Story of the Eye by Blaine Allan (Afterimage October 1984)

Focus on Anna Gronau by Elke Town (Canadian Art Summer 1990)

Mary Mary by Anna Gronau by Blaine Allan (New Work Showcase 1989)

Mary Mary by Kim Derko (Fuse Magazine, 1989)

Story of the Eye by Blaine Allan

Regards by Anna Gronau, distributed by The Funnel Experimental Film Theatre 507 King Street East, Toronto, Ontario M5A 1M3 Canada

Originally published in Afterimage, October 1984

Anna Gronau’s thirty-one minute film, Regards, concerns processes of communication as translation. In a series of separate but related sequences, it outlines the determining limits of identification and recognition in visual and verbal language.

The film begins with a series of coloured, high-contrast images: an egg, an arm crossing through the frame, a woman’s figure. One image recalls the traditional figure-ground test in which the viewer can see two faces in profile or a vase. The view opens up and resolves into a looped shot of a naked woman, seated at a table, eating a boiled egg. A blue arrow follows her movements and then points at other objects in the frame. In a later sequence, an older woman covers one eye with an occluder, looks just off camera, and reads a passage from Bataille’s Story of the Eye. When she finishes, we see the enlarged text, upside down, and her hand enters from the top of the frame and tracks the spaces between the words. In a concluding sequence, another young woman, seen from above, makes a drawing. The camera tilts from the completed drawing to reveal a blonde girl who sits beside the paper playing solitaire. The camera finally comes to rest on the drawing’s object, a model of a theatre stage.

Battles between human values and mechanics occur in a number of films by Canadian artists. In David Rimmer’s films of the 1970s, for example, wry humour surfaces in rigorous, often mathematically precise exercises in optical printing, and Bruce Elder’s recent work structures complex layers of personal images and text. In the context of her own film work and of others’, Gronau’s Regards demonstrates a similar, dual quality of exploring the uses of images and the means by which we understand them.

An earlier, shorter film, In-Camera Sessions, examines the problems of power and control over cinematic mechanisms. Wound Close and Aradia, which predate Regards in release, but follow it in conception, both speak in distinctly female voices and employ explicitly mythical and ritual images new to Gronau’s film work. Regards anticipates the later films’ concerns with female discourse and extends the earlier film’s impulse to precisely locate cinematic meaning. Gronau used a malfunctioning camera to shoot In-Camera Sessions, and the resulting effects (or “defects”) centre the film’s concerns on the relations of the filmmaker to the filmmaking activity. Regards, in contrast, demonstrates rigour and control over the image, and its elegant puzzles open spaces for participation at the other end of the circuit in which people make and see films. Thus, the film deals with relations between film and spectator. While we may realize that film viewing is a form of work, Regards really emphasizes that fact.

Regards’s breakfast sequence continues elements seen in Michael Snow’s Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) and Joyce Wieland’s Catfood. Both Snow’s and Gronau’s films affirm the planar quality of the film image, using breakfast scenes. Snow makes the film plane concrete and a part of the action, as he sets it in motion and it flattens the domestic still life against a wall. Gronau flattens the image through rephotography and by including, at the bottom of the frame, a printed title. Wieland’s cat eats fish after fish, and Gronau’s loop-printed woman continually spoons up food from an apparently bottomless egg. In Wieland’s cat, we can observe animal behaviour in new ways. We may attribute human qualities to the animal, or we may view it as a metaphorical social consumer. Gronau’s woman remains more evidently a spectacle. Her nakedness renders her a traditional object of observation or an artist’s model. Her placement in the frame and in the setting – in profile against a wall – minimizes depth and reinforces the image’s planarity. The animated arrow that skates across the two-dimensional image stresses its flatness and makes clear the image’s function as illustration.

The processes of physical movement, reading, and drawing in the film all involve perception and the activity of interpretation. The three women, who play the film’s four roles, all use their eyes and hands. However, the structure of the film separates them from each other; no two characters ever appear in the same shot. In addition, age marks a difference among the women, but also suggests connection among the characters as distinct aspects of a common experience. Even the simple and fundamental activities of eating, reading, drawing, and playing entail systems of communication, exchange, and conversion. The film represents these complex systems in the basic and apparently natural coordination of hand and eye, a system of translation and information exchange common to virtually all animals.

Activities that require sophisticated hand-eye coordination specifically suggest traditional fields of work for women. The film imposes strict limitations on the four women, implying suppression of women’s experience. Even within these boundaries, however, the film traces a progress toward mastery. The woman who eats is caught in an optical loop that repeats her movements over and over. The elderly woman reads from an enlarged text, like a vision test from an eye chart. The first lines of the drawing, parallel to the film frame, indicate the limitations that the film itself supplies. Upside down, however, the drawing is oriented for the artist and not for the spectator. This inversion links the artist drawing with the viewer watching the lines mold themselves into a recognizable image. Regards, then, reproduces the process of drawing – not just its final result – and imparts the artist’s experience of discovery to the viewer. The solitaire game – the only activity that the camera refuses to linger over – is the most sophisticated of the film’s systems. We see the youngest of the women mastering the conventions and regulations of the game, an act that suggests the learning process that looks beyond the film’s conclusion.

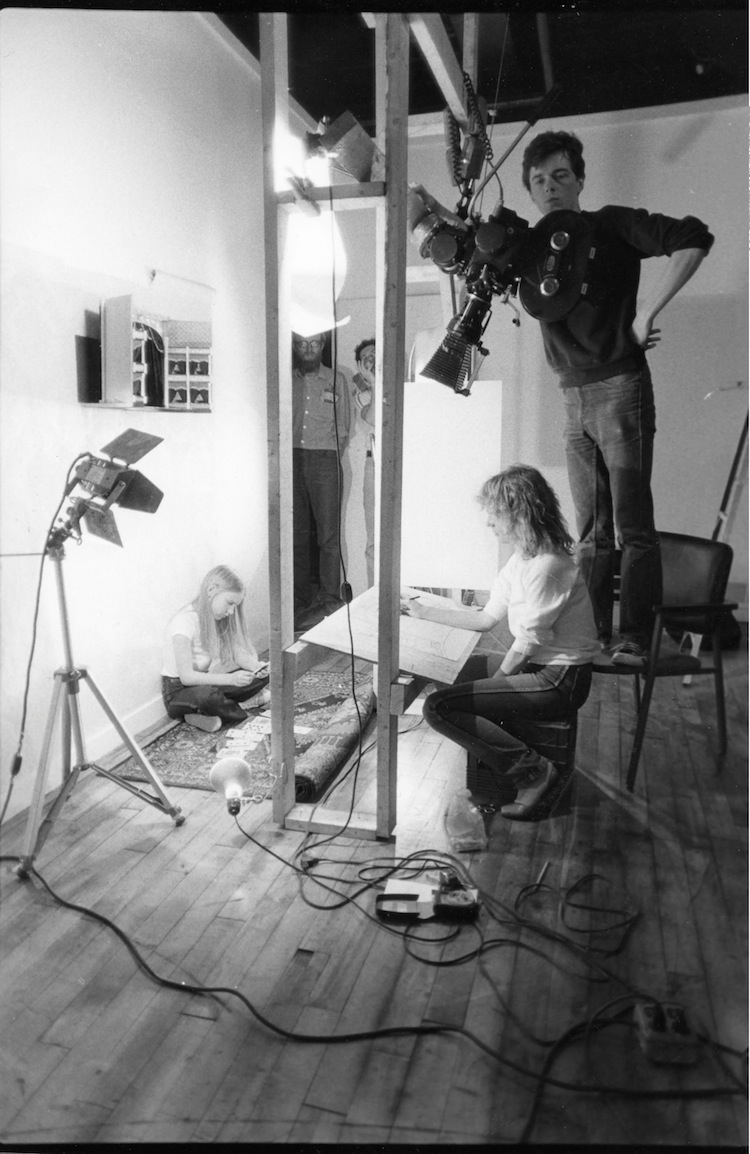

Shooting “Regards” by Anna Gronau at the Funnel L-R Amber Sansom, Villem Teder, Paul McGowan, Anna Gronau, Ross McLaren. Photo by John Porter

Both image and sound tracks address us directly, thus involving us in a process of translation and learning. A caption below the looped shot reads, “What is it.” The words suggest a question of identification, and the blue arrow seems to propose an answer. But the words form only the first part of a longer sentence, which voices on the soundtrack translate into French. Most of the voices render the passage segment by segment, as it appears onscreen, and not as a coherent sentence. The translation short-circuits several constituent elements of language, such as syntax and diction. However, this rerouting does not destroy meaning; it transforms the sentence’s value into the produce of construction. The attempts at translation do not produce a correct, single answer, but numerous options, all with degrees of accuracy. Correspondingly, the correct answer to the question that the film poses in writing – “What is it that makes breakfast so different from other meals?” – is not a single answer, but a network of delimited possibilities.

Regards concludes with a superimposition that recalls the double images near the end of Michael Snow’s Wavelength. Both Snow’s and Gronau’s films simultaneously depict process and result by showing the destination and the way to get there in the same image. Snow’s leap into the photographed water marks the end of his film’s erratic, continual zoom. Gronau’s camera moves from the drawing to the drawing’s model. She holds on the model image and superimposes the finished drawing and the tilt across the floor until the two layers converge into one. The film closes on the inverted image of a theatre stage, underscoring its concern with information exchange as performance and performance as the execution of a preexisting text or model in a differing system. The coda of a double image imposes closure on the film. The double image returns us to another, ambiguous double-image – the two profiles – which earlier in the film raises the questions of figure and ground and of the perceiver’s place in determining the limits of meaning in an image.

Focus on Anna Gronau by Elke Town

Originally published in Canadian Art, Summer 1990

Anna Gronau is a Toronto-based filmmaker whose 1989 55-minute film Mary Mary is her first major work since 1983. In addition to making films, Gronau has been active as a film programmer, writer, and lecturer. She was also a co-founder of the Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society, which was formed to legally challenge the censorship of film and video in Ontario.

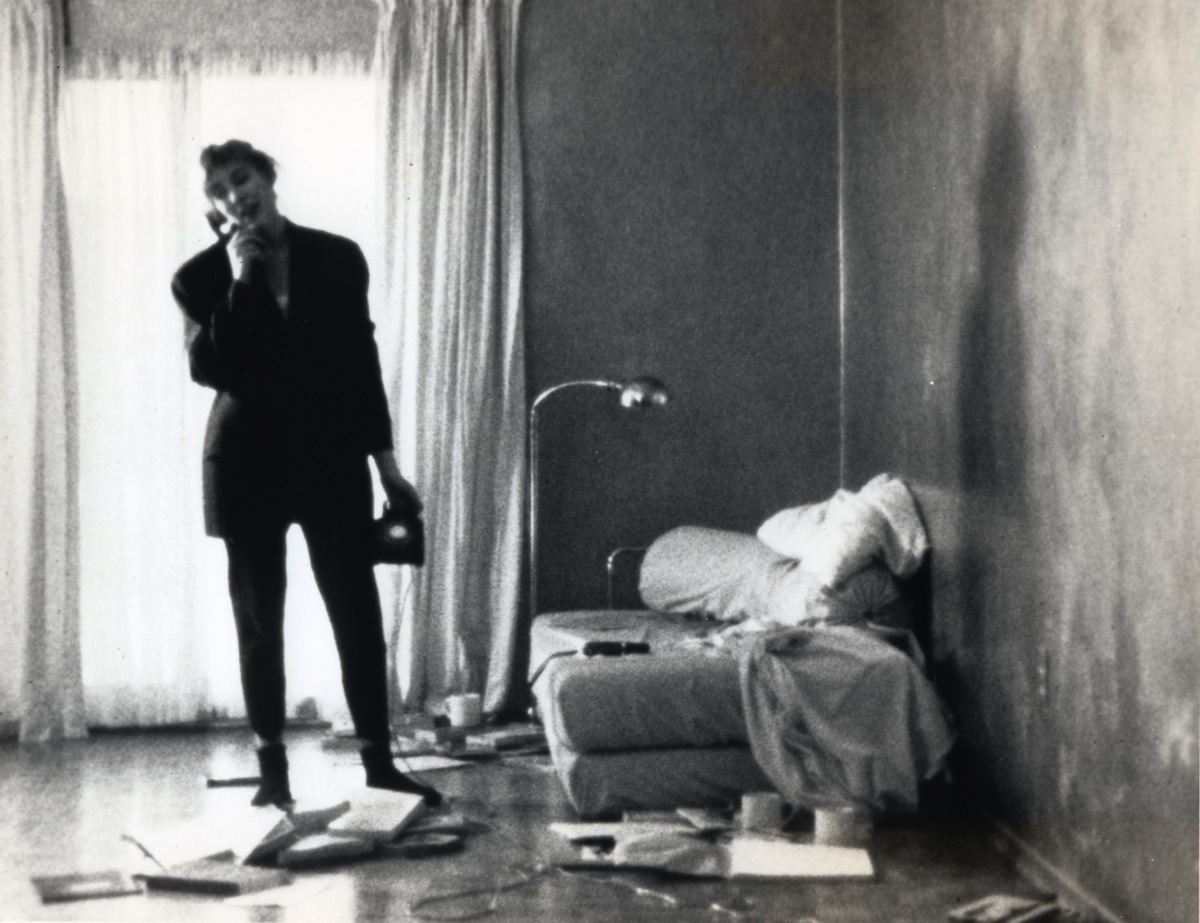

As though to echo Gronau’s six-year filmmaking interlude, Mary Mary is about a filmmaker, M (played by Patricia Medwid), who is planning to make a film. To her dismay, the film’s script eludes her. M has isolated herself at home and taken to her bed. Caught in the tangle of her bedsheets, alone with her books and tape recorder, she is consumed and confused by quotations and references from fiction and film. M’s inability to give order to a growing array of material immobilizes her and reduces her at one point to speaking only in elliptical quotations. She is haunted by histories of places and people, and at the mercy of memories, dreams and desires from which she can construct no coherent order.

By the time she is ready to begin her film, M laments to a friend that “The film wants things I don’t want – stories, history, acting.” Caught in the web or her own narrative and history, she cautions, “Never dabble in autobiography unless you want a perfect world that perfectly excludes you.” Yet the need to answer questions about how to deal with the self within existing systems of representation finally propels M into action.

She puts herself back in the picture precisely by entering the world of stories and history she has wanted so much to avoid. She leaves her self-analysis behind and heads down the same road that opened the film – the road to the house overlooking the bay, the home of her deceased grandmother. With the spell now broken, and on the site where she will make her film, M is reconnected and able to construct a cumulative history of herself that does indeed include her. Her own observation that “the dead are not powerless,” that they live as potent fictions and accrued history, becomes the central philosophical motif of the film.

Circular and complex in its composition and use of metaphors and association, Mary Mary is rich with layers of references, cross-references and revelations. Structured as a film within a film, a narrative within an analysis, it draws on sources as diverse as Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Victorian children’s novel A Secret Garden, and the issues surrounding native rights. Autobiographical, biographical, and fictional at the same time, the film relies for its effect on spoken, written and visual language, as well as a haunting music track composed by Stephen Donald. The viewer is drawn into Mary Mary by its intimate narrative and seductive visuals: M in her voluptuous satin bedsheet, underwater images of swimming polar bears, and a breathtaking pan off the garden at the bay house. These, combined with Graonu’s blatant and ironic exploitation of familiar filmic devices, make for a film that stirs the imagination and intellect alike.

Mary Mary by Anna Gronau by Blaine Allan

New Work Showcase, Kingston 1989

Originally published as program notes from New Work Showcase, a program curated by Blaine, and supported by CFMDC

The title sequence of Mary Mary employs what is now a conventional modernist strategy that signals the status of the film as film. Under the superimposed credits, the production crew sets up for a shot while the director and principal actor run through the scene. A second camera depicts the moment in black-and-white, catching it in imbalanced compositions that connote informality and spontaneity. Doubling and redoubling the image-making process, we see the camera ready to shoot the scene, as well as the video camera and monitor used for rehearsal. The incorporation of such self-reflexive devices has often had a critical role, providing a grounding in the realities of producing the film. In Mary Mary it introduces a structure that interlocks layers of reference, memory, and dream throughout the film.

The central character is “M.,” a filmmaker who has isolated herself in her flat – really in the corner of the room where she sleeps. She is awakened by telephone messages, but her excursions out of the house are dreams, memories, memories of stories, and such means of leaving a place without walking out the door. Finally, she does venture outside, driving from the city to the country, to her grandmother’s house, which sits amid summer foliage, by the water.

“M.” stands for her name, Mary, as she is later identified, but the name also refers back to Mary Lennox, the protagonist of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1911 novel The Secret Garden, one of the stories locked in the character’s memory. “A.,” who in a dream meets “M.” by the viewing window for the Metro Toronto Zoo’s polar bear pool, is Mary’s mirror image. On the one hand she is the Anna who is making the film and who plays her, even though her voice belongs to “M.” Yet “A.” also suggest the peripatetic hero of another story key to the film, Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There.

During the title sequence, filmmaker Anna Gronau’s voice identifies a piece of sound with the film’s working title, House of Cards, and the film is punctuated with four sets of superimposed titles, each set containing thirteen messages, and each title numbered, like the cards in the four suits of a deck of playing cards. The image of a deck of cards offers a metaphor for the film’s structure and the possibilities for negotiating it. Always caught between order and randomness, with the capacity to be repeatedly re-ordered, they might be tools for gaming, like playing cards, or the instruments of magic prognostication of the Tarot.

The numbered titles do not provide easy or conclusive answers to the film’s puzzles, but they do outline several distinct themes. Each set starts with a passage from Through the Looking-Glass, Alice “floating” down a staircase, suggesting the ethereal tracking movement of Gronau’s camera through and around the house by the bay that serves as one of the film’s geographical centres. The Alice passages are followed by references to The Secret Garden, the story of an orphan sent to live with her uncle at his Yorkshire manor, and who revives a prohibited, derelict garden on the grounds, but also discovers a disabled cousin, kept hidden, and helps him to health. Other passages refer to the Greek myths of Artemis, the goddess of the hunt and the moon, and the sorceress goddess Hecate; native treaties and claims to land and self-government; and family history and property. The threads that run through the diverse verbal messages concern loss and the reclaiming and restoration of traditional signs of feminine identity: of responsibility (Artemis’s loss of the stars to Zeus, for example), of houses and homes, of names.

Mary Mary employs ravishing imagery and visual technique to draw the viewer into the subjective experience of the environment by the film’s central character, and locates a transformation of that character in the movement from city to country. “M.” lives in two houses, the city apartment of her present and the home of her family past, and they are depicted with a contrast that is conceptually simple, but emotionally effective. The restricted view of the flat and the stillness of the interior camerawork suggests “M.”’s self-confinement, but the silver-grey sheen on the wall stresses the coldness that surrounds her, in strong contrast to the sylph-like movement through the expansive, verdant countryside.

Perhaps the most striking image is the dream vision of a massive polar bear, swimming underwater. An icon at the centre of a network of meaning in the film, from the myth of Artemis, who turns one of her companions into a bear, to the mythical unions of human woman and bear. Viewed in the blue glow of the underwater light, the beast is at the centre of a dream by “M.,” a hypnotically captivating object or, as one of the film’s titles suggests, a cynosure, itself another name for one of the bear-constellations in the night sky. Occasionally tapping the viewing window with its enormous paw, it is one of the amazing things that Mary finds through the looking-glass.

Mary Mary by Kim Derko

Originally published in: Fuse Magazine, August 1989

“You have to decide if this is a film or a dream.”

Anna Gronau’s film Mary Mary opens with a lengthy, haunting, steadicam shot. The camera glides through a meadow, along a dirt road to the doorway of an old white house. Implied in this shot is the enigma of a suspended and floating point of view. What lies ahead is the investigation of a mystery and a search for the identity of this suspended point of view.

Gronau’s elaborate formal strategy offers a stabilizing effect (like the steadicam’s gyrostat) in a film that resembles a dream. The film is punctuated by a series of lists of text over image and readings. Passages from Victorian children’s novels and descriptions of mythological characters are interwoven with writings by and about North American native peoples, and with a recurring linguistic play on the words: STAT/STATE/ESTATE/PHOTOSTAT. The result is an inquest into the power of the “dominant cultural order” as it records and censors its own history.

The leading character of Mary Mary is M. – a filmmaker played by Patricia Medwid. M. is making a film but she encounters some of problems inherent in a feminist approach to plot, history and acting. This, of course, is no new dilemma for women filmmakers, but Gronau has M. pit plot against text, history against memory, and dream against image.

In a clever scene that takes place at the underground viewing window of an aquarium, M. meets A., who is a curious character played by “Anna Catherine Welbanks” – an actress who bears an uncanny resemblance to Gronau and suspiciously shares the filmmaker’s great grandmother’s maiden name. M. is confronted by A. about the nature of 8mm footage that appears later in the film. M. remarks that the 8mm footage is exactly as she remembers, although she had never seen it before. A. finds the footage disappointing and tells M. that “it must have been a screen memory.” M. retorts, quoting Alice from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass: “if I’m only a sort of thing in this dream, what are you, I should like to know.” The camera pans across the windows of the aquarium from M. to a swimming polar bear which has taken A.’s place. We later learn that Artemis/Hecate was a goddess who took the form of a bear and once ruled the stars until Zeus stole them away.

A. establishes, without “dabbling in autobiography,” that she wants to reclaim the stars. M. begins to construct a conniption between all of this fragmented information and her (or is it Gronau’s) own matriarchal lineage: great grandmother, grandmother, mother. It is from here that M. can develop a logic with which to structure her film and eventually find that position from which to begin shooting.

The memories of these women ancestors, on being identified, begin to assert their status and finally expose the “story behind the story.” The dead of M.’s past do not reclaim the stars, they reclaim their own history and Gronau reveals the soul owners of the suspended point of view.

Gronau’s film presents an overwhelming amount of information and I found the second viewing to be more satisfying than the first. Mary Mary maintains an elegant lyricism throughout its complex narrative structure: a film disguised as a dream.