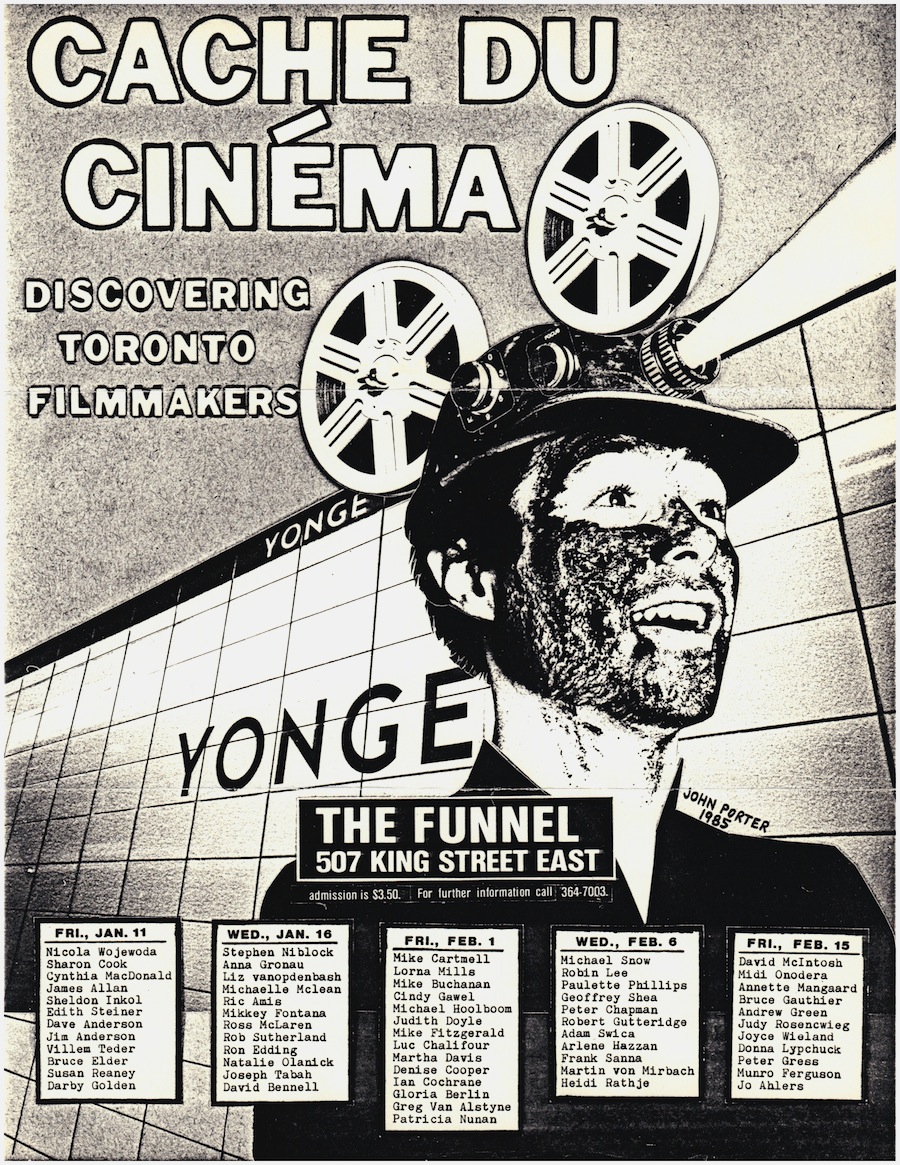

Cache du Cinema: Discovering Toronto Filmmakers by Seth Feldman

The Funnel, Toronto, January 11, 16, February 1, 6, 15

Originally published in Vanguard (May 1985)

Freeing themselves from the usual rites of quality, John Porter, Paul McGowan and Dot Tuer programmed 59 films for the first five screenings of Cache du Cinema: Discovering Toronto Filmmakers. Some established Toronto filmmakers were asked to provide their most obscure films, inevitably their lesser (nay, least) works. The curators themselves found an archival print. But the bulk of the work was, if not student, of student caliber. Before our eyes were people choosing (or not) to take their art seriously, choosing (or not) to understand their own potential. To be generous Cache du Cinema can be seen as a celebration of their prodigious activity. To be honest, much of what was screened manifested the deadening repetition of conceptual art by the mindless. Guilt by association compromised good work by Mike Cartmell, Sharon Cook Susan Reaney, Munro Ferguson, Pascal Sharp, Cindy Gawel and Jo Ahler.

What is surprising about Cache du Cinema is that the series emerged from a selection process at all. Its intent, it would seem from the films themselves, was simply to compensate for the Funnel’s open screenings, long since banned by the Ontario censors. Whatever ended up on the projector could at least be justified as sacrifice to the weary demi-God of democratization.

Unfortunately the stated and unstated aims of the series’ curators goes beyond this practical objective. “Spokesperson” Dot Tuer’s catalogue contains much talk about collectivity and community, some mention of the films and considerably more discussion of the programmer’s angst. A typical passage reads: “Aligning myself with Porter’s and McGowan’s motivations, I choose, or collectively agreed upon with the filmmaker, to screen a work by each Funnel member that has been neglected through distribution, shelved through ambivalence, or commissioned for the series. In selecting work in this manner, I become interested not in the validation of particular works as ‘strong’ films but encouraging the members to consider the Funnel as a collective entity which could facilitate the production and distribution of all members’ work.”

A reading of this disclaimer could begin by pointing out Tuer’s jittery attempt to make synonyms of the concepts of alignment, choice and collective agreement. It is an attitude reflected elsewhere in the catalogue’s alternating proclamations of unity and disassociation. As part of their striving for community, the programmers have issued a catalogue that not only reviles individual works but condemns the audience coming to see them. Luc Chalifour’s Reminiscence is “an impeccably crafted, excruciatingly vacuous” work screened only for purposes of comparison to Mike Fitzgerald’s Untitled, “An excruciatingly raw one liner.” Both works are what Tuer calls “classic examples of the layman’s perception of experimental cinema.” But why is the Funnel tormenting the poor layman with such work?

Well, these are works “neglected through distribution.” Yet here too, her phraseology is unintentionally impregnated with a contradictory subject: is there an ominous force actively neglecting the distribution of these films? Or do these films dig the grave of their own neglect when distributed? The same ambiguity pertains to the phrase “shelved through ambivalence.” Even more revealing, though, is Tuer’s equating the “neglected” and “shelved” films with commissioned work. Can we say that within this linking of old and new work there is desire to continue the tradition of abuse? Let us create work that will be ignored so that we may redeem it.

More questionable is the refusal to validate the “strong.” The strong must not appear precisely because they are strong and, thus, apparently, can be of no use to the collective strength of an experimental film community. More insidiously, we are told (at last!) that it is the consideration of the Funnel, not the films, that is central to the entire pursuit. The point of Cache du Cinema is to define the institution that presents it. This is, presumably, a far more worthy goal than using an institution to define a movement.

Nowhere in the series’ literature is there a distinction made between the Funnel filmmakers and the larger numbers of outsiders who are being co-opted to define the Funnel’s role. Nor is there any real explanation of why so many non-Funnel filmmakers whom Tuer acknowledges as having been “recognized through their work” (i.e. having succumbed to “validation”) were not given the opportunity to participate. Tuer’s list of those deliberately ignored – Kay Armatage, Peter Dudar, Betty Ferguson, Phillip Hoffman, Rick Hancox, Patrick Jenkins, Richard Kerr, Keith Lock, Lorne Marin, Peter Mettler and Adrienne Mitchell – is a role call of talent without whom the building of a Toronto film community would be unthinkable. None of these artists suffer from overexposure. Far from detracting from the achievement of younger colleagues, the work of these filmmakers might have provided the sense of continuity and collectivity for which Cache du Cinema was conceived.

What emerges from Cache du Cinema is a rather opportunistically imposed collectivization of people who thought they were “independents.” Typical of Canadian media institutions, the artist was used as testimonial support for the institution that should have been supporting him/her. The institution’s real opinion of the work is apparent in its treatment of the validated few whom it humiliates, the unknown filmmakers whom it reviles and the spectrum of insight it readily dismisses.

Seth Feldman