Gift to last: a cinematic time capsule by John Bentley Mays (Globe, Feb 1982)

Content as Form/Film as Comment by Jennifer Oille Sinclair (Vanguard May 1982)

Eye of the Mask by Jennifer Oille (C Magazine, Fall 1985)

Judith Doyle, The Funnel, June 6 by Andre Jodoin (Vanguard Oct. 1985)

Speech and Representation by Philip Monk (1981)

Overlapping key to house of glass by Adele Freedman (Globe, June 1979)

Gift to last: a cinematic time capsule by John Bentley Mays

Originally published in Globe and Mail, February 1982

Two new films by Judith Doyle premiered at the Funnel Film Theatre (507 King St. E.) Friday night are scrapbooks of old amateur photographs that simply depict people and places in and around Collingwood, Ont. – pages turning on the screen while quiet voices tell tales about what it was like to live in the area and work in the shipyards of Georgian Bay many years ago.

Memoirs of relatives and friends long dead, reports of small-town jubilees on the dockside when big ships were launched, affectionate stories of other times – if these things aren’t what the works are finally about, they are the ribs and girders of this pair of small, strong films. And thereon hangs a tale worth telling about the unusual genesis and structure of Launch and Private Property/Public History, as the films are titled.

It all started last summer, when Miss Doyle was given a box of about 300 elderly black-and-white snapshots bought for $2 at an auction near Creemore, Ont. She noticed that many of them featured that big no-no of would-be professionals, the shadow of the photographer (a woman who wore a big hat) – and she decided to find her, if possible, and learn the story behind the pictures tumbled into the big box.

Following leads picked up from the auctioneer and farmers and workers in the Creemore area, the artist-turned-detective finally found the woman behind the camera: Edna Allen Lougheed, a long-time Creemore resident who now lives in a Thornbury, Ont., nursing home. From Mrs. Lougheed’s remembrances of times and people past, the long monologue overlaying the images that file past in the first film (Private Property/Public History; 18 minutes) was constructed. “I lived in Creemore. My father lived there for a long time,” begins the spare, intoned voice-over, as the grey and brown snaps turn by. “On the farm, we had apples and grain, and lots of pears. We took pictures for a long time…”

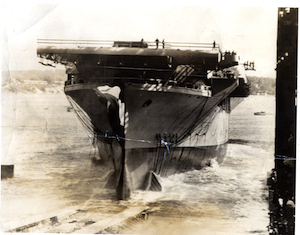

The idea for Launch (20 minutes) was sparked by Mrs. Lougheed’s reminiscences about ship launchings in Collingwood. The two monologues (one by a woman, the other by a man) are based on the ruminations of old-timers about the building and spectacular launches of the big ships. Like the first film, Launch is composed of a long sequence of high-contrast still pictures, this time garnered from the Collingwood Museum.

They may not sound like it, but such subject matters (personal history, workplace memoirs) are among the trickiest in the book, which is why most artists steer clear of them altogether. It’s hard for an urban, middle-class artist such as Miss Doyle – a late-seventies graduate of Queen Street’s switchblade-chic art scene – to deal with country folks and hardhat workers without turning them into monsters (a la Deliverance) or paradigms of down-home wisdom.

But she adroitly avoids both traps by keeping her work focused on her real subject, which isn’t people, but the structures of consciousness and identity (tales, family photos, fictions, memories) we use to frame our lives and give them meaning.

Nobody needs to be reminded that, today, such structures are in crisis. The communities and families Mrs. Lougheed remembers are disappearing, or changing beyond recognition; the ship welder who gives the marvelous monologue in Launch contrasts the craftsmanship that was, in his day, carefully and imperiously transmitted from father to son with the fumbling of his apprentice, who learned his welding at the local high school.

These narratives are saved from becoming mere items of nostalgia by the tautly written script and the crisply edited procession of images. Each film turns into a cool, elegiac report on worlds passing away and beyond that, into a metaphor for the slow, continual decay of all that is tried-and-true – a decay, as we find here, that’s hard to understand, and hard even to acknowledge.

*

The Funnel screening of Judith Doyle’s new films is the latest event in the series, sponsored by A Space and curated by Philip Monk, entitled Language and Representation. The series continues with Hell’s Open Kitchen, a drawing installation on view until Feb. 6 at A Space (299 Queen St. W.). It will conclude with an installation by Missing Associates (Lily Eng, Cori Palmer and Peter Dudar) at A Space, Feb. 9 to 24. Missing Associates will also present a film and performance at the Funnel at 9p.m. on Feb. 12.

Content as Form/Film as Comment by Jennifer Oille Sinclair

Originally published in Vanguard, May 1982

Be sure to check out Jennifer’s fab website: http://printingrocks.com

Under the auspices of A Space, Philip Monk curated a series of film, performance, installation, architecture and graphics denominated as Language and Representation. It concerned the way artists position themselves in relation to that which is represented, and how they bring that representation about by the relations of the codes of representation among themselves and to their content and reference.

As part, Judith Doyle screened two films, Private Property/Public History and Launch, in tandem. The first was about a family, its friends and the sense of a community in rural Ontario some time ago, a chronicle, its scenes constructed from snapshots taken by the people involved, its soundtrack scripting a dialogue out of conversations with six of those people. The second was about the shipbuilding industry in Collingwood, Ontario, a chronology, its scenes also constructed from snapshots taken by the people involved, its soundtrack scripting two monologues out of conversations with three of those people. The material was the stuff of which history is being made, an alternative historiography based on the traces left by everyman – in the manner of Montaillou, a book reconstituting life (from body language to myth) in a fourteenth century southern French town out of testimony in the local Inquisition Register. A beyond more than the headline.

And more than document, Doyle’s films are historical critiques about the changes of state in the two kinship systems that have structured society – the family and labour.

The family has perpetuated itself within itself (and without) by the circulation of images of itself. Ancestors and descendents lending credence to each other. When a family ends, the pictures go out of circulation as private property and into the interpretation of public history. A family as archetype for The Family. Appropriately, Doyle received the snapshots used in Private Property/Public History as a set of 300 sold at auction, another signifier of a family – its demise. Some feature the photographer’s shadows, a female form. Doyle found the figure, Edna Allen Lougheed, very fragile, very old, in a room in a nursing home, one in a row of those crib-like beds meant to keep the occupants in, or from falling out. Their talks opened an area, the compilation of a picture that is trying to piece the past together but leaves it as an open book. Behind the scenes of Private Property/Public History, two women are talking over photographs, on the screen are seen the pictures, only the speakers’ words (can) frame the events, episodes and epicentres that figurated a family’s life.

“I lived in Creemore. My father lived there for a long time… on the farm we had apples and grains… We took pictures for a long time/hard times… had to liquidate some property… they mightn’t have been what we would today consider problems, just a shortage of cash flow… caught in expanding/See there’s quite a family that went out west… scattered… so the photographs – I suppose they sent them back and forth out west to keep in touch with the family/There was one piece. Villa… Yes, that’s Villa Allen there. She died suddenly… I think she choked.”

But the death of a member is not the same as the death of a or the family.

Sometimes memory falters. A big fire is imprinted in the mind’s eye. But details fail – “It burned down… That place is burned now, it’s gone.. they must have taken 20 pictures of that…” – and the narrative leaves questions unanswered and becomes a stream of consciousness – culture’s.

The words articulated by the pictures in Launch (from the collection of the Collingwood Museum) bespeak another kind of circulation. Collingwood people have always photographed the town’s ship building, especially the launch, then talked over their respective images – the work, its conditions, its import, the industry, the union, the company, what is right, what went wrong, why.

“… the men hammering the blocks out from under the boat… when she goes in you’ll know. There will be a huge tidal wave/(shipbuilding) is the major industry of Collingwood, a year round source of employment/It’s just the hull… a number… that is launched… the christening is after it’s named… ready for the sea… that’s a ceremony… But the launch is the real event. It’s spectacular… the mechanics and workmen go on it… do everything to try and break it in/(shipbuilding hasn’t been) like putting out a car… those guys are quite proud of their workmanship… a personal achievement…”

“Now we have what is called prefabrication. They build all the sections in the shed, then they take them out and join one unit to the other/I belong to the steelworker’s union – so does everyone at the shipyard. It’s garbage… suppose we pay $20 a month in union dues. 90% of that gets down to the States and never comes back here…”

No matter how common, the content of both films is extremely subjective, the verbal and visual evidence of the individual, the experiencer. Doyle has objectified this integrity, without distortion or exploitation, into a structure, a structuralism, that is independent but dependent on her mind, the material and the medium for its communication.

The films are one in their theoretical dialectic – a family dies out, its goods and chattel up for bid/the family is dying as an institution, disvalued; the concept of labour is losing out to the ‘rationalization’ of industry – a two year collegiate course replacing apprenticeship from the age of fourteen, machines displacing man, the tool replacing the hand. In contingence, the films are bound by formal dispositions, the crossing of references. A picture in Private Property/Public History shows a woman working in a shipyard. “It would be the First World War gauging by the smock she’s wearing. Here’s a picture of a ship launch.” A picture appears in Private Property/Public History of two women and “…here’s your shadow…” In Launch, the picture reappears and the speaker says, “You should see inside the boat, but the person that shows you around knows nothing… That photograph. Now I can tell you how tall that woman there is, and how far the cameraman was from her. And I’d do the same if I was building a bridge across here. You can take the shadows, you measure shadows from one direction, from another direction, and from the straight direction… you should be able to measure it out…” Both films refer to colour, a surface that has become the substance of family and labour. Private Property asks “How do you judge a photograph?… Composition, colour and sharpness… Impact is… colour… whether the colour is outstanding.” Launch says that “the beams… were never painted until they were on the job… Now everything is paint… Thousands and thousands of gallons of paint…”

Equally suited to the dialectic, the two films are structured out of distinctions making a whole out of opposites. In both, the images cue the speech but Private Property/Public History assumes a dialogue, a conversation between two women; Launch assumes two monologues, a woman’s and a man’s, addresses to the audience –private versus public history. For both films, Doyle re-photographed the original snapshots on 3” X 5” cards to ‘vericolour’ a picture more compositional, less featural, and then shot these pictures with Super 8 on an animation board. Private Property holds the scenes for random lengths while the voices ramble into other dimensions – young ladies in their finery are gathered on a lawn/”People vote now for the man they think is going to do the most good for them, regardless of party. At one time, if you were born into a Tory or Grit family, you bloody well stayed way, or you were disowned by the family.” However, Launch holds each scene for 29 seconds and doesn’t take tangents. The first method is the mood of intimate retrospective (why? when? where?); the second is that of immediate relation (the what of that’s it and that’s that). The views represent ways of seeing, looking at history, vantaging frames both fading – the myths of the family, concrete labour. Launch held three scenes longer than 29 seconds, certain ships and a certain shipyard speaking of an elsewhere important to the speaker – “… the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth… my father and my brother – they marked every beam on those boats/John Brown’s (a shipyard in Scotland) had ten thousand men. We could build, at one time, 6 destroyers, 2 cargo boats, an aircraft carrier, a battleship, a cruiser…” Times past. If it weren’t for his kin, this plater would have been an accountant. The past speaks of a time when labour created family, proud of its product, a class relation.

Midstream through Private Property… there is a picture of a man by a fence that could stand as a parting shot for both films’ stances. The man could be Dalt, Edna Allen Lougheed’s husband – “He always had the look. He was looking past you. You know some people when they look at you they’re sort of looking over you or through you or over top of you?… (others are) looking behind you… that’s what that guy’s looking like to me anyways…” Or this could be a picture of the artist in society.

While specific to circumstances, Doyle’s films sweep in innuendo. Seen as ‘art’ in the city of Toronto, they acted as interventions in an art scene where the family, labour and the rural are rarely conjured, or seldom more than ideological affectations. When screened in Collingwood, they will not be seen as ‘art’ impositions but as actual immanences – distillations of years worth of disparate moments within the viewers’ realm into two cogent twenty minute spans. That is the film’s rare commodity – their levels of reading being seen in the right place at the right time.

Eye of the Mask by Jennifer Oille

Originally published in C Magazine, Fall 1985, No. 7

Judith Doyle “Eye of the Mask” The Funnel, Toronto June 6

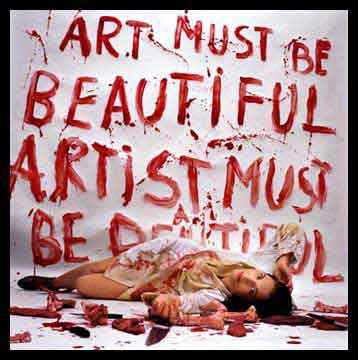

Art, of course, borrows historical styles and subjects and the conventions of other disciplines. And artists borrow other people’s experience, suffering, revolutions, identities. In this regard, one thinks of the American middle-class students who, in the 1960s, appropriated radical causes and acted for the oppressed (a surrogate expression of personal disaffection? An activity which gave them, psychologically at least, the stamp of moral legitimacy?). And one thinks of the short-lived Russian organization Proletcult which maintained, in the 1920s, that only the working class, the ‘we’ that built the ocean liner and the airplane, could build a proletarian culture, an interdiction which precluded the intervention of the middle-class artist/intellectual reared on individualist principles. Then one could think of, for example, the enterprise of Carol Conde and Karl Beveridge. In It’s Still A Privileged Art (1975), they related their dilemma as ‘fine artists’ engaged in private practice who believe that art must become responsible for its politics. Subsequently, the labour movement provided them with a contextual situation. Its collective experience could be the base for a socialized culture while “fine art” could only sustain individual practice (which refused to recognize the social base of production in an industrial society). In their docu-fictional accounts of recent episodes in union history, they assume the voice of the subject rather than their relation to it. Yet who are they addressing? Can the ‘leftist’ artist be of service to the socio-economic left? Surely the labour movement doesn’t need Conde and Beveridge to decipher and articulate its experience.

Judith Doyle’s work both deliberately appropriates experience other than her own and addresses the question of appropriation. It is both an examination of the change in view when a body of representation is taken from its original context of interpretation and an analysis of her position as an artist in society. It has, so far, served as an intervention in the art community.

Her film Private Property/Public History (1982) was about a family, its friends, the sense of community in rural Ontario some time ago; Launch was about the shipbuilding industry in Collingwood, Ontario. The scenes in both films were constructed from snapshots taken by the people involved in the first case from a set of 300 family photos sold at auction) and their soundtracks were scripted out of conversations with people in the areas. Her performance Rate of Descent (1983) articulated the correspondence between Roger Van der Weyden’s production and her own, thereby employing fifteenth century painting as a medium for a contemporary construct. Slides showed details from his religious paintings. A text explained the structure of the paintings – the flat backdrop, the formal rhythm of the figuration – and Doyle’s relation to this structure. In trying to justify the claim to be an artist “as a person in a room waiting to become an artist… I wanted a lucid, flat, transparent, light. That was what I thought I saw in the paintings.”

Simultaneously Doyle published her conversations with Brother Martin Shea, a missioner of the Maryknoll order in Latin America, in Impulse. There was an intricate, albeit unwritten correspondence between the performance and the publication. The imbalance of the scales (evil outweighs good) in Van der Weyden’s Last Judgement and the appropriation of suffering implicit in his Descent from the Cross find their equivalent today in the Maryknoll mission, an aspect of cultural intervention predicated on the non-necessity of the prevailing order. Working alongside the natives, appropriating their suffering, the missioners practice a ‘theology of liberation’ – the history that has been written in white hands should be rewritten in Third World terms. Van der Weyden’s formal vocabulary, the flow between line and gesture and movement reflects the Maryknoll intervention: “In the paintings people are all separate on this earth… but connected on a more abstract plane, by a line which is a line of compassionate movement.”

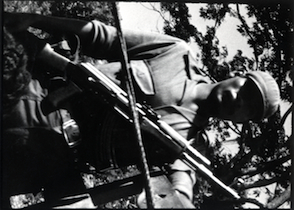

In the winter of 1983-84 Doyle spent several months in Nicaragua making a film about a country in revolution – perhaps it would be better to say a country where the one secure thing in life has been that nothing is secure. It is a documentary that does not pretend reality. In Eye of the Mask, Nicaragua is seen through the fictions of religious, ritual and theatrical representation. Eye of the Mask has three foci: churches, their decoration, graphic illustrations of cultural transplantation and re-interpretation; the religious festivals of Purisma (commemorating the conception of the virgin) and the Gigantona (the parade concluding Purisma featuring giant puppet costumes as European women); the Nixtayolero theatre group, its combination of native and European narrative modes to configure parables of social and spiritual incarnation.

The film is an appropriation – it is not Doyle’s country, culture or revolution. The film is about appropriation, in all its variations – Catholic custom has been imposed on native tradition, propaganda theatre has borrowed native culture for political expedience, the state is borrowing native custom and Catholic tradition as elements in a Nicaraguan renaissance… The film is about identities, assuming roles, the question of identity – no one plays themself, everyone is filmed as a performer, as a member of an audience, as an artist – just as the filmmaker has assumed the role of artist and questions its function.

The film is a structure of contradictions, a correspondence to the contradictions inherent in the country – between past and present, between native and European, those of any revolution.

We are in a church. The religious art shows traces of native influence, a presence which is re-interpreted in light of the revolution. “This artisanship is a culture of resistance, simply because it survives.”

We are in Leon, watching the championship of the Gigantonas, the fourth such event, promoted by the Leon Popular Culture Centre, the Neighbourhood Defense Committees, Sandinista Youth, City Council, the Regional Government Delegation.

We are looking at a Purisma altar, one of the thousands throughout the country made from whatever bric-a-brac, glitter, plastic dolls, plastic icons, twinkling lights each family collects or inherits.

We are in a nightclub in Managua – Lobo Jack’s “Plastic City” – watching a singer: “There are things in life, my love, with no explanation.”

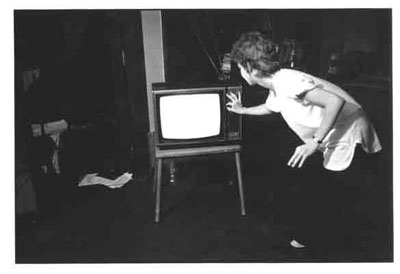

We are watching television. “Comrade television viewers, tonight the Political Directorate of the Sandinista Popular Army presents this edition of Only One Army. Our army is the most selfless, self-sacrificing and disciplined in all the terrestrial world, because it knows its historical role.”

There is a constant refrain – the role of the artist in revolution. We are with the Nixtayolero (Dawn Star) theatre group. It travels about the country, not to give solutions, but alternative choices through theatre. We listen to its leader, playwright and dancer Alan Bolt: “We are not trying to develop actors. We are trying to develop theatre workers. I see a theatre worker as a human being working with human beings to change reality to have a better society.”

But how? Working with the Indian communities, with the Miskito communities, with local peasants, he discovered that although the theatrical vision was correct, the mechanisms, the instruments, were not. Theatre had to start fundamentally from native traditions in order to be accessible. For example. Initially people thought it would be very hard to overthrow Somoza. There was a saying “hoping to kick out Somoza is like hoping that crabs can fly.” So Nixtayolero developed a play: Once upon a time there was a little crab who was digging a deep hole in the ground, when suddenly a torcaza pidgeon appeared… Why do you want to live deep in a dark hole if you can live up in the branches of a tree… I’m only a crab… In life you can be anything you want, so at least be a crab with willpower…

Bolt never questions the revolution. But he asks another question twice: “Is the theatre that we are doing a real popular theatre? Are we trying to impose ideas on people or are we trying to develop the awareness of the people? Are we using real symbols of the popular tradition, or are we just fooling ourselves?”

Hardly questions Russian artists/propagandists asked themselves in revolution.

But Eye of the Mask is not a study or propaganda – or a comparative analysis of the use of popular culture in Russia or in Chile under Allende.

Not is it the kind of film one might have expected from Doyle after the enraptured account of her visit to Nicaragua (Vanguard, September, 19830. Putting Nicaragua into the perspective of her own production has distanced her from the infatuations of the ex-colonizer for the de-colonialized and has produced a work which is an intervention into the public perspective. Eye of the Mask is a metaphor for a country in which everyone plays a role – to mask themselves from the enemy, to present a face to the cameras of the world of which they and their country are a constant focus.

Judith Doyle, The Funnel, June 6 by Andre Jodoin

Originally published in Vanguard, October 1985

Judith Doyle’s film Eye of the Mask, Theatre Nicaragua, documents her travels with the Nicraguan theatre group Nixtayolero – “Dawn Star” – in the winter of 1983-84. Doyle was interested in seeing artists who were in positions of political power; but her main concern was for the idea of a social function for art, which she discovered already articulated in the work of Alan Bolt, playwright, dancer and director of Nixtayolero.

The film is largely composed of shots taken of the company as it travels and performs in the countryside as well as brief interviews with its members and Omar Cabezas, author and Head of the Political Division, Ministry of the Interior; scenes of Managua nightlife; and various still photographs and film clips from Nicaraguan and North American information services. Doyle used parts of the soundtrack to give her own voice-over commentary and also used subtitles in experimental ways to add graphic emphasis.

As one might expect the interviews centered on the theme of art in society. It became apparent that Nixtayolero does not prescribe art with a unified socio-political “function.”

“We discovered that, in spite of the fact that the political vision of the theatre work we were doing in Leon was the correct one, the mechanisms, the instruments to make it, were not the correct ones. We had to start fundamentally from the popular traditions.” (Alan Bolt)

The political use of art cannot be indifferent to art’s social origins. The use of art to achieve political ends is called propaganda. But what is ‘propaganda?’

“If by ‘propaganda’ you mean giving ideas in which you believe, I’m making propaganda. I believe in this Revolution. I believe in enlightenment. I believe that people have to destroy prejudices… ignorance, stupidity, mediocrity… and if that’s propaganda, I am making propaganda. But I think this is not real propaganda… Propaganda is what these business are doing through television to sell things, to sell illusions for life.” (Alan Bolt)

The loss of Nicaraguan cultural traditions during its period of colonization and modernization is a problem for those who wish to create a self-reliant Nicaraguan society. Bolt and Nixtayolero base their practice on a theory of “collective memory,” a synthesis of group psychology and socio-political analysis, more referential to Jungian writings and social phenomenology than to post-structural paradigms.

Eye of the Mask recorded the audiences at Nixtayolero performances but did not pretend to account for their presence. The political power of this theatre group was demonstrated by another performance – that of the revolutionary children’s movement “Arising Free” whose astonishing choral poem left no doubt as to the effectiveness of the Nixtayolero ‘propaganda’ program. The poem was a passionate militant expression of correct ideas and sentiment for the fatherland, delivered with admirable force and vivacity. “Arising Free” was then seen receiving instruction from Nixtayolero. The meaning was clear. The Association of Sandinista Children of Matiguas have been inducted into the military through a simple poetic practice. Another film clip showed a Nicaraguan television production called “Only One Army.” This was definitely the ‘bad’ kind of propaganda: “Our army is the most selfless, self-sacrificing and disciplined in the all the terrestrial world, because it knows its historical role…” On one hand is the military – meaning the guerilla way of life which presents people with objectives, aspirations, hardships and friendships that are recognizably human. On the other hand, the television view presented by the Political Directorate of the Sandinista Popular Army is on the surface ‘military’ but is actually an expression of state power produced through a military-technological complex that is compelled to share with the ruling hegemony of geopolitics. In that context, Eye of the Mask demonstrates that Nixtayolero has chosen a political art form that is vital and relevant to us, that is a reflection of human mortality and not only an expression of the will.

The critical issue for Eye of the Mask is not the aesthetics of documentary per se but whether documentary is a viable critical form for the socio-political climate in Canada. ‘Documentary’ means a distinct form of propaganda here: is Doyle’s film as socially active as what it purports to describe, or is it really a museum piece and all that term implies? Doyle has correctly seen that documentary, viewed in the context of its own film distribution system, does function socially and critically in relation to such national information services as television. In Eye of the Mask we are presented with still images, produced by North American news agencies that constitute what we take to be a “collective memory” of Nicaragua’s recent history. Doyle comments, “But memories can also be made in reverse.” Memories can be made in reverse, for Eye of the Mask suggests wholes out of parts, where before there were only parts of the whole.

Speech and Representation by Philip Monk

notes on the performance Transcript by Judith Doyle

(unpublished text, 1981)

The history of modernism is a history of progressive loss of content. Modernism’s critique of representation in favour of the immediate, concrete and irreducible established the limits of representability by using the methods of a discipline to criticize itself, what was unique and proper to a medium asserted itself in all its positivity. Modernism sustained itself in this self-criticism, and its history became a repetition of the form of a critique; but it reproduced itself as this form, never as what was representable within its own limits. Even phenomenology, in its concern for the contents of experience, repeated the empty form of a presumed presence; as much as phenomenology was a “return to the things themselves,” it put the world out of play.

While the exercise was to conceive what was representable as more than a remainder, in the end, representation as a whole was excluded from this modernist history. The two moments of modernism – the formal-reductive and semiotic-textual – have always rejected representation as synonymous with idealism and have championed what seemed impossible for representation, namely, production and the materiality of the sign. A revalued convention of representation, as an affirmative rather than negative value, however, may take us beyond the reductive exclusions of formalism and the critique-bound orthodoxies of ideological analysis. Rethinking representation as a theory of action may show how, contrary to materialist thought, representation leads to the social.

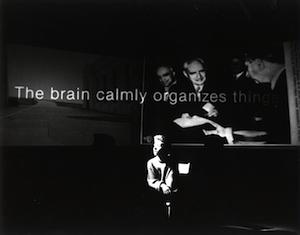

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, multidisciplinary and performance arts opposed themselves to the formalist scheme. Performance art, deriving its formal structure and modes of production from minimal, conceptual and body art, marked a rupture of the event of art by the speaking subject, and hence changed the position of that other subject, the viewer. (While the “dumb,” obdurate objects of minimal art attempted to exclude language, and hence the interpreting subject, language in fact was its suppressed context – i.e., the intentional structure of the work and its gallery context are language dependent). But as in conceptual art, where the introduction of language was subject to the same formalization as any other material, so these new modes first presented themselves as a disjunction between a maintained formal structure and a separately enunciated “content” (when not enacting a reactionary ritualized presence). An interest in narrative and autobiography, mainly by feminist artists, helped distend this formal apparatus and direct work towards representation.

During its short history, performance art has passed from the displacement of the artist in technology (different technological codes fragment and disperse the body) to effacement in representation, in performances where the producing artists are not present, they act more as realizers, or simply operators. In contrast to early performances, these latter are re-performable, which does not make them theatre. While this representational work is “structural” in presentation, in its juxtaposition of, for instance, films, slides, audiotape, and the performer’s speech and body in the real space and time of performance, it is not a closed system. That is, it is not subject to a formal analysis of what is immanent to one medium. Something exceeds – as language, as subject, as history. And that excess must be stated as speech or represented as that which has been suppressed. Or, it does not exceed but is displaced and hence is subject to a system of representation. This dissociation of the codes of presentation – the discrete elements of tape, slides, etc. – does not oppose representation since representation and narrative no longer are subsumed to their traditional transparency. No longer is this work simply a disjunctive juxtaposition of formal materials and substantive content, as speech stands as content, rather something stands for something else (which is not a symbol) and to somebody. When something stands for and to something else, the gesturality of the artist’s presence is replaced by a new subject.

The relation of the representation to its “object” and “user” introduces the semantic and pragmatic dimensions of the work. Thus, representation, neither realism nor naturalism, is also not only a problem of the relation of the reference to the referent: there is not so much a truth value as the effect of figuration within a coherent system of representation. Nor is this work simply depiction, as in representational painting, or what is called “New Image” painting, since the technical means of recording are at hand – the analogue technologies of tape recorders, slides, video, film; it concerns more the structural conditions of representability.

I am not speaking of representation in general, in its universal conditions; I am speaking of contingent or localized representations. The artist speaks from a position, representing it twofold: first, the artist must position himself or herself in relation to that represented, and second, he or she must bring that representation about by the relation of the codes of representation among themselves and to their “content” and reference. Furthermore, in representation we take advantage of a dual reference to art and politics: art and politics meet in that word; and every artistic practice contains a representation of the viewer on the model of political representation. Representation introduces new critical problems rather than regresses to old uncritical forms.

The formal investigation of representation perhaps is now secondary to what is represented, which is not to say that the work is not critical or that these investigations are not part of the artist’s practice or prior to it. One of these new works, the performance Transcript (performed in Toronto in April and September and in Halifax in May), carries its structural conditions even to the level of its title; playing out its etymology helps us to understand the nature of representation in the performance, although the performance is not an illustration of the title. A written copy that usually starts from speech, etymologically “transcript” is a writing across, to the other side, into a different state or place. That is, it bears the same conditions as representation: something that takes the place of another, not necessarily a re-presentation because its form has changed from its origin.

Transcript by Judith Doyle in collaboration with Anna Camera, is based on the spoken accounts of two displacements – one, the physiological displacement of a broken back, and the other, the physical and psychological displacement that is emigration. Thus, while spoken, that is contingent, the displacements already call for representation. Both transcribed texts, spoken in the first person by people the artist knew, were presented and represented in other than their original voices through different means in image and speech. The performance, then, was a play of presence and absence, a representation of material close to the artist but not of her, and a presentation to the audience in the form of these representations.

Constructed in three parts, the opening section of Transcript related the incident of the broken back, the result of a car accident. This transcript was represented in the context of performance by an audiotape in which the artist Judith Doyle reproduced the original speaker’s voice rhythms in a “reading” that coincided with another representation/displacement as a condensation of the text in slides on a screen. Description verged on the edge of representation – of that which is unrepresentable, pain and the reconfiguration of the body, its absences and limits in pain and its boundaries in conjunction with hospital technology. The second part, a text of a Portuguese woman’s experience of emigration to Canada from the Azores, was spoken in performance by her daughter, Anna Camera, an actress who also helped develop this material, and whose speech therefore was another type of reproduction; it concerned an emigrant’s experience of the apparatus of cultural difference – the institutions, customs, technology.

While transcripts imply a work with language in its modes of writing and speech, the third section brought in the texts’ visual references. These images of “original” reference were reconstructed by the artist through slides and press photographs. Not only where these images different from the original referents, they were presented in a way that made this apparent as a mode of representation. (The discourse on representation in general has been established through the figurative visual language of perspective, figure-ground relations, etc.) For instance, in the performance a series of paired slides was projected, angled so that together the two formed a perspective into space. Because one slide was projected into a mirror and then back to the screen, the performer was able to remove part of its image with a hand-held mirror and transport it so that it hovered superimposed on the other image; for example, the head of Portugal’s President Salazar was carried over onto the projection of another press photograph of a Canadian Portuguese group protesting Salazar’s fascism. This move ironically displaced his “Oedipal” authority and representation. Moreover, it created a figure-ground movement that was anticipated in the projection of coloured slides onto the performer in the second section. This manner of superimposition from one slide to another was a type of writing (a trans/script) which left an absence in its origin – the shadow left by the hand-held mirror; representation as emigration from an absent origin. While this narrational series and depiction of event by picking out objects referred to in the text all came from the text of emigration, the formal device brought it into union with its companion transcript: the hovering image was like the description of the moving x-ray machine over the accident victim’s body – an enacted representation. Both texts recorded a displacement of a person put into new cultural and physical configurations with their concurrent “inscriptions.” These displacements were made representative in relation to the artist in her work.

Transcript shares with new work in performance and other media this initiation of a mode of representation outside modernist exclusion, critique or commentary. More fundamentally, Transcript was an attempt to represent what usually is unspoken, in this case, pain and emigration. The material for representation were experiences of those in proximity to the artist: the artist structured and represented the material but created none of it fictively herself. The representation was a position brought forth directly by the use of first person speech, a position which was non-confrontational, representation does not necessarily imply authority.

Overlapping key to house of glass by Adele Freedman

Originally published in: The Globe and Mail, June 16, 1979

Their headquarters used to be the Pilkington Glass showroom on Mercer Street – a magnificent art deco fantasy hidden away between Peter and John streets, at the foot of the Big Needle. Rows of brick glass turn a solid face to the street defying anyone to think that glass is the fragile princess of the material world. Downstairs is a room of elegant proportions fitted out deco-style with a squared-off kitchen set and faded patterned sofas.

The stairwell floats you up to the second floor on smooth sheets of glass, tinted green and slick black and patterned like a jagged cubist collage. Upstairs, more of the same. Lining the walls are four of those glass-panelled, wooden-framed offices you automatically associate with Citizen Kane; and in the corner, a reminder that all of this glass wasn’t manufactured just for show: an enormous walk-in vault.

That cavernous Pilkington money-closet now serves as a storage room for back issues of Only Paper Today and heaps of Rumour Publications, for Pilkington’s crystal palace has become the home of a cluster of artists whose medium is print, pictures and performance. They inhabit their new space as though it were designed for them, and who knows, maybe that forthright entrepreneur Mr. Pilkington even guessed fifty years ago that someday his gleaming glass walls would reflect the images of another generation of entrepreneurs with a product as artistic as his.

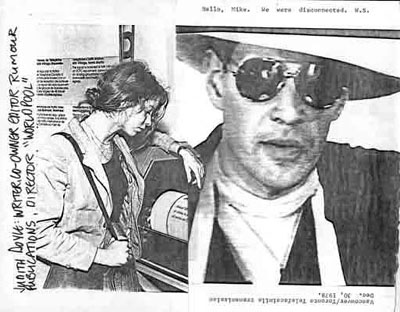

“We’re businesses,” says Judith Doyle, who with Fred Gaysek heads Rumour Publications. “We’re trying not to use the grant structure. (In fact, the opening party at Mercer Street, on May 19th was called “an Anti-Granto Production.”) We’re trying to overlap as much as possible.”

Overlap is the operative word on Mercer Street. Judith Doyle, Fred Gaysek and Willoughby Sharp continue their work with World Pool, a collaboration bent on “networking” artists on a global scale through technology. On International Women’s Day, using the facsimile transceiver lent them by Xerox, Doyle and friends hooked up by image with artists in Boulder, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Pender Island, New York and Buffalo.

Two hundred Toronto networkers looked on as Doyle performed her interpretation of the life of a secretary – at one point she hurled her typewriter into the air – and sent facsimiles of her 12-frame performance to six different locations by picking up the telephone connected to a robot, which turns sound signals into 8-second video scans. “We’re interjecting and exchanging all the time,” says Doyle proudly. “Now we’re trying to devise a way of cost-sharing with New York and Los Angeles. It’s an amazing way of contacting artists.”

For his part, Fred Gaysek is establishing a distribution system for books with a small printing run. Several of them are novel versions of screenplays – written by Doyle under the nom de plume of Norman Fox for Hazleton Motion Pictures. “It’s a bizarre way of making money,” offers Doyle, “but it supports a lot of other projects.” Like the flurry of Rumour titles now available: Brian Kipping’s Memory Drawings, Doyle’s Typewriting, Barry Prophet’s A Book of Humour, Gaysek’s leitmotiv – all printed by photocopy – and Kathy Acker’s sexual travelogue, Kathy Goes to Haiti.

Downstairs at Permanent Press, Paul Collin and Gary Shilling design Rumour Books, print up party invitations and flyers and generally participate in the Mercer Street ethos of low-key survival based on the principal: more for less.

Victor Coleman, the only member of the new community over thirty, continues to publish Only Paper Today every six weeks. He has planned a performance program for the new salon: the June-July series features readings and performances by resident artists, Opal Nations, David Porter and Frances Leeming; Buffalo writers Anne Turyn and Suzanne Johnson; and the intimitable Eldon Garnet.

One of Coleman’s fantasies is to commission a performance series, Homage to Large Glass, created especially for the fishbowl offices. Everything is geared to create a situation where artists can work together comfortably without having to play grant politics. “As men become cheaper,” claims Doyle, “networks become more important.”

Photo taken in 1978 for Only Paper Today (OPT) broadsheet, for a special issue focusing on Worldpool (an artist teleculture network based at 720 Queen St. W. Toronto). From left to right: The Founding Board of Worldpool: Sharon Lovett (community activist), Fred Gaysek (poet, co-proprietor of Rumour Publications with Judith Doyle), Willoughby Sharp (NYC based artist and Publisher of Avalanche Magazine), Judith Doyle, and Norman White (artist, roboticist and OCA Photo-Electric Arts Instructor).

![sarah ann loreth 6[3]](http://mikehoolboom.com/thenewsite/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/sarah-ann-loreth-63.jpg)