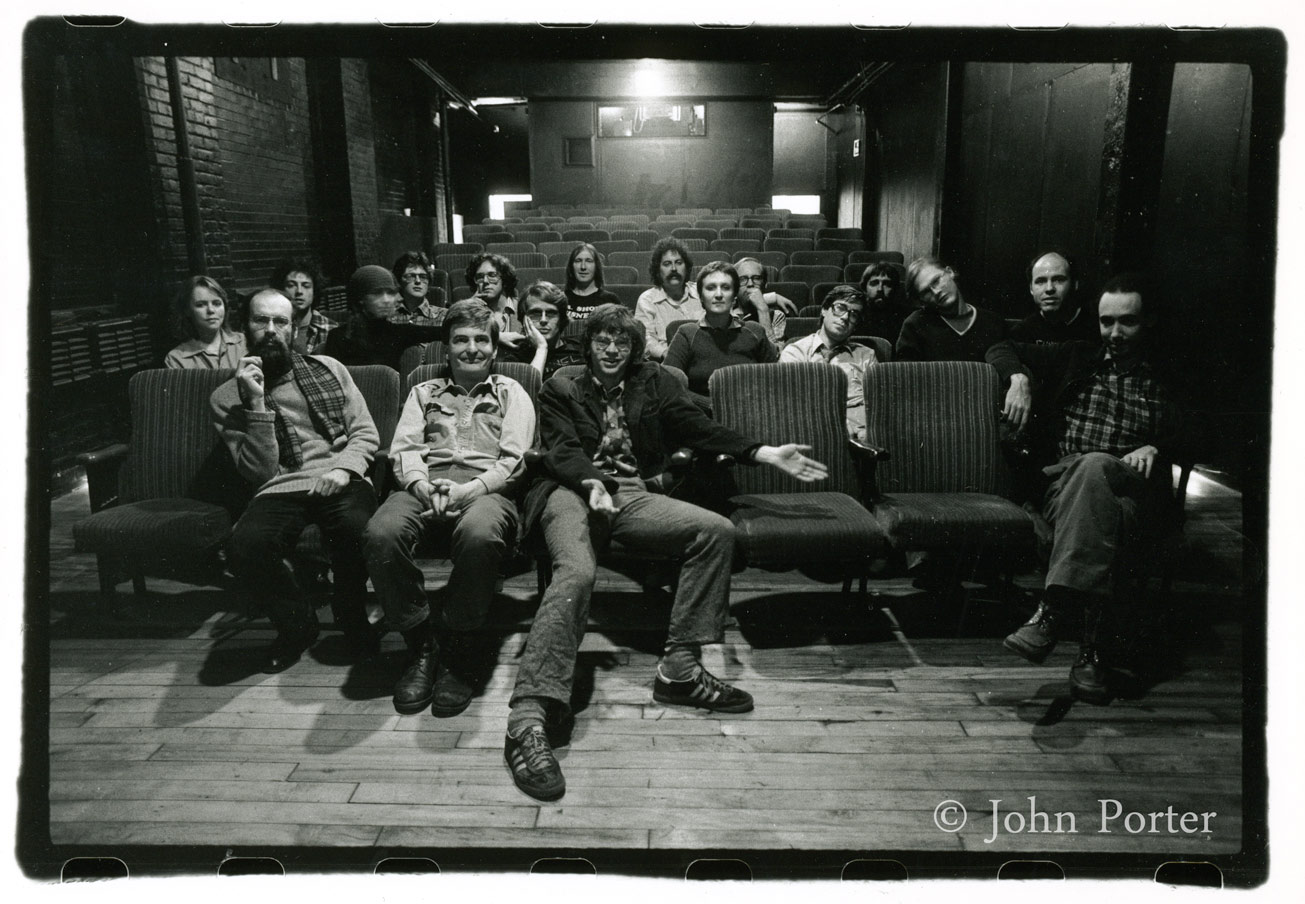

Edie Steiner, David Bennell, Carolyn Wuschke, Ross McLaren, Michaelle McLean, Martha Davis,

David Poole (CFMDC experimental film officer), Mikki Fontana, Jim Anderson.

Photo by John Porter

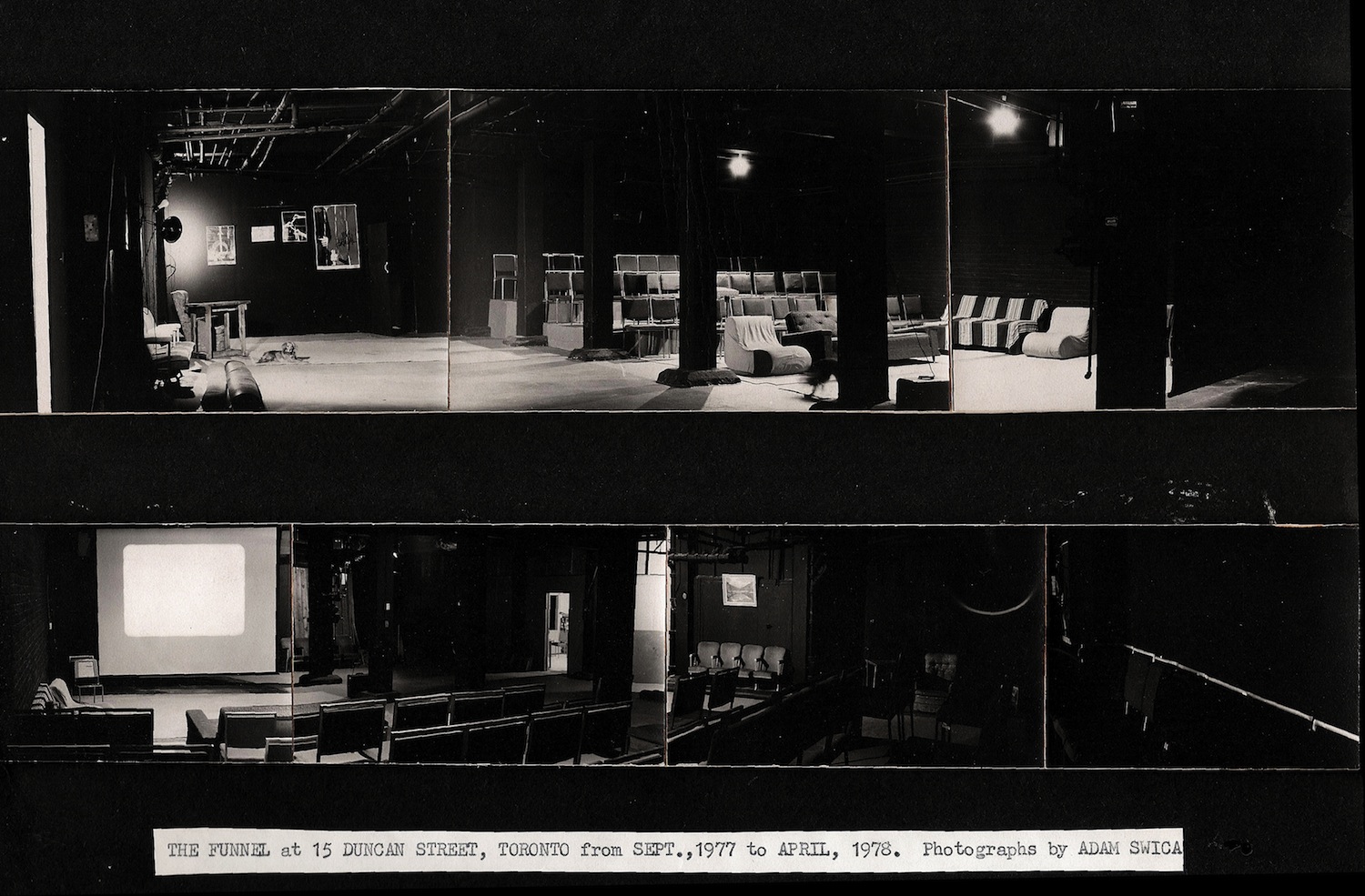

The Funnel by Blaine Allan

This monograph was produced by curator/writer Blaine Allan for a series of Funnel films held at the Kingston National Film Theatre in 1981.

In a single issue of Cinema Canada, published in early 1979, two articles serve as an epitaph for the Toronto Film Makers’ Co-operative, and another, separate article discusses the development of a new centre for independent film in Toronto: the Funnel. While the Co-op had facilitated production of many different types of independent films, the Funnel has devoted its energies to fostering a culture of experimental film.

A skeletal outline of some tendencies of avant-garde film may help establish a context for the Funnel’s work. Experimental film has been characterized on the one hand by a fierce independence and its artists have stressed individuality and autonomy. On the other hand, avant-garde artists film artists have also tied bonds amongst themselves, often in the form of institutions. These bodies stand as alternatives to a common adversary, the system of the conventional narrative film, which dominates cultural notions of what a film is and what it should be. Artists have helped develop networks of distribution, largely cooperative in nature, for experimental film in many different countries. The models for such outlets have been Canyon Cinema in the San Francisco Bay area, and The Film-makers’ Cooperative in New York. Since their establishment in the early 1960s, similar outlets have been formed in Toronto, London, Montreal, and many other filmmaking centres. Moreover, in the United States, exhibition venues for experimental film predated such distribution outlets by a decade or more. Cinema 16 and Art in Cinema were film societies founded in 1947 in New York and San Francisco, respectively. Both have highly regarded histories, though both have also been long defunct. Most importantly, they survived as long as they did through the wits and finances of their founders and the active support of their patrons. The showing were often forced to different locations and irregular times for one reason or another. However, such film societies and their successors formed a necessary part of the cinematic system which determines not only that films be made, but that they can be seen.

In addition, artists have also realized the need to preserve work and have established archival collections. The film produced by conventional means is mass produced in the sense that many prints may be made and exhibited. Whether by design and intent or by the economic necessity felt by the independent artists, his or her film may be more of a unique object. In the first case, the film may in fact not be reproducible. (Villem Teder’s Man Ray Series #3 is an excellent example: the film includes sections of film which is normally used for recording magnetic sound and which is almost totally opaque. The filmmaker resorted to this extreme to achieve a blackness which is unattainable in projecting any photographic film which, however black, transmits some light. In fact, the only way the film could be “reproduced” would be by hand, that is to say, by doing the film over again.) In the second case, the filmmaker may simply not have the means to make multiple prints without a committed buyer or other financial backing.

The experimental film movement has been marked by a holistic vision. Branded by marginality, the experimental film has been forced to expand past aesthetic bounds into institutional alternatives. Film artists have conscientiously taken into consideration the necessity of a programme of distribution and exhibition by which their work can be made accessible and seen. Otherwise, the type of the avant-garde artists — the bohemian starving in a garret, scratching in a garret, scratching out masterpiece after masterpiece, never to be seen as long as the unfortunate wretch breathes — might be true.

Simply because such ventures are generally artist-initiated, it should not be assumed that there is total harmony and agreement in the field of experimental film. In fact, the field has been the site of constant controversy, debate and discussion over curatorial procedures of evaluation and selection on all levels of film production, distribution and exhibition. The Funnel rose out of just such an activist spirit.

In April 1976, Toronto’s first Super 8 Film Festival was mounted through the efforts of the Ontario College of Art’s Photoelectric Arts division and Image 8, a self-described “ad hoc collective of (Super 8) filmmakers.” The same sentiments which had generated Cinema 16 produced this event for Super 8 filmmakers. When Amos Vogel established his film society in 1947, one of the aims was to vindicate a medium, the 16mm camera, which had been relegated to a subordinate position because of its non-professional status. What had been ignored, and the balance which was to be redressed, was the fact of the work being done in the amateur (in both senses of the word) medium. In comparison, in the mid-1970s, Super 8 had made great technological advances over its brief history. More importantly, though, it remained an economically and technologically accessible medium; 16mm, the former home movie format, had advanced in technical sophistication and, not incidentally, in cost. The Toronto Super 8 Festival served as a collecting point for film work and for filmmakers. More a convention or information centre, it bypassed the festival route which involves competition and expert judges. Instead, for exhibition, it embraced broad categories of Super 8 activity: animation, documentary, experimental, dramatic, home movies and commercial, educational, and industrial films. The promise and success of the first Festival, however, was such that increased institutional respectability took over from the enthusiasm that spawned the event. A casualty of this development in the Festival was one of its founders, Ross McLaren.

In 1977, McLaren initiated a series of experimental film screenings with the facilities and space of the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication. While these programmes were associated with CEAC, they were also, to a degree, autonomous. CEAC provided resources and space; McLaren and the nascent Funnel provided the philosophy and activity of regular avant-garde film exhibition in Toronto.

Within a year, early in the organization’s formative period, the Funnel found itself without a location because of a complex of events in mid-1978. The Funnel and CEAC had split on political grounds as CEAC took an inflammatory position of support for Italy’s Red Brigade. At about the same time, CEAC lost government funding which had been essential to its operation. Consequently, it also lost its premises, and the Funnel had to be relocated.

An indication of the organization’s autonomy and vitality, the Funnel was formally incorporated in July 1978, the same month it was displaced from CEAC’s location. Within a matter of a few months, the Funnel’s present location at 507 King Street East, in the shadow of a Don Valley Parkway overpass, was discovered. With members’ volunteer labour, the space was reconstructed to include office and film editing facilities, a gallery, a darkroom, and a theatre, furnished with seats retrieved from one of Toronto’s former movie palaces, the Imperial Theatre.

The Funnel’s subsequent activity has sustained the momentum with which it began and the increased impetus in its “reconstruction.” In fact, it can easily be said that the Funnel has been highly active in serving two groups: the Toronto community in terms of offering access to facilities on a limited basis, and as a regular showcase for experimental film; and the experimental filmmaking community of Canada, for which it has developed a strong voice.

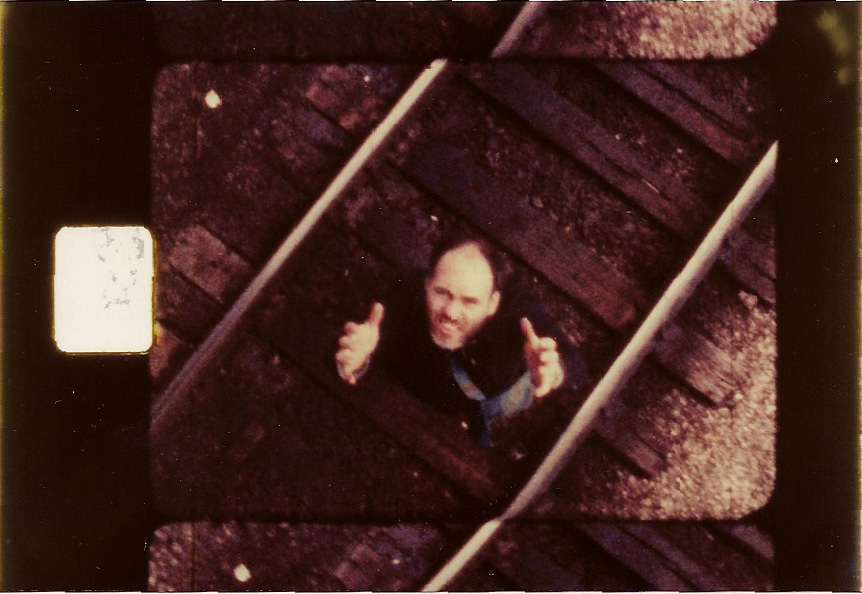

The Funnel first general meeting at 507 King Street East and beginning the projection booth. Photo by John Porter

The theatre offers film programmes of a wide variety at least twice a week. One of the mainstays of the Funnel’s screening policy is the ongoing work of the group’s own members and filmmakers in the vicinity of Toronto. In addition, the theatre also serves as a venue for touring avant-garde film artists to present new work and old. Recent visitors have included such major figures of the United States avant-garde film as Robert Breer, Larry Gottheim, and Ernie Gehr, and the British filmmaker/writer Peter Gidal. In addition, the Funnel has also served as an exchange body, showing Toronto filmmakers’ work elsewhere. One such exchange involved two evenings of Funnel films in Chicago and, in return, two programmes of independent films by their counterpart, Chicago Filmmakers. (By my reckoning, the Toronto shows of Chicago films were much better attended than were the Toronto films in Chicago, which I take to be less an indication of the worth of the Funnel’s films than of the Toronto avant-garde film community’s enthusiasm). Perhaps a more important such exchange was, in October 1980, between Ontario and Quebec experimental filmmakers, traversing a border which is often more difficult to cross.

Many Funnel programes and activities are as much educational as entrepreneurial. In terms of screenings, the theatre reflects the tradition of avant-garde film, precursors and examples from the past, as well as the work of the present. Moreover, lecturers at the Funnel have included P. Adams Sitney, the preeminent historian of the United States avant-garde film, and film and video maker Taka Iimura, who conducted a ten-week series of screenings and lecture/workshops on the development of formal cinema.

However, the Funnel’s personnel are, for the most part, filmmakers, and much of the organization revolves around facilitating new films and new film forms. To this end, the Funnel offers series of workshops on different aspects of filmmaking, from the fundamentals to more sophisticated processes. McLaren, who also teaches filmmaking at the Ontario College of Art, stresses a demystifying approach to film production for his students. While film may indeed be complex, it can also be reduced to a few rudimentary elements and made more comprehensible. At the same time, these basic aspects of the film material can be played with and manipulated, and the medium made, in a truer sense, “experimental.”

front row: Dave Anderson, David Bennell, Jim Anderson, Patrick Jenkins

second row: Michaelle McLean, Anna Gronau, Frieder Hocheim, Suzanne Naughton, Bruce Elder, Peter Chapman, John Porter

third row: Paul McGowan, Ross McLaren, Stephen Niblock, Tom Urquhart, Jim Murphy, Villem Teder, Adam Swica.

Photo by John Porter

The Funnel is a cooperative, its active membership comprised of fewer than 30 people who are wholly responsible for its policy, programming and operations. A group statement asserts, “Members are committed to certain shared aesthetic ideals, and to this end they contribute financial support (in the form of a membership fee), and time and labour.” The “aesthetic ideals,” which support the organization can be quite loosely defined in such a term as “innovation,” a word which appears quite frequently in statements about the Funnel’s work. However, in terms of a group activity, the organization serves as an “alternative” to a dominant form or body of work. In this sense, the establishment of the Funnel itself is only a first step, or a small part of a larger cultural movement.

The Funnel, as a body of independent filmmakers working collectively for the benefit of a particular mode of filmmaking, is as much an expression of cultural ideals as an expression of a collective aesthetic. Such an ethic of cultural response, however, has problems particular to Canada. The Funnel’s type of cinema cannot adequately be characterized as independent, that is, in terms of financial support. In the United States, the independent film in the formative 1950s could be set in contrast and opposition to the seemingly monolithic Hollywood feature film industry. Such a formidable adversary permitted (or necessitated) a solidarity amongst different types of films. For example, a meeting of the New American Cinema Group – which indirectly led to the formation of such influential bodies as the Film-maker’s Cooperative in New York – included producers, distributors, and makers of narrative, documentary, and experimental films. By participating in such an activity at the time in that context, they were all in the avant-garde, or at least in the vanguard. Canada has no Hollywood, although the National Film Board and the CBC are often suitable surrogates as adversary figures. Most films of all types are, in some sense, independently produced. Hence, independent film production covers a broad spectrum of film forms. Experimental filmmaking, however, has become even more marginalized in the field of independent cinema. In reaction to the situation, the Funnel has helped form an alliance, the Association of Canadian Film Artists, to act as a collective voice of experimental filmmakers. Writing on behalf of the Association, Funnel filmmaker Anna Gronau argues, “The needs and concerns of this group (experimental filmmakers in Canada) have not been properly represented at various national conferences of independent filmmakers… There is a need for a single national voice, rather than many regional ones; galleries need to be made aware of current work; better distribution, exhibition, and criticism are needed in Canada. Film is internationally ghettoized as a second-class art form and action must be taken to change this.

This certainly is a more strident tone for the Funnel and for Canadian experimental film. However, it is necessarily stronger, more reactive, in that the Funnel struggles on the cinematic front, against policies which favour independent but non-innovative film production, and also the artistic front, as both gallery and film theatre. If film is “ghettoized as a second-class art form,” then experimental film is shunted firmly to the margins of that ghetto. The artist, filmmaker, or group, constantly discovers the contradictions in establishing a voice of dissent while opposing policies of organization planted firmly in the cultural ground, the artists compelled at the same time to court the favour of these bodies precisely on account of their privileged positions. Perhaps the most concise and representative example I can cite involves the Funnel’s gallery and not its theatre. A recent installation in the gallery was reviewed by a Toronto daily newspaper – thus made much more public – three weeks after the opening of the exhibition and a matter of days before the work was to be removed. While one might be thankful for the useful publicity, one can also only be frustrated by the bad timing. In relation to film, the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival has changed philosophy and practice such that, in 1979, the Funnel loudly criticized the event. Contradictorily, possibly demonstrating a lapse in solidarity, yet in a strangely subversive turn of events, the Festival’s major prize was won by Funnel filmmaker Patrick Jenkins for his film Fluster. This relationship, however, can readily and deceptively be incorporated into an historical/aesthetic perspective on the avant-garde film. A recent pamphlet attempts to update P. Adams Sitney’s argument that the experimental film is characterized by a “radical otherness in relation to mainstream or commercial film” by adding that film activity has resulted in a “more modest definition of the differences between commercial and independent film, which no longer has an “other” to sustain it, and arguing further the experimental film’s marginal status. A truer assessment, however, must take into account the experimental film’s double front, its antagonistic relationship to both commercial film and to naturalized values of art and culture. In these senses, the Funnel and alternative galleries and exhibition places find themselves under a cultural hegemony, a relation of domination in which the dominant structure is assailable, but also constantly shifting and able to incorporate, co-opt, or naturalize what might at one point have been radical. One of the Funnel’s tasks as an alternative, as a “radical other,” in its filmmaking, its education, and its agitation, it to work towards an ongoing assessment of such a cultural situation and how, for experimental film, it can be improved.

II.

“The thing that’s important to know is that you never know. You’re always sort of feeling your way.” Diane Arbus

A definitive analysis of the Funnel’s film seems both difficult and unwise. There are several reasons for such a prohibition. One is certainly the youth of the Funnel as a filmmaking body and as an organization. On one level, the establishment and maintenance of the cooperative and its activities have undoubtedly sapped a degree of the energies and time of the filmmakers who run it. On another, related level, the filmmakers’ output as members of the Funnel is limited compared to their output prior to its incorporation. The membership of the Funnel includes such filmmakers as Michael Snow, Jim Anderson, Bruce Elder and Dave Anderson, who had been well known in Canadian alternative film culture for several years, and others whose first films were made near or within the lifetime of the theatre. This raises the question of how one considers their “pre-Funnel” work. In turn, this leads to problems of the critical terms within which such group work is to be read. In particular, the issues are influence on the one hand and common ideals or preoccupations on the other. Both are pertinent, although the former seems a question for the future and the latter seems a route for a provisional analysis.

A second reason blocking a definitive, collective analysis is inherent in the design of the collective itself. The Funnel is collective in terms of organization, but not necessarily in filmmaking practice. Other collective media producers, such as Kartemquin Films, Newsreel, Intermedia, or Videofreex, have produced group-made projects, often signed to reflect collectivity rather than divided labour or individual artistry. Thus far, Funnel projects are the works of individuals. When I refer to “influence,” I mean particularly the interchange of ideas and insight amongst members of the group. From its start – even back to the Super 8 Film Festival precursor – the Funnel has given a home to this kind of information exchange, which encourages a structure of influence to inform members’ works. The products of this energy have, however, just begun. A consciousness of tradition, specifically the traditions of the international avant-garde film, involves a different kind of influence. Furthermore, it also entails the spirit of innovation, development of the past, which the Funnel stresses in all aspects of its activity.

The work of the Funnel generally evolves from 1960s and 1970s structural film, using that form’s emphasis on the nature of the image, the materials which constitute the medium, and the resultant, implicit critique of the representational system of the cinema. In addition, the films of the Funnel often direct attention onto the realm of personal experience. considering the fact that the home movie mode or the ethnographic film privilege the representational, the combination of these two ethics in one, diversified, body of film is at once ironic and distinctive. However, film raises the double-edged quality of personal experience as it relates to the generating or discussion of works of art. Artworks can be seen as mediating experience. “Mediation” serves a more precise purpose than “expression,” in that it implies the impact of art on experience as well as that of experience on art.

The double direction of this formula comes out in this notion of mediation. However, it is also prevalent in the attention the films give to daily experience, the conscious use of film material – the legacy of 1960s avant-garde film – and perhaps most of all, the experience of being a filmmaker. In an interview, Anna Gronau finds the point one worth stressing; “What we do is not ‘films by artists’ – we are filmmakers.” In several films, the filmmaker turns the camera on him or herself – John Porter in Cinefuge; Ross McLaren in I.E.; Anna Gronau in In-Camera Sessions; Villem Teder in Filmmaker Packing and Unpacking his Bags. In each case, significantly, the film treats the medium unconventionally, stretching its technical and technological boundaries. this raises a related issue which runs through Funnel films, that is a sense of play. I do not mean to imply that the filmmakers are not serious about what they do. However, part of the personal experience of being a filmmaker entails the sheer fascination for the medium’s many secrets and its multi-faceted potential. Many of these elements are, however, bound by conventions of narrative or documentary films. Conventions are the tacit agreements between artist and spectator by which the artwork is made comprehensible, and should be thought of as culturally determined and not a matter of personal limitations to understanding. By acknowledging that these conventions do exist in the dominant, narrative film, one method of exploring the medium involves simply playing with the elements which are considered comprehensible or acceptable. For a theatrical, narrative film, a shot with abnormal exposure – whether overexposed and bleached out or underexposed and dark – may be rejected as unacceptable. The assumption here is that the profilmic event can be reconstructed, that the shot can be done again. In a documentary film, such a shot may be retained if the event it records is important enough to the film as a whole. This time, the filmmaker and spectator “know” that the event was unique and cannot be repeated. What both cases ignore is the fact that such violations of convention may uncover patterns which may otherwise have gone unnoticed, or associations which may not have been made, suppressed by conventional agreements, the contract or propriety or order.

Play, in this case, can be read as the means by which order is disrupted and unity fragmented.

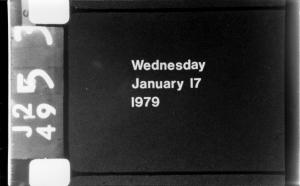

This general principle is addressed in several modes. In Michaelle McLean’s (sign for a square here), a perfect square – a constructed plane – is broken down into its four linear constituents through the selection and motion of the camera. Ross McLaren’s Wednesday, January 17, 1979, through the most minimal imagery, film-specific icons (sync marks, exposure flare), and a series of titles, addresses the unifying regularity of time and our expectations of time. Frieder Hochheim’s Accumulative Distinctions Extending a False Utility ( a title which invokes this very issue of the constituent and discrete units of something considered to be a unity) uses conventions of off-screen space in an ironic way to place the problem on the complex level of narrative. Adam Swica’s Montana Shuffle stresses its own formal principle of unity, the vertical line. By “finding” such lines in the environment and “placing” them in exactly the same location in the frame, the film also indicates an awareness of the principles of selection and combination which underlie discursive systems. The film does not simply order the forms; it is also about the principles of that ordering process.

An indication of these concerns with play, order, and disorder, can be found in two of the Funnel’s most nearly expository or documentary films. both Suzanne Naughton’s Mondo Punk and Ross McLaren’s Crash ‘n’ Burn concentrate on artifacts and performance of punk culture. In fact, they can be read as documents of Toronto’s vital punk scene of a few years ago. Rather than unifying the events, making them cohere, both films threaten to fly apart in terms of structure. Both are bound together by the music. Naughton’s visuals are a manic montage of punk people and events. McLaren’s are located in a single concert setting. Recorded non-synchronously, the image sand sound come together only sporadically and, evidently, by accident; instead of a conventional unity to be assumed, the coincidence of sound and image becomes something more like a collision. Moreover, the collision is realized not just in the film, but in the sound/image connections made by the spectator.

The confrontation between personal experience and the film material becomes more explicit when the presence of the filmmaker is inferred. Anna Gronau has written of Dave Anderson’s Bi-Rite as a “window film,” a subgenre into which her own Maple Leaf Understory may be placed. Both films gaze through windows. The duration of the gaze reflects an interest which implies the consciousness of the person looking (just as the word “duration” implies the experience of time and not the more abstract ordering system). However, the image is treated to generate an interest not only in what is seem through the window, but how it is seen, the differing qualities of light and, consequently, colour rendered at different times of day, in different conditions, and, doubling the complexity, by the different mechanisms of camera and film.

The Diane Arbus statement, quoted by Patrick Jenkins for a programme of his films at the Funnel, implies artwork which admits to its own uncertainty or provisional status. Traditionally, the artwork is seen as complete. Uncompleted works are read with an implicit allowance for “what might have been.” Provisional works are often subordinated as sketches, cartoons, models, or rehearsals for larger, finished and polished products. However, the statement also supports an ethic of innovation by way of experimentation or, in the sense I have sketched in, play. “Feeling one’s way” implies the complexity of a closed maze or the darkness of a corridor through which one is compelled to pass. The opportunities to feel one’s way exist because of the “play,” in a different, related sense, of the medium and of the situations. Stretching the medium’s potential and conventions, the provisional, step-by-step results of such progress, leads on to further experimentation and continued activity. The Funnel thrives on such ongoing activity.

Film Programme

Kingston Artists Association

National Film Theatre, Kingston, February 27-28, 1981

Wedding Before Me (Patrick Jenkins, 1976) The basic footage was shot by my Uncle John in 1953 of my parents’ wedding and hence the original footage was shot before I was born. I optically printed the original footage onto Super 8 and recorded the impression and ideas that I had via repetition and other alterations.

Fluster (Patrick Jenkins, 1978)…deals with a state of mind where thoughts, images and emotions rush us at in a wild and uncontrollable manner. At this point we cannot grab onto any distinct thought, image or emotion, because we are confused by a chaos of mental impressions. It is probably the most blatantly abrasive and aggressive film that I have made.

Ruse (Patrick Jenkins, 1979) Ruse is an intense, poetic film. It was shot over a period of four months in the filmmaker’s house in Toronto. The main image in the film is light penetrating through glass windows, Venetian blinds and glancing off objects. However Ruse is not intended as a mere documentation of light. It is also about Jenkins’ reaction to his home and illustrates his feelings that in some ways the world is an immensely deceptive and illusory place to live.

A Sense of Spatial Organization (Patrick Jenkins, 1980)

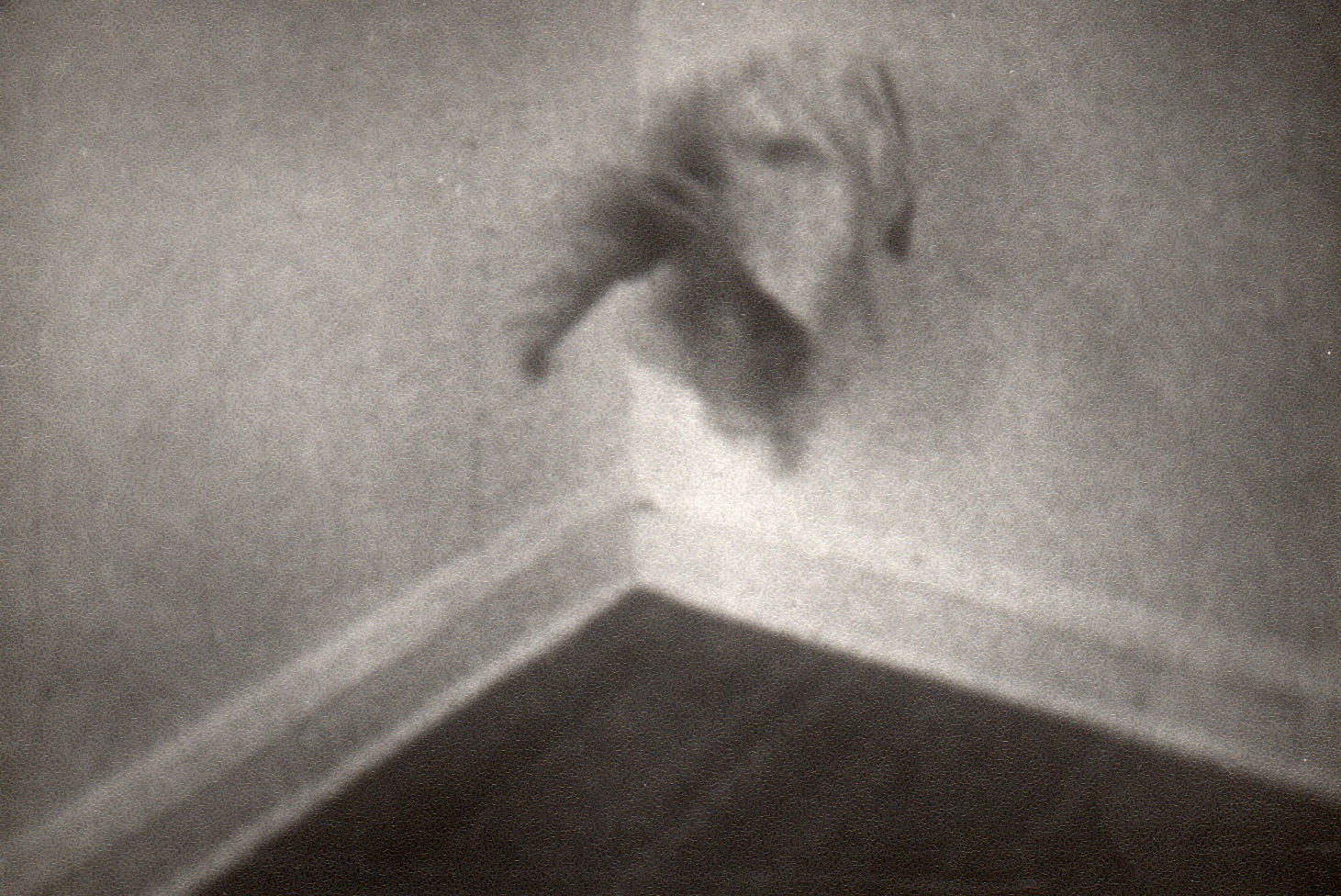

Morning Bed – X (Michaelle McLean, 1979) The film consists of a series of images sandwiched between two shots of an unmade bed. The film came together very quickly from some “outs.” I liked the way they looked together and shot the bed “sandwich” to act as a container for them.

20:20 (Michaelle McLean, 1980) Twenty minutes of late afternoon light shot at one minute intervals of one second each (18 frames). The image is a window with a sheet tacked over most of it. The sheet acts as a screen upon which the shadow of the window’s cross-pieces is projected. Projecting the film on a screen echoes the image and its production.

Untitled (Square) (Michaelle McLean, 1980) I taped a square out on a parking lot and filmed it. The butting together of different “real-time” events is one of the qualities of film that sets it apart from painting or sculpture. It was this quality I was interested in. By changing the sequence and rhythm of the information given I was able to manipulate the temporal experience of the shape.

Weather Building (Ross McLaren, 1976) “The flashing weather beacon on a Toronto building is the structurally fixed point in this precise composition of illuminated surfaces and positive/negative imagery. Noting the ‘intuitive process’ of the film’s first half – which was shot on Super 8 and edited in-camera – McLaren analyses and ritualizes the visual information through a video playback that echoes and doubles the original, improvised ‘score.’ Tightly framed with a menacing soundtrack, Weather Building generates a claustrophobia and paranoia that loosely suggest the violence and boredom of punk.” Ian Birnie, The Art of Gallery of Ontario

I.E. (Ross McLaren, 1976) I.E. is composed of a series of themes and variations involving the interaction of camera and filmmaker. There is a predominance of in-camera animation, and the resultant distortions and manipulations both reveal and conceal the process of the film’s making. I.E. deals with illusion, although there is no doubt that it verges on the autobiographical. What we see is the filmmaker in the act of making the film, that is, we see the traces of this process, insofar as the procedures used are capable of transmitting them. The figures in the film finally lose their abstract value and become vehicles for the rhythmic, lyrical flow of imagery.

Wednesday, January 17, 1979 (Ross McLaren, 1979) This film deals with the problems of revealing “the truth” in a film. It explores cinematic traditions regarding the passing of time and the portrayal of history. Since film is in itself a temporal medium, the questions regarding its manipulation to achieve this end are revealed. The film demands an examination of film as a narrative medium versus film as a physical entity responding to a given technology.

Maple Leaf Understory (Anna Gronau, 1978) I was interested in film as a light gatherer and strainer. Various planar surfaces act as an analogy to the filmic process. The film is composed mostly of short structural manipulations – occurring like thought impulses – often too quick to become really conscious. So the film, camera, and so on, parallel the process of perception as a plane between outer reality and inner reality (consciousness).

In-Camera Sessions (Anna Gronau, 1979) This film deals with conventions, assumptions and properties of editing/choice-making. It is an inside look at the art-making process. At the very outset the central character/filmmaker reads a statement: “Whoever has their finger on the trigger makes the decisions,” and then about midway reads a quote from Clement Greenberg: “The tendency is to assume that the representational as such is superior to the non-representational as such.” These are clues to the question of who really makes the decisions.

Accumulative Distinctions Extending a False Utility (Frieder Hochheim, 1977) An anxiety play which presents a situation, a confrontation with the absurd. This drama of sorts, as in the Absurd Theatre, questions not what will become of this situation, rather, what in fact IS the situation?

Cinefuge (John Porter, 1979) Many of my films, and especially this one, was influenced by Sergio Leone’s scene in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly when Eli Wallach runs full speed around the camera while it follows him. There is something about spinning movements and blurringly fast movements which move me when I see them. I swung a cheap, small camera around me on the end of a 12 foot fish line, while I stood on the spot. The line was attached to the front of the camera so it would always be aimed at me. By following the camera I could appear stationary. By standing still I could appear to be spinning. I consider this film to be a dance so I got a professional dancer – Judy Miller – as a partner. Her role was much more difficult than mine. She had to run around me as fast as possible and she had to enter and leave the perimeter of action without colliding with the camera or the line.

Down On Me (John Porter, 1980) John dances with, and is led by, the camera, which is running at one frame per second and turning its own way on the end of a fishing pole line while being raised and lowered from rooftops and bridges. Throughout, the camera is looking down at John on the ground, who’s looking back up at the camera and turning with it.

Moving Bicycle Picture (Jim Anderson, 1978) In the summer of 1972, I had the happy idea to go on a bicycle trip from Toronto to Thunder Bay, Ontario. I took along my Keystone 16mm camera and this film shows the results, but not all. That is to say I leave out important events like eating and camping and concentrate mainly on what is seen from the moving bicycle. After a time the camera, bicycle and myself become entangled, involved friends and enemies. At the same time the film examines itself in terms of its own nature – that is to say, image, frame, etc.

1-51 (Peter Chapman, 1977) A shot taken from a documentary film was contact printed, the print was printed again, that print was printed and so on… fifty-one times. At that time I was heavily influenced by the gradual process music of Steve Reich and the film, with its slow changes in appearance, strikes what affinities it can with that approach. We watch a film “move from concentrate to abstract.” It is a look at the fiction of repetition.

Montana Shuffle (Adam Swica, 1976) Film in the form of a card shuffle, with images slipping into a slot determined by the artist.

Filmmaker Packing and Unpacking His Bags (Villem Teder, 1980)

Man Ray Series, #3 (Villem Teder, 1979) “Ray-o-grams,” recordings of shadows of pieces of film; shadows produces by the light of the exposure, as well as shadows produced by the strips of film being in contact with each other during processing. From the initial results in black and white, a short length was edited and cut into a loop. With a printer, 3 exposures of the loop were made onto 7381, each exposure using one of the 3 primary colours (cyan, magenta, and yellow). For each exposure, the ratio of original to copies was varied, as well as the loop running in different directions and the image being reversed left to right sometimes in the resulting film, bits of the black and white were cut into short sequences, to act as an introduction for each movement. Fragments of the colour images were selected and intercut with mag film to heighten the effect of afterimages when cutting to black.

Produced with the assistance of the Canada Council.