Beginnings: an interview with Patrick Jenkins (April 2013)

Patrick: I grew up in Brantford Ontario, a small town. I went to high school in the early seventies and wanted to be a painter, a visual artist, that was my career track. But I seem to have had a strong interest in movies.

In those days there were two movie theatres in my town and films only came for a week. So you had to catch them on the first weekend or not at all. On Friday night I would go to the seven o’clock show, and stay in the theatre and watch the movie again at the nine o’clock show. The first screening was to enjoy the film; the second was to figure out how it was done. On Saturday night I would go to the other theatre and repeat this process. I thought this was completely normal behavior (Laughs) but it’s really an indication of how interested I was in movies.

At that time there were some fantastic films coming out of Hollywood, like “The French Connection,” “The Godfather, Part One and Two,” so there was a lot of great stuff to see at your local theatre!

This was way before there were DVDs, there weren’t even books available in town about how to make a film. I was obviously interested in movies as an art form, but had never thought of myself as a filmmaker.

When I went to York University in 1974 to study visual arts, I took some film courses. The only film production courses I could take, as a visual arts major, were in super 8 filmmaking. It was the medium I worked in for many years, from 1975 to 1982. In 1975, silver and oil prices rose sharply, so while 16mm had been affordable for the generation before me, all that had changed. I didn’t make a 16mm film until 1982, and I needed funding to do it. But super 8 was great, and with some help from these courses, I taught myself how to make films.

Up at York I met another student, Janet Sadel, who was putting together a super 8 distribution centre. There was a lot of excitement about super 8, especially among amateur filmmakers. There was an exciting festival dedicated to it at that time, the Toronto Super-8 Festival. It was the first time you could make movies with relatively little money. But the problem with super 8 was distribution, because unlike 16mm or 35mm, no one had projectors. You would have to send or take a projector along with the films in order to show them. Janet organized open screenings around the city, at Hart House for instance and the Ontario College of Art. I showed some of my films at these screenings.

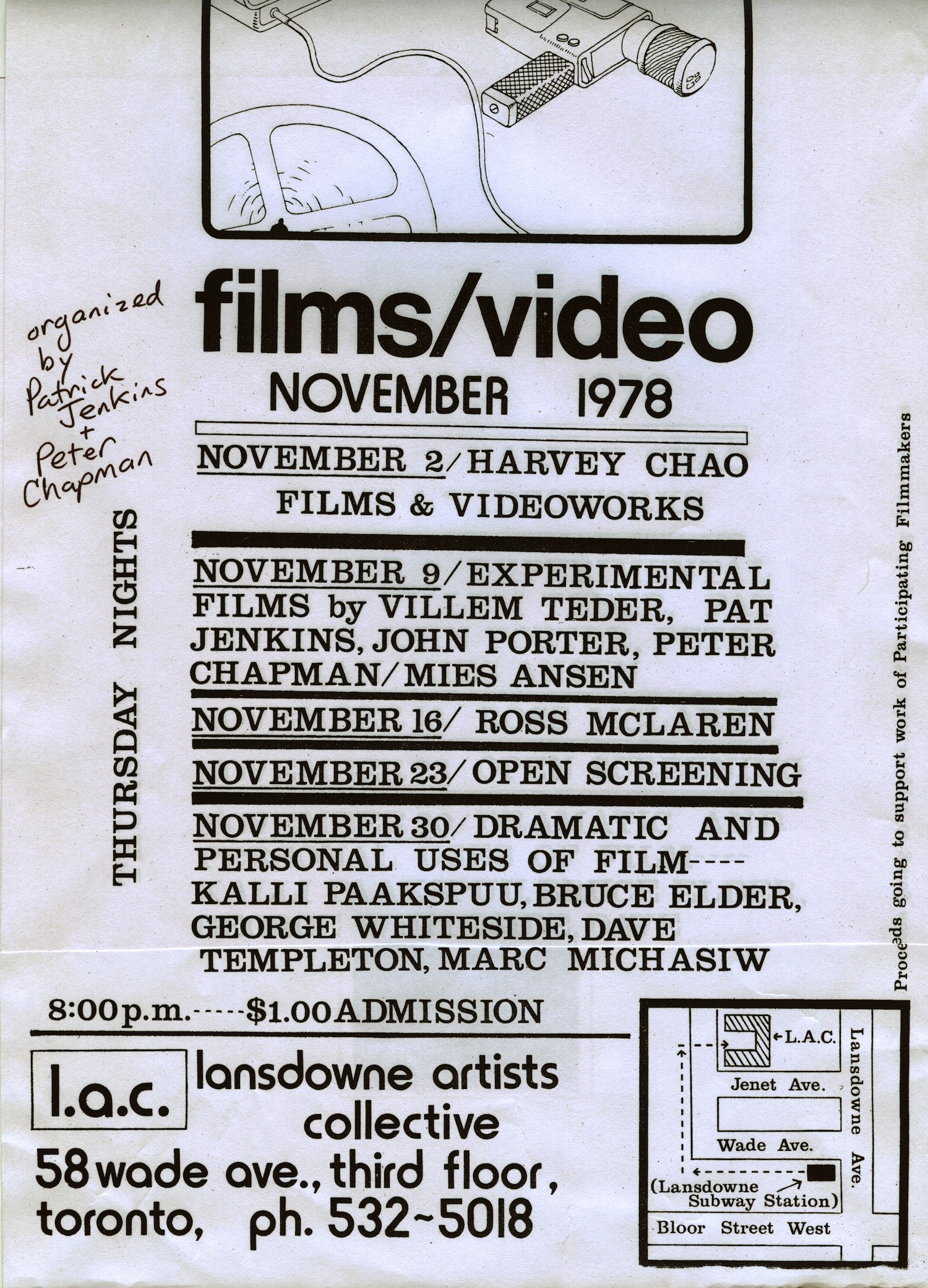

After graduating from York in 1978, I had a fifty-dollar a month studio at the Lansdowne Artists Collective building, and Peter Chapman (who I met through Janet) and I put together a four-night program of experimental movies in November 1978. Peter was working at a film lab, and interested in experimental art and music. He was an early Funnel member. We showed mainly experimental movies by local artists including Harvey Chao, Marc Michasiw, George Whiteside, Ross McLaren and others, plus an open screening and a mixed shorts program.

Mike: Was this the first time you met local artists?

Patrick: Yes, I had been at York University so I didn’t know a lot of people downtown. I did know a few people from my hometown, Dyan Marie and John McKinnon, who were studying at the Ontario College of Art at the time, so I did have some notion of what was going on, and I started lived downtown in September 1975.

But yes the problem with York University, located up there in North York, was that it wasn’t near anything! (Laughs) There were no galleries or art supply stores nearby. It was a commuter university. You commute up there and the rest of the world doesn’t exist. It took a while to make links downtown, but knowing some people going to the Ontario College of Art helped.

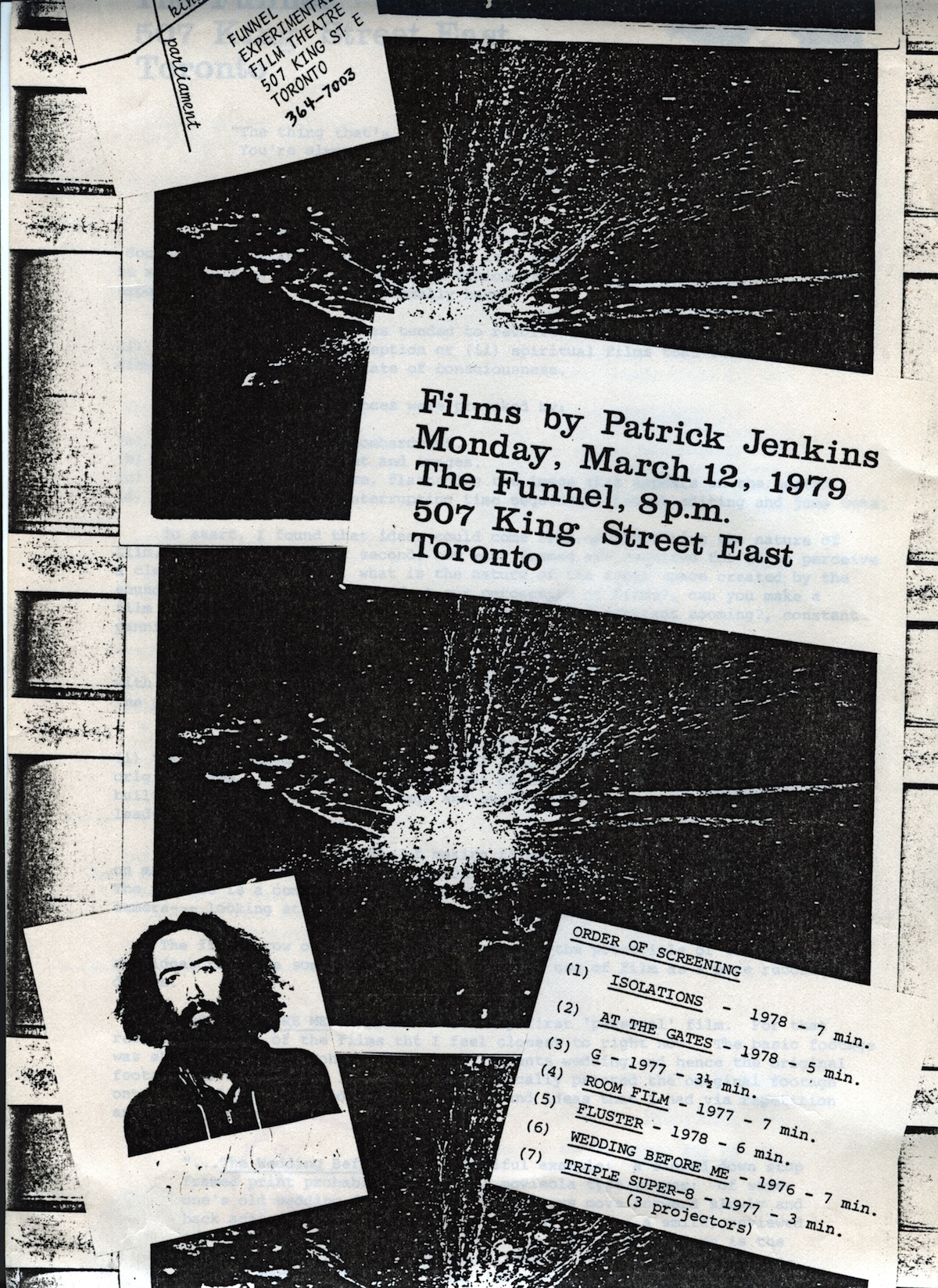

In January 1979 when the Funnel opened up on King Street I started going, and had a screening two months later, in March. The invitation to show came out of a casual discussion. Do you want to do a night of your films? From there I got involved as a member. As I recall the etiquette for becoming a member was that you had to hang out. And hang out. (Laughs) This used to drive some people nuts. But you had to hang out and get to know what was happening. Don’t forget this was a theatre that had been built from scratch, by a bunch of very dedicated people. I remember in the summer of 1979, I didn’t have a lot to do, I was unemployed, and so we built the office. The theatre was already built, but not the office. David Bennell was in charge of the construction. Adam Swica, Tom Urquhart, Peter Chapman, Frieder Hochheim, myself and a few other people would work a little each day, and it took us all summer on and off, to build it. It was all volunteer work of course.

There were two screenings a week, mainly by American and English filmmakers and us. Exhibition was the focus in those early days. I went to every screening, most members did. We were pretty dedicated. It felt like catching up because we hadn’t been able to see these films. You could finally see the work you’d read about for years, trying to imagine what it might be like by reading descriptions in books and looking at stills. These screenings gave us the lay of the land, for better or worse. I liked Fellini a lot, as well as Surrealism and the films of Maya Deren, and I thought experimental film leaned in that direction. Little did I realize, that wasn’t the case! (Laughs)

The work of the artists involved at the Funnel was completely diverse. We were not a school or a movement or a style. My approach was unique, as was everyone else’s. We were a bunch of people making something that seemed experimental, and were keen to see work from around the world.

It was a challenging time to be an artist with my interests in the late seventies. Performance Art was all the rage. Punk had arrived and some punks were very anti-art. They hated experimental film. Sure they liked Ross McLaren’s Crash ‘n’ Burn and Suzanne Naughton’s movies, but those were punk films. Occasionally punks would come and yell at the screen. I liked punk to a degree, I liked its energy, but I was more interested in the music than the look. I wasn’t going to go around acting like a jerk. I’m not that kind of person. (Laughs) The Funnel membership weren’t punks. Punk could often be very conservative. It was three chords, basic music and anti-art. I liked art.

Secondly, although super-8 film was not considered a serious artistic medium, not even by visual artists, we were excited about having a theatre we could show our super-8 work in. At the Funnel super-8 was treated as a legitimate art form, and they had a good projector. But there was a feeling, in the larger art community, that we should be making video art not film, because film was seen as dying. There were very strong opinions. Video was the contemporary medium of artists, while film was seen as an expensive and old-fashioned way to do things. There was a real split between the film and video community, there was some crossover, but we didn’t show a lot of video at the Funnel.

Until New Image Painting came in painting, even working with images was a “no no.” We were still in a hugely conceptual art phase. I guess film got around that because you didn’t draw it, a lot of conceptual artists had been working with film. I was from a mid-boomer generation that decided we’d had enough of conceptualism. I felt that conceptual art was a hangover, a response to the Sixties. The Sixties had been this great time of experimentation, and conceptual art arrived to straighten things out. (Laughs) They were going to de-commodify the art object, de-materialize it, get back to concept, and get away from the art market. I remember going to art school and the instruction was: no drawing, no painting.Of course art comes out of where you live and who you are, not from being told to do things a certain way, so eventually my generation decided to get back to working with images.

Experimental film was not considered cool either. It was considered another generation’s thing, a 60s thing. Those were my impressions. What was cool was new narrative. When Scott and Beth B came up from New York, of course they were tied to the punk and new wave movements, and the theatre sold out. This was the new generation; their films were decidedly not experimental in relation to experimental film history. Structural–materialism was where experimental film had been, films examining the nature of film. The work of the Bs were almost homages to film noir, returning to narrative. I felt like they were anthropological films, documenting the No Wave artists who starred in them. That’s when the visual arts community came to the Funnel, to see the Bs.

I think one of the handicaps with the Funnel was its location. It was in an area of town where there were very few other arts groups. That set up a remoteness to the rest of the arts community. I’m not criticizing the decision on where to locate the theatre, because I’m sure it was a challenge to find a space that was big enough and suitable for a theatre. But boy you had to be dedicated to go to a screening, especially during the winter. Back then it was really cold on those winter nights. (Laughs) In that neighbourhood on King Street East near Parliament, streetcars ran infrequently on Friday nights and there weren’t many people around. It was kinda eerie. (Laughs) If I missed a streetcar, I would walk to Yonge Street to the King Subway Station, which is a fair hike, and not see another streetcar along the way.

There were a lot of memorable screenings. One that stands out in my mind is when James Benning showed his feature “Him and Me”. I didn’t like the film initially, but it stuck in my mind, and after watching it a few more times, I got really excited about the direction Benning was going, incorporating narrative and personal biography into his films, which prior to that had been more formal. My filmmaking didn’t evolve at all in this direction, but I thought Benning was an interesting filmmaker, trying to bring elements of life back into experimental film. Also he was very articulate. In the Q & A after his screenings he would talk about mathematics and the social work job he had done earlier in his life and how that influenced his filmmaking. Really cool!

Eventually I was trying to get my films shown and approached curators in different cities who were interested in showing me only as part of a Funnel package. As much as I loved a lot of things the Funnel was doing, I felt I was being too identified with it. I was being defined as just a part of it. I’m not really a group person (Laughs) and as an artist that’s always a struggle, because you’re always looking for freedom, you don’t want to be tagged that way, as just part of a group. You have your own path. It’s fine if as an artist, you’ve agreed to make art collectively, with other artists, but my interest at the Funnel was in watching films and exhibiting my work. I didn’t see the Funnel as a collective aesthetically or conceptually; we were all individuals, who each made their own work in their own way.

I was making my work independently in my studio. I wanted to be recognized as an independent artist, not solely as a member of an organization. I left after three years because I wanted to get some distance. I had had a lot of great experiences at Funnel, but I felt I needed to go my own way. About this time, in 1983 or so, I felt that the field of experimental film was too narrow for my interests; it didn’t contain all that I needed. It was supposed to be about freedom, but there was so much I couldn’t explore. I was interested in a lot of other things like humour, storytelling, music, science fiction, novels, illustration, painting, but I couldn’t figure out how to grow in experimental film. Also, I didn’t like the fact that a lot of people had a very antagonistic attitude towards experimental film. When I would tell people I was an experimental filmmaker, quite often they would tell me immediately how much they hated experimental film. That was a hard attitude to work around. A lot of people I met saw experimental film as something that was going to bore and torture them. They hadn’t seen my films, they had just had a bad experience with experimental film and didn’t want to repeat that. To have an audience that is convinced it will be bored before they even see the films was a tough attitude to deal with. I had made the films with joy and enthusiasm, to expand what a film was, not to torture or bore people. (laughs) Luckily I found a way out!

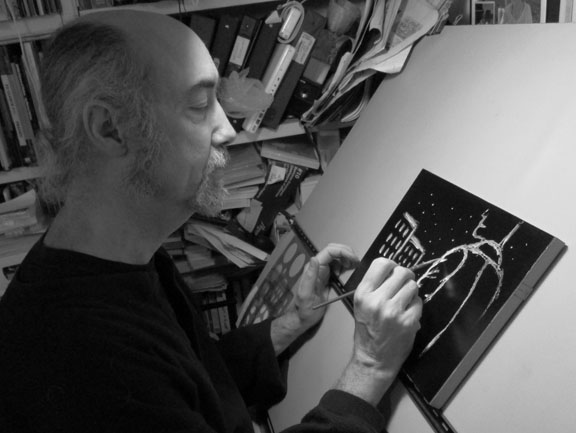

I’d been doing single frame shooting and animation work in my films without thinking of it as animation. Around that time I was asked to teach animation workshops for children, which was a great experience. I thought maybe I should go further in this direction, and as I gradually moved into animation I felt I was entering a bigger arena. It seemed to me that experimental film had a very distinct history. The sixties had seen a great renaissance, a golden age, and experimental filmmakers from that era had become sacred: Brakhage, Snow, etc. Those names are still revered to this day. As a young person I didn’t feel there was a place for me in experimental film because there was a strong notion going around that, right or wrong, everything that could be done in experimental film, had already been done by these filmmakers in the 60’s.

But with animation, a larger world started opening up to me!

Wedding Before Me (1976) was my first film, made in a York film production class. It was made from my parent’s wedding film, regular-8 footage from 1953. I borrowed a little piece of ground glass and a super-8 movie camera from the school, rented a projector that could project freeze frames for the weekend, and reshot the film a frame at a time. The projector was advanced one frame, and then I’d shoot one frame with the camera. I was analyzing the original film, bringing out events I thought were a little bizarre. It was striking to see my relatives appear so loose and youthful; they’re having fun, right? It was very well documented by my uncle who had never shot anything before, and when I saw the films he shot later there was nothing approaching this one.

Just as the original film winds up another uncle of mine, a real character; enters the frame to kiss my mother. He sticks his tongue out just before he does it and she just reels away from him. I repeated this motion and slowed it down, looking at the little gestures and the kiss between them. Is it a real kiss? These are the questions the film poses. There was one moment where the veil blows over my mother’s head, which was neat if you slowed it down and looked at it. Some events aren’t so visible in real time, only when they’re slowed down. I don’t regard the film as biographical; instead it reveals the idiosyncratic moments in the original footage.

Mike: It was a very sophisticated way to work.

Patrick: Yeah, I had heard that you could re-photograph films with a camera. I gave it a shot. When you’re young, you’ll try anything. It looked really cool, like the film was going to lose control at any moment. (Laughs)

Wedding Before Me was a great experience and it was shown all over the place. I realized quite quickly that I could change the way I made movies quite radically between films. I could decide what experience I wanted to have making the film. Subsequent films used a totally different approach and technique.

Mike: You won an award for best experimental film at the Toronto Super-8 Film Festival for an early movie called Fluster (1978). Can you talk about making it?

Patrick: Yeah, a lot of my films were shown at the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival. It was a blast. There was a lot of excitement about super 8 especially among amateur filmmakers. I used to go to it all the time and see all the screenings. Wedding Before Me was shown there and yes, Fluster won a prize.

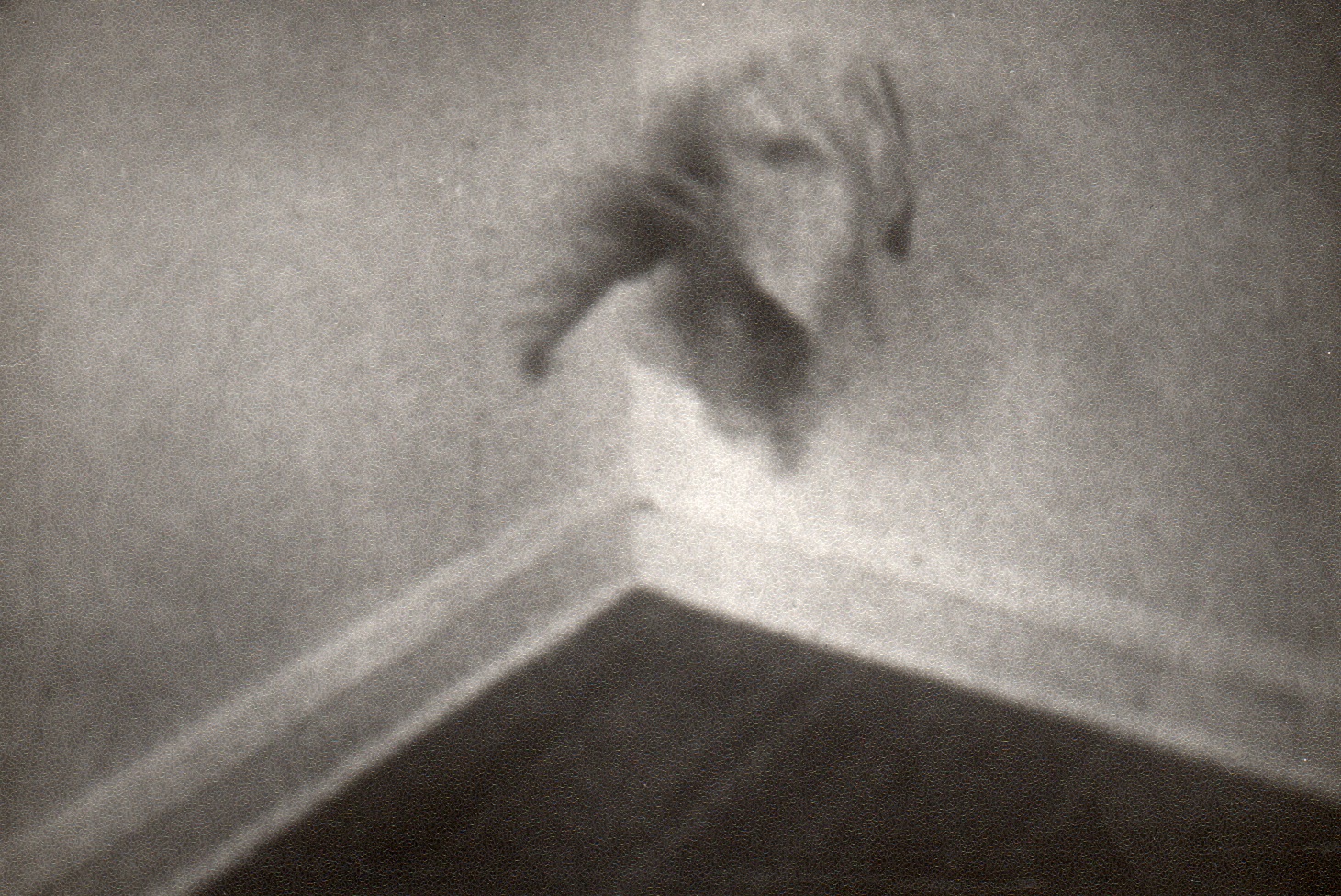

Fluster was more or less the next major film I did. I wanted to shoot something in black and white. I think that stock had just become available in super 8. It was inspired by the classic Surrealist films, which I loved. Friends of mine were living as tenants in a huge, empty, Victorian mansion, in Paris, Ontario. The top floor rooms were completely empty, no furniture, nothing, and that allowed my imagination to run wild. (Laughs). It’s a silent film, so your thoughts make up the soundtrack, and the camera careens through the rooms, point of view style, as if someone is frantically searching for something in all these empty rooms. One key image in the film is a bed sheet that I would toss into an otherwise empty room and take single frame shots of before it hit the floor. I remember throwing that sheet over and over again. (Laughs) When the film runs the sheet looks like a ghost, some enigma that is rapidly fluctuating, like a manic cloud or unknown being.

I guess there was some controversy among the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival jurors that year about whether the film deserved a prize. Jana Sterbak, now a well-known Canadian visual artist, was on the jury and defended it. That was nice of her, I really appreciated that.

There was disagreement between the Funnel and the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival about the paying of artist fees for showing the films, which the Festival did not do. At that time there was a movement that insisted artists should be paid when their work is shown. That struggle continues to this day, and a lot of festivals still don’t pay fees for showing films.

Blaine Allan, in an article on Funnel, mentioned something about my showing my films at the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival being against the artist fee policy at the Funnel. I disagree with that. I agree that artists should be paid, but I’m free to show my work where I like, and anyway, I hadn’t agreed to any Funnel policy about the Festival. I was glad the Festival was showing my work. I had shown work at the Festival before I joined Funnel, I won the prize for Fluster just as I became a member.

So in Fluster, I was shooting live action, and then I would turn to single frame shooting if I wanted to achieve some effect. I didn’t make a distinction between those two ways of making films. I don’t know why. It seemed completely normal to me. (Laughs) When I drifted into animation it wasn’t a huge leap because I’d already been doing it in my experimental films.

After that I made a few other films. Ruse (1980) was a poetic film I shot in a house I lived in, in Toronto. I would capture how the light fell in some of the rooms at different parts of the day and film tiny details of objects in the house with a macro lens so they filled the screen.

After that I made a longer 20-minute silent film called A Sense Of Spatial Organization (1980), which was like an ersatz science film. (Laughs) I was serious though. (Laughs) The concept was, what if all the elements we use to talk about reality — time, colour, space, perspective, distance, measuring — could actually be isolated? I tried to do that creating little filmic situations where you can see the ironies of perception. At one point we see my hands drawing and measuring a two inch line that spans across the frame with a ruler and writing down the distance, which of course is totally wrong, because the projected image of the film is much larger than two inches. It was a fun film to make. People would laugh along with it, because it had fun with how we perceive and measure reality.

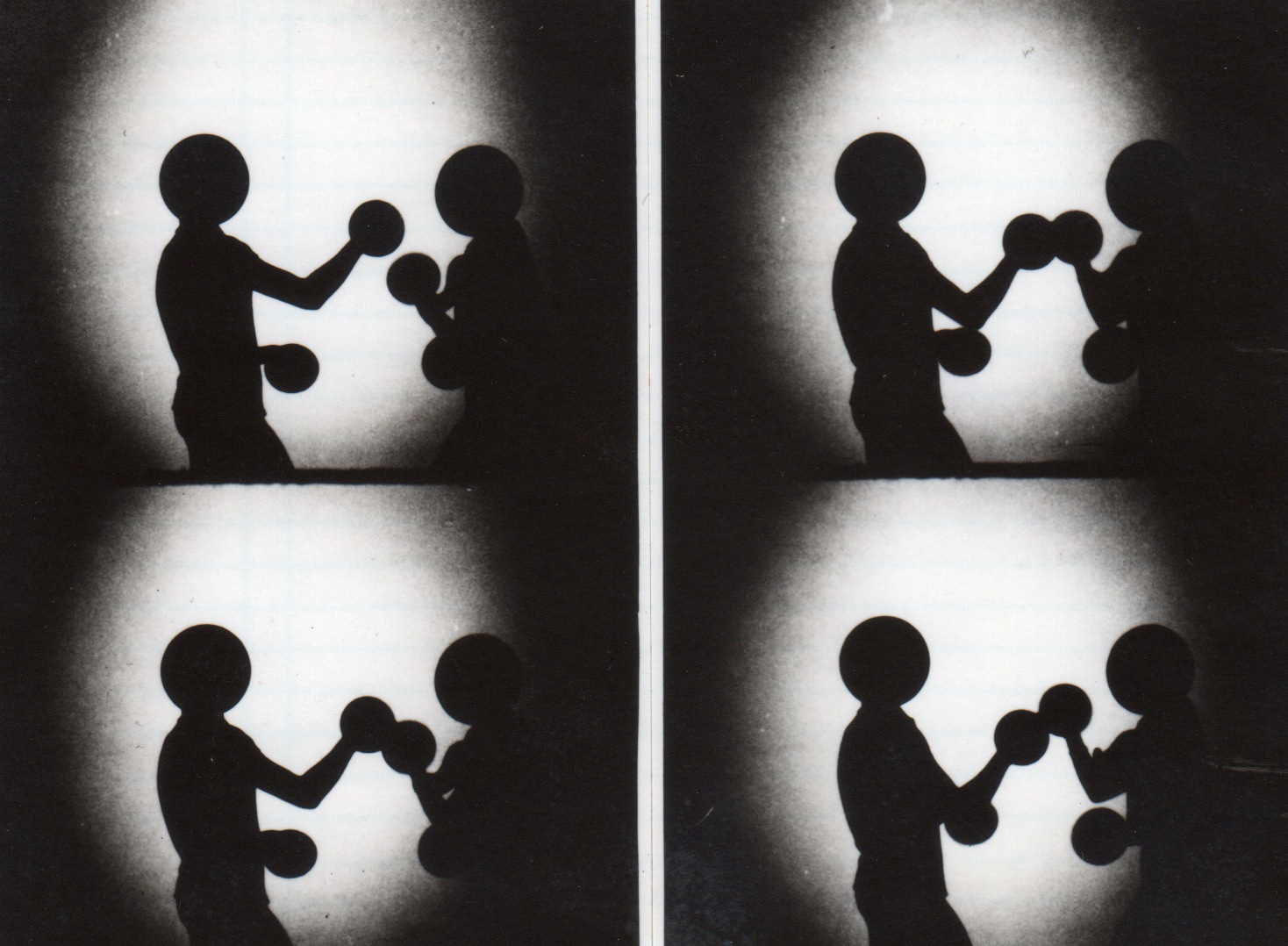

Then I got interested in shadows, (Laughs) and my next two films, Shadowplay (1981) and Sign Language (1982), were about that.

In Shadowplay, all the imagery appears as backlit shadows projected on a translucent screen like a Balinese shadow puppet play. It was a cool film to make. There isn’t a narrative to it per se, but there is a visual logic. It’s about reducing imagery to silhouettes, to their essences. At one screening, an audience member said that it was like the allegory of Plato’s cave, where all the deluded people in the cave are seeing not reality but only shadows projected on the cave wall from the real world outside the cave. Interesting interpretation! (Laughs) I was just playing around with representation! New image painting had come in and I, like other artists, was exploring how to depict images of the world, and what our method of depiction said about the world. Also there was a joy to be finally able to work with images again.

Sign Language, my first film in 16mm, followed that. It was more political in nature. At that time, symbol signs, such as stick figures to indicate male and female washrooms, were replacing words to make it easier for people who speak a variety of languages to be able to navigate through airports, etc., because everything was depicted as a symbol and didn’t rely on knowing a specific, written language. It was fascinating how designers could reduce things down to a few graphic shapes to become a symbol of, for instance, a drinking fountain, washroom facilities, or customs officers. However I was suspicious of this level of reduction in visual depiction. It seemed to depict the world in a succinct but ultimately bland way, lacking nuance. So I took that notion of reduction to an absurd degree, depicting bombs falling, earthquakes etc., in a highly reduced, cartoonish manner. That investigation and critique continues to this day in my work in animation. Animation tends to reduce and stylize depictions of humans to convey their essence, but oftentimes I wonder if the nuances of what we deal with in life are being shaved off for a laugh.

I toured my films a lot, mainly to artists-run centres. At first I used to take a super 8 projector on the plane with me. Then I realized that I had to blow up my films to 16mm if I wanted any serious distribution, so that’s what I did.

I showed my films all over the place, at Millennium Film Forum in New York City; Pasadena Film Forum, Pasadena, U.S.A.; Open Space Gallery, Victoria, B.C.; Tyneside Cinema, Tyneside, U.K., Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, to name a few. The best thing was showing them on WNED Channel 17 TV, a PBS station out of Buffalo, N.Y. that showed a program called “The Frontier.” A lot of people saw my work on that show!

Mike: You’ve taken your early experimentalist work out of distribution, is that because you feel they don’t represent who you are as an artist?

Patrick: Well I think it was in the mid-90’s that you mentioned to me that Cinematheque Quebecoise in Montreal was open to archiving work by Canadian experimental filmmakers. That was great. I was concerned that my film prints were fading. They had been sitting at my distributors for years in less than ideal conditions and hadn’t be rented or screened in a long time.

By that point, I hadn’t made an experimental film in a long time. I had been doing work in independent animation for about a decade by then. There was only one release print of each film so I decided to put them into safe keeping at the Cinematheque to preserve them.

I was feeling a little discouraged by experimental film. As I mentioned before, I didn’t feel like there was a place for me in experimental film and that I hadn’t been able to achieve much in it. By then I had moved on to do work in independent animation, which continues to this day.