A Funnel For Talent by Anthony Hall

(Cinema Canada, February 1979)

Film has often been called the ultimate cooperative art form. But as film technology becomes cheaper and easier to operate, the necessity for collective effort declines. Increasingly, the individual can use the medium as a truly personal vehicle for artistic expression. In the late 60s there was a surge of interest in this new kind of alternative, highly individualistic cinema, but somehow no major outlets developed for it in English Canada. Groomed on the formula productions of institutional giants, film and TV audiences found it difficult to accommodate the raw directness of works left unrefined by the technical skills of highly trained teams of experts.

Finally there are signs that some of the obstacles are breaking down between movie viewers and the artists who want to make completely personal statements through film. The filmmakers compelled to take on all the technical problems of the cinema – from scripting to photography to sound to editing – are now concerned about marketing. Distributing, advertising and exhibiting are coming to be seen as integral parts of the whole art of filmmaking. The rapid development of The Funnel, Toronto’s new home for alternative cinema, is a powerful example of this process in action.

Primarily, The Funnel is a film gallery where works of alternative cinema are regularly shown and discussed, usually with the artist in attendance. Featured last year, its first year of operations, were the creations of Toronto’s rising generation of new wave filmmakers such as Keith Lock, Villem Teder, Bruce Elder, Anna Gronau and Frieder Hochheim. Also invited to show their work were a variety of artists from outside the region, like Byron Black of Vancouver, Taka Iimura of New York and James Benning of Oklahoma. Occasional evenings have been devoted to the offerings of particular institutions such as the Film Co-op of London, England. And once a month there are open screenings when anyone can bring in their films to be viewed.

Much of the material shown is on Super 8, the medium whose easy accessibility best corresponds to The Funnel’s democratic philosophy of film. The view of the art is well articulated by 24-year-old Ross McLaren, The Funnel’s founder and principal dynamo. “Anybody can do a film,” he insists. “The technical end can be learned in half an hour.” To McLaren, the layers of mystique surrounding the cinema have prevented individuals of modest means from realizing the form’s full potential. “There is a belief that to make changes it takes thousands of dollars and the expert knowledge of a great many people,” he maintains, continuing: “The result of this kind of thinking is that the media is monopolized by glossy films that are realer than real. Their production is modeled after a Detroit assembly line with particular craftsmen responsible for every stage of the fragmented manufacturing process. Like this the original concept gets watered down, and it is the concept, not the technical thing, that is the most important part of the film.”

McLaren in his own work, like most of the filmmakers showing at The Funnel, aims to move beyond the structural bounds confining commercial movies with their traditional emphasis on narrative. “Reduce film to light and emulsion and acetate,” says McLaren, “and start from there. Don’t even think of telling a story.” Accordingly, much of his varied output, such as the widely acclaimed I.E. and Weather Building, might be termed “experimental.” But associated even with this catch-all film category are a growing number of conventions, all of which McLaren seeks to escape. With his most recent production, Summer Camp, he evades practically all labels.

This 16mm black and white “feature,” notes McLaren proudly, was made for $400 – a budget much higher than most works shown at The Funnel. The film pokes fun at the CBC’s professional pretensions and their unimaginative way of adapting theatre for television. The movie is a straight assemblage of nine intriguing screen tests made by the Corporation in 1964. McLaren simply took hold of the footage as it was about to be thrown away and ran off a print adding only his own name on a credit. In laying claim to a piece of cinema in this fashion, McLaren calls into question certain assumptions concerning the nature of personal creativity. He provokes consideration of the limitations of an artistic form, much as Andy Warhol did when he placed a frame around a Campbell’s soup tin, or as Michael Snow did with his 45 minute zoom shot in Wavelength.

Many of McLaren’s other cinematic efforts, in spite of his disparaging comments about commercial filmmakers’ preoccupation with craftsmanship rather than concept, display an impressive degree of technical wizardry. They travel widely in the United States and Europe and have won their share of awards. But McLaren sees these victory garlands basically as hollow stamps of approval. “There are today so many festivals,” he explains, “that virtually every film done can win some sort of prize somewhere.” What McLaren seeks most from his work is the opportunity to talk about it with small groups of people and The Funnel was established to provide an environment where filmmakers can get this feedback – a crucial component of the creative process. Says McLaren, “Films are not only screened here but they grow out of The Funnel… The fact that a place like this exists is a good incentive to go out and shoot films because of the certainty that there’ll be a place to show them.”

Of course The Funnel is not the only place in Toronto where works of alternative cinema are exhibited. At the Art Gallery of Ontario, for instance, experimental films are often screened under the auspices of Ian Birnie’s Media Program. “but before works receive such prestigious, institutional recognition,” notes McLaren, “they have usually been around for awhile. What The Funnel does,” he continues, “is to provide a testing ground where people can show their films for the first time… where they can get a start.”

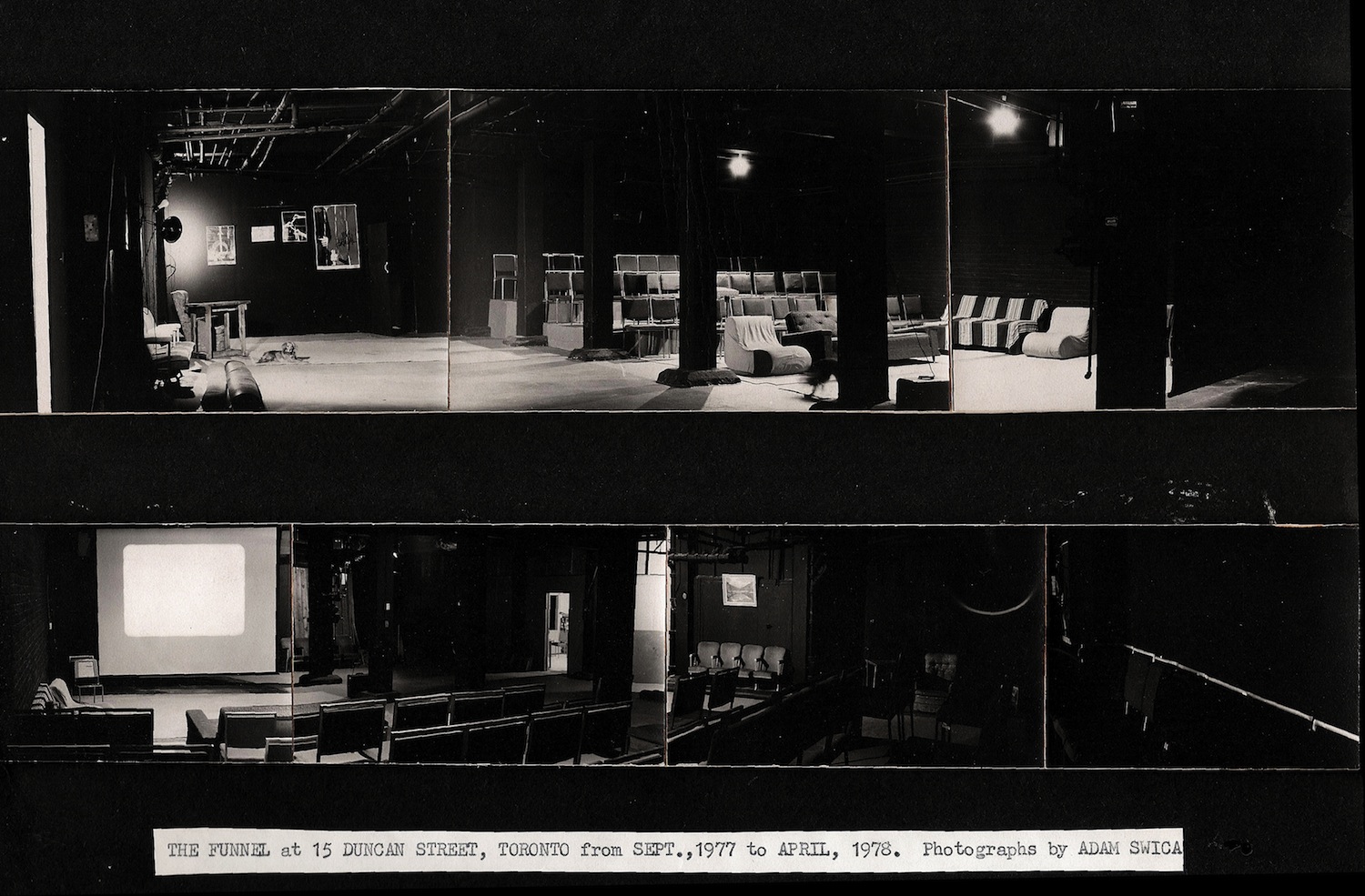

McLaren had no such outlet for his work when he began making films as a student at the Ontario College of Art. His resulting frustration prompted him and several friends to found the Toronto Super 8 Festival in 1976. But the initiators were soon muscled out by more commercially-minded interest who have since made the event, says McLaren somewhat bitterly, “little more than a trade show.” The Funnel was McLaren’s next venture into film exhibiting. This he originally established in a Duncan Street basement provided free by the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication. The partnership between CEAC and The Funnel proved short-lived, however, once the latter failed to back up the former’s publically proclaimed support for the Red Brigades. Accordingly, McLaren and the dedicated group around him have a new address at 507 King Street East, where renovations madly took place in anticipation of this year’s opening on December the eighth.

With the same low budget mentality they apply to their films, all the work on the new space is being done voluntarily by Funnel members. Many of them have offered their efforts repeatedly in the continuing saga to develop an environment in Canada where truly independent filmmaking can thrive. During the death throes of the Toronto Filmmakers Co-operative, for instance, six of the nine executive members who attempted to save the debt-ridden organization were committed Funnel associates. In spite of this similarity in personnel, however, it is asserted that The Funnel is not simply a replacement Co-op. “The latter was production oriented while the former is exhibition oriented,” explains The Funnel’s vice-president Tom Urquhart.

But while the two organizations have developed in different directions, Urquhart indicates that they both were started to meet comparable needs. On this he has a rare perspective, for Urquhart began working at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre (CFMDC) in 1971 when it was located in Rochdale College across the hall from Cinema Canada and the fledgling Co-op. “During those times,” he reminisces, “the Co-op was created by and for makers of alternative cinema. Since then it developed into a cooperative for people wanting a stepping stone in to the mainstream of the industry.” That The Funnel’s growth represents, in part, a return to basic principles by a section of the Toronto film community is further underlined by the fact that one of its greatest supporters, Jerry McNabb, was the Co-op’s first co-ordinator. Today he heads up the CFMDC, the nation’s major repository for experimental films made by independents. On McNabb’s advice, this organization has agreed to pay the producer’s rental fee on any of its works that are shown at The Funnel. In addition, McNabb has recently hired McLaren.

Besides what it gets from the CFMDC, The Funnel receives some funds from the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council. With the unfortunate history of the now defunct Co-op firmly in everyone’s mind, however, there is an unwillingness to become too dependent on the government. Thus most of the money comes from the members themselves who seem willing to pay a substantial amount to be part of an exciting new enterprise. Perhaps one reason for this is that at least half the budget is recycled, largely among the membership, in the form of film rentals. McLaren and his colleagues are fast learning how to temper their altruism with a healthy dose of business savvy.

How The Funnel might develop in the future depends only on the energy and vision of the growing membership. There is talk of a publication, the creation of an archival resource, and the renewal of the workshop program that McLaren started last year. But almost certainly the emphasis will remain on exhibition, with stepped up efforts being made to widen The Funnel’s circle of contacts. Says Urquhart: “We want to bring the alternative cinema from international origins to the Canadian audience… and also encourage the showing of Canadian alternative cinema outside the country as well as across the country.” In Canada, The Funnel is at present most closely associated with PUMPS in Vancouver, the Atlantic Filmmaker’s Co-op in Halifax and the Newfoundland Independent Film Co-op in St. John’s. Anthology, Film Forum, and Millennium in New York. All share similar goals, as do a variety of organizations in Europe with which Funnel members will be exchanging prints. Anna Gronau, a committed devotee of alternative cinema, sees this kind of long-distance interchange of films as a particularly humanizing aspect of the so-called mass media. Says she: “It encourages the creation of small communities around the globe where people meet to watch the same image, but are left free to react in their own peculiar fashion.”

Gronau’s respect for the individual movie viewer’s integrity is paralleled by the concern at The Funnel that film should be used to show and develop the artistic uniqueness of particular personalities. In order to create an intimate, human environment where this can take place, McLaren and his colleagues have joined hands in cooperative effort. While the fruit of their work may well become an important influence on Canadian cinema, it will probably never attract the attention of a mass audience – indeed, the very concept of mass appeal runs counter to the Funnel’s vision.