Mike: I’ll never forget the first time I met David McIntosh, the Funnel’s director for the longest two years in recorded history, during the mid-1980s. It was at a job interview that was done Funnel-style, meaning that all thirty “core” members were on hand to size up and interrogate the outsider. Previous directors had been drawn from the family, this was the first time the club was stepping outside of the bloodlines, and there was apprehension and excitement. When David stepped into the room thirty people fell silent as we looked him over like a rare zoo specimen. He might have bowed. He was funny and well spoken and so smart that eight syllable adverbs kept falling out of his faux leopard skin suit jacket. I kept worrying that at any moment he was going to wise up to the fact that he didn’t belong here. He was too smart and beautiful to be ready for his Funnel close-up, and the longer the interview went on, the more I had the sense that he was interviewing us. Would he find the bride acceptable? After a final lunatic question about corporate fundraising was broached (Corporate? Fundraising? At the Funnel?) David replied, “I believe new forms of capital reinvestment require skills involving cocktails and blowjobs, and I’m excellent at both.” There might have been other candidates, I can’t remember now, but it was clear as soon as he left the room that a new director had found us.

David: The majority of the memories I have of the Funnel are largely unprocessed, and I think that’s because the Funnel was and is indigestible. In fact, I think a lot of people at the time — mostly Toronto people — were kind of afraid of the Funnel. It was not for the faint of heart. It was no cutesy ‘free to be you and me,’ left liberal, warm and fuzzy, struggling artists playpen. This was an unruly and unpredictable collective where the fight against corporate, industrial, mass-produced representation was constant and fierce. Funnel people would fight for days — what am I saying, for years! — over the relative radicality of a dissolve versus a cut. Long before the current round of multimedia vertical integration and corporate concentration, the Funnel had a clear and insistent counter-cultural mission, an integrated concept-to-consumption vision of experimental film that included production, distribution, exhibition, publication and training workshops. With minimal financial resources, but a surfeit of collective energy and motivation rarely seen in the maturing artist-run centre culture of the period, the Funnel presented twice weekly film screenings, maintained a collection of films for distribution, operated an extensive equipment access program including optical printing and film processing equipment, held regular public film production workshops, and published newsletters with original critical texts, along with several series of catalogues of curated series. And the Funnel was multi-disciplinary, obviously presenting film screenings, but also performances, video, sculpture/installations and painting exhibitions. This was the place where established artists like Joyce Wieland and Michael Snow worked, and where artists like John Greyson and Jane Siberry made their first films. The Funnel had an enviable international reputation, hosting artists from around the world. In short, it was a site of enormous energy and accomplishment, all managed on a shoestring budget and seemingly endless volunteer energy.

Nonetheless, people in Toronto didn’t know quite what to do with the Funnel. It remained a sort of ‘odd man out,’ ‘from the wrong side of the tracks,’ isolated in many ways. It was not part of the Queen Street scene of the 1980s, being located on King Street East near Eastern Avenue, a decidedly unhip hood at the time. And it was shunned conceptually by prevailing art mavens of the time. A perfect example of this positioning of the Funnel in the Toronto scene was the Jack Smith performance, a week of nightly presentations of his new work for the Funnel, ‘Brassieres of Uranus.’ I basically produced the event, and even performed in it as a worker in Jack’s ‘Brassiere Museum,’ wearing a black leotard and a pair of upholstered flowerpots strapped to my ass to exaggerate my buttocks, Jack’s erotic obsession at the time. (A quick Jack moment. I was working on getting props together for his performance when he came into my office holding a muffin tin on his ass, and asked me, ‘Do you find this erotic?’ And I kind of did. It was like forty small buttocks on his ass.) Virtually no one from the Queen West art scene attended any of Jack’s performances. Joyce Wieland and Michael Snow were regulars in the audience, and a couple of people like Martin Heath and Gordon W. joined in the performance, but that was it. A couple of decades later, a number of Toronto curators finally began showing Jack’s work and acknowledging his position in art history, yet Jack’s performance work at the Funnel remained undigested, perhaps indigestible, and unmentionable for them.

During the period I was involved in the Funnel, it was fully engaged with the shifting ground of experimental film work, largely focused on negotiating the relationship between structural cinema and gender. The Funnel was a focus for groundbreaking international women’s work including films by Marguerite Duras and Sally Potter, as well as queer culture. Kenneth Anger, Warhol Superstar Ondine, the queer Kuchar brothers, Barbara Hammer, Bruce LaBruce and GB Jones all contributed to the building of an oppositional queer critical mass at the Funnel. At one point, the staff of the Funnel was all gay, including Midi Onodera, George Groshaw and myself.

Despite this intense and irrepressible creative energy and active engagement with emerging art practices and cultures, the Funnel had what turned out to be a fatal flaw, what I now think of as the ‘membership has its privileges’ problem. Funnel membership was hierarchical, with some members having more power than others, a decidedly undemocratic structure. Efforts to change this structure into a more evenly distributed system of power for members of the collective failed however, and the Funnel began a slide into irrelevance. A sad loss really.

April 2012

Resistance: an interview with David McIntosh (August 28, 2013)

Mike: You worked as the Funnel’s director from June 1984 to March 1986. How did you get hired?

David: I submitted an application and was invited for an interview, I must have seen a notice somewhere. I didn’t know anyone at the Funnel before I walked into the door. I had been working at the Canadian Film Institute in an office on Yonge Street, a few blocks south of Bloor upstairs from a commercial cinema. I was working with Pat Crawley, he was the director of the film program at Algonquin College which is where I’d been before that. In 1982 we got hired to determine the impact of computers on the film industry in Canada. People didn’t even have computers then, the first desktops didn’t appear until 1984. We were working with word processing units and trying to figure out what this was all about. That project came to an end and I was looking for work. Then I found out about this job at the Funnel. Were you at the interview?

Mike: Every member was asked to come to the Funnel, but as you were the only one interviewed, I assumed that a pre-selection round had already happened. There must have been forty people in the room waiting for your arrival, a forbidding and intimidating scrum. I’m sorry to hear this was your first impression of the Funnel.

David: Everyone sat in a circle around the room in those uncomfortable chairs. I remember being really cold, it must have been winter. We all sat with our coats on.

Mike: Heating was usually reserved for screening nights.

David: I remember a question that Ross McLaren might have asked me: “What do you think about pay television and its impact on film?” I said that all of this pay-TV stuff “is going to crash and burn.” Crash ‘n’ Burn was the first punk club in Toronto as well as the name of Ross’s film about the club.

Mike: Did you have an overlap with outgoing Funnel director Michaelle McLean?

David: I don’t remember an overlap, but Michaelle, Anna Gronau and Ross were very involved in bringing me up to speed. Midi was already there and she was very helpful.

Mike: Can you talk about the Censor Board protocol?

David: When I got there the Funnel had already been targeted and temporarily shut down for renovations, that was part of the ancient history. In order to keep operating the theatre and having public screenings we filled out forms for every film that was screened, and these would be sent to the Board who would grant “prior approval.” The process was called “approval by submission.” Other artist-run centres refused to submit to the prior approval process.

We worked with a number of individuals and groups like OFAVAS (Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society) which was a coordinating body that took the Censor Board to court. We participated in a number of community events, including an OFAVAS fundraiser at the Mirvish Theatre. Jackie Burroughs was a great supporter of the Funnel, she came and read from the Maryse Holder letters which became her feature film A Winter Tan.

Mike: Did you feel heat from other groups who wanted the Funnel to take a harder line against the Censor Board?

David: I think that was always there. The video-based artist-run centres didn’t submit to the prior approval process. There was a certain degree of questioning about continuing to submit to this process. But that was what the collective at the Funnel had decided to do, it was the procedure for staying open. I saw more plainclothes cops at video screenings where they didn’t submit to the Board than at the Funnel. The Funnel audiences were pretty loyal audiences so you knew who was there. John Greyson and I used to go to video screenings at A Space or Vtape and pick out the cops. They didn’t show up at the Funnel, but they did surveil a lot of the video screenings to see what was going on. There was a certain amount of questioning about the two positions in relation to public screenings, but there was also a lot of coordination, there was never any wall between us. Now that’s from my perspective, the view of people on the ground might have been very different.

Christina Ritchie curated a program of video called Signal Approach that had a catalogue and critical essay attached. She was working at Art Metropole at the time. There were limits to our ability to bring people into video screenings given the Funnel’s chosen relationship to the Censor Board. The Funnel was submitting documentation for everything shown to the Board, but the video community steered clear, and took a position of non-submission.

Mike: Which meant that the Funnel couldn’t show many local video artists because they wouldn’t allow their work to go to the Censor Board.

David: Exactly.

Mike: Was there any push from inside the Funnel to re-open the debate about how the Censor Board would be dealt with?

David: No. It was a constant given that nobody wanted to do this but we wanted to stay open, especially after everyone had spent all that time and effort to bring the building up to code to stay open.

Mike: In 1981, prompted by the Funnel’s anti-censorship stance, city inspectors visited the theatre and demanded a $35,000 upgrade in the facilities. A great volunteerism effort created a firewall around the space, and allowed the theatre to open again in the fall.

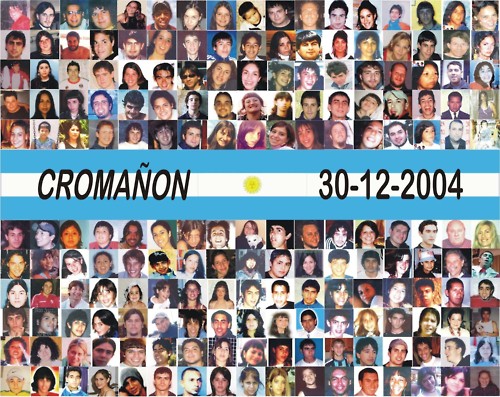

David: What happened at the Funnel remonds me of another situation. I spend a lot of time in Argentina now. On December 30, 2004, there was a devastating fire in the Cromañón nightclub in Buenos Aires, and 194 people were killed. They died because of poor exits and bad construction, the result was a clampdown on public spaces. In a city where it’s very expensive to set things up, effervescent cultural activities often occupy temporary spaces, but after the fire that became impossible. Likewise, I think part of the intention of the provincial Censor Board here was to shut down unregulated spaces.

One of the important movements in that period was women working against censorship. Anna Gronau was part of a group that took the Censor Board to court, Judith Doyle published a history of censorship in the province, and there were also others working outside the Funnel including Lisa Steele, Varda Burstyn and Carol Vance. There was a collaborative effort to try to understand why this was happening. We came to the conclusion that censorship wasn’t about protecting the public, it was about shutting down independent, non-traditional voices. The obvious targets were women who wanted to express themselves in an overtly sexual way, and the queer community.

These community efforts to establish the larger motives of censorship gave the Funnel a lot of strength to try and see beyond the immediate, day-to-day, we’ve got to fill out this oppressive form and submit it to prior approval. The Board never asked to see anything we screend, it was all done by paper. They retained the right to ask to see films, but I don’t remember them asking. And you learned how to describe movies in the forms. You didn’t write: “includes shots of full penetration.”

“No meat hooks in vaginas” was Mary Brown’s rallying cry. She was the public face of the Censor Board and tried to galvanize public opinion. There were fingers missing from one of her hands, we used to say they were lost in a fit of cutting films. Her big issue was snuff films. For her, the Censor Board was there to protect the public from snuff films, women with meat hooks in their vaginas was her quotable quote, though nobody ever saw this material. That was an interesting counterpoint to the anti-censorship movement that took a very different perspective on gender and representation. Most experimental work that was sexually explicit tended to be critical of commercial cinema in all of its expressions, from Hollywood love stories to porn. People interested in reshaping the representations of gender and sexuality were caught, and again this was largely women and queers.

Mike: There was a moment when you were the director, Midi was the equipment manager and George Groshaw was the office manager. The entire office staff was gay, do you think the Funnel was a queer space?

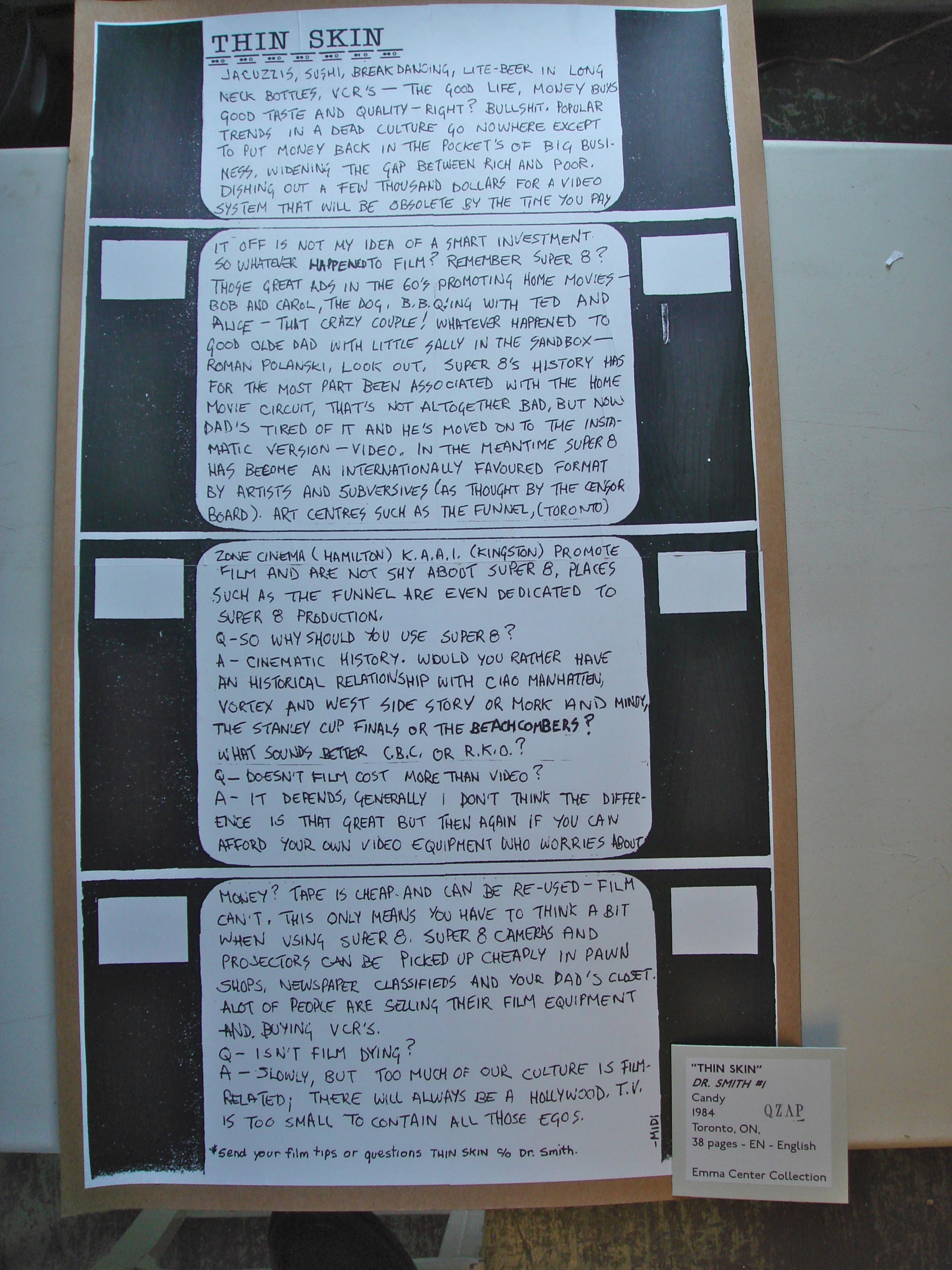

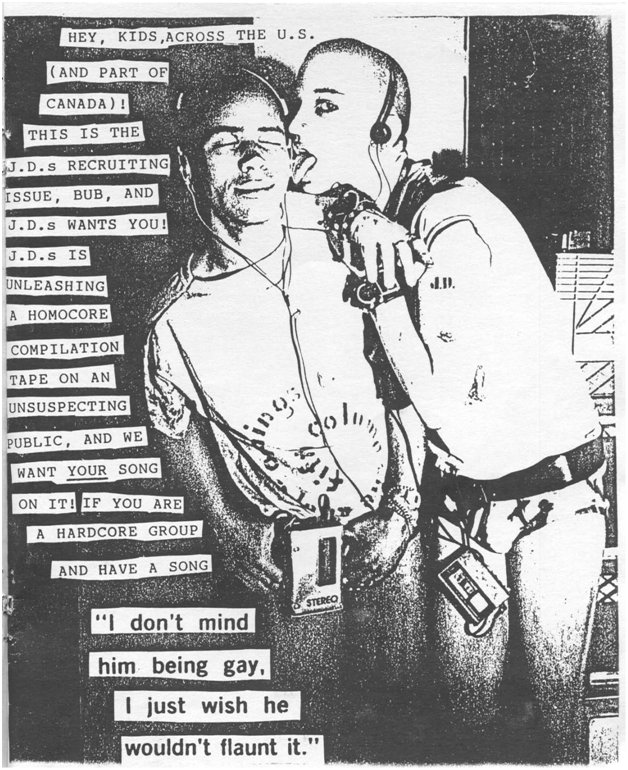

David: What is a queer space? We’re everywhere! No, I wouldn’t call it a queer space, but it wasn’t anti-queer either. When you look at the membership at the time, the core members of the Funnel weren’t overtly queer at any level. But that being said it was a place where gay and lesbian and trans-gendered artists brought their work. John Greyson made his first film at the Funnel. Bruce La Bruce showed his earliest films. There was a lot of space at the Funnel for people to do things and some of it was queer. Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones put out a zine called J.D.’s. Midi and Jean Young and Candy Pauker did a zine called Dr. Smith which wasn’t a Funnel publication, but the Funnel was where they all hung out. It was their club. The presence of queer artists at the Funnel during that period was remarkable. Kenneth Anger came, and Warhol Superstar Ondine was there regularly. I don’t think it was an overtly queer space, but in the pre-HIV, early eighties, queer culture lived outside of the mainstream.

Mike: This was before a million people began showing up for Pride week.

David: Absolutely. To engage publically with queer culture meant working outside the mainstream. It’s hard to think of queer films from that time, other than the odd Hollywood horror film like Cruising (1980), where queers were psychopathic murderers or murder victims. We hosted Jack Smith, Tom Chomont and Mike Kuchar. We could make a complete list but it’s almost like retro-projecting a notion of queer space onto the past. I don’t think there were any queer spaces in the city except for a few bars and bathhouses.

To give that comment a bit of context, I moved to Toronto in 1980 and the bathhouse raids happened a year later. (On February 5 1981, 150 Toronto police officers did a midnight raid at Club Baths, the Romans II Health And Recreation Spa, the Richmond Street Health Emporium and the Barracks, arresting 286 men.) The raids were formative for the queer community. In the ensuing demonstrations I was on the lines with thousands of other queers in what was basically a riot on Yonge Street. Harry Sutherland made a film about this moment called Track Two (1982). He had started shooting around the hustler track in the Church and Isabella area, and then the raids happened and it became a whole other production. That was one of the earliest works that showed collective consciousness in the gay/lesbian community, and this was a moment of radical change. I think the Funnel connected with that moment, even though it wasn’t overtly queer. It’s interesting to think about the historical context. That was also the beginning of the entrenchment of conservative politics in Canada, which we’re still living through now. It was the beginning of the Brian Mulroney era, when things started tightening up…

Mike: You’re suggesting the mainstream political reaction shot to the on-the-ground liberation movements was a conservative backlash.

David: Yes, it was the establishment’s way of pushing back, and as a result funding started disappearing, and the Canada Council had its wings clipped. The Canada Council was central to the artist-run centre project across the country.

When we look back at the early eighties we can see that queer space was just starting to assert itself publically. There were new and emerging forms of self-representation in experimental film and video, there was the queer-oriented painter’s collective that Andy Fabo was part of, ChromaZone. Despite the fact that the Funnel was located in the east end nowhereland, it did have a serious queer community engagement.

Chromazone collective [l to r] Hans Peter Marti, Oliver Girling, Tony Wilson, Rae Johnson, Andy Fabo. Sybil Goldstein (photo by Hans Peter Marti, 1983)

David: I don’t see myself fitting into any sort of modernist project, but I can speak in utopian perhaps. I think people at the Funnel really did believe that we will do this work and we will prevail. That one day people would wake up and say Julia Robert’s films suck, I want to go and see a Michael Snow movie. I think we really believed we were changing the core of representation. It was a project of radical social change through representation.

Why did people engage in structural cinema at all? In part it was to get out of Teresa De Lauretis’s gendered apparatus of cinema, to get out of that positioning of the self in relation to the apparatus. If you read Malcolm LeGrice, his notion of structural cinema is that you take up and deconstruct the apparatus and transform it into content, a light bulb on in a room for ten days is a work of structural cinema, a work of light and time. The intent was to have an active audience, to escape the suspension of disbelief and bring into awareness a whole set of industrial relationships that underpin traditional cinema. Potentially, there is a utopic moment of liberation when the active viewer participates in the co-construction of meaning. As opposed to industrial cinema where you lie back, it washes over you and you leave. You have to be passive to be part of that structure.

I think we understand it better now that we have distributive technologies like the internet. One of the things that still resonates for me about the Funnel was its insistence that everyone could make a film. The aim was to get the technology into as many people’s hands as possible. This was also one of the conclusions we arrived at in the CFI project about the potential impact of computers on film. If you get technology into everybody’s hands, that will produce innovation. Now there’s a word that has undergone changes over the years. In the mid-eighties, innovation was about radical social change, now it’s about what product you can contribute to Google. It’s interesting to think about that element of the utopian construction of the Funnel. People did believe. I remember Jim Anderson making a film where he taped seeds to clear leader and tried to get it to go through the projector. It was a failed experiment but a beautiful one. He made a film with no money that aimed for a more direct relationship between representation and materiality. That’s what everybody was doing in their own way. There might have been a shared history of cinematic avant-gardes that we had in common, but we insisted on a distributed power. You put the tools into as many hands as possible and have a dialogue with experimental cinema and push it somewhere else. This was a point of time when people were trying to move away from what they called the blob films to more narrative work. Blob meaning colour field, abstract, chemical films.

Mike: Could you make the link between the Funnel’s hope for activated viewers, the viewer-as-artist, to societal change? Was the space of the theatre a picture of what that change could look like, a gathering of separate but equal co-creators, everyone sharing a dream of light, but living it in their own way?

David: This is really tricky territory because that was the core understanding of everyone at the Funnel. More voices were better, let a thousand voices speak. We were always trying to bring more people in. As you know that project failed, the Funnel died over that. But the idea was simple: the more people that can self-represent, the more we are liberated from the requirements of industrial cinema and its capitalist underpinnings. If you put technology into people’s hands they will self-determine how and what they will say. This is very different from other models of vanguard movements where a core group of people lead the way, and when everyone else realizes the error of their ways they get on board and you have a revolution. This is the core vanguard model of political revolution that occurred in places like Cuba. But it was superseded by the Zapatista movement which was about interconnection and horizontality, not a small elite galvanizing the masses.

I think the Funnel played an odd middle role. The Funnel membership was committed to changing filmic content, to get over the suspension of disbelief in order to create active viewers. But it was also about bringing people in and providing access to technology so that they could express themselves. They’re not just activated viewers, they’re activated makers, which is not part of the old vanguard model. The old vanguard model is modernist, while the distributive model is postmodern or anti-modern. Hence the unquestioned willingness to include or invite queer culture into what was not a particularly queer space. I think members saw that there was a ripple effect when newcomers were granted access, the forms of representation change, and the more this happens the more we can survive as a group against capitalist hegemony.

Mike: There’s a tension between the two models you’re describing. There was the outreach you note, but part of the Funnel was very exclusive and inward focused. And this clubhouse feeling was enshrined in a suite of bylaws and insider codes that meant that to become a “full” member (who could sit on the board, and help make decisions that would steer the organization) you had to be voted in by the existing board.

David: That’s where it got tricky because I think people believed in full access, but the inherent structure, the tiered membership system, the distribution of privilege, was in complete contradiction to the ethos, to the motivating drive underneath. I think there was an attempt to address that, to rewrite the bylaws to be more inclusive, to make the structure match the political agenda.

Mike: Was that movement underway while you were director?

David: Hell yes. It started and collapsed while I was there.

Mike: For many the culmination of these dividing lines was the annual general meeting in October 1986. Dot Tuer introduced a motion that would grant associate members a vote on which “full” members could sit on the board. Given that most members were loathe to rejoin the Board’s endless meetings, and that people often had to be begged or cajoled to join, this voting right seemed at most, a rather modest proposition.

David: I was at the meeting where it was turned down. I was allowed to become a full member after my resignation in March 1986. Midi had resigned a month earlier, and I felt it was time to move on to allow the organization to regenerate itself. The membership application was a Byzantine process, I can’t remember if I had to have a spanking or what was involved. Half a year after I resigned the issue of privilege and opening up the membership came to a head with the October vote.

Mike: Both Judith Doyle and Dot Tuer said that for them the Funnel ended at that meeting.

David: Absolutely, I don’t think I ever set foot in that place again. The contradictions became untenable. We had to continue to reach out if we believed our own reason for being. I don’t understand why people had the proprietary sense that if they were the ones who had hammered that nail into that two by four it belonged to them. I respected the people who had built the theatre and done the renovations, I couldn’t have done any of that. But that is the downside of structuralism, if all that matters is the materiality, if there’s no political project attached, then a two by four with a nail in it is just that. A majority of members at the October meeting opted to stick with bricks and mortar.

Mike: Do you think the Funnel lacked a political project?

David: I think there was a very clear political project. But it became untenable. Everybody in the membership wanted to bring people in and help them make work and change the roots of representation. But the walls went up. I think the project had become attenuated, people were digging their heels in on both sides. One side wanted to open the door slightly, and the other side said no way. The membership was pretty evenly split, the vote was very close as I remember.

Mike: In 1989 the Funnel moved from King Street to a new space on Soho Street. Did you ever go to the Soho Street location?

David: No.

Mike: The Funnel closed after a season on Soho Street. Were you surprised to hear that the project died?

David: I was sad to hear that it was having difficulties, but there was nothing I could do. The people who made those decisions at the meeting got what they wanted, which was finally a small and miserable vision. Nobody knew why they decided to move to Soho.

When I was the director I realized that being on the east side of the city was both a detriment and benefit. I had regular meetings with John Goodwin at Art Metropole and Steve Pazell from Mercer Union (gallery) about joining forces to develop a joint facility for all three of us. I think there was always an effort, an underlying “Oh, wouldn’t it be nice if we were part of the action?” but we never did anything about it while I was there. People were more interested in taking full advantage of where we were and what we had. We had a great theatre, even if it was a little cold occasionally. The gallery was terrific. But moving was never on the agenda when I was there. Our priority was to develop the technology base and to support the programming and its documentation. We actively sought out curators and produced catalogues.

Mike: Were you surprised that the Funnel moved?

David: I was very surprised, though I wasn’t involved in any of those decisions. I was a full member but saw there was no opening for me. As someone who was making things again, it wasn’t a community I wanted to be part of anymore. I don’t know much about what happened subsequently, but I was very surprised that they moved and rebuilt the theatre. I thought maybe that’s what they’re really good at. I never went to a screening there, I have no idea if it ever opened.

Mike: Could you speak about the importance of catalogues, why did they matter so much at that moment?

David: Curation and publications were conceived of together. Publications at that time were the primary means of communicating what was going on at the Funnel. There was a distribution collection that Jim Anderson did a lot of work with, he shipped films to the circuit of experimental films around the world. The catalogues put the Funnel into a broader context, both in terms of the work shown in the programs, and people finding out what the Funnel was. Our print runs were large enough to ensure that the catalogues went to libraries, universities and bookstores. We had a distributor in Peterborough. We did two rounds of curated programs and publications that were quite successful.

Curation is basically about editing, you put things together so that they reinforce each other to make a meaning greater than the original elements. We brought in independent curators to look into the realm of experimental cinema in general and to give the work at the Funnel recognition and a broader context. This was a period when there was no internet and no computers.

The catalogues were an example of enhancing or distributing accessibility, as opposed to the final moments of my experience with the Funnel which was about shutting it down. The long-term impacts of that limitation means that many documents are not accessible, but the catalogues are still available and part of a public history.

Mike: Was the Funnel a place of intellectual discourse?

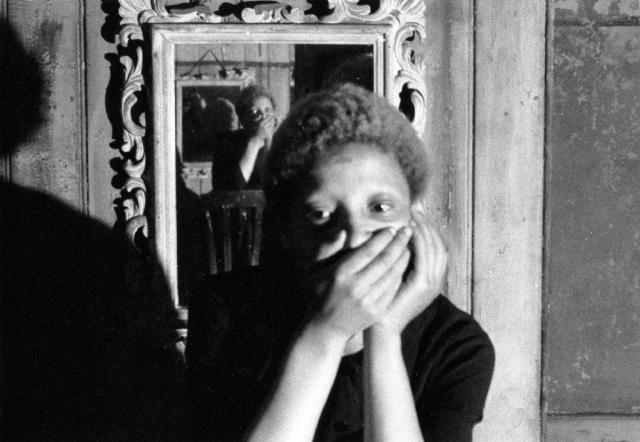

David: I think there was constant debate about everything. The Funnel took up its own challenges very seriously and substantially. I remember having intense discussions with Anna Gronau about the film she made when I was there, Regards, which raised questions about the cinematic apparatus, and the positioning of gender and the look, and the play of language. There was a lot of discussion that came out of the writing of French feminists in the period like Luce Irigaray.

The Funnel was a place where zine culture thrived. Zine culture didn’t flourish at many other artist-run centres, but it sure did at the Funnel. I’ve already mentioned two: Dr. Smith and the J.D.’s. And while we may not want to think of zine culture as the vanguard of academic discourse, it has survived a lot longer than some of the academics we were talking about at that time. They became central to a cultural shift. I think the Funnel positioned itself as a place of thinking and making, there was an attempt to broaden the context and introduce other frameworks for what we were doing.

A year ago I was in Buenos Aires and a friend said he was going to meet a filmmaker from Britain. It turned out to be Sally Potter. Thirty years after the fact, she remembered showing her feature The Gold Diggers (1983) at the Funnel. She’s still largely an experimental filmmaker, though she has more money and connections to actors.

Mike: In the eighties, Sally Potter appeared as part of a new movement of feminist, neo-narrative, critical cinema.

David: She came out of the London Filmmaker’s Co-op, which was one of the core places for integrating feminist thinking in that period. Sally was also part of a movement away from strictly structural-material film which only wanted to make pictures of the apparatus, or forbid images of people altogether. In that period people were really trying to wrap their minds around a shift, there was a new movement in experimental cinema dealing with representation and figuration. Narrative didn’t have to be given over to Hollywood, we could also take this up somehow. Judith Doyle, Anna Gronau, Michaelle McLean, Midi Onodera and Ross McLaren were all trying to do that in their own ways.

Mike: I’ve interviewed many Funnel members who attended hundreds of screenings, but when I ask about significant evenings most draw a blank. It makes me wonder about the impact and legacy of fringe cultures in general, if no one can recall a note, did the music play?

David: The structure of memory is such that the endless Funnel meetings have turned into a blur, but if you showed me an agenda, I could recall every detail. If you showed me a screening calendar, I could give you a list of what happened in each film. I have a photographic memory.

I think that my commitment to ongoing forms of representational resistance is strongly grounded in my involvement with the Funnel. I’ve never given up on that, and I’ve been very fortunate position in the last ten years to be able to make artworks in a new way, new media works that I feel are taking that ethos in a new direction and at a different scale. I think the Funnel has had a tremendous impact on my life, it’s had a fundamental impact on how I see the world, how I see making things and the purpose of making things.