Engravings by Jean Perret and MH

In order for him to begin, to make a picture, Frank Cole first needs to invent the cinema in a gesture of absolute radicality. He invents true histories that are his alone to see, rooted in a terrifying refusal, and from which he can at last conjure himself with the aid of his camera double.

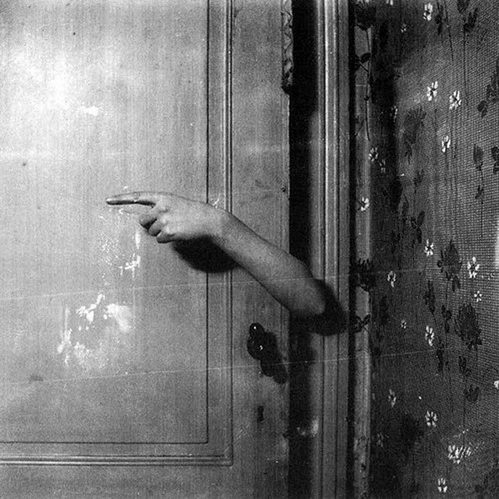

In his first two short films, he uses his voice to call from the other side of the abyss of representation, asking his subjects to join him in the necessary trial of reproduction. In A Documentary (1979), he approaches his grandfather with his voice, in a gesture that allows him to enter a primal scene of trauma, to look at exactly what he can’t bear to look at. Standing in front of the last forbidden door, he asks a question that permits entry. Once inside, he invites an epitaph from his grandfather. Every speaking is always the last word, every line might be chiselled into graveyard stone. His voice is also audible in The Mountenays (1981), where his beautifully simple questions are put to a family busy becoming pictures, and who are called to accompany this task by Frank’s voice. He meets them in order to create a portrait, a moving family photo, which is composed little by little when the last personages and even their dogs enter into the field of looking and take their pose.

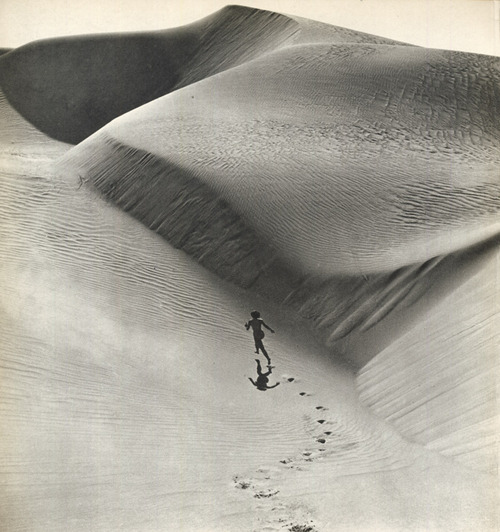

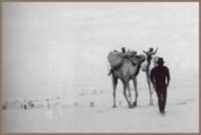

Frank’s body, which appears again and again in his movies, is also a way of looking. He moves alongside his grandfather who accomplishes the daily ritual of visiting his wife. Frank is a tender witness available in the time of their common life, which he follows until it is exhausted in a final, noiseless reckoning. He finds his own death there, in the death of his grandfather, and then undertakes a journey of spectacular risks to exorcize his death feelings. His progression in the desert accompanies the ghost of his grandfather. Here the film director works in a space that refuses the separation between the life of a movie and life itself. Each step is part of an approach to find the necessary distance between his subject and himself. He walks in order to put himself into position, again and again, in order to pose the question of seeing. At the edge of exhaustion, when he can hardly go on, the old habits are also fatigued and he can begin to see for himself. This idiosyncratic gesture bears us toward a place of mourning, where the dead are waiting for us. For Frank Cole the way is heavy and serious; here even colours shade into accents of black and white. The work engraves in a twilight aesthetic born of patience and silence. Beauty fades into darkness, arriving only at dusk.

These films are a song of asceticism that draw the field of his solitude and independence. Frank Cole carries his work to the very end of his energies, until he reaches the violent death that is inflicted on him. His immense, monstrous and fussy desire follows each careful step after step, granting death time to work.

It is hardly possible to heal the loss of the social body, but films can help us understand what we’ve lost and the interconnections between us. The cinema offers us a trace of what was once, a glimpse of the ghosts we are becoming, and the ghosts of those who are no longer able. Refocussed through the director’s singular quality of looking, we might again recognize the links of affection that lie between us, the melancholy that some are born into and the marks that lie inside the body waiting to be summoned by a picture’s impression.

Beauty is crepuscular. It obtains a collected silence in which one might discern the strained motivations between life and death. The best directors appear and disappear all at once, in the fragile ontology of their pictures. No sooner do they arrive, than disappearance begins. They offer us lyric epiphanies in the authentic voice of silence. Frank Cole disappears progressively in the depth of field of the film narrative that is presented. He grows fainter in the limitless desert, even as he allows us to hear the peculiar silence left to the survivors. In these distant, strained echoes we may perceive the memory of a lost harmony.

Nothing To Do With You

I knew Frank Cole from his desert movies, the long dry solo encounters, the broken flesh and stark beauty, but there are two black-and-white shorts, dating back to his days at Algonquin College, that laid the basis for all that Saharan heat. Like so much of the Canadian fringe, both are family pictures, home movies. The first he named A Documentary (9 minutes, 1979) and it pictures with a stunned precision the decline of his grandparents in an old age-home. There is a grief in these pictures so hot it burns to the touch, but it shows itself in the slightly-too-far-away framings that turn his beloved grandparents, and particularly his grandfather, into an element of architecture. The failing flesh, the knotted hands and spotted limbs — this is where Frank learned how to create a frame. The borders that secure each picture are designed to exclude first of all, ensuring that only the strong survive. And once he has cut a rectangle out of his own blood, he steps inside so he will be forced to look only at what he can’t bear, only at what he is required, as a duty, to turn away from. This would become the template for all his work.

Every frame in A Documentary opens the wound of his stare like a surgeon, deliberately and meticulously. At last, we make a terrible walk down the last hallway on earth to a room where his Grandmother lies in bed, moments away from death, and we are made to watch as Grandfather holds this almost-human in his arms. The camera is set behind the bed stand, looking at them the way an interior decorator would size up wallpaper or rug patterns. Unbearable. Grandfather’s face looks back into Frank’s face, and all of the anonymous watchers he has gathered inside his camera, and he doesn’t have to ask why. How can the end be so long? Death lurks on both sides of the screen.

This moment became Frank’s home, which he dutifully carried on his back in two long movies made in the desert. But before that he collected his second student short, every bit as powerful as his first, but composed in a different tone altogether. It is called The Mountenays (22 minutes, 1980) and initially appears as a kind of anomaly in his oeuvre. It’s as if Frank hoped to counter the spell of his dead grandparents by reconvening a family of endless vitality and invention, determined that every frame would erupt with an undeniable life.

And he can’t wait to get started. He offers us no preparatory moments or establishing shots, never mind the slow introductions of another life — all this has been left behind. Instead a young man appears in a skeleton of a forest carrying a bucket — winter coated and bare-headed and already on the move. One after another, he empties the recycled containers hanging from trees into his bucket, carrying the load of their sweet maple syrup, before walking over to the next trunk. But there is something in the way he performs his chore that doesn’t make it look like work at all. He doesn’t have the efficient walk of an adult accustomed to figuring, at every moment and without end, the shortest distance between two points. Geometry has never occurred to these feet, they are built for wandering, digression and play. The bucket tilts sideways and he looks unconcerned. If some syrup spills (though none of it does) that’s okay, there is always more where that came from. What a world of abundance; even the trees are filled with sweetness.

A pair of cars slide across a snowy road while shouts of glee rush from the driver’s seat. Happy to be in movement, there’s no destination needed — they find again in speed a forgotten tenderness.

In the next scene one of the two cars is parked by a morass of broken auto parts. The hood is open and Frank asks, “What are you doing now?” (The director, always off-screen, never hesitates to become part of the scene. He understands there is no way to be neutral and underlines his complicity with rehearsed, straight-man banter.) With the engine running, the young man explains that he wants to replace the engine he has with a bigger one. But when he reaches into the guts of the machine, he receives a shock and jumps away, a moment that is played for laughs (the truth is, he likes the camera and the attentions of this earnest young director).

Four brothers are also working on cars in what appears to be a wasteland of car ruins. Heaps of tires and body parts and abandoned vehicles are scattered in a forest setting as the brothers aim for more speed. A truck engine guns and pops, and each time it does, one of the brothers jolts as if he were part of the same nervous system. Part junkyard car, part country-life boy. Is that thing going to explode? The boys back off discreetly and leave their comrade firing up the engine, still in search of the perfect ride.

They look like children with their floor-of-a-world strewn with toys. Though everything is oversized, including the children themselves, who appear suspiciously like adults. And instead of toy-store miniatures, remnants of real cars lie broken and discarded at every turn. Wearing a checkered worker’s shirt and torn jeans, Ralph throws down metal slabs and tires. “What are you doing, Ralph?” Frank deadpans. “Cleaning the place up,” says Ralph in an unintentionally comic reply. He might as well be standing in the ocean announcing his intention to empty it a glass at a time.

Smaller children play in the car graveyard, and then we are led inside a single-room dwelling, home to all twenty-five of the Mountenay family. Every scene inside necessarily belongs to groupings and congregation. Dinner preparations are underway, and then they sit down to eat. Somehow, there are always enough family present to defeat the intrusion of the camera. It is still there and artificial lights augment the shine coming through the windows, but there are so many busy hands that life refuses to freeze up and wait for the camera to leave so they can be a family again. The animals are there, too, lending their grace and unconcern, a menagerie of dogs and cats hopeful for an extra spoonful, which always comes.

What a tangle of conversations all at the same time. And the camera right alongside.

They wrestle and smoke and comb their hair, stopping every now and then to cast big smiles over to brother or sister. When I see these young, doughy faces stretched into joy, I can’t help wanting that too. I want to lean into the picture and take these smiles and cover my face with them, knowing at the same time that they are part of a familial code, a bloodline and inheritance and daily living I will never understand, not even if Frank’s movie ran a thousand days long. The happiness each expresses creates a light in their faces, and it is with this light that they illuminate each other, and create their family. Perhaps this is putting it too simply. Perhaps I also have to add poet Anne Carson’s observation that every wound gives off its own light. Whenever these faces decompose themselves, whenever they are relieved of the mask of personality and the duties of presentation, whenever they give themselves over to the small revolution of a smile, they are also showing a wound. Every smile opens the face, and this opening is also a cut, a separation, a hole. Which doesn’t make me want them any less. On the contrary.

Mother is a large, dominating figure (she is the horizon, the beginning and the end), seen only in glimpses, orchestrating the background. Her long voice-over rap describes a visit from Social Services, who tried to take her children away. Strangers arrived one day from “Toronto,” a word she pronounces the way one would name a distant asteroid. “I said, ‘As long as my kids have got food in that house and a roof over their heads and they’re warm, they’re nothing to do with you.’ And we’ve plugged along ever since.”

The man-boy in the silver jacket laughs and walks through the chicken coop in a choreographed moment. “How many chickens do you have, Ralph?” Ralph makes Frank repeat the question, though he’s heard it perfectly well. While Frank asks again, Ralph preps his reply. “Ten,” he barks, looking into the camera with an accusing stare. Why is he so mad? He kicks a chicken. “How many geese?” asks Frank, still sounding like an astronaut. “Two geese and two ducks,” answers Ralph straight-up. Then he quacks like a duck with a mimicry so perfect I have to scan back and forth over the scene to make sure the sound is really coming from him. He smiles; the bad moment has passed, the accounting is over. “Can you show us the rabbit?” Frank asks him, and Ralph walks right over to the rabbit hutch. But when we see him again he’s wearing a different coat, on another day. The animals move in every direction. Ralph pets a pig. This is how quickly one day becomes another. Ralph is a little soft on the figures — maybe he never picked up the habit of counting — but he knows where that pig likes to be touched alright. And even though the silver running through the camera is too precious to be rolling hour after hour, and it’s clear there is something choreographed, nearly rehearsed, in these moments, the man-boy Ralph is still in his animal body; the camera doesn’t make him any bigger or smaller than he really is. He’s busy living dreams no one reckoned the words for and then it’s time to scratch the pig. Two ducks, and ten chickens and no one asked how many rabbits. They don’t write scripts like this because what is on display, what is at issue here, can’t be written down.

A blond Mountenay boy explains why he prefers to live out here: no rent, no cops. And you can drive without your lights on. This conversation, these lives, seem to be conjured out of a forgotten world beyond the flow of capital (there is no one busy buying or being sold). No one from outside is inside —the Mountenays live in a borrowed forest, only too happy to be abandoned and left behind.

Every look and word and gesture tells me again: this has nothing to do with you. Nothing.

At night they play cards and roll cigarettes and sing an off-kilter version of “Love Me Tender.” And then a slow, strummed singsong where all the kids chime in. The ones who don’t know the words hum along and that’s just fine too. You want a little music, you pick up the guitar and learn some, or croon along with sisters and brothers. No sales agents, no deals or downloads. Someone adjusts a light bulb and the screen goes dark.

In a single shot lasting nearly two minutes, the family slowly gather outside for a group portrait. They exhort off-screen members to join them as they stand shuffling and joking. But wait: those young children held in large wintered arms. Are they the result of sisters and brothers? Or fathers with daughters, mother demanding sons? Where have all these children come from? Am I seeing their darkness, or my own?

The credits appear superimposed on a striking image: one of the Mountenay boys is turning a large screw into the ice, moving his body in a slow, winding circle. How beautiful and futile this appears, and us alongside him, our hopes and strivings to make our own special hole so that we can frame infinity with the sum of our fears. His brothers join in, one at a time, and then someone lowers a pole and begins to fish. It is still snowing, but the fisherman has no gloves, he’s used to the outside. He’s lived out here all his life. He catches a large bass and then another. They call out to Frank, naming him “Frankie.” Close, they’re getting closer all the time.

Frankie’s out there waiting in the cold, too, he doesn’t mind. Beneath the ice, the fish are invisible. Beneath their poverty, their backwoods dress and expressions, this family is also invisible. But Frank never sees this. He doesn’t know how to turn them into characters and story arcs. It just never occurs to him. Instead, his own loneliness accompanies them and allows him, again and again, to find the right distance when setting up his camera. Not too close, not too far. Here is the magic of this short, beautiful film: if anyone else arrived, they would turn their cameras on, and the family would vanish. Even the animals would be missing. The forest would be empty, the shack house abandoned. Frank’s arrival makes their arrival possible.

But this conjuring feat is exhausting, and in his two ensuing features Frank would dedicate himself instead to the art of disappearance. He would use his camera to make everything around him invisible. How well he succeeded, this stern magician and home-movie artist.

Throughout The Mountenays he hovers at the threshold of the frame, calling out, asking questions. He wants to know what it’s like “in there,” in the abyss of representation. Soon he would find an answer to his question by stepping into the arena himself, his own best subject. His next two films largely focused on images of himself, though as anyone who has watched them can attest, he is not there. The Mountenays taught him how to disappear, and he would soon leave for the Sahara, where he could work this magic on himself.

In the Theatre

Up against another human being one’s own procedures take on definition. — Anne Carson

We never met. Though I heard his name spoken often, by friends and strangers, and always with a slight lowering of the voice, as if they were about to reveal a secret, inviting the listener to lean in close. “Frank Cole…” they would tell me, and then pause, letting the effect of the words sink in. It wasn’t like other names somehow, certainly not like the names of my peers, who were babies, children in the nursery of cinema, bewildered by the need to express longings which for some would never be named at all, even all these years later. But with Frank Cole — no one ever called him Frank, that would be altogether too casual, too offhanded for a young man born serious — the name was already something to aspire to. He had understood before any of us that the only way to make the stories cinema required was to live them first, and his terrifying commitment was enough to lower the tone whenever his name was dropped into the room.

Fall in Toronto means the Toronto International Film Festival, which used to be called, in a moment of breast-beating that seems somehow very un-Canadian, the Festival of Festivals. The long summer is over, and now it’s time to reap the harvest, the new crop of pictures gathered from round the world and laid up where we might be able to judge the distance between last year’s viewer and the present, trying to hip ourselves to some brave new trick of the light that would make our unaccustomed lives possible again. What we were watching, of course, was ourselves.

And this being a festival in Toronto, there was a requisite Canadian component, tucked away behind more glamorous emulsions. Here were eyes raised in our own light, and if these looks were not the usual, it was only because we’d grown accustomed, like most everyone else in the world, to the multinational musings that continued to occupy our cinemas and imaginations like an invading army. The cinema of Hollywood. But for a breathless stretch in autumn, it was possible to glimpse something else, and it was in search of this strangely familiar that I stood in queue for a new movie by the man whose name I’d heard only in whispers, returned at last to the place of his birth, but not before circumnavigating some lost continent, swallowing miles of the Sahara, beating himself with it, until the two had become, man and desert, inseparable.

The movie was called A Life and there are vivid stretches that have lingered long after a thousand other movies have paled. He couldn’t stop going, that’s what his friends told me. He travelled by jeep, and then went back to do it again on a camel, and then again by foot, crossing the Sahara of his life over and over, waiting for everything to change, and then everything did.

The film I saw was just a few minutes long, though A Life by Frank Cole, the movie that showed that afternoon at the festival, was, by anyone else’s account, a feature-length endeavour. There were just two scenes in my version of the film: one showed Frank walking the Sahara, while the other offered an unbearable recount of his grandfather’s last moments. His home-movie science fictions appeared in black-and-white, clipped from a re-view of Frank’s first film, A Documentary (1979). He returned to this footage like an obsessive worrying the beads, and what he found was not only his beloved grandfather, but death itself. Every black-and-white moment teemed with Swiss shock and outrage. The camera did not observe, it stared. The framings were coolly exact, the white-on-white institutional hallways and waiting rooms provided some further remove so the infernal miracle could take place. As the camera rolled, the man Frank Cole once knew, the grandfather of his youth, disappeared, and in his place stood death itself. This is the guide Frank used to make his way across the desert, which was not a memory, but a living hand showing him where to cross and pitch his tent and place his camera.

The film lasted just a few minutes and then the lights came up and for a moment there was nothing, not even the polite applause that greeted even the most execrable of the festival’s offerings (this was Canada after all), and then the programmer, it must have been Geoff Pevere, stood up and announced, “Frank Cole.” We were roused from our stupor and began to clap and the clapping lasted a long time, as if we were handing up not for this devastating film, but for ourselves, urging ourselves out of suspension. Then, just as suddenly, realizing what we were doing, in a collective moment of self-consciousness, the applause stopped. There followed nothing but a long and awful silence as Cole stepped away from the tribe, from us, as alone as he would ever be, leaving everyone a little shocked. Because the Cole that we had just watched crossing the Sahara was a lean, browned slip of a man, while standing before us was a great, eerie, bulked-up beast. Frank had obviously been doing some serious time in the gym. His neck, for instance, was now as big as my head, and his arms bulged out of the sleeveless T-shirt he wore for the occasion.

With an entirely affectless sense of drama, he stepped forward until he was standing directly beneath one of the harsh, overhanging floods of the auditorium which turned his face into a Halloween version of itself. Long shadows dripped across the place his face should have been and he smiled in a silence that absorbed everything it touched because after this movie we knew only that whatever the cause of his happiness it was nothing like a happiness we could know. He stood there with those twin beef pillows crossed in front of him, not saying a word, and no one else said a word either. Someone had told me — Lori maybe, or Peter, or Steve, someone who knew him when he was only human — that this movie was going to be called Death’s Death, but at the very last moment, as the program book was about to shipped to the printer, he’d decided to rename his film A Life. I stammered out this question hoping only to hear him break the soundless barrier, and after some lengthy moments of deliberation he said that while finishing the film he realized that dying was a choice. No one had to die. Because the words came out in a flat, even clip, there was never warning his speech was coming to an end, no dramaturgy attached to the rising and lowering of tones that offer cues to the listener. This was a democracy of language, each word granted the same weight and intonation, issued by someone who was mistrustful of speech. He had come to stand before his images, before the light that made his pictures possible, and as a result each of his replies (which were invariably brief) was followed by a long, nearly unbearable silence. This silence was more telling than anything he said, because this was the place Frank Cole must have wrestled his pictures out of. Later, when the last painful question had been asked, everyone made an uncommon rush for the back door as he stood rooted in the footlights. Unmoving, he watched us return to our ordinary catastrophes and begin the long road of forgetting everything we’d just seen. By the time he finished his next film, there would be no invitation to present it at the festival. It was already too late for that. He was found murdered, ambushed by thieves on his latest trek across the Sahara.

It was with sadness, and little surprise, that I learned of his end while flipping through the entertainment pages of Canada’s national newspaper. In the days to come, there were conversations with those who had surfed the same coast or sold him a camel. And there were others who had rubbed closer to the bone, those who might have sat and crouched in the same fire. They all said the same thing, the ones who knew him best, and the ones who didn’t know him at all. Frank Cole was dead.

Frank Cole films

A Documentary

8 minutes, black and white, 16mm, 1979

When Francois Truffault remarked that every director is condemned to remake their first film again and again, he might have been naming the project of Frank Cole. In Frank’s first short film, made at Algonquin College, he brings a terrifying mixture of intimacy and distance to bear on his aging grandparents. The camera is both stunned observer and an instrument of relentless pressure, urging its subject to go on, to show what cannot be seen.

Each frame is memorial, each shot might last forever. Each small moment of shoe-tying and hallway-walking is a necessary prelude to the film’s closing moment, where Frank’s grandmother lies in bed, hardly human, as close to death as one could be without giving in. Beside her is her lifelong partner, himself grown so very old, helplessly resigned to counting the remaining hours. In reaction to their failing flesh, the camera takes on the rigid architectural framings of the hospital, refusing any easy warmth and closeness, but maintaining always the terrible repression of distance, the merciless measurement required to look, and it is this calculus of pain that Frank revisits in movie after movie.

The camera squeezes the two grandparents; it pushes and pulls until it is clear that what we are watching is at once a couple at the end of their days, and death itself. It is as if, through the lens of his new medium, Cole is able to see his beloved grandparents for the first time, but the cost of his new found seeing must be paid by his subject. The ones he loved beyond death.

The Mountenays

22 minutes, black and white, 16mm, 1981

Frank’s second movie was also made at Algonquin College. It is a short black-and-white marvel of direct cinema. Here he visits the Mountenay family who live in a stretch of abandoned forest, next to an auto junkyard in the Ottawa Valley. The brothers appear first in a nearly endless succession, and even though it is winter they are busy out of doors for most of the day, tapping trees for maple syrup, but more usually spilling out of car hulks that they work to resuscitate. They hurtle past the lens on skis or cars or sleighs, laughing and falling over and having a good-old-boy time. No one is getting dressed for work or school or bending over seedlings or getting framed up into architectures reserved for growing up or getting old. They look feral, as wild as the animals that are roosting around coops that don’t seem much different than the big old house they all live inside. How many of them are there? Twenty-odd, maybe more. Frank talks to them behind his camera shield, asking good-humoured questions that sound like straight-man chatter from one of the Apollo missions. They eat it up, of course. They call him “Frankie,” they put it on a little bit, but always there is life happening while the camera rolls. An Elvis song is struck up and down, and there is a summons for dinner, all those faces pooling in the natural light, asking, “What next?”

In the end they gather for a family portrait out of doors, the boys and girls and young ones and mother calling out for those still tending to some off screen moment while the camera keeps on rolling. There is nothing frozen or stillborn or lost, no summary glance. Perhaps in the end there is nothing to add up, only another glimpse into a home life, parts of the long home movie that Frank was busy making whenever he turned on the camera.

A Life

75 minutes, colour, 16mm, 1986

Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, Chris Burden… Frank Cole? Yes, with this movie Frank comes out as a performance artist extraordinaire. His body, like theirs, is a machine for producing pictures.

Frank’s nearly wordless solo performance for camera finds him back-and-forthing between a horizonless Sahara and a room that contains only a desk and a bed. His double life is insistently crosscut in rhyming movements, as if he were in two places at once. Every moment is choreographed and rehearsed, so what we are seeing is never the thing itself, but instead an echo or double of that moment. Even when we are seeing a simple action like lighting a match or walking across a room, we are watching a performance of that action, instead of the action itself. A set of architectural drawings map out his room and the gestural vocabulary it might contain, a scored choreography that anticipates movements that never occur for the first time.

In the desert, ground swallows figure again and again. This reconfiguration of foreground and background becomes, in Frank’s cosmology, a consideration of life and death. Death is the ground against which we cast our shadows, every sandy footfall a temporary intrusion. When a vial of his grandfather’s ashes breaks in Frank’s room, he sweeps it up and eats it. But in the desert it is the merely human who is swept from one dune to the next, overtaken and digested.

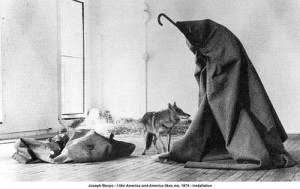

Joseph Beuys famously performed with a wild coyote in Coyote: I Love America and America Loves Me (1974). For a week Beuys lived in an art-gallery cage with an untrained animal, wrapped in felt whenever necessary to ward off unwanted attentions. Beuys had his coyote, Frank his snake. The large reptile slithers across his bed and floor, where he takes hold of it and then releases it, confronting it again and again. Finally he becomes the snake, emerging as a slithering mass across the desert and then the floor of his room, smeared in blood.

Life Without Death

83 minutes, colour, 16mm, 2000

Life Without Death appears as a sequel or extended coda to A Life. Once more the film opens with an image of Cole’s beloved grandfather Frank Howard, whose absence requires another penitential voyage across the Sahara. Before the death of his grandparents, there was no need to produce doubles of the world, but once the wound is open the pictures flow in an attempt to cover what is missing. The wrapping, the bandage, the stanchion: it’s never enough.

While A Life issues a combination of landscape and performance art, LWD is a distinctly linear travelogue narrative of crossing the Sahara, accompanied by voice-over narration. The story Cole relates is simple enough: the search for water, the desertion of his guides, getting lost, the struggle with fear and loneliness.

The cinematography is precise and rendered always in the first person, offering picture-perfect landscapes from the solidity of three legs or else a lilting view on top of a camel. Impossibly, owing to his largely solitary travel, Cole shoots his voyaging with a wind-up camera and a timer, so that he can step in front of the lens and perform himself. There are periodic returns throughout his trek to moments that might be outtakes from his first film, showing his grandfather looking out a window, or lying in bed. Again and again these two figures are married via montage, one gesture rhyming another. Frank lies down and his grandfather likewise; they are finding their home together in the world of pictures.

In the end, having crossed the Sahara, he kneels beside his camel as they look out at their Red Sea destination. Frank says, “Alive.” It was the last word he would ever speak on film.