Ellie Epp: Notes in Origin (an interview) (2000)

Ellie Epp is a Vancouver-based artist who has made four short gems in the past three decades. Largely silent and containing little camera movement, they celebrate an erotics of attention, taking as their subject a London swimming pool (Trapline), venetian blinds (Current), the Canadian wilderness (notes in origin), and film itself (Bright and Dark). Each of these films demonstrates the act of looking, carefully re-marking the line that separates the visible world from an off-screen eternity. Fascinated, languorous, and rigorous, they serve to reanimate the viewer, who is the real object of the camera’s gaze. It is from these moments of attention, collected over a lifetime, Epp argues, that the stuff of personality is made — incendiary moments burned into the synaptical roots. Each of us is a frame for experience, looking out through habits of seeing which she makes visible in her work, suspending perspectives of the everyday.

EE: My family are Mennonites. They farmed in Holland for generations before religious persecution drove them first to Germany and then to Siberia. During the war between the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks, their lands were confiscated because they were kulaks. That’s when my grandparents on both sides came to Canada with their many children. They settled in northern Alberta and homesteaded through the depression. My parents were married during the war. After the war both sets of grandparents moved to British Columbia, but my parents stayed behind because my father was attached to the land. I don’t like my father, I think he’s quite malicious. But there are times I’m grateful to him because he stayed and so we had the farm, and I loved the farm. It’s only recently I’ve realized how much of a shift my parents made. I thought of them as tied to an old culture, but they made important breaks very young. When they married he was twenty-one, she was nineteen. They insisted on being married in English, not the German they’d been raised in. That was unheard of in their congregation. As I grew up I was still hearing German preachers ranting about hell. Later, when I heard tapes of Hitler, I recognized the tone. Maniacal. My parents never left the church but they softened it for us kids. I got my first Canada Council grant when I was sixteen. They had a program that sent high school students across the country to see plays at Stratford. We would sit in our berths on the transcontinental train and talk, and some of the wiser heads told me about Huxley’s Brave New World. I read it when I got home and it de-converted me overnight from my family’s Christianity. I thought, “I know doublespeak.” That was an amazing thing for the Canada Council to do. It wasn’t the plays, it was finding other people like me.

After high school I went to Queen’s University because I wanted to go as far as I could from home. My parents hadn’t been to university. I’d no sense of where to go until I saw a pamphlet that had managed somehow to get to my little high school in Sexsmith, Alberta. There were pictures of the university’s ivy-covered buildings next to a lake. They said it was a small place. I won a scholarship and got onto a train in September 1963. My whole family came in the grain truck and stood on the platform eating ice cream cones. The train arrived and I got on with my portable typewriter and my blue suitcase and went three days and nights to Kingston. They had a program where you could have three majors so I did philosophy, psychology, and English. It was great. After two years I went to Europe and hitchhiked around for a year. Then came back and finished. In the dorm there were all these Toronto/Montreal kids, and for them it was all old hat, but I thought it was really interesting, though socially hard. I had a lot of cultural catching up to do. I thought I was going to be a child psychologist. I’d started working at a children’s centre called Sunnyside. What I discovered was that I didn’t want to socialize the kids; I liked them as they were, especially the wild ones. So I got fired and had to figure out a different career.

I was in the library and opened up a Sight and Sound magazine, a new publication at the time, and there was a full-page ad for the London Film School. I thought I might do that. Peter Harcourt came to Queen’s in my last year and taught courses on European and American film. He had just come from London and was full of the discovery that you could actually say what you thought. That was a radical discovery in those days. I couldn’t but he could. He’s the same way now but it was more unusual then. It wasn’t so much the courses but I liked Peter. We became friends and he liked my film writing. I thought I would be a documentary filmmaker because I’d seen work from the National Film Board that I liked. You remember Skating Rink? It was just a rink with people skating circles in some small town. There was no story or narration, just a film showing someone looking.

The year after I finished at Queen’s, I worked long enough to buy a still camera and began taking slides. There’s one taken in a crouch from behind a bush. I’m looking through a fence at a horse, and when I see it now, it’s like understanding you can make a picture of your present situation. In the sense of being hidden. The picture showed the person who was taking it, rather than what was in it. That was the discovery. I left for London with Peter. He was going to a conference. When he went home again I stayed. He knew about the Slade School of Art and urged me to apply. Their film program meant drinking tea with Thorold Dickinson, who’d made a couple of feature films in his day, so he was considered competent to teach. They took on four people a year who ate tea biscuits together, watched films, and once a week Thorold would tell stories about the old days in the English film industry. That was it. There was no filmmaking instruction at all.

MH: Did you see any experimental films while you were there?

EE: This was in the early seventies and the London Filmmakers Co-op had regular Wednesday night screenings. They had just moved to the Dairy, which was always cold, with old mattresses on the floor to sit on. Anabelle Nicholson was doing performances and Malcolm LeGrice was around, but it took a long while to get to know anyone. They would have these films that would go on a long, long time, and eventually I caught on to what one could be doing with this time. There was a lot of performance work and expanded cinema. If I wasn’t going to movies at school, I was seeing them downtown, six or eight films a week usually. I was living with a man who was friends with the anti-psychiatrists Laing and Cooper. That was a disaster. I had a child in December 1970. It was a really difficult time personally; the man I was living with was clobbering me and I had this little child to look after. There were no transition houses then. I had to find somewhere to live. I found a place and then daycare, which was the great salvation of the time. And then feminism was reinvented in London. It actually arrived from America. Time Out was a new magazine, with an entire section devoted to consciousness-raising groups; you’d find one in your area and go. I was very poor, on welfare. I didn’t have money for babysitting. Sometimes I would leave my child asleep and slip out to a meeting. I’d walk into a roomful of people who were basically friendly and interested in each other. It was a moment when something turned around, when a whole era turned around. I went every week, made friends and began a political life, marches and demonstrations. On Women’s Day we dressed as brides for a march to Trafalgar Square. I carried a sign that read “I won’t,” because in England the vows are not “I do” but “I will.” I was marching with my boy in a push chair and had a chain around the waist of this bride’s dress. All of a sudden there was a community and an understanding of politics, that it has to do with what takes place between any two people at any instant.

MH: Did it all seem like unrelated moments — the co-op, the women’s movement, the child?

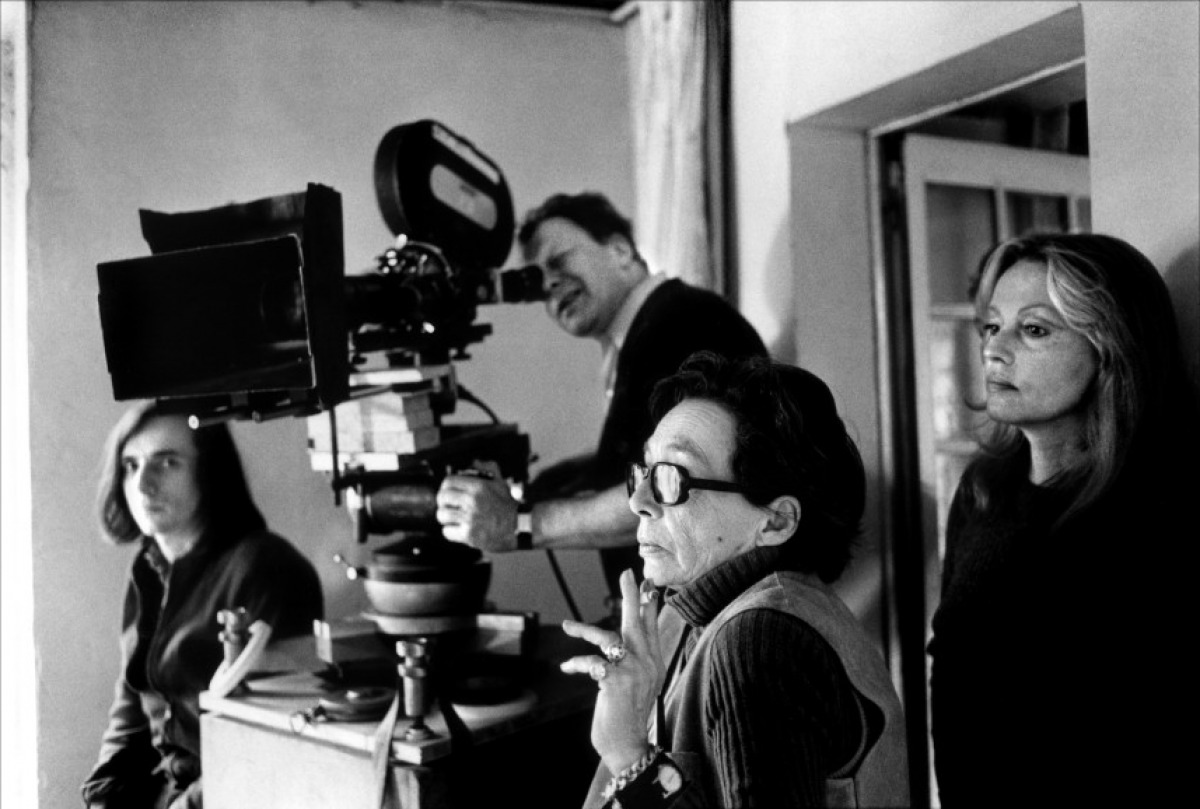

EE: I still didn’t know anyone at the co-op. It wasn’t an easy place to break into. But I hadn’t taken my first step. There wasn’t any way to be a part of that until I was a filmmaker. There are an awful lot of people in London. Why should anyone be interested unless you’d already demonstrated you were capable of doing something? In 1972 my child was two and began spending alternate weeks with his father, who was living in a commune. I knew the commune would look after him even if his father wouldn’t, so I had those weeks free. I found a kundalini yoga class which was very intense. They did very hard postures and held them for a long time. It really did something, I don’t know what. It gave me a little more gumption, a ferocity. Then we had the Experimental Film Conference and Rimmer was there and Joyce Wieland and Michael Snow. David was famous in London. He was so beautiful they put his face on the cover of Time Out. And he had those beautiful films. I saw Chantal Akerman’s Hotel Monterey and that was the one that lit the fuse. I saw what I wanted to do. It was the sense that you could use film to engineer a change in consciousness.

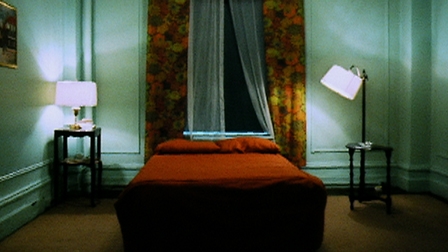

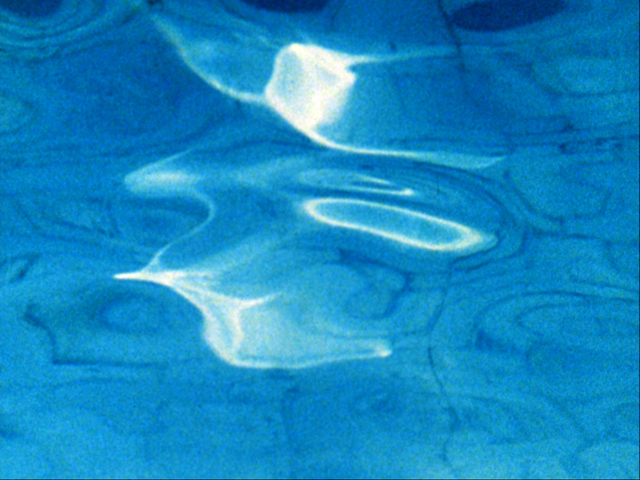

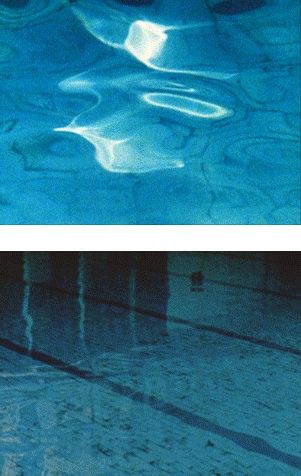

During the festival I stayed in Ladbroke Grove near Notting Hill Gate. I wanted to stay somewhere other than home because I needed to have an adventure. So I pretended I couldn’t stay at home. I went around telling lies for practice in those days; it was part of the exercise of liberation. I’d been so trained to tell the truth, I thought it would be interesting to find out if there was energy to be had in lying. And there was. It was quite a fantastic place I stayed in. There were a couple of sculptors living in a condemned house; most of the neighbourhood had cleared out except for some artists. On Silchester Road there was a swimming pool scheduled for demolition. It was attached to a Victorian laundry that had a huge room which housed washing machines of the time and nine-foot doors that sealed drying closets. I knew I was going to make a film there, my life depended on it. While I was at the Conference there was a feeling that unless I did something soon, I would never have any contact with anyone I wanted to know. First I had to figure out how to get hold of a 16mm camera and sound equipment. So I signed up for a course that Mike Dunford gave at an adult education institute. I did it out of pure calculation because I knew he had a camera. When I asked to use it he said half of it belonged to his girlfriend, Sally Potter, who I met and liked. She was a dancer then at the Place. I was terrified of breaking their Beaulieu and couldn’t always get it. The sun is very rare in London winters, and I needed both the camera and the sun on the weeks I didn’t have my child. There was a lot of tension waiting for these things to happen. My mother had given me some money for the film stock, and in order to get it processed, I worked as a domestic cleaner. Every two or three weeks, I’d get 100 feet of film and go stay in Ladbroke Grove with Tony Nesbitt, the sculptor. We were lovers at the time. That was the winter I shot Trapline. One of the things I see in it is what a good time I was having with Tony in bed. It was the first time in my life that I figured out what it was supposed to be like. I had signed up to do a PhD at the Slade but ran out of funding and dropped out. I was still trying to use the Slade’s Nagra but they caught on and James Leahy, the new boss in the film department, would scream at me. There was always a fight at every level for the equipment; the barrier was learning how to do it as a timid female person. But suddenly I knew the film community, Sally and Mike and Anabelle and others. To look at developed film I had to go to the Co-op. There was nobody who would teach me anything, or if there was I was too diffident to ask. Finally I found this eleven year-old boy who used to hang around the Co-op and he showed me how to use the editing equipment. That was in 1974. Then I took my footage to the Arts Council of Great Britain to get a completion grant. David Curtis was running the program. I just came off the street, he’d never heard of me, but they liked it and immediately gave me £400. I used it to come to Canada because I was frightened my child’s father was going to kidnap him and take him to South Africa. I had to get away, so I came to Vancouver.

MH: Did you know people there?

EE: I’d been to Vancouver as a child because my grandparents lived up the road in the Fraser Valley. I got a job to get the money to finish Trapline, which wasn’t cut yet. I didn’t have access to anything but then I got to know some of the students of Al Razutis, who was teaching at the Emily Carr College of Art. They snuck me into the cutting room at night and I would lock myself in and the guard would come and go, not knowing I was there. I’d come out in the daylight. I cut it with rewinds, a viewer, and a squawk box. It was quite terrifying because it was like cutting blind. I got it from the lab and showed it to Razutis’s class. Al said, “Well, it’s got soul.” The film represents a battle between structuralism and beauty because at the time there was a great mistrust of beauty. But what drew me to the swimming pool was the way it looked — it was like being inside a crystal. And the sound was like life before birth. But I didn’t know any of that then. It was made very intuitively. I knew you’d never see the whole space, that it would be developed through inference. I knew it needed a lot of black in it, spaces where you were only hearing the sound, to ensure you could really hear it. There was something I learned from Marguerite Duras’s Nathalie Granger. A group of women spend an afternoon in a house, and at the end of the film they look out a window and see a man, a stranger, walking on the street. He walks out of frame and the film stops. What I understood was that you could make the motions in the frame do what the film was doing. In Trapline (18 min 1976) the first image shows the surface of the pool and an ambiguous reflection. While the reflection appears right side up, it’s actually upside down. There’s a person at the far end of the pool who dabbles a foot in the water and this sets up a movement that comes down into the frame from the far end. It was like this image saying, “Here is the film starting to move. This is the rate of flow of the film.” All the pool’s spaces — the far wall, the water’s surface, the ceiling — appear on a single surface. The opening shot summarizes the space in two dimensions.

The last shot shows three kids sitting in the shower. There was something in that shot I didn’t see until years later, when it was projected on a really big screen. I’m convinced there’s a large participation of the unconscious in taking pictures. Many of my slides, for instance, were taken by the unconscious in the sense that there’s something right in the middle of them that I don’t see until years later. From the way something’s framed, it’s obvious that it saw it. And theoretically this is all possible. The eyes have connections through more than one centre into the brain. Blind sight. That’s a digression, but the last shot has these three kids in a warm shower, sitting and talking. You can’t see the water coming down, but you infer it. Next to them there’s a booth closed with a blue curtain, and something inside is jostling this curtain; it’s quite comical, and just before the film cuts out you see a pair of bathing trunks hitting the floor. Because someone is changing. The gesture inside the frame is the gesture outside the frame.

MH: Was Trapline the beginning of a public life for you?

EE: It was a very quiet acclaim. It’s done all right lately but for years it seemed surrounded by silence. Then a couple of years back I discovered it’s a classic. And how it ever got there I don’t know. It had no middle age at all. It wasn’t until ten years after it was finished that it started to get shown in schools. I think if I’d been turning out more it would have been different. If someone called from the newspaper and wanted to do an interview I would say no. I didn’t feel ready. I think that was the right decision. What was satisfying was that I had people to talk to, and that’s what I wanted in the first place. In Vancouver there were a lot of women artists doing multimedia work, a very intense community of writers and photographers. There were readings and Sunday afternoon salons with exquisite attention and devastating judgments of each other’s work and being. These small groups of people worked ferociously and competitively, driving each other on. You always have particular groups of people who are your points of tension, that you feel you’re up to in your work. What was wonderful about it was that you could bring in anything as far out as you could find to do, and there would be fine attention for it. It was also a drug scene and I was never very regular with drugs — I didn’t get to them at all until 1979. I remember someone gave me a block of hash as big as a cigarette package for my birthday, and I forgot it was there and threw it out. Even a little bit of drugs went a long way, and I had to spend years thinking about it, rebuilding and reshaping things. I know that sounds strange to people for whom it’s like coffee, but for me it was like a demon, a very powerful demon.

MH: Did you think of yourself as a writer, an artist, a filmmaker?

EE: I always felt my difference. I was rural and they were very urban. People who grow up with that kind of space around them have a different relation to everything, I think it goes quite deep. I was quite frightened of those people. They went out of their way to frighten me. Because I was frightenable. I was kind of a hick. I discovered gradually what kind of hicks they were, but it took a while. I was hick enough to be gullible, but it gave me a push.

MH: How was your work received?

EE: Ungenerously. I had to learn to hang onto my own sense of it. That was the exercise. I applied for a Canada Council grant to make a landscape film and sent them Trapline and they gave me $10,000. Many scrambled years later that turned out to be notes in origin. I bought a car, a 1962 Studebaker, and learned to drive. I was thirty-two. I drove up through the mountains, taking ten days to move eight hundred miles. I headed for the piece of land I’d been raised on in Alberta. It no longer belongs to my family; it’s owned by a lawyer who bought it for an investment. But I drove straight on up to what used to be the yard about two o’clock in the morning and went to sleep. Woke up in the morning and camped for a while. I just sat there and saw this amazing space; you could see weather systems passing hundreds of miles away, moving through the sky. Why had I come? I’d gone away and learned attention and now I was bringing that attention back to a place where I had all these physical connections. When we were little, the three of us kids walked a mile and a half to and from school, through whatever weather or colour changes were happening. I rewalked that path, stopping at the halfway bridge to look at my reflection. I was going round taking pictures of things I used to look at. Like the dirt road with the weeds coming in between the tracks, the rock piles and fence posts, the bush and cow paths. It was all interesting. It was bringing the London Film Co-op to La Glace, Alberta. Taking the attention that had come from those stoned artists in Vancouver to my family. It was fairly overwhelming. Sometimes I had to just sit still and remember to breathe. And in some of those painful times I would go out with my camera and there would be incredible things, like the slide where there’s a rock suspended in what looks like the sky. It’s really a reflection in water, but it looks like the sky. I asked some people if I could live in a granary in their field, and they said okay. I left when the combine started harvesting. I had my typewriter in the car and took to sleeping outside — I did that a lot in the next years. In the evening I saw the northern lights, this incredible curtain going across the sky, and when it got to be winter I found a farmhouse and rented it for seventy bucks a month. I didn’t want anyone to know where I was. I had a tape recorder and would read into it at night, learned the constellations, watching the changes. Then I had to go away and find work. There was a lot of oil activity in Alberta so I went to Edmonton and got jobs as a substitute camp attendant or a janitor and moved all over the province. Every job would last a week and I would stay in my room and drink coffee and it was so quiet, so interesting. In the years between 1978 and ’81 there was never enough money to stay in the country but it was getting harder to leave. After a while it was like being sunk in meditation ,the whole time. The physical place was so powerful, the most ordinary life of the land. I would come out the door in the morning and just be staggered. I felt it was paradise, that paradise was a matter of slowing your attention down so you could see it instead of talking to people in your head. Being more at large. In Vancouver I lacked continuity; I was really a different person and felt drawn back to Alberta to remember, to make the connection between the new person and the one I’d been before.

MH: Tell me about notes in origin (15 min silent 1987).

EE: The film that came out of that time was a pile of hundred-foot rolls. I really loved them that way, that’s how I wanted them to exist. They were their own shapes. But there was never any way to show them. notes in origin is a kind of compromise because I think the hundred-foot rolls are better.

MH: There’s a number that precedes each scene.

EE: I guess that’s a literary convention. It’s saying that these things are quite separate from each other.

MH: There’s a time-lapse shot of the moon.

EE: It took two and a half minutes for the moon to rise into the frame. Exactly one camera roll of film. It had its own speed.

MH: Why two images of the porch?

EE: The porch I could watch all day, I find it really erotic. It works from inference again; there’s a nettle but you never see it. You see its motion and the colour of its shadow — where does the green of its shadow come from? The first time it appears there’s more happening, the way the nettle moves is nice in itself. The second part shows little going on except that the sun goes behind a cloud and comes out again. I suppose it’s slight, but it feels very powerful, the way the exposure changes and the nettle’s shadow disappears and returns. And then the bars of the porch start strobing. Because you have these white bars going through your vision, something starts to happen in concert with this changing of the light and the quality of attention evoked. The bars grow quite intense; it’s as if they go into another dimension and your brain takes over from the film. It goes into another domain, which is what I wanted for the end of the film because it was true for the time.

MH: Why the long shots?

EE: Technically, duration is something quite particular — when you keep seeing something that doesn’t change very much you stabilize into it, you shift, you get sensitive, you cross a threshold, something happens. It’s useful for anyone to learn to do that. It’s an endless source of pleasure and knowledge. And yet it’s often what’s hardest for people who don’t know it as a convention. It’s the central sophistication of experimental filmmakers. We all had to learn it. We probably all remember what film we learned it from. I learned it from Hotel Monterey, which Babette Mangolte shot for Chantal Akerman. Almost an hour, extremely slow. I made the crossing. It was ecstatic. What it is, is this: deep attention is ecstatic in itself.

MH: Did it take a long time to collect the footage?

EE: A couple of years. I’d been so many years without anything to show for them, and there was no way to exhibit the individual rolls. It was during a bad time in Vancouver, a dead time. I just went to Cineworks [film co-operative] one day and asked Meg to have a look at it, because the only thing that made sense to me were these hundred-foot rolls. That was the end of my career, those rolls sitting there, and she said to just put them together. As notes. So that’s what I did. I’ve never really had a feeling of satisfaction about the form of that film like I did with Trapline. But maybe something of the hundred-foot rolls has come through in the end.

MH: Do you ever worry about the mainstream stealing your work, converting it into ad styles for instance?

EE: I’ve had the opposite worry, that no one would ever use my work, that I was too isolated in my intuition to be taken up at all. I have sometimes seen films, even commercials, I could see Trapline in, and I liked that. I’m quivering now. Is it fright? I don’t think there’s anything in my work that’s stealable. I would like commercial moviemakers to copy my work, because then there would be more people like me, I’d feel more at home. I don’t think I want to complain about financial marginality. I’ve always supposed I could make money if I chose to. It is an extraordinary privilege to have been able to choose. The margins have been livable — even the margins of the margins have been livable. I’ve been poor. I have sometimes actually starved. I’ve lost teeth. But I’ve had a lot of freedom. I’ve had time. I’ve been able to track things in myself. Every once in a while there’s been a little burst of money from a grant, or a trip somewhere to do a show. I haven’t been able to imagine being more famous. I don’t like being booked up. It spoils the day. I feel quite rich. I’m rich because I can go places I know no one has been able to go. I’m well stocked. I have my own life probably more than any woman in the whole history of my family. It is amazing to have been able to choose the margins. I’m not just marginal in work. I’m personally marginal. I can’t separate the two kinds of marginality. I might do marginal work because I’m used to the margins. My work might not be seen as marginal if I weren’t personally marginal. I’m marginal because I’m a woman, too. The boys of the community haven’t taken me in either. And I haven’t taken them in. I don’t have the social complexity to be able to schmooze. What I’d most want to talk about is the working process, but there isn’t much to say about it. Making films is stressful, handling machines is stressful. Making films is machine-based to a horrible extent. The machines are so ugly and the images are so beautiful. The projected film image is the most beautiful image there is — pure coloured light. The colours of reversal stocks like Ektachrome. Coloured light is just bliss. Projected light is like light in the sky.

MH: Framing seems important in your shooting.

EE: Composing an image is a strange knowledge, you have it or you don’t. I know I can compose. I think cinematographers are born, you see it in the image as a kind of authority. When you are setting up a shot it’s by feel. You feel the balance in the frame. It’s very precise. You can’t approximate it. I learned something odd about composition: I’ve always shot with my right eye. When I tried to shoot with my left eye I had no sense of composition at all. I had no feel. I don’t know what that means. I’ve always shot on reversal. It comes from shooting colour slides, which I liked for the discipline. A slide’s framing is absolute, you can’t fix it later. You only have one chance. People have said they can see in my work that I’m coming from still photography. I can see that, too, but I think the fixed frame is appropriate to the kind of film I make, that sense of someone standing and staring. The fixed frame says that I’ve given the stage to the thing I’m looking at, I’m letting it take me. It is a kind of erotic.

MH: Tell me about Current (2.5 min silent 1986).

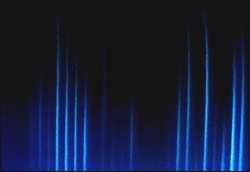

EE: It was made in the Anthropology Museum in Vancouver. It shows vertical venetian blinds which move because of the air conditioner beneath them. If you shoot through them to daylight on tungsten stock the light turns blue, so that became blue lines. It’s like looking at the northern lights to me, the stately way they move. And then the black spaces, the blinds themselves, begin to move the other way.

MH: It’s lovely. It’s like a pause, a meditation stop.

EE: I like it, too. I had it sitting around for years as a hundred-foot roll and then it occurred to me all I had to do was put a title on it. I shot it in 1977, but it wasn’t released until later.

MH: What happened after you were through living in farmhouses?

EE: I went back to Vancouver. Five hard years. A long time to be nowhere. My son was living in England and I didn’t have money to go see him and that was difficult. I was working very hard to learn to write but it never came together, never turned into anything. It was a time of complete isolation and misery and a long, slow breaking up with a woman lover. She was an Ezra Pound scholar, an exquisite writer, and I was there to learn something about writing. I endured this endless breakup on account of not being ready to leave what I was learning. I had another child. Which is, in a way, the last thing I wanted at forty. I was ill for nine months, miserable, malnourished, and broke. I hadn’t wanted anything to do with the child’s father. He was a smoker and the smell made me sick. So, this baby was born and his father turned out to be a marvellous parent. He said he wanted to look after his child, who turned out to be colicky, crying for hours every day. And he did. Rowen is now sixteen, living on Read Island with his dad. He’s okay. I say that with amazed gratitude that mistakes are not always final. Mistakes and irresponsibility. But I had to cast myself into the opposite of what I wanted for it to turn out well. From that point everything began to turn around again. It was very mysterious. Having to pay dues to life again. It was like saying you’ve been esoteric long enough, now you have to join up with human beings again and do your work in the community.

I went on and designed and supervised construction on a three-and-a-half-acre park on the downtown east side in Vancouver. It’s a community garden. We have worked with this land for sixteen years now. It is an established garden, a sort of people’s estate. There is a large formal herb garden, a heritage apple collection on espalier, a grassy orchard, a wild area with willows and species roses, two hundred allotment plots, a long vine walk with grapes and kiwis, and a kids’ area with a thirty-foot reflecting water tank made of reinforced concrete. Last summer we finished a house for our garden. It was built by young women who learned carpentry in the process of building it. Working with a community has been a revelation to me. Isolated art is not the only kind of life. It’s possible to have fun. I got this community life where I could be a general and a polemicist, a farmer, an architect, and a designer.

In 1989 I went back to school. I’ve been using connectionist neuroscience to try to build a way of talking about perception and representation that would support my actual working interests. The theory we have doesn’t at all. My films have been beyond me. They are my best work in any medium, and yet I have thought much more about writing and I’ve been much more noted for making gardens. In film I have been as if respected and suppressed. I’ve been easy to suppress. It’s as if the work most of the time is nothing. Then sometimes there’s a moment when I’m in awe of it. I’ve worked so simply that there might be nothing there. It is always that I want to show something I love or to show my love itself, but even for me I can never know it’s really there. At public screenings, I might feel it, or I might find the film unbearable and empty. It’s not robust work. And yet the sort of liking there has sometimes been for it is very satisfying, as it is an unfailing test both of people and of moments. I think my films are erotic. Or maybe my sense of erotic, which is that kind of complete attention, entranced attention, to nuances of contact and motion. My films, when I am able to see them, are total pleasure. They’re light-fucks. David Rimmer talks about the erotic quality of the film image and the way people often can’t stand it to be that, basically can’t stand to be fucked in so tender a way. It’s occurring to me that I was a child who often stood still watching other people move. I couldn’t skate. I’d be standing on the edge of a lake, filled up with the beauty of other people’s motion and the pain of not being able to do it myself. I took a strong imprint of those shapes of motion. I can unreel them at will. This is to say that maybe my films are marginal because people feel too much of the isolation in them. Its sting as well as its gifts.

Ellie Epp Filmography

Trapline 18 minutes 1976

Current 2.5 minutes silent 1986

notes in origin 15 minutes silent 1987

Bright and Dark 3 minutes silent 1996

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.