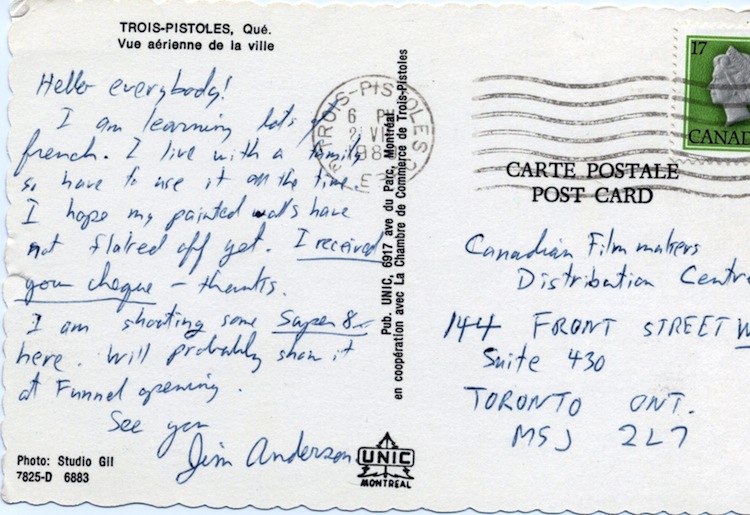

James Anderson: A Chronology of Work by Anna Gronau (Funnel Newsletter March/April 1981)

Films by Jim Anderson at the Funnel February 22, 1980

Repetition and the Site of the Reel by Dot Tuer

(C Magazine, Summer 1985)

James Anderson: A Chronology of Work by Anna Gronau

Originally published in the Funnel Newsletter Volume 4, Number 3, March/April 1981

In the Toronto “art scene” James Anderson is perhaps best known for his drawings and paintings. In the past year he has exhibited as part of a three person show at Mercer Union with Oliver Girling and Andy Fabo; his work was included in the recent “Monumental” show; and he also participated in the “O Kromazone” exhibition organized by Chromazone gallery in reaction to the concurrent “O Kanada” show in West Berlin. Last month, his work was part of a group show featuring works from the drawing workshop of six Toronto artists, at the Quan Gallery in Toronto.

And yet, James Anderson’s major works have been executed not in the graphic media, but in film, and they have been produced, not only in the last three years, but over more than a decade. Little or nothing has been written about the work of this important Canadian film artist, and with the event of his first solo exhibition in New York City at the Collective for Living Cinema on February 4, has come the time to set the record straight.

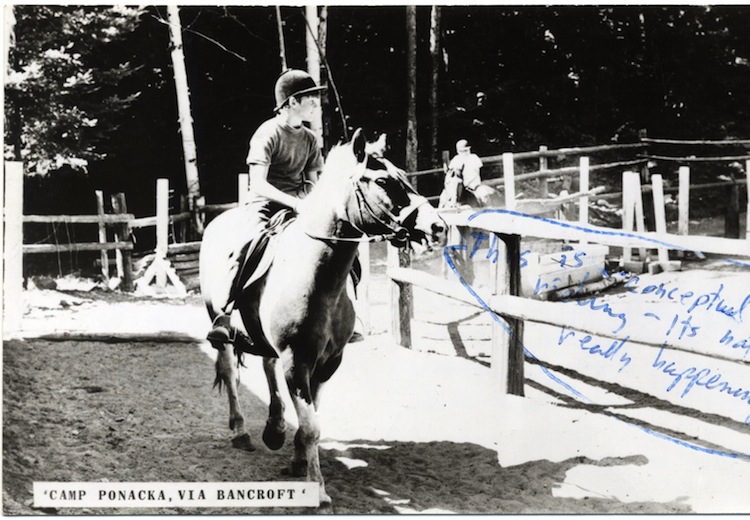

Anderson began to make films in high school, when he and friend Keith Lock produced films instead of essays for some classes. He describes these early pieces now as “superficial teenage obsessions” but does note that one piece that they produced, a three-screen, Super 8 version of “Waiting for Godot” was a definite precursor to his later experimental approach. Although the film is lost, it seems, from its description, to have had a precociously advanced grasp of formal principles, using ideas of anticipation and repetition to achieve its effect.

Lock and Anderson worked closely for a number of years and were subject to the same influences for most of that time. Anderson recalls seeing Warhol’s “Chelsea Girls” at the Royal Ontario Museum and having noticed that it was “still working on me” several days later. The two enrolled in a film workshop at the Three Schools, which was being taught by Ian Ewing. Ewing was extremely enthusiastic, and though he had almost no equipment with which to instruct his students, he invited his friends, people like David Cronenberg, to class to talk, and showed a great many films.

As young filmmakers with no equipment and no money, Anderson and Lock were not daunted, and took it upon themselves to make the least expensive films that they could – they painted directly onto clear 16mm leader. In 1969, his six-minute animated film, “Scream of a Butterfly” received a prize for best animation at the first Canadian Student Film Fetival held at Cinecity in Toronto. The film went on to win the grand prize at the tenth Muse International Student Film Festival, in Amsterdam, later that year.

Following high school, both James and Keith enrolled at York University in the film course of the Fine Arts Department. Despite its affiliation with the Arts courses, the film section did have a decidedly industrial slant, according to James, but they were exposed to the “classics” and at one point saw some films by British experimental filmmakers like Malcolm Le Grice when Annabelle Nicholson from the London Filmmaker’s Co-op visited the school. While students James and Keith completed another animated film called “Base Tranquility” and a short dramatic work called “Arnold.”

After two years of university, Anderson felt compelled to leave his studies behind for a time. He and his brother David became involved in the Toronto theatre scene, with David working on sets and James projecting films for various theatrical works at Theatre Passe Muraille. For plays such as Paul Thompson’s “Ubu Raw” he produced short films that were used as part of the dramatic work.

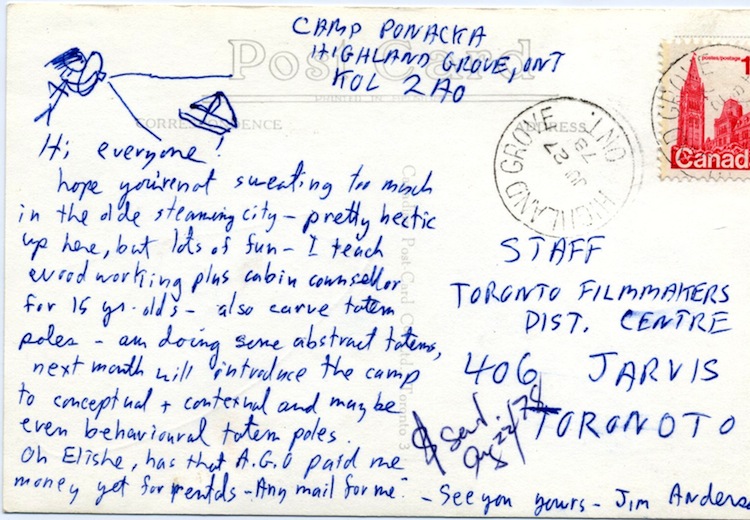

In the early seventies, the Toronto Filmmakers’ Co-op started, along with the Filmmakers’ Distribution Centre. James was hired, although he claims he doesn’t know how it happened, as a workshop co-ordinator. It was in the days of O.F.Y. grants (Opportunities for Youth) and so for six months, James had the opportunity of running workshops at the Co-op. The opportunity (and the salary) were shared by Keith Lock. During that time Anderson saw films that he lists as extremely influential. They were works by Snow, Wieland, Mekas, and Brakhage, as well as films by people like Jack Chambers, Greg Curnoe and John MacGregor, less well-known as filmmakers, but fairly active in film at that time.

Anderson produced two films during his stint at the Co-op. They were “Yonge Street” and “R.O.M.”, both of which were produced quickly and cheaply, using out-of-date film. In the summer of 1971, Keith and James did their last project as a team. It was also James’ last dramatic piece, a sequel to “Arnold”. Keith was still at school, “so he could use the editing room”, and over the next year the two edited and completed “Work, Bike and Eat.”

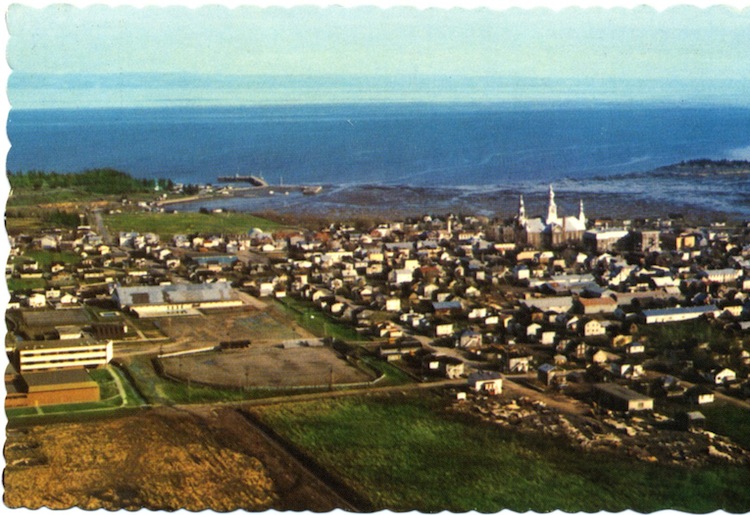

In 1972, James and Keith, as well as David Anderson and their friend Anna Gronau, both students at the Ontario College of Art, moved to a communal farm north of Orillia, at Buck Lake. Keith began work on his film “Everything Everywhere Alive Again”, and James worked for a number of months before embarking on a trip that had been planned for some time. It was a “mythical journey” for him. With a tiny Keystone camera he travelled by bicycle to Thunder Bay, shooting as he went, very often from his moving bicycle. Influenced by Wieland’s “Reason Over Passion” he hoped to make a sort of travelogue which would reveal the story of his odyssey. In the fall, the journey complete, he began to compile the footage at the Co-op. He recalls the primitive editing facilities there, but notes that there was a very loose, easy, accessible atmosphere. Grenada Gazelle, (her General Idea name) was working at the Co-op at the time and was very helpful.

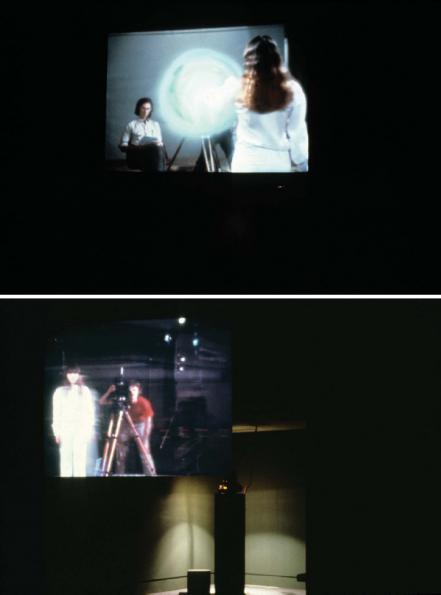

But the planned twenty-minute travelogue began to raise problems and Anderson planned ways to solve them through intercutting other footage which he thought he would shoot in the city, recreating scenes from his diary. There was a lot of excitement at that time about structural film, and Anderson felt that his film might be too “Jonas Mekas” or subjective. He liked films like “Wavelength” and “Back and Forth”, and around that time had begun, with Keith Lock, to do some camera work for Michael Snow. They shot the airplane sequence for “Rameau’s Nephew…” and saw rushes of the film in Snow’s basement studio. Anderson was impressed by Snow’s approach. He was “totally rigorous, but not academic or dry”; he represented the “essential figure” of filmmaking for Anderson, because, in Anderson’s works, “Snow really pursued possibilities to the end.” All this had an effect on the film that was in progress. It was a major decision to abandon the tyranny of trying to re-create the experience of the trip, and though liberating, it was also difficult, given the importance that trip had had. Anderson decided to divide the film up into sections and chapters. The travelogue section became one of several. Ideas about film as film, naming, the meaning of photography, developed from Snow, Wieland, and Godard, began to shape the film. By the time Keith and James helped Snow to shoot his installation “Two Sides to Every Story”, the formalist approach was well established as a part of the work in progress.

Much of the footage for the work which would finally be called “Gravity is not Sad but Glad” was shot in Anderson’s room on Dupont St. With a room, now that could be used as a studio, his drawing and painting began to flourish. The room became a studio, set, gallery and museum combined. The paintings from that time reflect a Pop sensibility, borrowing from Rauschenberg but perhaps less urban and akin to Curnoe. The scenes for “Gravity” that were shot there reveal the accumulation of objects and ideas, consumer “junk” items like cheap toys, commercial packaging, and so on that were starting to creep into what had originally been a simple travelogue.

Unlike many of the other filmmakers who were working through the Filmmakers’ co-op then, Anderson’s influences were drawn from the art world and less from the film industry. Among the people he worked with were Michael Snow, and Peter Dudar and Lily Eng of Missing Associates, the dance/performance artists.

Finally, in 1975, James received a Canada Council grant for $1500 and was able to get a print of the completed film. The film was over two and a half hours long, and the artist was both shocked and excited by the sheer bulk of it. Encouraged by Snow’s epic film “Rameau’s Nephew…” he showed it to a small group of filmmakers and friends at the Co-op. The response was less than overwhelmingly positive. Although some people found certain sections amusing, the general consensus was that it was “too long.”

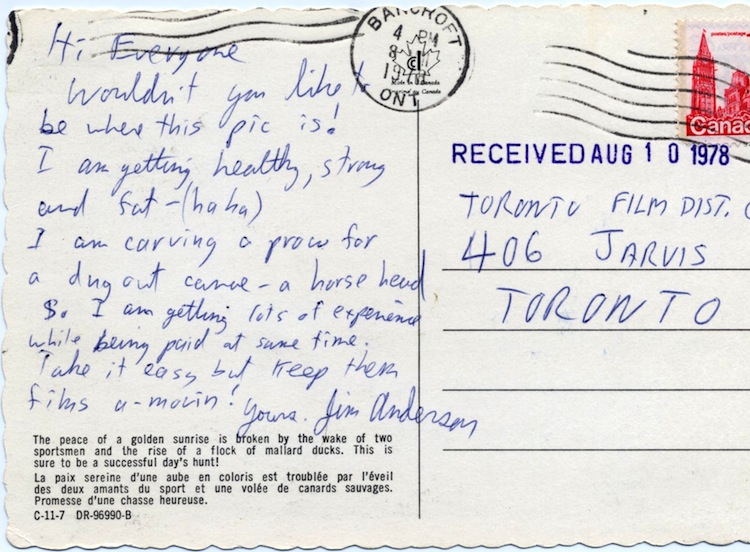

The next morning, Anderson began to cut the film again. He removed the section shot during his trip and made it a separate film called “Moving Bicycle Picture”, a move he found painful, but necessary. He removed other sections in their entirety. For a while he stopped working on films altogether, took some odd jobs and confined his creative output to drawing and wood-carving and painting miniatures in oils.

In 1977, a kind of rekindling interest in experimental film began. On Duncan St. the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication began its film programme which later became the Funnel. A block away, Keith Lock and David Anderson, who were sharing a studio, started a series of film screenings in their studio. Some of the people who showed their films there included Ross McLaren, Betty Ferguson, John Massey, Villem Teder, and Peter Chapman. At one of these screenings, “Gravity” was finally shown again. For the first time Michael Snow saw the film and was enthusiastic. It was an encouraging event, after the film’s dismal debut, several years earlier.

When the Funnel began in earnest, the group of filmmakers who had been involved in the John Street screenings joined with the Funnel, and there was, in Anderson’s words, “a real community formed.”

After a year in Europe, Anderson returned and became involved with the Funnel as a Board Member. He returned to University and began to do more visual art. In 1980 he had his “first film screening in a real theatre” at the Funnel, as well as his first gallery show there. The screening was a retrospective of earlier work and included re-worked footage discarded from “Gravity” and combined with performance. The gallery work was a development of themes and ideas gleaned from Pop Art, with the beginning of an idea of totems or objects imbued with deep character or symbolic and ritual meaning.

In 1981, there was even more reaching back and tying up earlier works. Since 1973 Anderson had made occasional pilgrimages to Queen’s Park in the heart of Toronto to film a certain tree. With this collection of footage he produced the film “Le Bois de Balzac” which was recently featured in the show at the Collective in New York. Like “Gravity” this film has a relation to nature which defies sentimentality, and confronts the idea of a “dialogue with nature” as a cure for humanity’s ills. While there is an affection for nature it is with a constant awareness of the intervening human mind that it is shown. “Le Bois de Balzac” tries to break down some of the “structuralist” ideas which had left the filmmaker feeling “painted into a corner” by the time the 1980s started. The tree which remains always the centre of the film echoes the totemic references in the drawings, and forecasts some of the mythological ideas (particularly Christian) in later works on paper, such as “Sandino and Moses” a piece exhibited at the Funnel Gallery in 1981.

Anderson’s current projects include compiling and re-working even more earlier footage, and embarking on some Super 8 work exploring the human presence in film. There has been a steadily increasing interest in his work both as a draughtsman and painter, and as a filmmaker. The foregoing is not meant to provide any kind of in-depth analysis of Anderson’s films, nor to heroicize the artist himself. Rather, it hopes to call attention to the committed endeavour and several works of major importance of his artist which, because of lack of institutional and critical support, could go unnoticed, otherwise.

Anna Gronau

Films by Jim Anderson at the Funnel February 22, 1980

Sailing Around This/The World 1980 Colour A Short of indeterminate length

…in progress as you enter

This film/shadow begins to throw out a multitude of surprises… or at least it did to my tired mind late last night. Magellan, the first man to sail around the world, seeing strange new lands but his men dying of cold and scurvy… modern day loners circling earth in tiny rigs… the earth as a bull… the earth as apple… Columbus watches butterfly on apple… sees that the earth is curved… is round… apple falling.. is it gravity?… Coke can falling… Coca Cola now encircles the globe – found everywhere – … the delicious and sublime words of the shadow title… the cast shadow as primitive image projector… flickering shadows on cave walls.

Concorde 1980 Colour

…in a sense a continuation of Sailing Around the World. Now we do it in a few hours; but what a concentration and dispersement of energy over a few hours. In this film, sound suggests motion, energy rather than the image. Film is image, Film is sound, sometimes film is both these things together.

Moving Bicycle Picture 1978 Colour, Silent, 12 min.

…again travelling, but now what is seen from the moving bicycle. I omit important events like eating and camping. After a time the camera, bicycle, and myself become entangled, involved, friends and enemies. The shadow on the road makes us all one.

Big Key 1972 B&W 8 min.

A pianist repeatedly stumbles over a passage of music and vents his frustration in antics that become increasingly ridiculous and divorced from the original cause. This film probably demonstrates a particularly Western way of dealing with anger and frustration. A Chinese friend of mine once said to me after I had thrown some appropriate words at a faulty car engine; “I can never understand how you yell at an inanimate object.”

Canada Mini-Notes 1975 colour, 15 min.

The flip books become a demonstration or enactment of film perception (ie, still images rapidly following one another). The flipbook becomes a movie about a book and/or a book about a movie. The flip book is everyone’s home movie (or book). Like The Big Key the flip books become progressively more ridiculous but hopefully this apparent absurdity will not detract from a certain seriousness in my intent to expose some characteristics of the film medium, such as light, colour, motion, depth, frame, sound and narrative.

Intermission

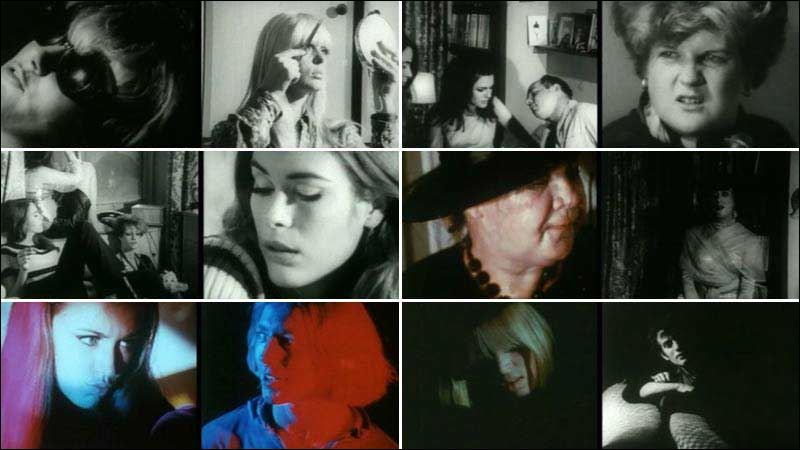

Work, Bike and Eat 1972 B&W 40 min. Made in conjunction with Keith Lock

“The further adventures of Arnold as he copes with shop lifters, family dinners, beer fights, hush puppy stories, infantile bikers and brief encounters.” Jim Murphy

The film maintains a risky course between domestic documentary, staged rehearsed acting, scripted cinema-verité, and absolute cinema-verité. Sometimes we did a scene with exact dialogue and movements, other times we let the inherent personalities of the people be revealed. The challenge was to meld all these styles into a unified whole. This, in fact, lead us to change so called cinema-verité scenes by cutting or adding words, or by the use of out of context reaction shots. On the other hand the staged scenes were sometimes too stiff so we had to doctor these too. I think I had started out idealistically with the idea of capturing reality with little interference, but we ended up realizing that the techniques associated with cinema verité often capture less of the real reality. The film also shows a real mix of both of our experiences put into one character. Keith had really worked in a drug store; I really had inane beer parties and both of us had really loved to cruise endlessly around the city on our bikes.

Repetition and the Site of the Reel by Dot Tuer

Originally published in C Magazine, Summer 1985

An examination of a film by Jim Anderson: Bois de Balzac; 16mm, black and white/colour, sound, 1973-81; Distributed by the Funnel and the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre

There are four legends concerning Prometheus: According to the first, he was clamped to a rock in the Caucasus for betraying the secrets of the gods to men, and the gods sent eagles to feed on his liver, which was perpetually renewed…

In the opening sequence of Bois de Balzac, what appears to the viewer as an aerial pan of a distant earth sharpens into focus and reveals a close-up of the gnarled bark of a tree trunk. The camera movement, in turn, is revealed as a spiraling action as it encircles the tree, moving outwards from the trunk, upwards through the branches, towards an empty sky.

According to the second, Prometheus, goaded by the pain of tearing beaks, pressed himself deeper and deeper into the rock until he became one with it…

The implications of this opening sequence can be read as metaphysical. The tree functions as a symbol of a Lost Paradise; the camera’s path represents the order of a renaissance universe; there is a phenomenological merger of the filmmaker and nature, of the spectator and space.

According to the third, his treachery was forgotten in the course of thousands of years, the gods forgotten, he himself forgotten…

Yet this moment of philosophical cognition is as quickly ruptured for the viewer as it is fleetingly grasped. A voice-over displaces the metaphysical signification, intoning “once upon a time… Belgrade 1950.” This specificity is in turn displaced by the naming of other cities, other dates. Disparate sounds, narrative fragments, voices of people, descriptions of objects that never appear, in turn disrupt the mapping of space. Our attention is directed to the immediacy of the image “…see the squirrels sitting on the branch,” misdirected by their absence from the visual frame of the film.

According to the fourth, everyone grew weary of the affair. The gods grew weary, the eagles grew weary, the wound closed wearily…

While the camera’s continuous spiraling and encircling motions define the sculptural and representational properties of a particular tree in Queen’s Park, Toronto, the soundtrack occludes its materiality. Enveloped by wisps of voices, sounds, music, and names, the visual rhythms of the camera become caught, contained. The eyes can shut but not the ears. And so narrative becomes the interloper, disturbing modern space and dispersing temporality with fragmentary recollections of the subject’s desire to layer meaning upon vision.

But there remained the inexplicable mass of rock. The legend tried to explain the inexplicable. As it came out of a substratum of truth it had in turn to end in the inexplicable.1

In her book, Passages in Modern Sculpture, Rosalind Krauss begins her examination of modern sculpture with Auguste Rodin and ends with Robert Smithson. She traces its origin in the transformation of meaning from a classical economy of an internal narrative to a surface abstraction in Rodin’s Gates of Hell. She locates its apotheosis in the movement from a “static, idealized medium to a temporal, material one”2 embodied in Smithson’s monumental wharf of earth: the Spiral Jetty. Within the parameters of Smithson’s work, Krauss experiences an immediacy which has eschewed narrative, a “moment-to-moment passage through space and time”3 that supplants historical formulas. Yet, in Krauss’s conjoining of immediacy and passage she produces anew the historical formula of modernism. Severing her investment in Western art history by identifying minimalism and abstraction as a radical break with the past, she rehabilitates the discourse of the modernist avant-garde. Her paradigm disposes of the signified in favour of the primary signifier—the material presence of the art object—but constructs this paradigm on a chain of historical and philosophical signifieds, a progression of sculptural moments that interlock location, production, and reception to frame objects as art. And by designating the contemporary significance of sculpture as traces of the body’s “presence” upon the surface of the medium, she evades the issue of social space. For in both the public monument of the Renaissance and the site-specific earthwork of contemporary America, formal strategies are inextricably intertwined with political narratives.

The Renaissance statue or fresco communicated to its viewers a symbolic structure that represented a city-politic and a state-sanctioned religion, a structure that Krauss designates as the internal narrative. On the other hand, the modern earthwork as framed by Krauss in relation to abstraction assumes a role within her criticism that deflects an internal narrative. Yet the site- specific sculpture is not an object unto itself and nature, but a contextual operation. It exists within a culture that promotes image over substance, that veils ideological alignments through championing individualism, and that disguises formalism by advocating pluralism. And so I distrust, not the validity of Spiral Jetty as an artwork, but Smithson’s insistence— and Krauss’s endorsement— that in his earthwork “no ideas, no concepts, no structures, no abstractions could hold themselves together in the actuality of that phenomenological evidence.”4 For I imagine, in a moment of immediacy removed from Krauss’s paradigm, the reaction of a traveller who happens upon this inexplicable mass of earth. I suspect that this traveller would desire to affix a narrative, a legend, or a fiction to “phenomenological evidence” in order to locate him/herself in a relation of meaning to this object. A mystic might overlay a myth of creation upon the spiraling mass. A tourist might wonder when the new McDonald’s was going to be built to augment its attraction. An historian could derive a cultural metaphor for America’s manifest destiny and its frontier imperative to mark the conquest of territory. A scientist would search for its practical relation to air and water currents. A cynic might wonder why anyone had bothered to remake nature. But to experience the spectating activity of the earthwork as a radical de-centering in and of itself, as Krauss proposes, one must pre-suppose the idealization of the centered being. Krauss’ imaginary viewer must exist as a Cartesian subject, a “modern” individual for whom perception is unmediated by their social construction within symbolic discourse, and for whom the history of Western art has become an everyman’s language for “seeing” objects as art. It is these assumptions that Anderson questions in his film Bois de Balzac.

If it had been possible to build the tower of Babel without ascending it, the work would have been permitted.5

Like Smithson, Anderson is the producer of a spatial configuration that spirals between earth and sky. The difference between them lies in how his cinematic encirclement of a tree for forty-two minutes inverses the apprehension of the object’s materiality. Rather than affirming the tree’s presence as phenomenological evidence, Anderson is concerned with mapping its relationship to language through the disjunctive narrative of the soundtrack and incessant camera movements. By displacing the “presence” of the tree that is at the centre of the cinematic frame, the film undermines the idea of perception as an immediate and unmediated “seeing,” becoming instead an exploration of why we desire this immediacy. In Bois de Balzac, it is absence, or rather, the impossibility of presence, which positions the subject. The tree functions not as a primary signifier, but as a continuously mediated object, an object of repetition that splits rather than de- centers the spectator. In so doing, Anderson’s film is concerned with the psychoanalytical “real” of the unconscious rather than a constitutive presence. This is a “real” which is veiled by representation, and which is ultimately unknowable. The camera’s motion becomes an approximation of the child’s ‘fort-da’ play, which Sigmund Freud identified as pivotal to our passage from a primary separation of self and other to relational space and time. In the game, the child throws a spool or reel of thread across the room whenever his mother leaves the room. Flinging it away from him, he says ‘there;’ pulling it towards him, he announces ‘here.’ The reel stands in for what is missing (the mother), concealing the recognition of absence. In a parallel fashion, Anderson’s centrifugal tracing of the tree, which announces its presence while representing its absence, evokes the profound anxiety of the subject’s primary separation. It documents, not our encounter with the “real,” but that first missed encounter, in which we turn to objects to narrate loss.

I am frightened and astonished to see myself here rather than there, for there is no reason why here rather than there, why now rather than then.6

The orbiting of Anderson’s camera, which closely circles the tree, expands in diameter until its varying speeds and movements resemble the paths of planets in an immense and complex solar system. The image of the tree, while remaining the physical centre of the frame, becomes lost in the foliage and surroundings of the park. The camera inadvertently documents a boisterous parade marching upon the road that encircles the trees in the park. This is the only visible crowd scene in the film: a group of middle-aged Shriners dressed up as Indians. Anonymous voices interject descriptions of other gatherings before and after the frame is emptied of the parade. On a summer day, we hear that “a crowd of students is passing, they shout football cheers.” In the early morning, we hear a whistle, and then a voice telling us to “see the large crowd of people marching through the trees. Some are holding signs. There is a large effigy of a head. It is now burning. People are shouting, ‘We will be free. We will be free. We will be free.’” At another moment it is night. The spiral web of the camera intersperses close-ups of the trunk with the slippery zigzag of a slip moon and the dotted lights of downtown buildings. Throughout the film a voiceover repeats a description of an encounter we never witness, where a man approaches a woman standing by the tree and they go off together. This repetition, intertwined with glimpses of people, fragments of stories and events, conversations between friends, populates an imaginary history of the tree. Yet despite the density of social interaction created by the soundtrack, a sense of emotional dislocation grows as the camera moves relentlessly further from the tree. Suddenly, private whispers of voices compound a feeling of anxiety. Snippets of their words, “Help me… help me… bags and bags of dirt, many, many bags of earth,” evoke an atmosphere of suffocation for the listener, no longer able to comprehend the inaudible gist of murmurs. Only in those moments when the camera returns to a recognizable outline of the tree does this sense of dislocation subside.

Why do we lament over the fall of man? We were not driven from Paradise because of it, but because of the Tree of Life, that we might not eat.7

Paradoxically, it is not the camera’s motion, the continuous spirals, that produces a sensation of dislocation. Rather, it is the inaccessibility of the tree that provokes what appears to be a spatial disorientation. Although the camera never deviates from a rigid structure that at all times signifies the tree as the centre of the frame, it never comes to rest upon the tree. The camera returns again and again to the tree, yet the tree never looks the same. The descriptions of imagined and actual events infuse perceptual space with contradictions. The tree’s permutations become as endless as the spirals and sounds that engulf. These subtle interrelationships of what we see and cannot see produce a spectating activity where the viewer is inscribed into a pattern of repetition that seeks the memory of an object that cannot be remembered. This is not the repetition of a structuralist premise that pursues a visual purity, but the repetition of the analysand engaged in the search for the absent moment that has constituted his/her presence in a symbolically structured universe of language and social space. As a situational repetition constructed through an overlay of spatial and discursive moments, the film entices the viewer to know the tree, and by its very mechanism, eludes recognition. For if it were possible, as Krauss suggests, to know the object in a moment of immediacy, the subject would have returned to the moment of splitting: a moment before language and after birth where social space does not exist. And to return to this moment, to position oneself at the site of the “real,” is to enter a space that we call madness. What Anderson’s film reveals as “presence” is a play of signifiers that divests the subject of a primary anxiety. For it is at those moments in the film where the tree is most obscured that the viewer apprehends the radical significance of absence framing presence.

Leopards break into the temple and drink to the dregs what is in the sacrificial pitchers; this is repeated over and over again; finally it can be calculated in advance, and it becomes part of the ceremony.8

In Questions of Cinema, Stephen Heath proposes that “structuralist/materialist film has “no place for the look. Ceaselessly displaced, outphased, a problem of seeing; it is anti-voyeuristic.”9 Despite this seemingly laudable characteristic of the cinematic genre, Heath finds its intentional evasion of “the look” problematic. He argues that the structuralist/materialist project to employ repetition as a framing device, to locate the subject outside of the economy of narrative, becomes a “defined and limited project with its own confirmed audience – and its own cultural trap.” This charge of a closed system, of a moribund modernism, is what Anderson addresses by re-framing repetition as a problem of language. When Anderson began in Bois de Balzac in 1973, earthworks and durational cinema were in their heyday of cultural validation. Michael Snow’s La Region Centrale (1971) was critically embraced as the final word in a revolution of cinematic perception. For it was in this film that the viewer became divested of all relation to a social construction of “seeing” to become the absolute centre of vision, the literal eye of a mechanical apparatus that was programmed to move the camera in all directions around an empty landscape in northern Quebec for three hours, while a soundtrack synchronized and composed from the original sound of the camera device punctuated the spatial apprehension of the viewer’s vision. By fusing the viewer and the camera motion as an undivided presence in nature, any social or political significance of his/her position in the world became nullified. The problematic of “seeing” became reduced to a formalist strategy, to a philosophically determined investigation of visual purity. As such, the radical properties of the film demanded a continuous and rigorous displacement of the subject’s investment in the construction of narrative. La Region Centrale became the pinnacle of a modernist revolution in the art object: a revolution that divorced aesthetics from politics and cornered the viewer in a formal space divested of all symbolic significance.

As for the significance which repetition has in a given case, much can be said without incurring the charge of repetition.10

Anderson’s film, on the other hand, explores the conjunction of formal and social constructions of space. In Bois de Balzac there is a “place” for the look, for our desire to fix meaning upon objects in order to constitute a presence in the world. However, this desire for meaning is revealed as that which functions to conceal the primary site of the look: the site of the impossible “real,” the sight of our unconscious realm. As such, the viewer experiences a situation of psychoanalytical transference in Anderson’s film. It is as if he/she is the analyst, the film the analysand. The spiral camerawork, and the soundtrack with its diffuse snatches of memory, its brief dialogues between absent figures who de-populate the frame, its odd noises, its sudden spurts of sound, function as a representation of the desire to reach the presence of the “real.” Like the analyst, the viewer becomes the site of hearing, listening carefully for the convoluted repetitions in a narrative that seeks to uncover the true, hence unknowable, meaning of the tree. In turn, the film’s exploration of our desire to affix an illusive center to an activity of “seeing” while simultaneously revealing the anxiety this desire produces is inextricable from Anderson’s inscription of himself as a subject of this process. Unlike Snow’s camera in La Region Centrale, which functions as a mechanistic device of surveillance that is indifferent to its object, the landscape, Anderson’s camera in Bois de Balzac is hand-held, voluntary in its path. As Anderson returned again and again to film the same tree in Queen’s Park over eight years, the film became less and less an investigation of a cinematic process, and more and more the subject of a personal homage. By transforming repetition into ritual, Anderson’s investment in filming the tree became a manifestation of his own desire to uncover the meaning behind the formalist strategies of the 1970s. Layering imaginary and symbolic fragments of narrative upon his investigation of a singular object, he uncovered the radical diversity of “seeing” that the modernist project held captive through the insistence upon the materiality of perception.

As a continually transfigured and static object, Anderson’s tree functions in defiance of Krauss’s modernist chronology. At one instant it resembles Rodin’s sculpture of Balzac. In another instant, the chiseled torso and face of a woman protrudes mysteriously from the tree trunk, while below the branches of the tree stands an old woman who infuses the cinematic frame with the fleeting powers of an oracle. She calls herself the “Venus of the rags,” fallen to a state of sin, of “loneliness and fright in a strange world.” A hunter “who long ago walked in a forest that once stood here” haunts the frame with his absence. The invisible couple is forever meeting at the centre of the camera’s path, the tree, yet are never seen. Far from emptying the object of his investigation of all internal narrative, Anderson infuses it with a myriad of ghosts and figures, metaphysics and imagination. Yet in so doing, he also subverts the function of representation to enable the viewer to affix a determined meaning upon the object. The fragmentary and elusive events alluded to by the soundtrack allow the viewer to conceptually halt the fluctuating motion of the camera, but only momentarily. The fleeting intersections of what is described but cannot be seen with the spatial demands of the film’s visual structure underscore how narrative encircles a primary trauma of separation. The interspersion of structural and narrative mechanisms creates a spectating activity that opens and closes the gaps between what is knowable and unknowable, between an illusion of unity and presence and the split at the site of the “real” that produces absence. As such, the tree becomes a mapping of the inscriptions of meaning that mediate the subject’s, rather than the object’s, presence in the world. At once a shrine, a statue, a symbol, a fiction, the tree promises neither access to the “real” nor is it framed by a phenomenology of pure “seeing.” Rather, it serves as the site of an interrogation of, and mediation on, modernism’s insistence upon the virtue of unmediated vision.

Endnotes

1. Franz Kafka, Parables and Paradoxes (New York: Schocken Books, 1975), 83.

2. Rosalind Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1983), 282.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Blaise Pascal, Selections From The Thoughts (Illinois: AHM Publishing Corporation, 1965), 10.

6. Kafka, Parables and Paradoxes, 35.

7. Ibid., 29.

8. Ibid., 93.

9. Stephen Heath, Questions of Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1981), 171.

10. Soren Kierkegaard, A Kierkegaard Anthology, edited by Robert Bretall (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1964), 136.