Start ups and Show Downs: an interview with Anna Gronau (2013)

Mike: The first film co-op you were involved with was the Toronto Filmmaker’s Co-op, the fabled anarchist haven that issued smoke signals from Rochdale College.

Anna: I remember, as a young art student, venturing to attend a few Co-op meetings during its heyday at Rochdale. I went with Leslie Padorr to a workshop for women in how to use one of the Co-op’s dauntingly (to me) heavy-looking 16mm cameras. The meeting had a very radical feminist tone to it. The idea was a kind of Newsreel interventionist cinema, that women could document things happening in their communities. Leslie’s daughter, Mona, was in the Campus Co-op Daycare, and the University was threatening to close it, so an occupation by parents was being undertaken to prevent the closure. I don’t know if a film was ever made about that, but I think it was discussed. But then, at another meeting I went to, someone said their goal was to make Monty Python style comedies. There were wildly different ideals being expressed, yet they were able to co-exist because we were all young, poor, pretty much aspiring, but not yet achieving. What we had in common was greater than our differences.

Mike: A few short years later you were part of the group that presided over the end of the Co-op, it had been taken over by big spenders with starlight in their eyes.

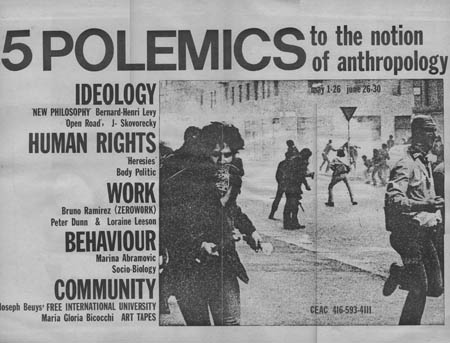

Anna: As you know, we — a few future Funnelites — were trying to save the Filmmakers’ Co-op (and make it a future institutional home for the Funnel). We had a number of meetings there for that purpose, and then, of course, to deal with its horrific financial situation and initiate bankruptcy procedures. Once it was clear that the Co-op had no choice but to declare bankruptcy, the issue arose of whether its funding would continue to exist and be applied to another organization (yes please!) or just get absorbed back into the overall pot. It was either Jim Murphy or Bruce Elder who spoke to the Canada Council and its position was that we had to be very clear that we were neither the continuation of CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication) (heaven forbid!) or the rebirth of the Co-op (it was illegal to declare bankruptcy and then change your name and do exactly the same business). I think they asked very specifically for a letter that stated we didn’t support CEAC. Probably, by that time, they had received word from other arts organizations declaring as much, but nothing yet from the Funnel. We discussed the whole issue of what to do about the Council’s request/demand. It was definitely a quandary. I think we were all somewhat torn, because it would be a betrayal of CEAC. On the other hand, CEAC seemed to be bent on self-destruction, and their public advocacy of violence was pretty ugly. At that point, I don’t think we actually reached a decision. Some time around then, the idea of taking this to ‘the community’ was put forward. Jim Murphy, being the most sophisticated, may have been the one to come up with that, or maybe it was something that actually came from the Canada Council itself. I think that inner conflict was there even way back then: we were hungry for that whatever could be salvaged from the Co-op and annoyed at CEAC for throwing away a good thing, especially when we were in transition anyway. I think we also felt that the rest of the art community had already bailed on CEAC and we’d be just committing institutional infanticide by killing off the fledgling Funnel through a noble gesture that had no chance of eliciting solidarity or saving CEAC. But I believe we felt pretty guilty about the whole thing and relieved when the guilt got spread around by a vote that gave us what we had wanted. The situation wasn’t simple, by any means, and maybe that ‘dance’ you saw was an awkward expression of its complex, and apparently, for Ross, uncomfortably unresolved nature.”

Mike: When CEAC (Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication) came under fire for (allegedly) supporting the Red Brigades, the Marxist-Leninist paramilitary Italian group, they made the rounds of their community, asking for letters of support, and naturally turned to their experimental film spawn downstairs. This was a pivotal moment in the history of the Funnel. It had been run as an ad hoc group centered around Ross McLaren, but now, for the first time, a community meeting was called to which 20-30 people showed up. Most felt expressing support might threaten the fledgling organization, and smear them with the charge of terrorism. John Porter suggested that the letter state simply that CEAC had been helpful to the Funnel by providing space and facilities, but even this was deemed too much. People voted to become a separate organization, and to apply for arts council fundings. In the meantime everybody would chip in a $100 membership fee that would secure a lease for the new space.

Anna: I remember that meeting. Ross was there and probably did ‘call’ it. It’s a very good bet that Jim Murphy was the one who told us we should organize it. Jim was from New York City and had a really great political and strategic sense. In the early ’70s, draft resisters brought a huge injection of energy to the city, particularly in the cultural area. Jim was either involved with or very familiar with the Filmmakers’ Co-op in New York, and that experience was likely a huge contributor to the development of the Co-op and Distribution Centre in Toronto. We, on the other hand, were naive kids. I think I was about twenty-five, Ross was twenty-four. I was involved in the run-up to the meeting, and helped with some of the organizing and invited people. Ross was sort of the person that things revolved around.

Ross had a lot of drive to make things happen, but also, his convictions were uncompromising and often unforgiving. There wasn’t much room for agreeing to disagree on philosophical matters. This may have helped produce the Funnel’s distinct ‘identity,’ but it was also a fatal flaw, a kind of Achilles’ heel – the weakness inherent in a strength – that led to people eventually drifting or feeling driven away. There was also some background to that. Ross told me that he had started the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival when he was a student at OCA, but that Richard and Sheila Hill had ‘stolen’ it from him. I never knew the full story of what happened, but it seems Ross felt the Funnel could also be stolen from him.

Mike: So that “fatal flaw” hadn’t made an appearance yet?

Anna: In the early days, I think I was probably the one who moderated any sense, at least among the powers-that-be, that the Funnel was oppositional and nothing more, and convinced them that it had a strong administrative basis. I did the bookkeeping, for example, and reporting for grant proposals. I had my own artistic vision, too, but when we started I was the manager, not the director. My own creative expression and ideas for the organization’s direction came later, when I was director/programmer, and when all the censorship stuff started to happen.

Mike: How did things progress after the Funnel got the go-ahead from that public meeting? How did the people who attended the meeting participate with the start up?

Anna: Some of the people at that first meeting included Tom Urquhart, who I think was at CFMDC at that point, and who helped tremendously with the logistics of moving out of CEAC and setting up the new space. Jim Murphy had been involved with both CFMDC and the Toronto Film Co-op, and as I mentioned before was very important in transitioning the demise of the Co-op and keeping the Funnel from going down the tubes along with either CEAC or the Co-op. He also managed to find the actual theatre seats that we bought from some defunct theatre, which we reupholstered and installed. Unfortunately, Jim is now deceased. He was a wonderful, highly intelligent guy – really quite brilliant, actually. I met him when we lived in a communal house (125 Roxborough Street West — I still remember the address!) along with Jim Anderson and Keith Lock and a guy named Stuart Rosenberg in the 60s/early 70s. Most of the people in that house were part of the Co-op in its earliest days.

I think I had also invited Michaelle McLean to that meeting. (Years later, she became the director/programmer of the Funnel after me.) My idea, as a visual artist, at that point, was to try to build a place where film art and other forms of visual art would co-exist and be shown together, and I think it was on that basis that I persuaded Michaelle to be involved. I don’t recall if Jim and Dave Anderson were at that meeting, but I know that the Andersons were quite involved in the very early days of the Funnel. Freider Hochheim and Suzanne Naughton, who were Ryerson students, also got involved around that time and may have been at that meeting. Their teacher Bruce Elder was very supportive of the idea of setting up the Funnel, but wasn’t involved much in the nitty gritty of building walls, installing seats, etc.

Mike: Do you see a connection between the back-to-the-land experiments of Buck Lake and the Funnel?

Anna: I can see lots of connections between Buck Lake and the Funnel, not just the whole building-the-barn/building-the-theatre connection. I lived at Buck Lake for maybe four or five years, but the barn building, which Keith portrayed in his film about the place, happened over the period of only about a year.Both endeavours – Buck Lake and the Funnel – were utopian projects based on a belief in the strength of the collective. Both were extreme visions of a culture that could operate somewhat outside of the mainstream. I was among many at the time who subscribed to a belief in a cultural/political/spiritual avant-garde that would live, rather than simply espouse, change.

And yes, people from Buck Lake ended up at the Funnel. There was Jim Anderson and Jim’s brother, Dave Anderson, was also at Buck Lake a lot, as well as being a ‘core member’ of the Funnel. Michaelle McLean also spent a lot of time at the Funnel with me. Once Michaelle and I were there alone for about a week in the winter. The chain saw broke and we couldn’t figure out how to fix it. The only way we could cut wood to stay warm and to cook was by using a rusty old swede saw. We managed to make it go through the logs by smearing it with a bar of soap on both sides, again and again. We spent most of the day either taking care of the animals in the barn or cutting wood or cooking. One evening, as we were finishing chores by lantern light, in the dark, we saw this brilliant light shining through the trees off in the distance in the direction of the old logging road. We were terrified that it might be some snowmobilers sneaking up on us: two women alone, miles from anywhere, no phone, no protection. I don’t know if we still had a shotgun at Buck Lake, but I doubt either of us would have known how to use one anyway. We went into the house to re-group. We came out again a minute or two later to see if the light had moved at all. It had gotten higher, it was the full moon! Michaelle and I still have insane adventures together, but that was the one where we both took up smoking.

On a personal level, it would be disingenuous to disregard my relationship with the ‘alpha male’ in both cases. But in my memory, I am well aware of the extent of my own creative input and influence at the Funnel, as well as at Buck Lake. Both Buck Lake and the Funnel were focused on alternate technologies — at the Funnel, it was low-cost/no-cost filmmaking, while at Buck Lake we were exploring older technologies that were able to operate off the grid.

When I was talking to Keith (Lock), he mentioned that the Funnel was an ‘outlaw’ organization. I think he meant not only our fight against the powers-that-were, but our positioning of ourselves against mainstream culture. There were lots of ways in which Buck Lake was also an ‘outlaw’ organization. I’ll tell you about some of those, some day.

Mike: Keith’s partner, Leslie, had a child who lived for a time at Buck Lake. Were there other kids? Was the idea to make this a multi-generational project?

Anna: While I was at Buck Lake no other people there had any kids. I think our generation in general was less prolific kid-wise than previous or succeeding generations… there was the idea coming from the past that you couldn’t be an artist and a mother at the same time, plus the idea that domesticity was oppression. I think we were doubly discouraged from considering parenthood.

Mike: Can you talk about working at the Funnel, both as an office manager and as director/programmer.

Anna: I was hired initially as office manager and I think I did that for about two years, before I became Director. As I recall, we made an application to the Canada Council — at their invitation, actually. As I mentioned, there were a number of us who were around when the Filmmakers’ Co-op folded, and I think the Council liked the fact that we were separate from CEAC, and at least in the same medium (film, I mean) as the Co-op, so they could re-allocate some of their budget to us and they told us we should apply.

One of the things our initial Funnel group decided on was that we would need to have someone to do office stuff. At the time, I was working as an office manager at Arts’ Sake, a kind of impromptu art school that was run by (mostly) painters from the New School/Three Schools — Dennis Burton, Graham Coughtry, Gordon Rayner, Robert Markle, et al. When my job was axed to save money, I was hired by the new Funnel board because I had experience, and had an interest in experimental film. Ross and I had just started dating around that time and discussed the idea of working together. It seemed like a good solution for everyone, so the board approved my hiring.

As far as me becoming the Director/Programmer, the two contributing factors were that Ross didn’t want to be programmer any longer and that I obviously had more experience than anyone else with how the place was run — especially with budget-related things and grant applications. I also had a background in the arts and by then I was getting to know a lot more about experimental film. I probably seemed like the best candidate. I don’t remember if the board looked for anyone else or not. I don’t think so, though. Again, I’m sure that Ross and I both thought it was a good idea.

I don’t think Ross ever really wanted to run a theatre. Our focus on exhibition was endorsed by the funders because a) that was a big part of what we had done with CEAC (although The Funnel also had filmmaking equipment there) and b) our being exhibitors meant that we weren’t seen as the Filmmakers’ Co-op disguised to evade creditors. We were probably told that it was essential for us to be an exhibitor first and an equipment centre second. Anyway, I do remember Ross saying that his interest lay more in the equipment access part of the operation. He was teaching at the time and what with that plus all the work at the Funnel, he wasn’t getting much time to do his own work. I may be wrong, but I think Ross stayed on as president of the board and equipment manager. (And that’s when Michaelle became office manager.)

The equipment managers we had were also really important: Villem Teder was followed by Midi Onodera, and both of them were incredibly creative and helpful, getting filmmakers going with the tools they needed, holding workshops, supplying the theatre with the best equipment possible, etc. In lots of ways, they were really the people who made that community come alive: seeing films by local and international filmmakers was important, but the real artistic and social expression that defined us came from people getting their hands on cameras and making work.

Mike: How was programming organized?

Anna: There was never any problem finding work to show. For international shows we sometimes used a fabulous publication called The Film and Video Makers’ Travel Sheet. It was published on a regular basis by the film department of the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. It was a clearing house for artists and exhibitors to find each other. There was a real circuit in those days. The only way you could get your film shown was by travelling with it, so you’d post an announcement that you had a new film and wanted to go on the road. Exhibitors would also post information about their programming. So we used that quite often. After a while we got a good reputation and received lots of requests for shows. There were many more than we could possibly have ever shown, and we were having screenings at least two evenings per week!

We got many submissions from Canadian filmmakers and we did our best to show their work. There was no quota, but it was a priority. I don’t recall if there was any stipulation from funders that we should do that, but it wouldn’t seem odd if there had been. Even if there was a rule about it, I’m pretty sure we would have tried to show local and Canadian work anyway — it was in our best interests as filmmakers, after all, to build a profile for homegrown talent.

We were also somewhat of a community resource for the arts. Sometimes we’d get requests from various people to present curated shows at The Funnel. For instance, Vito Acconci came to town to do something with another artist-run gallery, so we were asked if the films could be shown/sponsored by The Funnel. (I think that one was under Michaelle’s aegis.) Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party was shown at The Funnel, co-sponsored with another group. We did a number of shows in co-sponsorship with the AGO, and so on. Toward the end of my tenure, I was really interested in trying to show more work by women, particularly in the context of feminism, so I’d try to use whatever contacts I had to curate shows that explored those issues.

There was also the fact that we exhibited visual art in the gallery/lobby of The Funnel. Artists like Fast Wurms did installations in the gallery that would be accompanied by screenings of their films in the theatre. I think we did have a gallery committee, but because we were a pretty small group there was a lot of discussion and collaboration, so programming was consistent between the two spaces. Kathryn Elder, who was a film librarian, did an excellent series of historical films for several years. We also tried to have members’ group shows at least once a year. A few times we picked a theme and provided everyone with a roll or two of super 8 film. The results were really fun. And of course, there were always the monthly open screenings.

One of the perks of being a core member (apart from having first dibs on those dreadful doughnuts and that coffee we sold) was the right to have your work shown at The Funnel. This wasn’t really a problem. Most films that members made were quite short, so they could fit into group screenings. If someone had a new film, everyone would already know about it because we were also a collective of filmmakers. I don’t think members would actually have to apply or anything. I always just did my best to accommodate them. When filmmakers made longer or more major works, we’d give them their own show. I didn’t always like everyone’s work, but I thought the principle was more important. I cringed during the odd group screening, in fact! But you know, the films that weren’t all that good were generally made by filmmakers who weren’t all that serious about making films, so they didn’t produce a lot, and being asked to show reams of work I didn’t like never became a problem for me while I was programming.

We also had a lot of visiting filmmakers. Typically, there were two or three guests each month, but we had no money for hotels and so they stayed with members, often with Ross and me. Later, when Ross and I stopped living together, visitors frequently stayed with me. Sometimes I’d clear out and let them have my place to themselves. My cat, Napaloni, developed a meaningful relationship with Kenneth Anger that way. And yes, it was a wonderful way to get to know people. I think Michaelle also put people up, but I’m not sure who. We tried hard to be good hosts to our visitors. Because they weren’t being paid much, we’d feed them and buy them beers after the show. Sometimes we’d take them sightseeing. Happily, we also received a fair amount of reciprocated hospitality that way.

There was also a lot of topical programming. If there was new work out there, then I would often show it because it was the living work of the contemporary film/art community. There was a growing interest in narrative in the early 1980s, and that often got interwoven with feminist filmmaking. I tried to accommodate as much of this kind of work as I could, although I really didn’t buy the argument of some feminist theorists that feminist film was necessarily narrative in form. I saw lots of work that plainly showed that wasn’t true, but it never got the academic press that the big girls’ work did. As time went on, there started to be more gay and lesbian experimental film being made and shown. We brought Ondine to the Funnel to screen some Warhol films. Jerry Tartaglia came with him and did a screening of his own work and discussed gay experimental film. Midi Onodera, who was our equipment manager later on, began to make work that pushed those boundaries, as well as the ones confining filmmakers of colour. She and David McIntosh really achieved a lot in terms of broadening the conversation, so it wasn’t just the white male formalists. I think if the Funnel had continued in a similar direction, it would have been decidedly less white and less male as time went on. As far as formalism is concerned, the high formalism of the 1960s and 1970s was pretty much a historical blip, as far as I can see — not just in film, but in most art forms. Postmodernism threw that trajectory way off, so I can’t imagine who is being nostalgic for some ‘good old days’ of white male formalism, but most of all, I can’t imagine why.

I think part of the transformation we were working for actually happened, but it was thoroughly, and probably predictably, co-opted. And while the uses of images changed, mostly the social piece didn’t. I remember going to see Rumble Fish by Francis Ford Coppola in 1983 and realizing that some of the formal innovations that artists had been developing in centres like the Funnel, in countries around the world, had been taken up as a style. An avant-garde ‘look.’ So in addition to the more radical project, I think there was a zeitgeist of people internationally wanting to do something about the stultifyingly predictable form of mainstream American movies. The growth of music videos was the culmination of that, I suppose. For a while, every new art student and film student had ambitions to make the next Duran Duran epic. Remember that? Of course, Kenneth Anger was a definite precursor, and he was mightily ripped off. There were a very few that were actually transcendent (I’m thinking of one by R.E.M.) and eventually the novelty wore off, as it does with all stylistic flourishes. Nowadays, things like jump cuts, fast-paced impressionistic montage, action without establishing shots, the rearrangement of the temporal order of sequences, and so forth – in other words, filmic gestures that break what were the ‘rules’ at that time – aren’t even remarked upon.

Mike: How much influence did the “old masters” of experimental filmmaking have on your curatorial choices? Did you have favourites?

Anna: I liked Michael Snow’s work a lot, but Paul Sharits’ stuff didn’t do it for me all that much. Nor was I ever a fan of Stan Brakhage’s work. We did have P. Adams Sitney at the Funnel as a co-sponsored program with the AGO, but even though he drew a crowd, I wasn’t really all that interested in what he had to say. It seemed to be old already. But these personal preferences probably don’t tell you much about programming tendencies.

I really loved the materialist aspect of Michael Snow’s films. They seemed to offer a way to branch out into different things. I think his work inspired other filmmakers at the Funnel. Joyce Wieland’s films always excited me, too. I’d say that Joyce and Mike were equally important to me even before I was making films myself. I loved the way Joyce was political and personal at the same time, and the way Mike was minimal/formal and spiritual. As far as the “older generation” of filmmakers was concerned, Kenneth Anger was a filmmaker whose work I loved. Does he count as a white male formalist? His work was sensual, transcendently so, I think. And transgressive in its own quiet way. I liked Owen Land’s work, too. He wasn’t all that much older than we were, but he was part of the “canon.” His work seemed a lot more youthful than some of the other white guys. It was funny and inventive, and formally, it was much more connected to popular culture.

New Improved Institutional Quality: In the Environment of Liquids and Nasals a Parasitic Vowel Sometimes Develops by Owen Land

So I guess for me, what I took from the generation of filmmakers that preceded us, the so-called “old white guys,” were a lot of different qualities that I subsequently looked for in upcoming work, including my own. The merging of the personal and the political; a meditative, materialist interest in the image; visual sensuality; the transgression of mores and expectations; and the ironic embrace of tropes from pop culture. All of these, I think, created a space for opening up possibility. The people I mentioned as inspiration were certainly white. But I think they were a lot more anarchic than they seemed to be once their work started to appear between the covers of learned books.

Mike: People often talk about duration as key to understanding experimental film of that era. How did that enter into your evaluation of film aesthetics and activities at the Funnel in general?

Anna: I think the meditative states that arrived in viewing films were also present in the process of making them. Compared with video, which allowed you to see and hear instantly what you were making, film was an act of faith, and an enactment of rituals that included both risk-taking experiment and honed skill. It was time-consuming and time-preserving.

Michaelle is a wonderful friend. She’s probably my favourite person ever to just do stuff with. We’ve travelled together, and worked on more than a few hare-brained schemes — and always with a sense of the extremity and ludicrousness of whatever we were up to. Once, after we’d gone to South America together, we got the idea to paint the Funnel gallery this deep terracotta red that we’d seen on some beautiful colonial buildings down there. We did it over a weekend. Some of the members hated it, and the following weekend, John Porter and a crew surreptitiously re-painted it white. I remember Michaelle and me putting up posters around Toronto in the middle of the night for an anti-censorship dance. And she’s has come to my rescue numerous times with the ridiculously arduous task of putting my summer cottage to bed for the season. What an incredible work ethic – she can work like a maniac! And then, when we take a break, it’s all elegant drinks on the front lawn, just like we were ladies of leisure. An amazing sense of style.

Michaelle had met my brother Jim (which is how we met) at Alvin Filsinger’s organic farm, north of Kitchener, where the two of them were among an army of willingly unpaid hippy slave-volunteers on the farm. I don’t know if you’ve ever planted and grown anything, but if you have, you know the unbelievable joy you get in seeing seeds you planted come out of the ground. I think there was something of that idea of planting the seeds of the Funnel, getting it to grow, having a community that nourished the seeds, and all that kind of hokey imagery. It all had a kind of organic feeling to it in the early days – not in the aesthetic but in the organization. Of course gardens die and have weeds and diseases and all that, but you always start out hoping that those pictures from the seed catalogue will materialize into your kitchen one day.

Mike: What do you remember about early Funnel members Adam Swica and Frieder Hochheim?

Anna: I’m trying to recollect Adam. I remember him getting extremely tanned in the summer and having piercing dark eyes and a surprising flop of straight, sandy-coloured hair that hung down when he looked in a camera viewfinder. I remember that he was very creative visually. I don’t remember much about his films, but I know they were inventive and great to look at. He did the cinematography for Mary Mary, and he captured exactly the look I wanted — even took it beyond what I thought was possible. He was the one who came up with the idea for our Funnel t-shirts — the word “Funnel” scrawled in white chalk on a black background. We silk-screened the image on black sweatshirts and t-shirts. I thought it was brilliant — original, minimal, and a little bit anti-establishment. They sold really well — until somebody stole our entire stock (whoever it was must have really liked them!)

I don’t think Adam was as interested as some of us in the idea of experimental film as outsider culture. Adam became good friends with another Funnel member, Frieder Hochheim, who was a recent Ryerson grad. Frieder got a job working as a gaffer (or best boy or something) on a Hollywood movie being shot in Toronto (it was Prom Night, with Jamie Lee Curtis). He got Adam a job working with him. I don’t know if you remember that period. It was the era of the tax credit, and it was when Toronto, for a while, became “Hollywood North.” Anyway, Adam and Frieder started their own lighting company called Star Sparks (or Sparx?) Adam rented a seriously gigantic space on Queen Street East, very close to the Funnel. His focus was more and more on working in the industry and developing his talents as a director of photography on bigger films. Adam’s studio was so ridiculously huge, it even had a mezzanine. Someone had an anti-censorship fundraising dance there, which was packed. I remember Andy Paterson doing a James Brown cover complete with the assistant with the cape trying to lead him offstage!

Frieder was probably the most successful of all former Funnelites: He moved to Hollywood and invented and patented the “Kino-Flo” light, which, last time I checked, is used on just about every film or video production going. I understand he’s very wealthy now.

Mike: Many screenings ended with a silence broken only by the passing streetcars as the artists, often from far away, waited for a peep from the crowd. Attention was rapt, but question period was often a strain.

Anna: I guess it’s true that people didn’t talk, but I recall that a little differently. I know I thought a lot about the films and talked, too. Probably not much in public, but I talked at length with filmmakers and other people at after-screening get-togethers, and I was sometimes frustrated that we couldn’t expand that. That’s why I started writing reviews and publishing interviews in the Funnel Newsletter. Theory was a difficult language for me, being self-taught, and I felt self-conscious speaking it where I could be criticized by those with more formal training. But for the most part, I think the problem with talk was that there was a really important class thing going on. Many people in the Funnel cohort grew up with deep suspicion of intellectuals — people who told the working families they grew up in that it was wrong, in some way, to want the goodies the middle class did. International struggles toward a classless society were concepts that intellectuals used. Many of my friends’ fathers had been on strike when we were kids in Hamilton, and we all knew the deprivations that had caused. The families knew about unfairness in their bones, but they were damned if they weren’t going to buy consumer goods when that wage settlement finally came through. It’s like the punk bands that discovered the plug had been pulled on Crash ‘n’ Burn – just because the boys upstairs didn’t like the fact that they wanted record deals. Fancy talk — from bosses, or from university-educated socialists — wasn’t something that would lead anywhere useful or fulfilling, was the feeling, and it was more likely to be turned against you than for you.

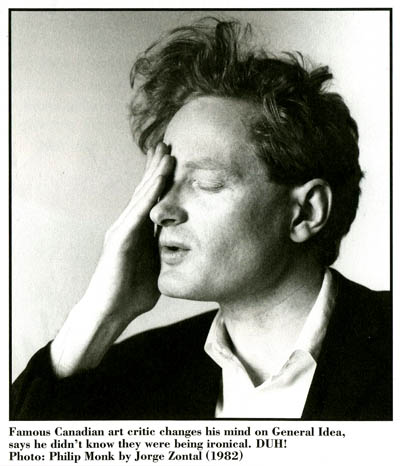

There was also, I think, until the early eighties, a kind of taboo about getting too theoretical amongst artists of all stripes. It had to do with what people understood about art. As New Painting and postmodernism caught hold, Christina Ritchie and Philip Monk put together a series of lectures called Talking: A Habit, at the Rivoli, and later published in Parallelogramme. The lecture series was supposed to get people to acquire the habit of talking about art. And I think it surely did. There was a strong feminist undertone to this, and a lecture by Philip I think alienated a lot of people in seeming to dismiss the work of some local male artists. (I was also asked to give a lecture. I’d never done anything like that. I read a ton of books to make myself feel/seem smarter and made my arms numb with writing and typing. I was shaking in fear when I finally stood up to talk, but I wasn’t laughed off the stage.) These details aren’t important historical facts, but I just wanted to get across the fact that talking was not a habit, and there were social, political and cultural reasons for it.

Mike: Were you surprised about what happened to the Funnel after you left?

Anna: The idea of community was the Funnel’s greatest strength. But in the end, this ideal devolved into an us-versus-them mentality which entrenched marginality for its own sake. There was always that reluctance to discuss art issues in a very deep way. One reason may have been class, as I mentioned before so I think there was a lot of wariness about any talk that smacked of academicism. Another reason was probably a fear of discussions that could exacerbate our differences and cause rifts in our small community. And ultimately that inability to deal with difference was what enabled that garrison mentality to take hold. The group was pressured from within because non-white, women, and lesbian and gay members were in a minority, and there was resentment and defensiveness about that. There was pressure from outside, too. We were the only place around showing non-narrative, independently made films, and a lot of people felt that the organization should be for them. It wasn’t like the visual arts, where you may get turned down by one gallery, but there’s another that would love to show your work.

Mike: Could you talk about your long engagement with the Ontario Censor Board?

Anna: When I donated all those documents to Queen’s University this summer, I thought I was leaving the anticensorship debacle behind me, once and for all. I looked through the material before sending it off, just to remove personal letters and the like. In the process, I came across a couple of things that surprised me. Over the almost thirty years since the events had happened, these documents had completely slipped my mind. Perhaps it was a willful forgetting, as they evoked unpleasant memories. And for that reason, I just glanced at them and didn’t pay a lot of attention to the details. Once you contacted me, however, I started to think a lot more about those particular items.

The first was an article by John Bentley Mays in the Globe and Mail where he attacked a new policy of the Censor Board, and by implication, the response of the Funnel, which had unhappily submitted to that policy. Seeing the Globe piece brought back the fact that the arts community was not always united in its strategies and perspectives. There was even some name calling. But over time, we all seemed to gradually find a way to work on several fronts so that differences of tactics became a strength, not a weakness.

The second item I came across was a letter that I had written to the Censor Board. I was responding to a communication from them in which they had offered the Funnel some kind of special “deal.” My letter declined their offer on the grounds that we weren’t alone in presenting the kind of programming we did, and that any “deal” for us should be extended to everyone. I wish I could remember more about this: what the deal was, when it was offered, what the context was, and so on.

That letter made me remember how very complex the whole protracted conflict was. The Censors were under pressure to change — both from us, the anticensorship activists, and from the Ministry of Consumer and Commercial Relations, who wanted them to squirm their way out of the legal challenges being brought against them. Of course, the government only wanted changes that would maintain the status quo but make us shut up. Anyhow, things were constantly changing. We (the Funnel, OFAVAS, FAVAC, and the community in general) continually had to adapt our strategies in response to new “weapons” the Censors were throwing at us

As I’ve thought about all this, it seems to me that the untold story is really about the complexity of the struggle and how the “anti” side developed over time — from the isolated persecution of the Funnel in 1980, to the extensive ad hoc coalition of individuals and organization that mobilized to screen Paul Wong’s Confused: Sexual Views at Artculture Resource Centre in 1984 and continued to act cohesively, but also independently, as needed, at points after that.

I was remembering the renos and dealing with our neighbour — the business below us was named ‘Jean’s Cutting.’ They cut out fabric for clothing, using huge cutting machines. Do you remember that during screenings there would be huge thumps every now and then? That was Jean stamping out another batch of shirts. Anyway, we had to cover the ceiling of their space with special fireproof drywall, so we had to wait for them to go on holiday. Then we had to work around all their really expensive machinery and tables piled high with stacks of fabric — all of which were covered — but it was still a horrible job trying to work over top of all this stuff without wrecking any of it.

I don’t remember details of who launched which court cases, and when. I know things happened quickly. Court cases came and went. While at first it was just the Funnel that was persecuted, from time to time, other organizations also became the victims of censorship and thus they would become the focus of much of the community’s resistance. The Funnel was first asked to submit its films to the Censor Board in 1980, and by 1981, the Funnel, CFMDC, Canadian Images and Fuse Magazine were all involved in court cases involving the Censor Board.

I still feel a certain need to justify, or at least explain, the Funnel’s strategy against the Censor Board under my directorship (not least because of criticism such as that from J. B. Mays). We were stunned when the Censor Board first told us they wanted us to submit the films we showed. We assumed at first that this was some kind of error; surely the censors — who were, we supposed, on the lookout for porn and extreme violence and material that would disturb kids —couldn’t be interested in us. But it turned out they were. We asked everyone we could think of who might have knowledge about the Censor Board if there was anything we could do. Everyone stressed that if we defied the Censor Board, they would very rapidly shut us down. So we complied.

Submitting to the Censor Board turned out to be a pretty controversial decision, and it was a terrible decision to have to make. It certainly didn’t make things easier for us. But we felt that rather than be totally silenced we would comply — and complain as loudly and publicly as we possibly could. We agreed that we would never not program a film based on whether it might be censored or not, or whether a filmmaker might refuse to submit to censorship or not. If the Board demanded cuts from a film, or wanted to ban the film, we would not comply; we would cancel the screening instead, pay the filmmaker (and of course, apologize profusely), and make a huge public stink about it.

To that list of the infuriating aspects of being censored, I should add particular emphasis on the effect on filmmakers. It was horrible telling touring filmmakers from other parts of the world that they had to arrive in Toronto early so that their films, along with a fee we had to pay, could be couriered to the Censors’ offices up in the suburbs, screened and stamped — if you can believe it — with a special stamp of approval, and then shipped back to us with a permit before the screening. This sometimes meant delaying screenings while we waited for films to be returned to us. And of course, our members and other local and Canadian filmmakers didn’t like it any better than the international filmmakers did. Once we had American filmmaker Larry Gottheim showing a brand new print of a film that had recently been included in the Whitney Biennale. Poor Larry rushed to get to the Funnel and was very gracious about going along with the ridiculous local custom of censorship. But when we got the film back from the Censors, it was not only stamped, but had a large scratch on it. Eventually, by making a whole lot of noise about it, we managed to get the Censor Board to pay to replace that reel of film. But it took a lot of work to achieve that, and it had been a humiliating experience and the opposite of good hospitality.

Unfortunately, I don’t have the complete record of events, so I can’t tell you exactly when and how certain things came to pass, but I do know that at one point, the Censor Board agreed to a system they called “Examination by Documentation.” This meant we had to fill in a form outlining the content of the films, running time, etc. This was no less morally despicable (some would say it was more so), but it was somewhat easier. Nonetheless, the Censors retained the right to demand to see anything they felt like seeing. I always wrote very vague descriptions of the films, that couldn’t have really suggested any “need” for them to see a film, but their whole schtick, of course, was just control. The other “concession” they made was that they agreed not to stamp films any more. I’m sure the new system was mainly instituted to make things easier for the Censors and to try to silence us. I’m just guessing, but I would imagine that after they’d seen some of the flickery, grainy, abstract, or sometimes very long films we often showed that they were beginning to realize they didn’t really want to see this stuff after all. Obviously, however, they couldn’t and wouldn’t back down.

It was probably due to pressure from the Ontario Arts Council that we got that first small change in policy from the Censor Board, allowing us to submit information about a film, rather than the film itself. An interesting aspect of all this was that the Censor Board was part of a branch of the Ontario government. And the Ontario Arts Council was an arms-length government agency, and the OAC funded the Funnel. This contradiction was one we thought we could probably use to some advantage. In fact, the Arts Council was quite supportive of our position. Many of its other clients were organizations very similar to ours (although we were the only one that showed film — as opposed to video — on a regular basis). OAC seemed to want, I think, to just remove the cultural/non-commercial work of their clients from the censors’ mandate.

I, and others at the Funnel, believed that if the censors could experience us as a huge bureaucratic nuisance that they’d be much better off without, we (with the help of the arts council and, hopefully, other members of the cultural community) might be able to get the government to amend the Ontario Theatres Act to include an exemption for “artistic expression.” The argument that would be used was that the Criminal Code recognizes the category of “artistic expression” and does not subject works to “prior restraint”—the term used to describe submitting works to approval before they are publicly released. The Theatres Act could trust the Criminal Code to test for obscene or illegal material, while allowing artists to defend their work as artistic expression if a charge was laid. Based on this argument, ours was a strategy of hostile compliance with the goal of changing the law itself. We saw this as a pre-emptive strategy, that could possibly (eventually, and hopefully), spare other organizations like ours from being subjected to what we had been going through.

There were other people, however, who disagreed with our decisions — both to submit films for censorship and to provide “documentation” on films. The Globe article by John Bentley Mays was furious at the idea of “examination by documentation.” The gist of the piece, I believe, was that artists’ groups who went along with this system were more or less collaborators — in the worst sense of that word. Mays wasn’t alone in this opinion. I won’t go into details about who said what; let’s just say there were some nasty insults and accusations hurled. It was uncomfortable being thought of as politically incorrect. In the early 1980s, many in the arts community didn’t have a very nuanced notion of cultural politics. What Mays and others who took his position failed to acknowledge was that the Censor Board had been exercising exactly the same kinds of rights to censor commercial films for years, and none of them had spoken out about it at that time. In effect, I believe we were being blamed as victims — especially because we were young, marginal, and artists, and in my case, I suspect, because I was young and female.

Honestly, I don’t know if what we did was the right thing or not. I do believe, however, that if the Funnel had decided to simply defy the censors right off the bat, we would likely have been charged with violation of the Ontario Theatres Act and forced to defend ourselves in court. This would probably have lead, eventually, to the Funnel being closed down, as we didn’t have the resources or, at that point, the community support, for a court battle. Whether, following our potential demise, the Censors would have spread their net to pick off other arts groups, one at a time, or not, is hard to say. But, because we chose to remain standing, so to speak, with our continued public existence being our chosen means of defiance, I think a groundswell of public opposition to censorship gradually grew — to the extent that the Censors couldn’t isolate any one of us, and it had to be acknowledged that there was a serious problem.

Things really started to take off when a package of films put together by the National Gallery of Canada (it was called Canadian Filmmakers Series IV) was scheduled to be shown at the Funnel in September 1980. The Censors asked for cuts to the film, A Message From Our Sponsor by Al Razutis. Of course, we said no. The National Gallery was willing to drop the film from the package, but none of the filmmakers agreed. There was a long, complicated period where I helped to organize a protest on behalf of all the filmmakers whose works were in the film package and to get the National Gallery to agree not to drop the film. Ultimately, the film was shown. I’m sorry I don’t recall all the details. I think that the Censors gave “one time only” permits — that would have to be re-applied for if future screenings were planned — to the Funnel and the AGO. Hardly a major victory, but at least, a certain show of strength from the artists’ community.

Where this all leads is to the spring of 1981. I was a programmer for an experimental film program at the Canadian Images Film Festival in Peterborough, Ontario. One the films I helped choose was Al Razutis’s A Message From our Sponsor. I don’t remember exactly what the Festival’s relationship with the Censor Board was at that point. Probably they just didn’t submit anything, ever, but I don’t actually recall. At any rate, the Censor Board found out that Al’s film was going to be shown and they raised hell. They said it couldn’t be shown without cuts. Of course no one intended to allow any cutting. The festival executive decided they would put on a public screening of the film, regardless.

This put me in a funny position as a programmer at both the Funnel and at Canadian Images. The Funnel’s policy was to not show films the Censors wanted cut, but Images’ newly coined policy was to show them. I went around and spoke to each person who was responsible for making that decision. I suggested that they could take the same position as the Funnel, in solidarity, but if they didn’t, I would be forced to resign. I think I made it clear that it wasn’t because I disagreed with the principle of civil disobedience, but because the positions of the two organizations were so different that I couldn’t support both simultaneously. And my greater loyalty — as an employee and Board Member of the Funnel — had to be to the Funnel. I’m not sure everyone understood that this was a dreadful choice I felt I had to make, especially as I was actually later subpoenaed and had to testify against my colleagues from Canadian Images.

The Censor Board, maybe inevitably, brought charges against Canadian Images. After the Funnel’s troubles, the Series IV debacle, and now, Canadian Images, it was like an alarm bell had been sounded in the Toronto arts community. I think everyone started to realize that this wasn’t going away. Lisa Steele and Clive Robertson called a meeting at Fuse Magazine’s office. It was great that now the video and wider artist-run community was interested in actively helping with the fight.

There was lots of debate about what to do, at that meeting. Many people felt that another screening in defiance of the censors was a good idea. I wasn’t too sure if this was the best strategy. Finally, Gary Kinsman, a member of the gay cultural/intellectual community, spoke up and convinced everyone that before we got into that kind of an action, we should think seriously about what we wanted to achieve. Gary made an extremely important contribution to our being able to start to strategize as a community, rather than just react. We decided that we would form an organization: Film and Video Against Censorship (FAVAC), set out our demands, and we would do a public forum on censorship.

Complicating all this was the fact that at the same time as our problems with the censor board there was a growing pro-censorship movement among feminists! (See my reference, above, to black-and-white political thinking in the early 1980s.) It seems strange to think of this today. But Andrea Dworkin and other feminists were getting militant about pornography at around that time, and for many feminists, censorship seemed like a great solution.

(I’ve often thought that one of the main reasons that film and video censorship really started to heat up at that particular time was that cheap portable video equipment — for both recording and playback — started to be available at around then. Coinciding with this historical moment was a surge in the critical mass of a “second wave” of feminism in North America and Europe. I think that governments, and possibly corporations, began to wonder whether they might lose their control of images, while simultaneously, women began to wonder who controlled their images. These two social moments intersected and sparked a whole set of repercussions.)

Following the meeting at Fuse, a sub-group met at someone’s house. I remember lots of discussion and genuine puzzling about how we could be both feminist and anti-censorship. Some people like Varda Burstyn, who were more political than arts-oriented in the direction of their work, were truly struggling to envision a position that embraced both. It was a really good meeting because we were all working as a group to figure out and define the ideas that could make all this make sense.

The public forum was held in the building which had recently housed the Mirvish Gallery on Markham Street. The speakers included Varda Burstyn, Gary Kinsman, and me. (There may have been others — I have a memory gap here) We had great attendance and decent press coverage. The local cable station ran the whole forum on TV.

It was difficult to maintain a regular schedule of meetings that a lot of people could attend, but I think FAVAC was really helpful anyway. I was among a small group of Toronto-based people who did attend whatever meetings were organized.

David Poole may remember better than I do how this happened, but somehow in all this, FAVAC managed to hook up with Lynn King and Charles Campbell, who were young, brilliant, politicized, and energized lawyers. I think we may have met them through June Callwood. June’s son, Brant, was Film Officer at Ontario Arts Council, and I think that possibly Jane Gutteridge, who was then the Director of CFMDC, suggested to us that we should ask Brant to connect us with June. June was terrific. She knew everyone and could mobilize incredible support for a cause she believed in. She helped us with fundraising and I’m pretty sure she set us up with Lynn and Charlie. She would have known Lynn as a lawyer who worked for women’s issues, as these were something both women were deeply committed to.

With Lynn and Charlie’s assistance, FAVAC drafted a statement of demands, amendments we wanted made to the Ontario Theatres Act. We circulated these amendments at the 1981 Toronto Festival of Festivals and collected signatures supporting our position. The demands included asking that the Censor Board be changed to a classification board only, without the power to cut or ban. Another demand was the kind of exemptions for cultural and non-commercial film and video screenings that the Funnel had been hoping for. We canvassed Ontario’s cultural community — outside of Toronto, as well as inside — and got widespread support for these proposals. By doing this, we constructed a loose but committed network of individuals and organizations that could be activated quickly when action was required, even though we didn’t have a tight-knit organization that was active on a day-to-day basis.

I know that both The Funnel and the CFMDC at a certain point decided to launch our own lawsuits against the Censor Board, and our lawyers, Lynn and Charlie, worked for free, helping us form strategies and putting together our case against the censors. As I mentioned earlier, however, both lawsuits were dismissed by the courts because the Censors changed a few small aspects of their policies.

Eventually, after the first law suits had been dropped, Lynn and Charlie told us that they thought we could have a very good case under the new Charter of Rights and Freedoms that would become law in Spring of 1982.

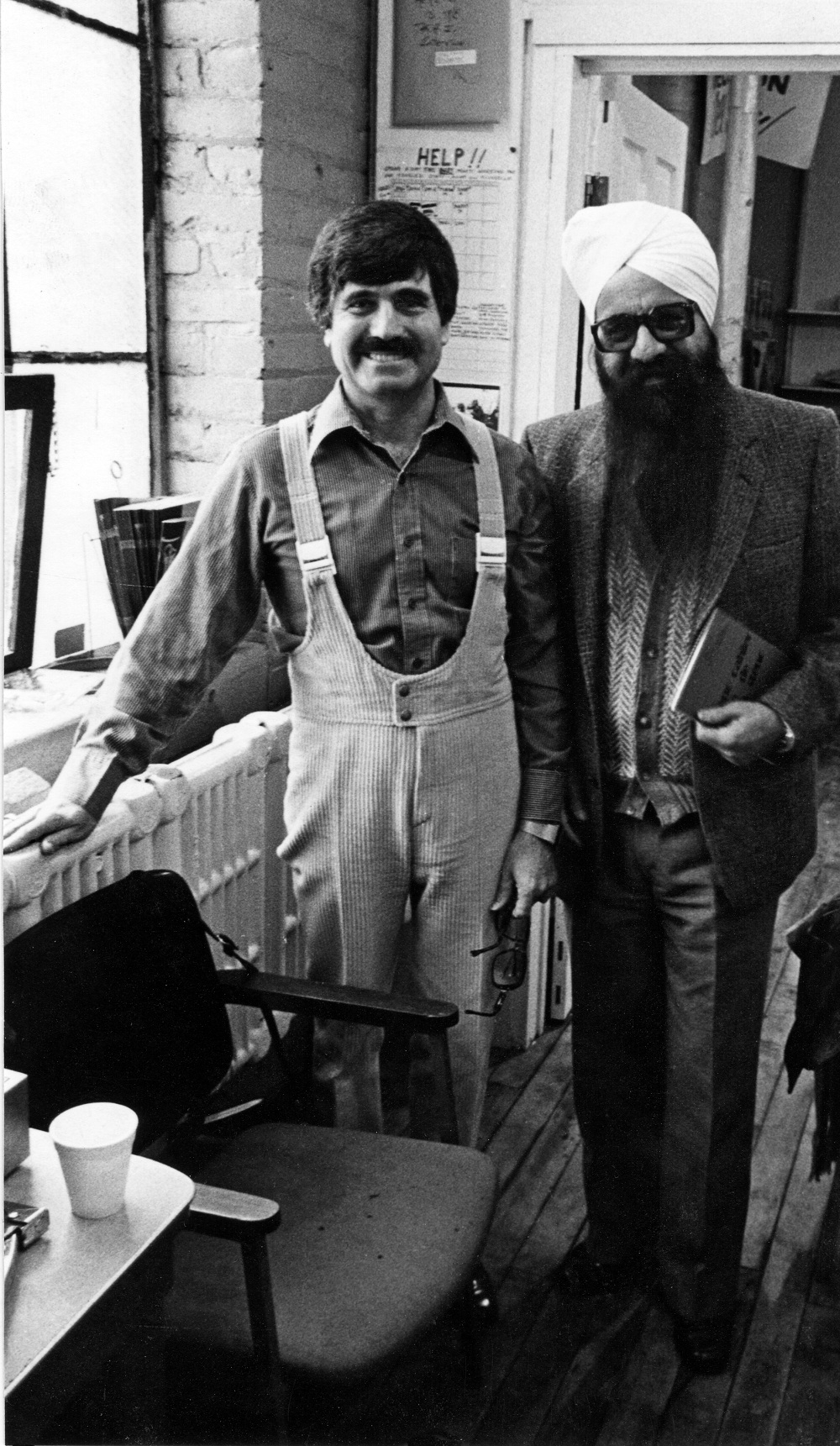

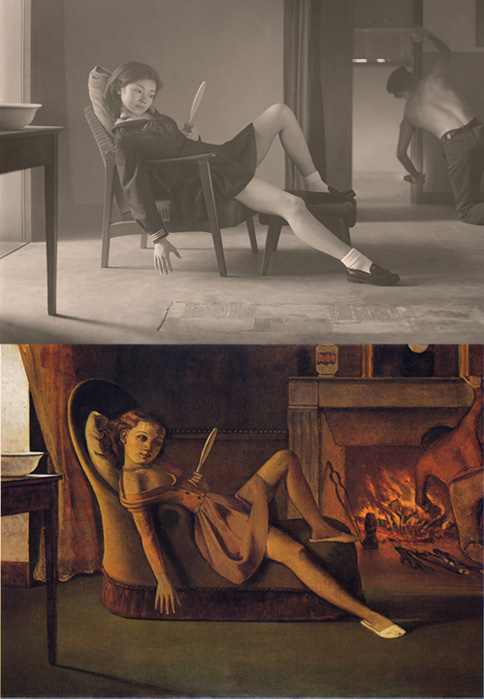

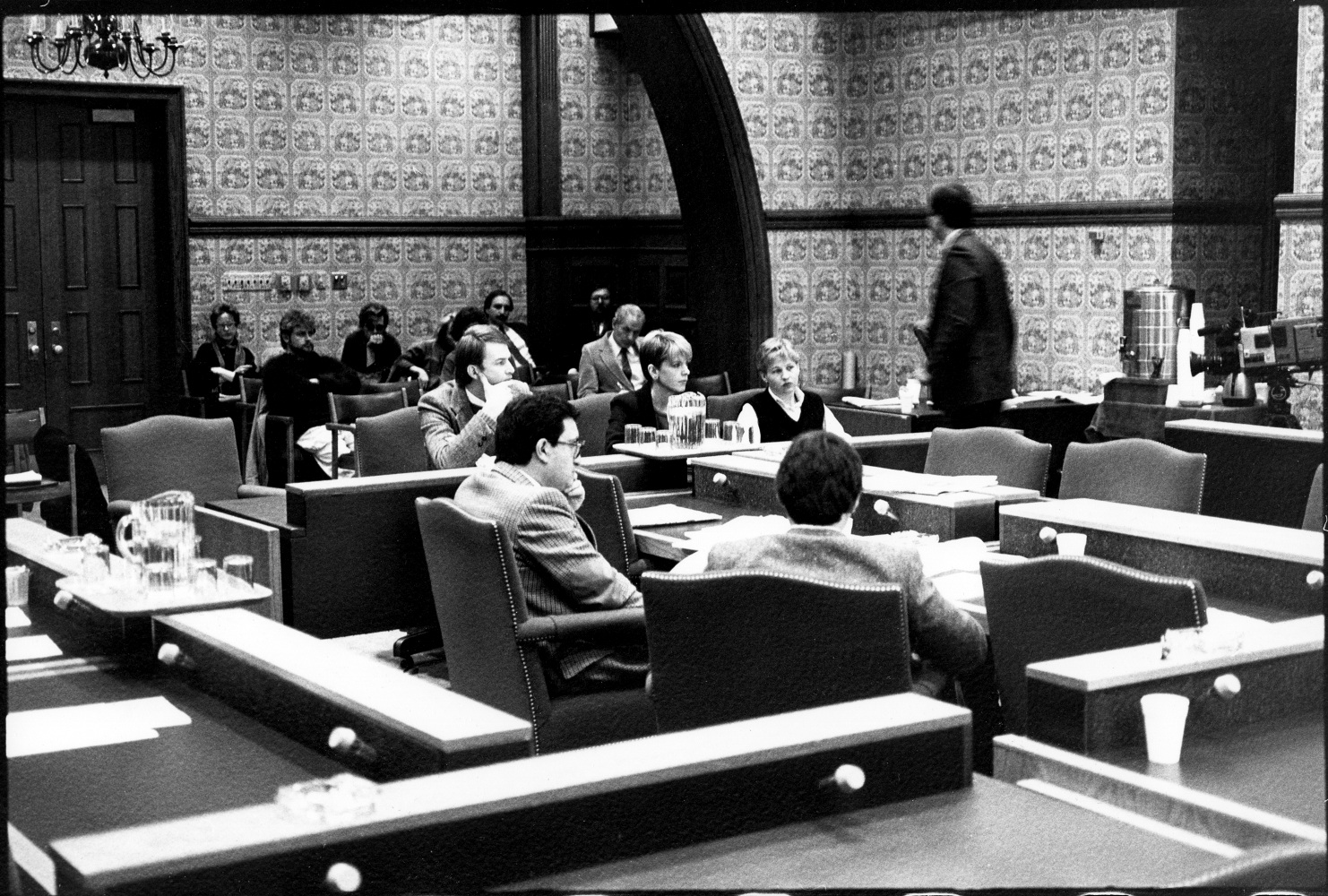

OFAVAS (David Poole, Anna Gronau, Cyndra McDowall) presenting a brief to a public hearing on Bill 82 at Queen’s Park, 1984 photo by John Porter

David Poole from CFMDC, Cyndra McDowall from Canadian Artists’ Representation Ontario (CARO) and I were all very active in FAVAC, while many other people came and went depending on what was going on. The three of us were involved to such an extent because the mandates and activities of our respective organizations made censorship something we were required to deal with constantly. On Lynn and Charlie’s advice, and after canvassing FAVAC members, it was agreed that a new organization would be set up that would challenge the Ontario Censor Board under the new Charter, and that Cyndra, David and I would make up the board of directors of that organization. I believe that we actually incorporated this new organization. As you know, it was called the Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society (OFAVAS). Ours was the first court case launched under the new Charter.

By the time OFAVAS was set up, there were beginning to be other sub-groups of people and organizations in the Ontario arts community who would, often under the loose aegis of FAVAC, initiate events somewhat independently, calling on the others for assistance, as needed. Pages Bookstore, Fuse Magazine, Artculture Resource Centre, to name a few in Toronto, as well as some arts groups outside of the city, took on anti-censorship activities of different kinds. To me, this ability to work simultaneously on different fronts, to pursue varying strategies, and to exercise tolerance of these differences were signs of the growing maturity and effectiveness of the movement.

The exhibition of Paul Wong’s video installation, Confused: Sexual Views, at Artculture Resource Centre marked the achievement of this maturity. It was the first open defiance of the Censor Board with really widespread community support. We showed Paul’s work without submitting it to the Censors, and advertised both the show and the protest. People and organizations from all over the province as well as beyond, not only wrote letters of support, but also signed on as “sponsors” of the event — so that if the Censors decided to charge anyone, they would have to charge us all. There was really quite amazing support. Of course the Censors did nothing. To me, this seems like the point at which the Censors’ ability to isolate and persecute was shown to be essentially over.

When I look back on that whole period it seems almost quaint, now that we have the internet, social media, Wikileaks, and so on. It seems strange that a provincial government would have expended any energy at all going after a few artists showing films. On bad days, given all the truly dreadful problems there are in the world, I sometimes wish we had mustered all that energy to help someone besides ourselves. On good days, I think we were all correct in believing that censorship of a few flickery, grainy, “long and boring” experimental films was simply the top of that slippery slope toward censorship of vital political information. I think how awful it is to be censored, and I think about places like China and Burma and Iran, and the awfulness of living cut off from information. That’s when I think that censorship is really worth fighting. I do, always, wish we’d achieved more.

Anna Gronau: The Dead Are Not Powerless (an interview) (2000)

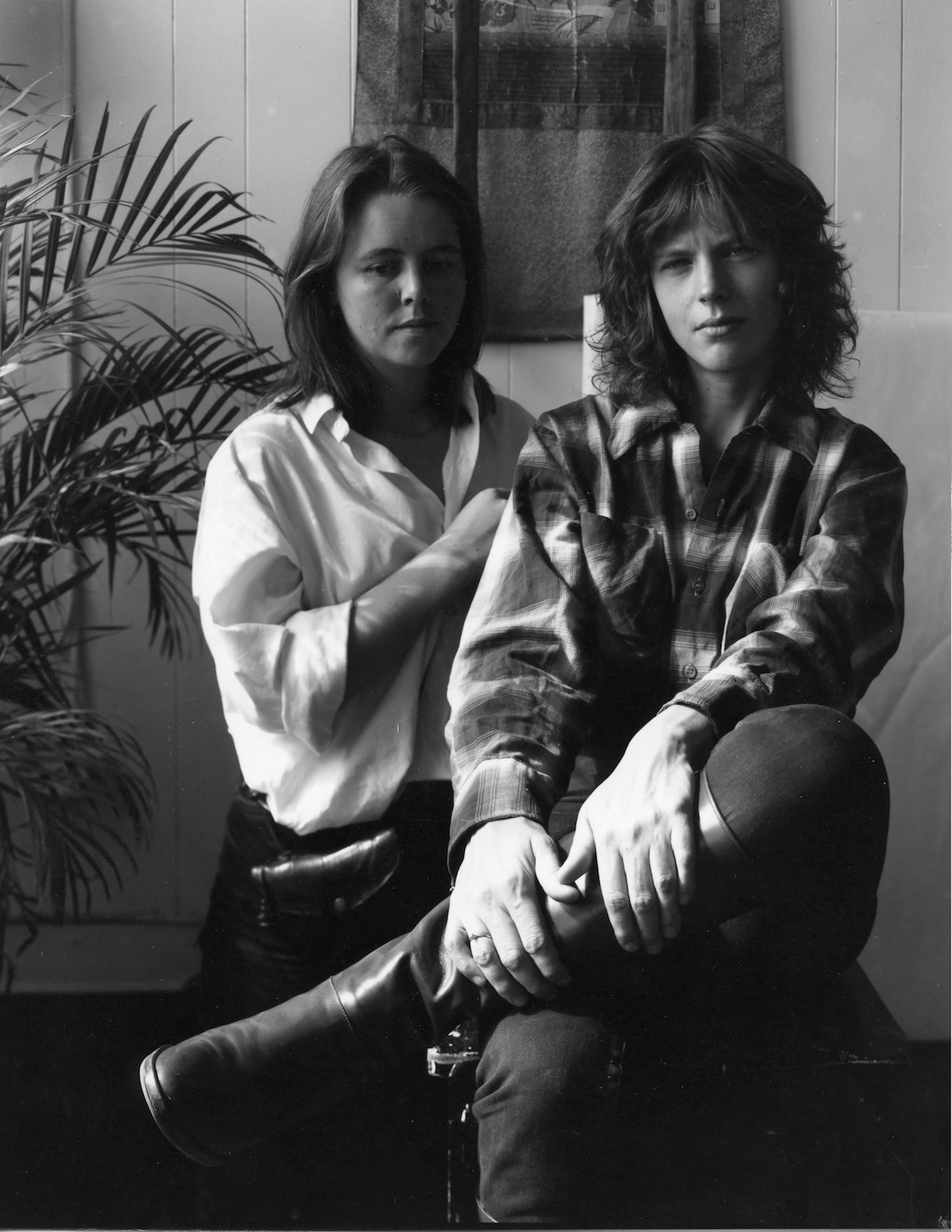

Born in Montreal in 1951, Anna Gronau moved as a teenager to Toronto, where she became a central figure in the city’s turbulent fringe-film scene. Between 1980 and 1982 Gronau was Director/Programmer of the Funnel Experimental Film Theatre, and from 1983 to 1985 worked as video distribution manager at Art Metropole. She has written and lectured tirelessly on feminism and the avant-garde, touring work and championing marginal expression. She also led the charge against the intrusions of the Ontario Censor Board. Rallies, protests, and politicking were capped by many hours in the courtroom interrogating government agents, exposing the capricious judgments and ambiguous standards applied to motion pictures large and small. While she was helping so many others, she was also quietly developing a body of work all her own. She appears in all of her early work, though it is the structure of cognition rather than the narrating of personal experience that impels her concern. The solitude that haunts her work is narrated in a succession of subtle and painful autobiographical moments — the ending of a relationship, the death of a friend’s child. Many of her films suggest ways in which the self can interact with an outside world, negotiating the divide between inside and out, between self and Other. Her later work has taken up politics in a different register, often using dramatic elements to unwrap the layers of history that occlude relations in the present. Her work asks us to remember, while showing us how.

AG: I got involved in film by coincidence. Back in high school, in Hamilton, I had a friend at McMaster University. We used to hang out at the Film Board there. It was a place where some ambitious young filmmakers — some of whom went on to be famous — were watching a lot of movies and planning their first films. I saw my very first experimental film there, if you don’t count the Norman McLaren films we saw as kids. Then, when I went to the Ontario College of Art, I met Keith Lock and Jim Anderson, who were studying film at York University. We all ended up living in a communal house around the time the first Toronto Filmmakers’ Co-op [a non-commercial production/post-production facility] and the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre were being set up. Jim and Keith and others in our house were very involved. While I was studying painting and sculpture at art school the whole notion of “avant-garde” caught my interest. I understood it at the time in its relation to the military idea of an “advance guard” — leading the way. My belief as a young art student was that avant-garde art would be taken up by people at large. I never thought of art as a permanently separated cultural activity. The idea that there were avant-garde films seemed completely natural to me. This was around 1969/1970. The counter-culture was still something people believed in. There was a lot of performance going on and anti-object art was big at the time. Idealistically, I believed that the ghettoized, even despised, status of avant-garde film was only temporary. As I remember it, avant-garde film wasn’t much different from alternative rock music in terms of the value that I and the people I knew felt it had. We saw all kinds of “youth culture” as being on the cutting edge — and leading somewhere. Otherwise, I don’t think we would have been interested. Of course, as we know now, rock music did “go somewhere” — and avant-garde film went somewhere far less dazzling! Still, I had high hopes for leading-edge filmmaking, although at the time I didn’t consider the problems of the notion of avant-garde, such as the way it assumes leadership and hierarchy.

The first film I made was for school, and Keith helped me. It was a “structural” film called Inside Out. I was living in an old farmhouse with a big picture window in the kitchen that overlooked an orchard. I set the camera on a tripod half an hour before sunset, turned on the kitchen lights, and filmed a kind of time-lapse out the window. I exposed a few seconds every couple of minutes. As the sun went down, the window darkened, revealing the reflection of me and the camera. The film was about ten minutes long, but I’m afraid it’s lost to posterity now. [laughs]

After I graduated, I helped Keith and Jim with their films and went to screenings and meetings of the Film Co-op, but I hadn’t had any technical instruction at OCA so I didn’t have the confidence to try making my own films. I lost touch with film for a while, and then in the late seventies, Jim Anderson, his brother Dave, and Keith started holding screenings at a studio at the corner of Adelaide and John Streets. The building belonged to a company called Freud Signs! The screenings helped me realize that I still wanted to make films. Then I heard about a filmmaking workshop at a new organization called CEAC, the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication. The workshop was associated with the Funnel, a program run by CEAC, which had been holding biweekly experimental film screenings just down the street from Freud Signs. The Funnel was in the process of setting itself up as an independent organization and that’s when I became involved. I felt it could help me both make films and see a lot of work. The first screening I attended featured films by James Benning. His approach to filmmaking showed the sensibility of a painter and poet, so with my art background, it began to look like the Funnel would be a good place to be.

MH: Can you describe CEAC?

AG: It released publications, staged performances, provided video access, and hosted conferences. CEAC also ran an educational program which included the filmmaking workshops I attended.

MH: Why did the Funnel separate from CEAC? Was it a difficult transition?

AG: Separation started before I became involved, but I think the idea initially was that the Funnel had a strong mandate and could likely function well on its own — get its own funding and so on. But many things started to happen at once. The Toronto Filmmakers’ Co-op was on the verge of bankruptcy. As I was told, it had lost its “alternative” approach and was being used as a low-cost quasi-commercial facility and was accumulating untenable debts. The Canada Council asked members of the independent film community to get involved and try to save the Co-op. A number of people who did so were also trying to help the Funnel get on its feet. The Co-op turned out to be in worse shape than we’d thought and eventually we had to declare bankruptcy and close it. But this wasn’t a unanimous decision. I think some filmmakers felt that the new board was simply trying to kill the Co-op and grab its funding. To the best of my knowledge, this wasn’t the case, but it made for a lot of tension. Meanwhile, CEAC began to take a radical militaristic, guerrilla- type stand. They were starting to say that art wasn’t enough — to change society you have to go out and shoot politicians. [laughs] This became a political hot potato when the Toronto Sun got hold of a copy of CEAC’s newsletter, Strike. The cover showed a picture of Italian premier Aldo Moro, recently murdered by a political terrorist group called the Red Brigade. CEAC’s editorial voiced support for the Red Brigade. The Sun declared its outrage about this on its front page, and all public monies to CEAC were quickly stopped. This really split the arts community. A number of arts organizations openly condemned CEAC. The Funnel was in the strange position of already trying to separate from CEAC. When CEAC demanded a letter of support from the Funnel, they were refused. In retrospect, that seems like it may have been cowardly, but CEAC wasn’t behaving very honourably, either. For a while there was a feeling that CEAC might try to seize the Funnel’s “assets.” In the end, we stored all the stuff — some chairs and tables and a projector — in someone’s basement and searched for another home for the new and separate Funnel. So, yes, it was a difficult breakup.

MH: How did the Funnel’s theatre get built?

AG: We finally found a location on King Street East. Within a month, using only volunteer labour, we turned a raw warehouse space into a one-hundred-seat theatre with a projection booth and an office space. We opened in January 1977.

MH: How many volunteers were there?

AG: About twenty. The “core” membership was always around twenty. Over the years people came and went, but the figure was always about the same.

MH: Was the initial idea to build a theatre for fringe film?

AG: Different people had different ideas. Ross McLaren, who had been involved while the Funnel was at CEAC, always wanted an equipment co-op. But that wasn’t feasible politically or legally because the Toronto Film Co-op was going bankrupt. You can’t declare bankruptcy in one organization and then start another that does the same thing. Some members felt from the start that the Funnel should be a cinematheque, and that’s what it was initially. But after a while we started to get some production equipment — at first only super-8 cameras — that was clearly outside of the old Co-op’s mandate. Later on, we also got post-production sound gear and 16mm cameras. We tried to set up an integrated and complementary facility in production and exhibition. For example, we purchased a good super-8 projector which could also be used to record sound in sync with the image as it was projected.

MH: How was it decided what kind of work would be shown?

AG: In the very beginning it was a mixture, based mainly on what we could afford: more established Canadian experimental filmmakers like David Rimmer and Mike Snow and Joyce Wieland, and younger local filmmakers doing personal, low-budget filmmaking. By the time I started working at the Funnel, there was a little publication called the Filmmaker’s Newsletter that came out of Minneapolis. They announced new films and screenings and screening facilities, and this created a circuit so experimental filmmakers could take their new works on the road. There was never any money. The Funnel had grants, which was more than some groups had, and we only paid an honorarium that may have just covered plane fare. But there was an international community that was excited to see and show work. We used to show experimental or avant-garde work from all over the world. There was a wide range; some films were very conceptual, some were highly politicized, others more diaristic. It was an exciting immersion. We held two different screenings a week, usually with the filmmaker present to answer questions and discuss her/his work. Frequently, our guests were from out of town or from another country.

MH: Did a lot of people come to screenings?

AG: There were a few devotees who came to everything. There were times when there’d be only ten people in the audience and others when we turned people away. It depended on the profile of the filmmaker. But we worked hard to spread the word. We made up little Xerox posters every few weeks and plastered them on downtown hoardings. That was better publicity in those days because not many people were doing it. Eventually we sold memberships and mailed out calendars every couple of months. Occasionally we got a write-up in one of the daily newspapers or in an art periodical, but that didn’t happen often. The best and worst publicity we got — it was inevitable that this would come up in a discussion of the Funnel — was from the Ontario Censor Board. I say this because the film censors made our lives extremely difficult. But the fact that we resisted their interventions resulted in a lot of media attention and the Funnel became much better known. At first, the Ontario Censor Board insisted that we send them every film we wanted to show a week in advance of the screening so they could classify it and mark the print with an embossed stamp. They also wanted us to advertise the film’s “rating.” Even if we hadn’t found the whole idea abhorrent ethically, it would have been impossible solely in practical terms. Filmmakers usually arrived with their work from out of town just a few hours before their screening. We protested and got all sorts of high-profile supporters to speak on our behalf, but the Censor Board refused to give up their right to preview and “rate” — and potentially ban from screening — all films we showed. For a while they would even send someone down to the Funnel to watch films on our premises before the screening. It was ridiculous. But resistance began to grow because the Censor Board, having more or less stumbled upon the Funnel (as far as we could tell) suddenly realized they’d opened up a hornets’ nest. I don’t think they had any idea of all the independent film and video activity that was going on in Ontario. David Poole from Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, Cyndra McDowell from Canadian Artists’ Representation, and I eventually became the board of a small organization that took on the Censor Board through the courts. Our group was called the Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society. We took the offensive, and charged the Censor Board with being unconstitutional under the Charter of Rights. The Canadian Criminal Code stated that if material was made public and the public complained, charges could be laid and judged according to community standards. But this was a hired board whose job was to decide for the public in advance what it could and couldn’t see. We argued that this prior censorship was unconstitutional. We had some legal victories, although we were obviously the underdog in terms of resources. I think we won mainly in the sense that we revealed the ludicrous nature of many aspects of the current legislation. But it was an ongoing struggle. By the time I left the Funnel, we had won a small amount of leeway: the Censors required only that we submit a written description of films we planned to screen. They still retained the right to ban a film, however.

MH: Tell me about the Open Screenings.

AG: These started when the Funnel was still part of CEAC. The idea was that once a month anyone could bring her/his film and it would be screened publicly. Films ranged from home movies to student films to offbeat stuff that you might imagine strange people had obsessed over in basement editing dens. To tell you the truth, I liked the idea of Open Screenings better than the reality of them. They were often tedious and boring. Then the Censor Board made open screenings illegal because people who just showed up with their films couldn’t submit their work to the Board before they showed them. We saw this as a real affront to the notion of freedom of expression.

MH: Did that affect public opinion about the Censor Board?

AG: I think it contributed to making the censorship laws look silly, but actually, I think it was the huge number of run-ins with the arts community that gradually undermined their credibility. The last straw was when they started to mess with the Toronto International Film Festival. That was truly politically embarrassing. The Censor Board had already lost a couple of times in court, but it was not until they found themselves in a standoff with the Film Festival that they started making accommodations. Unfortunately, not much has changed. We still have a Censor Board, and, just like before, the law is full of loopholes. Our argument had always been that the law was wrong and dangerous, and the fact that it might not be enforced to the extent of its full insanity didn’t make things any better. The law still gives the government power to infringe extensively on freedom of expression if and when they are so inclined. Today most “fringe” media is exhibited in an underground setting — without the Censor Board’s knowledge. We’re back where we started.

MH: Was there a common ideal at the Funnel?

AG: The idea of community was the strongest link. But in the end, this ideal devolved into an us-versus-them mentalitywhich entrenched marginality for its own sake. There was always a reluctance to discuss art issues in a very deep way. One reason may have been that many members were from working-class backgrounds. Intellectual posturing and intimidation has often been a way to keep working-class people “in their place,” so I think there was a lot of wariness about any talk that smacked of academicism. Another reason was probably a fear of discussions that could exacerbate our differences and cause rifts in our small community. But ultimately the inability to deal with difference was what enabled that garrison mentality to take hold. The group was pressured from within because non-white, women, and lesbian and gay members were in a minority, and there was resentment and defensiveness about that. There was pressure from outside, too. We were the only place around showing non-narrative, independently made films, and a lot of people felt that the organization should be for them. It wasn’t like the visual arts, where you may get turned down by one gallery, but there’s another that would love to show your work. I think we hurt some people’s feelings and I regret that. But anyhow, that’s dwelling on the negative. On the bright side, there may not have been an articulated “ideal,” but there was great excitement and enthusiasm surrounding and within the Funnel for a while. Lots of outstanding work from all over the world was screened, including a lot of locally made films. There was a feeling for a time that something important was happening. We had a gallery for visual art there, for example, which made an important link with that community. Younger people, just coming out of film school, were encouraged to pursue filmmaking because of the sense that a vibrant independent film scene existed at the Funnel. When I was doing the programming I did have a pretty clear idea of what I wanted to achieve. That was certainly an “ideal.” I was interested in film as a kind of radical area between what was cutting edge and daring about visual art and what was powerful about the movies. I liked the way visual art was inventive in its uses of materials and its incorporation of unexpected elements in order to say important things. And I liked the way that movies get at you emotionally with their “realism.” I still had a lot of belief in the idea of the avant-garde. I was interested in the ideals of some of the new feminist films being made at the time, the “New Talkies” they were called, and I did some programming using and referring to them. But frankly, I felt that some of them were better as theories than as films. However, it wasn’t enough for the organization to represent the ideals of one or two people. As an organization, the Funnel’s identity was too marginalized. To most people involved it rode on some hazy idea of being “alternative.” I see now that just wasn’t enough.

MH: The Funnel required an incredibly committed membership to ensure the organization could fulfill its ambitious program. There was a belief…

AG: Yes, there was. It wasn’t often articulated, however. Part of the belief was in a general sense of community, it was something to belong to. The Funnel had very little money with which it sponsored extensive activity and programming. Anything it accomplished it did on the backs of staff and volunteers who worked so fucking hard, myself included. When I was on staff in the early eighties my pay was $7,000 a year and I put in long hours — usually every day of the week. It was our dedication that allowed the place to exist. But it wasn’t sustainable. Even without the more philosophical and political difficulties it was grappling with, the Funnel just didn’t have the economic base to go on like that. It closed down after I had left it, so I don’t know all the final circumstances. From what I could see, it seemed to lose steam and slowly disintegrate.

MH: What has it meant not having it around?

AG: For me personally, it was a relief. When I stopped being the Director/Programmer I joined the Board for a while, but already it felt like the organization was in a rut. The same arguments and difficulties came up again and again. So I left altogether. When it finally closed a few years later, I was glad. In its last years it seemed to be digging itself deeper into a mess and I didn’t want that to be all that anyone remembered about it. In a bigger sense, its demise made room for LIFT and Pleasure Dome to develop.

MH: Okay, so let’s get back to your own work. How did Wound Close (8 min super-8 1982) begin?