Patrick Jenkins by Martha Fleming

The Funnel Experimental Film Theatre March 6, 1981

Originally published in Vanguard Magazine, Spring 1981

Check out Patrick’s excellent website for much more. http://www.interlog.com/~pjenkins/

The first Patrick Jenkins film I saw was the first film Jenkins ever made to show. Called Wedding Before Me, it was made in 1976 from ‘found footage’ of Jenkins’ parents’ wedding in a rural town in Southern Ontario. The garish, early satin colours of bridesmaids’ dresses had discoloured as the film had aged and Jenkins, by manipulating both speed and forward/reverse projection of the film itself, managed to uncover the macabre, predatory nature of the ritual. Kisses become tooth-bared attacks, and the wind blowing a veil a semaphoric signal to action out of an eerie, yellowed history.

Five years later Ruse (Super 8, sound, 7 minutes), A Sense of Spatial Organization (Super 8, silent, 25 minutes) and Shadowplay (Super 8, sound, 10 minutes) was shown in Toronto in March in that chronological order (and available for screenings and distribution from the artist at Apt. 167 – 798 Richmond St. W. Toronto) and form a progression that both parentheticizes and accentuates the middle film.

Ruse is a romantic film, heavily edited and comprised of images of three-dimensional things that admit their two dimensionality under the pressure of camera movement. The eye tends to compensate for the flatness of the projection screen, and when the image of a shaft of light disappearing into a room corner appears on it, the viewer is prepared to invest trust in his/her ability to march up to the screen and put his/her fist into that corner. But when Jenkins suddenly rotates the camera, the light shaft relocates from the corner and flattens out to the dimensions of the screen itself, becoming an abstracted white bar travelling around the frame of the projection.

Dense with thick colours and a musically pensive soundtrack, the crimson romanticism of images such as light beams tends to undercut the more interesting exploratory elements of Ruse.

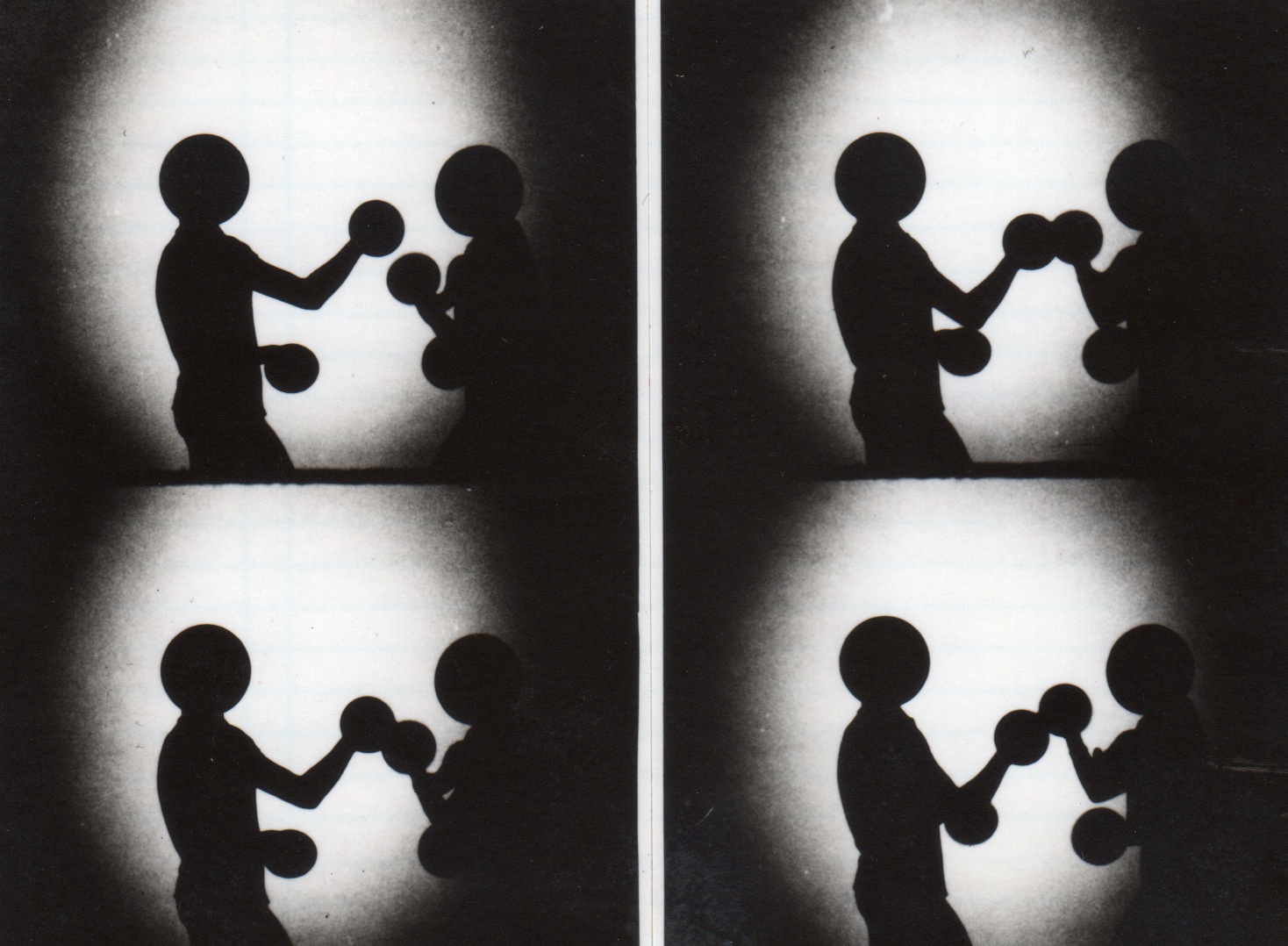

Shadowplay – the third film Jenkins showed that night – suffers from some of the same tendencies, but is more interesting because of Jenkins’ use of (you guessed it) shadows, and a consequent flirtation with drama and the sense of character narrative. This film also has a musical soundtrack, though the audio here is much more contrapuntally suited to Shadowplay than Ruse’s soundtrack is suited to it. Highly dramatic, very anticipatory, the music in Shadowplay becomes a syntactic element in the implication of ‘story.’ Whereas in Ruse the sound attempts to reconcile the edits in the film, gloss them over through distraction, in Shadowplay the audiotrack is an integral part of the work.

Camera dissolves move the viewer in and out of a miniature cardboard set, introducing characters in the form of shadow and complementing silhouette. Toying with scale and dimensional perceptions, Jenkins invites the tale-trained mind to pick up these threads, as we strain to find the plot. A Sense of Spatial Organization, the most interesting of the three films, seems to have been a stocktaking venture before Jenkins plunged into the kinds of stagey – and, for experimental film, unorthodox – concerns that Shadowplay evidences.

Twenty-five minutes long and notably silent, Spatial Organization presages Shadowplay in that it is divided into ‘chapters.’ Each one is a witty demonstration of the quality of film and the nature of perception. A structural film made to conform to the ordering practice of narration, it comments amusingly on the opposing axes film is hung on. For traditional film to maintain a theatrical suspension of disbelief, it must never allude to the fact that its trickery works on many levels to effect that suspension. One of the bases of experimental film is to undercut that literary tradition and make the film – as film – responsible to itself rather than to audience desire fulfillment. Jibing both ‘schools,’ Jenkins makes the recalcitrant oppositions look each other in the eye and shake hands.

In the chapter “Measurement,” Jenkins lays a yardstick down on a page and proceeds to draw two lines, one from the two inch mark and one from the three inch mark, crossing them with a line at the middle of the height of the lines. As he draws two longer lines up from the 1.5 inch mark and the 3.5 inch mark and connects them as well, we note that measurement is relative in more ways than one – we know that the two lines between the marks are of differing lengths, but because they don’t start in the same place it is difficult to tell with the eye just how much longer. Later in the film, in the chapter “Green” during a pastoral moment as the camera pans a park, a football goalpost appears in the corner of the frame, snagging a memory of the “H” Jenkins made in the “Measurement” chapter.

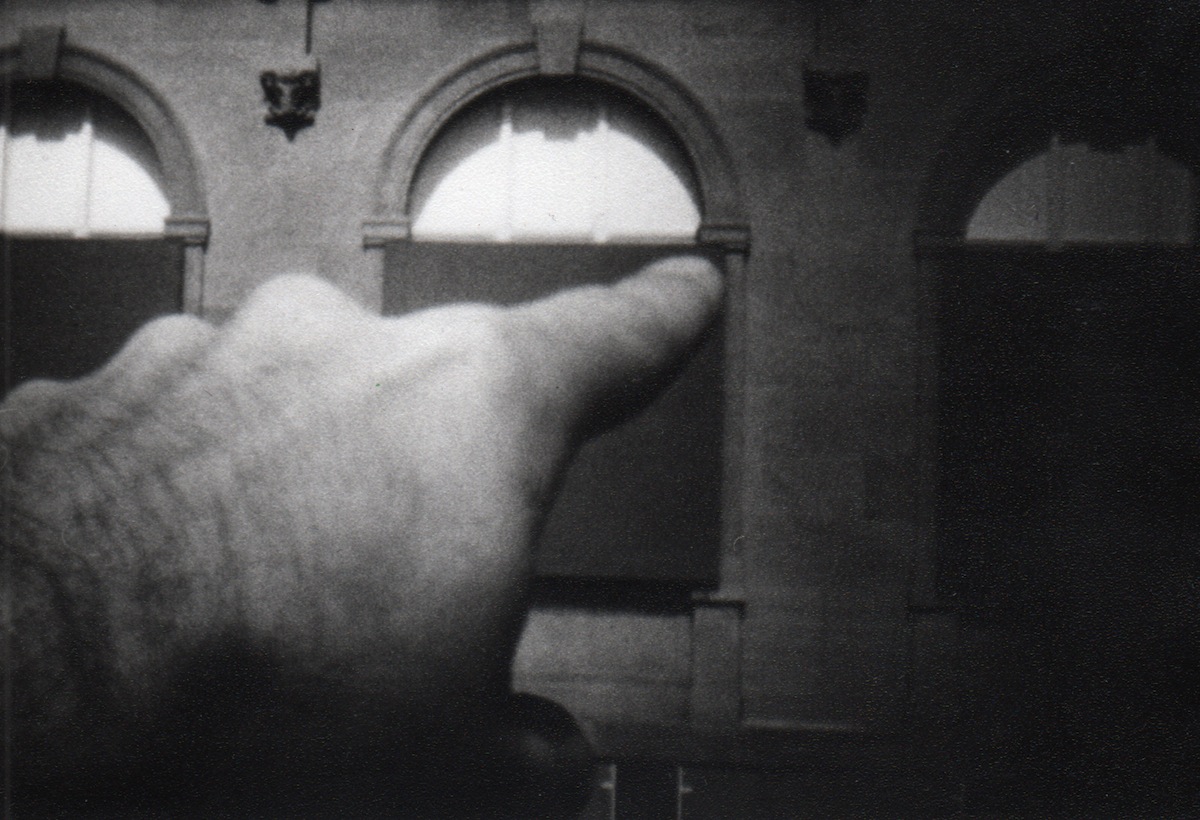

In “Sightline” Jenkins fills the frame almost full with the green awning covering a widow. Suddenly an awesomely large hand comes into the picture and points out the delineation of the awning; a square within a square. A gap is opened up between the plane of the projection on the screen and the similar plane of the awning within it, cross-dimensionally mediated by the hand and the finger that lies between. Strangely, it points as much to the film we are watching as to the awning which is its central image, the depth between cameraman and object parallels our relationship to the film screen.

In the “Duration” chapter, two metronomes tick at first in unison and then are adjusted to be at different speeds, alluding humorously to story-time and discourse-time, or the difference between the time and sequence of an actual event, and the time and sequence of the retelling of the same event. “Unity” attempts to sew a number of these component ‘demonstrations’ together. Attaching the “Movement” metaphor of a 3D postcard of a spider moving back and forth to the bar of a ticking metronome, Jenkins tosses the coloured rubber balls and tiles of the “Colour” section against it, delivering the punchline to a pretty good joke.