and mastery of images. I find myself at the limit of my ability to say what I see at work here and yet I am delighted. There are times when I am not convinced that film is a visual medium. As absurd as that sounds such a thought follows as a logical consequence of a reductivist approach to art or merely pondering whether what one is watching on the screen is an image or an idea. Often what we see as film is mere accompaniment to a soundtrack. This commitment to the visual is more than just refreshing, it is engaging. Stephen’s vocabulary and his sense of rhythm are almost musical… Stupid like a painter? …Stupid like a fox.

Peter Chapman, Feburary 1982

Originally published in Funnel Newsletter Volume 3, Number 4, Winter/Spring 1982. Editor: Anna Gronau