• Michaelle McLean interview by Judith Doyle (1985)

• My Life at the Funnel: an interview with Michaelle McLean (May 2013)

Michaelle McLean interview by Judith Doyle (1985)

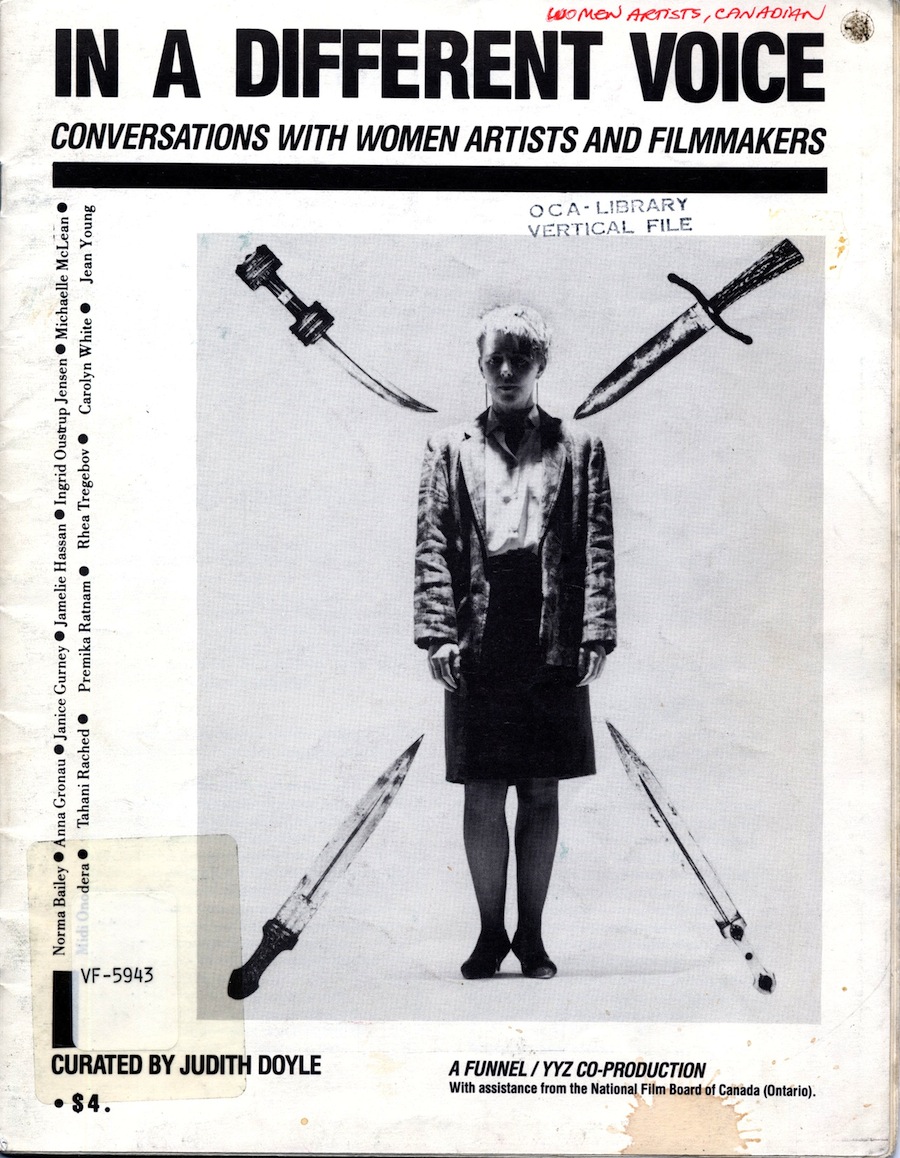

Originally published in “In a Different Voice: Conversations with Women Artists and Filmmakers” by Judith Doyle, published by The Funnel and YYZ, 1986)

Michaelle McLean is an artist and filmmaker. She was born in Toronto in 1953, studied at the Ontario College of Art and has worked as the Director/Programmer at the Funnel. In her film and artworks, she has applied geometric structures to organize intimate, transitory information. The interview traces her current interests in ‘very real magic,’ the power of the filmmaker to access a place by making a work, and the importance of a local community of women filmmakers.

Michaelle McLean: Film is about time and movement, which sounds really corny, but that’s basically what film is. I was in Banff for a year. I was doing a lot of sequence drawings and was interested in positive-negative shapes. It was the spring of 1978, and one of those kinds of fortuitous crashings of fate, because when I came back Anna Gronau was quite involved with the Funnel and I was living in the studio next to her. We had known each other for a long time, so we were very close, and she said, ‘You should come to one of these meetings. This place is going through a political thing right now and it may or may not survive, and I really believe in it.’ So I became involved in this organization because I believed in the heart of these people. They had cameras and equipment, and there were people who could tell you stuff about film, so I started playing around with Super 8.

Judith: What was your first film?

Michaelle: I think I destroyed it. (laughter). Thank God. Well the first one was very simple. I wanted to see what would happen in editing. I had a whole lot of different candles, set them up in my studio and just shot them and intercut them back and forth, on and off, up and down. Behind this I had big ideas about how things exist for a tremendous amount of time but when you perceive them, you perceive only a small part of their existence.

Judith: The films that you made are very spare, minimal and graphic, yet this time in the film there’s more narrative elements. How do you feel about the change?

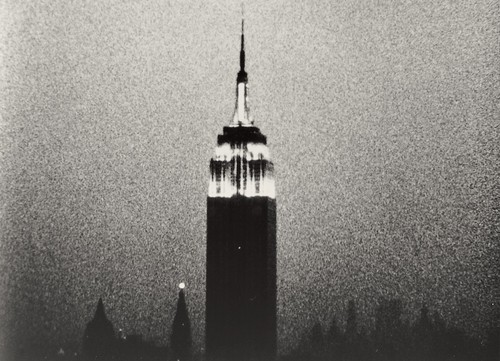

Michaelle: I know from talking with certain people that they feel quite compromised and feel a lot of anxiety about using narrative. But I don’t feel that anxiety at all. One of the reasons I don’t feel that is because the word narrative is huge. When I talk about the narrative element in my work what I mean is that my ideas are clearer. I don’t mean that I’m interested in a story because it goes A,B,C. You put ideas together when you see images come up in front of you. You build something as a viewer. That’s what I call narrative, even if you’re looking at “Empire”— 24 hours of the Empire State Building — that kind of process that happens in the viewer. I’m finding when I put my own work together it’s just the way I’m thinking, my thought process, the connections I’m making, the way I edit my films together. I also think about other people I know, because in a sense, I feel that there’s a community that also understands now the way I think, and I call that a narrative.

Judith: Could you talk more about your sense of community now?

Michaelle: Since 1978, when I started working with film, I’ve been dealing with a community that is specifically interested in what has been called experimental. I loathe the word. It’s a very local community and it’s often women. It’s yourself, Anna, Midi, and occasionally I’ll see another woman’s film that I don’t know, from another part of Canada, another part of the world. But it’s become more specific that way.

Judith: It’s interested to me that, having found this community, you feel more inclined toward narrativity. It seems that it would be more the opposite – ‘I know my community now, I don’t have to use narrative anymore.’

Michaelle: That goes back to what you mean by narrativity. I think the way people use the word is changing and it refers to different things. I feel that the definition for the term is changing.

Judith: I find there are narrative elements, although very minimal ones, in the film of yours in the series, Untitled (1984). Can you talk about it?

Michaelle: There are three body parts and the first is hands but they’re male hands. The man is in control, he’s playing cards, dealing from the deck, and he always throws up the ace of spades. Then there’s a very obvious cut in the film, so you know the filmmaker’s in control. It’s been edited so that he’s always going to turn up the ace of spades. But hands are very powerful and they’re in control. Then you cut to a woman who repeats a movement and it’s very staged. She sits with her back to you and she gets up and turns toward you, but you never see her face, so she’s just this body on parade. And the last one is again just a body part, a head, and he’s the only person that gets to look out at the audience and gaze back at them. It’s about a series of movements that continually repeat and it’s about my emotional response to a woman’s place in society.

Judith: In fact, the image of dealing cards is quoted from other films using narrative. So these elements evoke the sense of narrative film, narratives that we’re very familiar with. Again this kind of cowboy image, this man is dealing the deck with fate, taking the risk of acting, gambling and cheating, but the filmmaker is cheating too. Can you talk about the structure of the piece you’re making for YYZ Gallery? What’s its relationship to your film?

Michaelle: ‘The Subject of Magic’ is less a piece of wall art than it is a frame blow-up from my new film. It will be very obvious that you’re looking at film stills. You’ll get an idea from the two pieces of text of the kinds of juxtapositions I’m trying to play with in this film: the idea of magic, the idea of loss of place, the idea of word play like, ‘Here… hear. This is her voice.’ Because it’s a still image you don’t have a voice but it’s implied that there’s a voice there. Then you have the ‘here’ being either the person who’s reading it, or the image in the photograph of the garden. So, you get a sense of the ideas I’m playing with in the film, and it’s obviously a section from something else.

Judith: Do you think there’s a link between magic and loss of place? Magic often has to do with displacing things, or making reappear in other places.

Michaelle: I’ll tell you about how some of the ideas came to me, and how magic and place tie together. I was interested in the whole idea of invisibility, and invisibility being something that, because of fairy tales and stories, is a magic state, a power that somebody is given. Yet it’s also something that you do to people that is very cruel. We make people invisible, we make the bag ladies invisible, we’ve made women invisible, and all kinds of minority people invisible. It’s a horrible, cruel thing to do. In developing this idea in the film, I wanted to play with that dual idea, of there being power in invisibility and there being power in magic. It’s not a power that’s recognized; people say, ‘It’s just magic tricks.’ In the film, there’s the idea of a place somewhere, that is accessed through something called magic. But, as the film develops, you see that this magic is very real. It gives the people in the film a sense of place and a sense of power.

Judith: What’s the very real magic?

Michaelle: By the end of the film, there are two female voices that come to dominate. You begin to realize that they control the image, so it comes back onto the film medium, in that they’re controlling how its edited. It becomes obvious that these strange edits are controlled by these women, by their voices. And they start to just play with it. The problem of trying to define a place for myself through film – and for me it’s always about my own experience – is very difficult, because I don’t have a place. We could talk about power, we could talk about history, but we don’t have it. So by making a film, you can give it a concrete, tangible place, even though it’s only fleeting. So, it’s making an idea concrete.

Judith: The image of the place, the house of what woman’s place is, comes up in a lot of the works in the series. The metaphor of the ghetto is used for places which are within places, yet outside them. Clubhouses, ethnic bars or restaurants, or the ‘extended families’ are conventional examples of the sites of such ghettos. But the art community is also seen as a ghetto, as are feminist groups. You seem to suggest that the film itself is such a ‘magical’ place, which your community of local women filmmakers share access to.

Anna Gronau, Midi Onodera, Michaelle McLean on set of Anna’s Mary Mary, near Picton, Ontario, 1986,

photo by Michaelle McLean

Michaelle: Over the last few months, when Anna and Midi and I have sat down and talked together about our films, it sounds like we’re all talking about the same film. The ideas that we’re talking about and the things that we’re struggling with, image stuff, or how we’re going to cut stuff, or develop stuff.

Judith: What are some of the things that overlap?

Michaelle: It’s not specific to certain images, but rather saying “I want to be able to put myself into this film, and it’s really about finding an identity for myself. What I’m doing is going into a past that may not be mine, but it’s one that I identify with.” Like, Anna and her Grandmother and Great-Grandmother, and Midi and her Mother and Grandmother, and me – I’m trying to locate it through dreams. These gestures and conversations are aimed towards the past and trying to find roots for our identities. The thing that we’re struggling with is whether it’s appropriate, and whether we’re even able to finish the films. How do you we end the films? Do we, as we’re struggling through this, as women right now, and as filmmakers, are we trying to use these films to answer everything? Or can we make films that leave things open-ended, unresolved?

In my film, there are references made to a woman who disappears who apparently has magic powers. But you’re never really sure. There are questions asked about where she goes, and there are references made to the fact that now she’s gone into the gap, she finds transgressions and she disappears into those. It’s not specifically a history. It’s not a named place or a family line, but there are some images of wild animals, with text over them, that talk about a distant past and a history, and feeling comfortable with a group of people, and there being marvelous things that can happen in the dark, and I can only find them when I’m on the edge of sleep. There are references made to some kind of wild, primitive thing through the use of animals and people.

Judith: Is it a tribal society?

Michaelle: To me, it’s not making reference so much to tribal society as to there being a history that one feels connection with. It’s never actually suggested that an event that someone’s referring to that seems to come from the distant past speaks of a tribe, though viewers could infer that if they wanted, and it’s one of the inferences I would like.

In A Different Voice catalogue (in which this interview with curator Judith Doyle appears), Michaelle McLean’s photo is on the cover

Judith: The second photo-text piece has the image of a shadowy figure surrounded by ritual spears. Your text almost screams out loud at the viewers, saying ‘This one’s for you!’

Michaelle: That’s the piece that came up when we were talking about being BAD. (Laughter). I thought, OK, I’m not going to worry about anything, I’m just going to spit this out. That piece, for me, is just so emotional, so direct, with no consideration of who the audience is. It’s not mediated in any way – well, obviously it is, it’s a photograph – but it’s not like “here is a path, for you.” It’s just like, “Boom.” It makes reference to family, not specifically to Mother. It’s to everybody. It happened when I split up with someone. The image came because of terrible feelings of betrayal. When a relationship ends, when you come of an age when you start to see how the family structure works, all its wonderful parts and its terrible parts. All the horrible social rituals are reinforced and become a trap, even though they are supposedly about bonds, very strong familial or social bonds. They’re a trap. So, this is a very gut response to that feeling. It’s to the family, and it’s to my friends and it’s to my lovers, and it’s to everybody — that feeling of being the target, being betrayed. Actually, what I was thinking I might do is, instead of the ritual spears, is to use flowers with darts on them. (Laughter). There’s a section in my film where I talk about naming things. It says, “Don’t name it! Don’t name it, it will be owned if you name it!” So, the place is never named, the power is never named.

I think that when you speak in a personal language, it connects with many more people. It’s not just a rarified art language or a rarified business language or whatever. I think you cross more boundaries that way than otherwise. The other thing is that, in terms of the progression of my own work over the last seven or eight years, and in particular this one photographic piece that I’m going to do, I feel that my work has always been very personal but I have been conscious, either retroactively or at the time, of how much I’m inclined to veil the personal, because somehow I feel that it’s too vague, but I feel there is a community here that understands the way I think. The personal is in fact not that arcane. I think many more people will understand the piece with the daggers that than the other piece I’m doing. It’s very clear.

Judith: Carolyn (White) was talking about anxiety, and how the male-dominated art world had influenced her behavior as an artist. She found a lot of anxiety in ‘male’ work; it was really tight. She talked in terms of walking around and around her work, looking to see if there was a bolt loose. This circling could result in an anxiety in the work. Do you have feelings of having internalized the anxiety of a male-dominated art world in your work?

Michaelle: Yes, definitely. I look at it and I wonder, why was that? I guess, getting older, you divest yourself of what you used to feel were social obligations. Thank God. That’s one good part to getting old. The other change is working more for a community that I feel stronger bonds with as I know them – you and Anna and Midi and a couple of other people.

Judith: While many art critics seem finished with their need to talk about feminism…

Michaelle: You know, maybe I’m jumping a little ahead of you, but part of the reason I keep referring to women, and one of the things I’ve thought about with this film a lot, is that for the most part, these bonds have been with women. I don’t want to be gender-specific; there are some men that I have a similar bond with, but the specific girlfriend bond… When I talk to women about our work, the ones I have really good discussions with talk about their work with a lot of questioning, a lot of doubt. Other people I talk to – I always feel they’re representing their work to me, they’re not talking about their work. That ties in with, in my earlier stuff, my working hard to veil my heart. I felt that was part of what a work of art had to be. It had to be about representing itself through a system of representation that I didn’t feel comfortable with. It was about distancing yourself from your work. I no longer feel that. In the end, I’ve gained strength from my friends in terms of talking about doubt in their work, about questioning. I think that ‘The Subject of Magic’ is about that a lot. I think the film is about the power of doubt. The dark side of questioning is called doubt in this culture, and it’s not approved of. It’s not considered strength.

Judith: The sense of being a ‘real’ artist is one of presenting a doubt-free, airtight, very polished set of surfaces, that don’t make references to things that can’t be looked up in books.

Michaelle: Named.

My Life at the Funnel: an interview with Michaelle McLean (May 2013)

lightly edited by MM for clarification (June 2013)

Mike: You spent some time at Buck Lake.

Michaelle: I met Anna Gronau at OCA in 1971 (or 72?) and then at Buck Lake, which was a small back-to-the-land commune near Orillia, Ontario on one-hundred acres of forest. Anna’s boyfriend, owned it. After building the A-frame main house and a cold-cellar, and clearing some land they decided they needed a barn. They bought one, and then took it apart, stone by stone, brick by built, and rebuilt it in a clearing. They had cows, pigs and chickens. Her boyfriend was a boilermaker and had to go away for three weeks to make some money, so I went to stay with Anna. It was during the winter and the chainsaw broke, the road was a mile and a half away, and it was several miles down the side road to Highway Eleven to get into town. The house was heated by a wood stove on which all the food was cooked too. We found an old Swede saw and soaped the blade so it would cut through the wood more easily and managed that way. We milked the cows and collected the eggs, and ended up with way too many eggs and milk. For some reason they had a huge stack of Sunday Magazines, the ones that used to come with the New York Times, which were there to be used as fire-starter. Leafing through them one afternoon we found soufflé recipes and realized what we could do with all those eggs and milk! Those three weeks at Buck Lake cemented our friendship. I was eighteen or nineteen, I guess we all were. Buck Lake was definitely driven by a do-it-yourself spirit.

Anna and I had a 125 Roxborough Street connection as well. Jim Anderson and Keith Lock both lived there at different times. When Anna came into town she would stay there sometimes. Jim Murphy — who later found the seats for the Funnel’s theatre on King Street — also lived there and would occasionally show movies in the basement. He was working at a film distributor, more a part of the commercial world, but he loved the energy and inventiveness of the independent film world. He was blessed with a prodigious memory. He could tell you the name of the third dancer in the chorus of a 1946 film.

After a year of art school I went on the road, and travelled to the west coast and into Mexico. I came back to Toronto in April 1978. Anna was going out with Ross McLaren who had started up a small group interested in making and watching experimental films. Anna was working as an administrator at Three Schools, an alternative art school, and right around the corner was a big warehouse building owned by CEAC (Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication). The Funnel held screenings in the basement. I didn’t go to screenings there, I had arrived too late for that, but I went to a meeting about the new organization. They felt they had to move right away. Anna said to me that “We’re going to try to save this place, do you want to help? We’re going to move into a new space and build a theatre.”

Mike: I can’t help noticing that some of the same folks living at Buck Lake and 125 Roxborough Street reappear again when the Funnel starts up. It seems you were circling this scene.

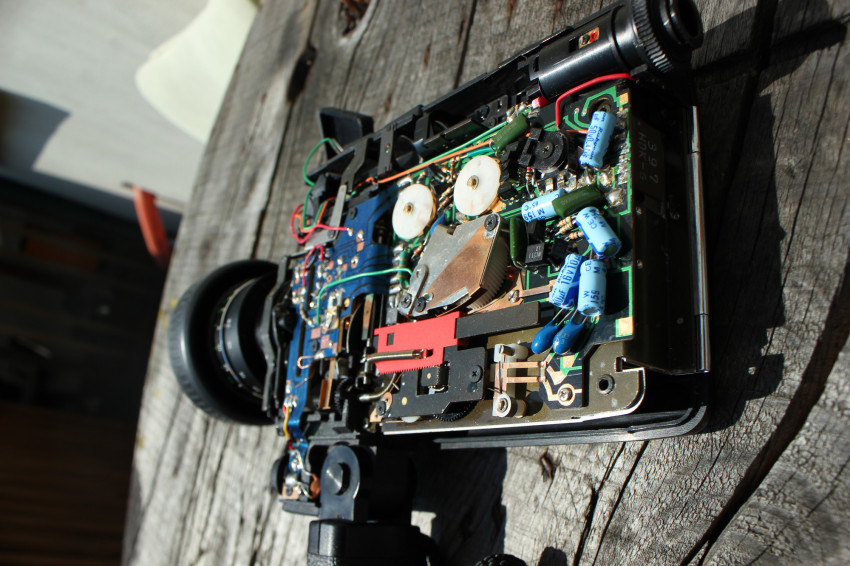

Michaelle: I would never have been involved at The Funnel except for Anna, she was the conduit for me. You get back to town and your good friend is very involved in this new venture, while you’re wondering what to do next. Then away you go, especially at that age. I thought these guys were doing something worthwhile, I was quite happy to lend a hand. I remember sanding and mudding drywall at the Funnel’s King Street location. My lungs are probably paying to this day because of all that drywall dust. There were a dozen of us, including Anna, Ross McLaren, Adam Swica, Jim Murphy, Virginia Kelly (who stole the “Virgin Place” street sign next to the building explaining, “That’s part of my name”), Jim and Dave Anderson and David Bennell, Mikki Fontana and Tom Urquhart. Villem Teder would have been there too. He was our mechanical/electronics whiz and his answer to almost any technical question was, “It depends.” “Can you make it work?” “It depends.” You had a sense you were building something. It was still the hippie era, young people were going back to the land (not only at Buck Lake) and becoming self-sufficient. We were interested in learning new skills, and for us city-folk this might mean growing vegetables or learning how to work a Skil saw and build risers and put seats together. Figuring out the throw of a projector to the screen. How to raise money, how to make a budget. I was twenty–two by then and it was all great to learn.

When I arrived back in Toronto in April 1978 I had been at the Banff Centre working on a series of sequential drawings. As I got involved with the independent film community in Toronto I realized that film is also a sequence of images. My father had an old regular 8mm camera that I dug out of the basement, and later I bought myself a little Canon super 8 camera. I didn’t make films until I got involved with the Funnel. The films were related to the physical gesture of drawing, the camera was like a pencil. I would do things on the ground and film them. They were connected to language and structure.

The Funnel showed films twice a week and I would go regularly. We’d head over to the Dominion Tavern afterwards, and there were cases of beer kept in the darkroom. We were developing our own super 8 and 16mm film. Did we only do negative? There were film labs in town but they were slowly closing. I was already familiar with darkrooms and their smells and what you could do in them because I shared a darkroom with my brother when we were growing up. You could go down there and twelve hours would go by while you mucked around with things. It was great.

Mike: Open screenings were held once each month until the Censor Board closed them down. Do you remember them?

Michaelle: I remember their popularity. A lot of people would go. You never knew what was going to show up. I showed my work there, anybody who had something new came around, there was often work fresh from the darkroom. We would take turns being projectionist so we were all pretty proficient with the various equipment. You could show pretty much anything. We made sure we had the possibility to run tape loops, there were super 8 and 16mm projectors, and microphones if people wanted to narrate their films. We did question and answer periods after formal screenings with invited artists, but during open screenings we’d let the work roll. The feedback was more informal.

Mike: You sat on the very first board.

Michaelle: Anna must have encouraged me to be on the board. It seems to me we were all on the board forever. Ross ran the organization with Anna, I don’t think he could have done it without her. And then Anna succeeded him as the director and I became the office manager. What didn’t we do? We cleaned the toilets, swept the office and theatre, wrote the grants, made the coffee, booked the artists. The grants were written up on the typewriter. You’d spend days typing and working with glue sticks, cutting and pasting parts of past grant applications — and then photocopying everything so it didn’t look like you were cutting and pasting.

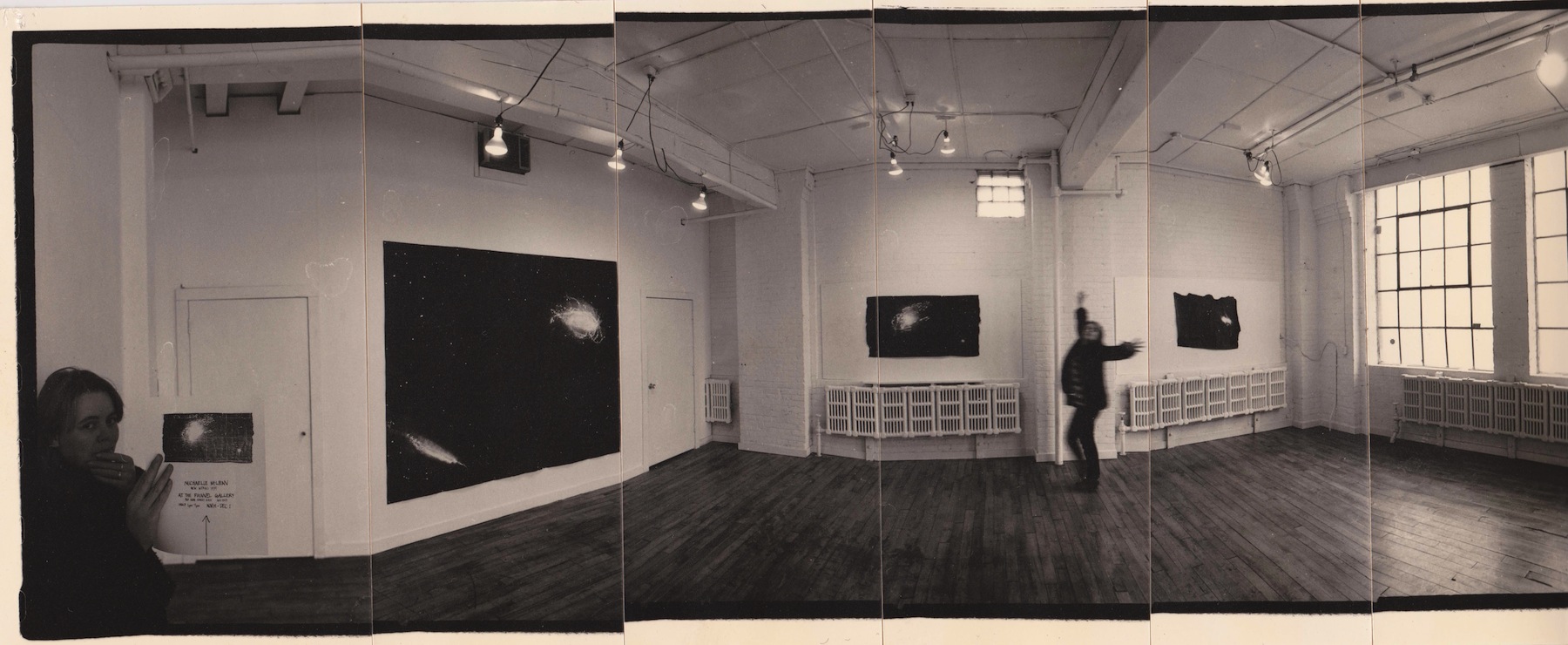

In addition, Anna and I turned our lobby into a gallery. I remember the art collective Fastwurms — Kim Kozzi and Dai Skuze and Napoleon Brousseau — did an installation involving chocolate. They painted all the furniture with chocolate and it smelled like heaven for the first two days. And then for the next three weeks we gagged on the smell as the sun came out and warmed the room. They had such fabulous energy, and were making installations with super 8 films so they were a natural to be in the gallery. I think the feeling about the gallery was: let’s do it because we want to. We weren’t going to be constrained. The artist-run centre movement was in full swing by then, and we all felt that if it wasn’t invented yet, we’d invent it. We were told that what we were doing (experimental film) wasn’t art, and found that the galleries weren’t interested in it, so we decided to just build our own damn galleries and theatres. Fastwurms had that kind of cowboy energy as well. I had a couple of exhibitions of my paintings and collages. Ric Amis had a show of his 35mm still photographs that had been buried in the ground, and then dug up and printed, microbes and all. Rebecca Baird was a Métis artist who worked with Fastwurms and she had a show involving Rice Krispie cacti that stayed up a long time.

Mike: Did the Funnel change direction when Anna became director?

Michaelle: Not that I recall. Anna may remember it differently. When she’d had enough of being Director she asked me to take over. I initially said no, but agreed later. I did it for a couple of years. It was a lot of work for very little pay, but for the most part it was fun. I met a lot of great people, and there was even a bit of travel. I went to Chicago after organizing an exchange with a group of filmmakers there. We were so small, but discovered there were similar outposts around the world, in Japan, New York, Chicago, San Francisco. We ran work from these centres, sometimes as exchanges. They would send a program of their work up, we would send a program of our work there.

Over the years there was a growing interest in artist-run centres. I lobbied the Canada Council to start funding other artist-run centres to include film rentals as part of their exhibition budgets, which meant that we could show our films across the country. The artist-run centre Hallwalls in Buffalo had an ongoing exhibition program, and if they were bringing someone in, we might host them as well. I remember James Benning had problems getting across the border because he arrived with his films in paper shopping bags along with a change of underwear. I guess the custom guards didn’t like the looks of him, but he did eventually show up just before show time.

Mike: How did you program work at a time when it was so difficult to preview films (before video copies were available)?

Michaelle: We didn’t have email, how did we keep in touch with people? We wrote a lot of letters. Do you remember the IBM Selectric? It was a typewriter with a little ball that made typing faster. By reputation really. One would read reviews, talk to colleagues and have phone calls with other centres showing someone’s work. Old school! There was kind of a circuit of filmmakers on tour, so if James Benning was going to be in New York and Buffalo, we would know about it and write him a letter. We received a certain amount of money from the arts councils and spent it on rentals and artist fees. There was no money for hotels so they all stayed on the couch of whoever was the Funnel Director at the time. That would have been Ross and Anna at the beginning, and then Anna, and then myself. I found Ondine (one of Warhol’s superstars) was a great house guest. It was a privilege to have that contact with people.

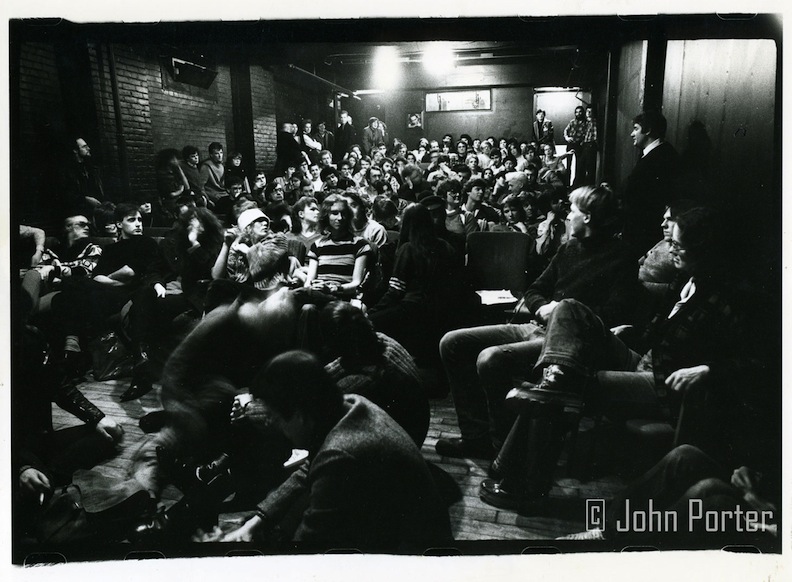

Ondine (standing, far right) presents Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls (1966) at The Funnel, 1980, photo by John Porter

Mike: Did you feel there was a Funnel style?

Michaelle: I remember feeling we were on the outer edges of what was considered film. There was a lot of contentious feeling in the Queen West arts scene. The video makers versus the experimental filmmakers versus the co-op filmmakers. From today’s perspective it seems strange and picayune, but in those days it seemed very important to draw a line and say this is where we begin and this is who we are. We’re doing things differently and we’re not going to be subsumed into something else. There was sometimes an adversarial relation between groups instead of bridge making. Film and video felt very different. They required different machines for production and exhibition and the funding streamed us in different directions. There were separate arts council juries for film and video production. Years later, I left that world and started working at Telefilm Canada and became part of the film and television mainstream of this country. That industry is run on networks and friendships and everyone getting along because you never know who you’re going to work with next. Commercial work is created by teams. The art scene, by contrast, is very much a group of individuals who tend to create alone. This is my crackpot theory. There’s a tendency to draw a line around yourself as an artist — ie: this is how I think, not the way you think — as opposed to developing and imagining larger connections between people. I remember going to a party filled with Queen West artists, and there were only a few who didn’t already know each other talking together. Whereas if you go to a film/television event everybody wants to know everybody else, it’s such a different dynamic.

Mike: There was a lot of discussion about audiences, how to reach more people.

Michaelle: There was never a question of changing the programing. The discussion was rather about how to get media attention to raise our profile. I remember in the very early days at 507 King Street East we put together a mailing list of publications, editors and writers, and mailed out to the list and made tea and coffee and had biscuits. We were going to be open from noon until five and I think one person came. We didn’t yet know how to write a press release. It was typical of the Canadian art scene and the Canadian film and television industry. We made fabulous stuff, but were not the best at getting it to our audiences. I think that’s changed somewhat now, though. Everyone’s more media savvy and better at promoting themselves.

Mike: One of the things that confused me in my early media encounters was watching what seemed like formally conventional documentaries named as video art. In film, distinctions were drawn between experimentalist works and documentaries, dramas, animations.

Michaelle: I wondered about that too, it looks so conventional, why is it called art? At the Funnel we described our work as the bastard child of the art scene and the film industry. Neither wanted us nor understood our work. Video, by a similar definition, would be the bastard child of the television industry and art, but video simply never put itself on that spectrum. Anything that looked conventional didn’t belong at the Funnel. James Benning broke the mold for me because he was an exquisite photographer, his films were made up of still images made magic by the fact that they were on film. But that was as conventional as the work got at the Funnel. We desperately wanted more people to understand our work and had no idea how to make that happen. Or at least I didn’t. And of course we refused to change our work.

Mike: David McIntosh succeeded you as director of the Funnel.

Michaelle: When we met I remember thinking: he’s the guy and I can leave. Someone else knows how to do it. I don’t think he had a lot of patience for the board, and one needed that. It was a democratic, aim-for-consensus organization so if someone wanted to talk, you let them talk, and that meant the meetings were really long. I think that’s what cured me of meetings. (laughs) Didn’t David try and implement new forms of governance?

Mike: David tried to implement an elaborate committee structure, where the entire membership was (self) delegated into a series of committees that would decentralize and sharpen operations. In practice this meant more meetings, and even for people willing to commit every spare moment of their lives, it seemed too much. You were Funnel director for a couple of years, why did you leave?

Michaelle: I got involved in 1978 and left in 1984, that’s six years of cleaning toilets and that was enough. I think I was totally burned out. I had worked seventy-five hours a week without a lot of money in return. I think we accomplished a huge amount, but I don’t think we realized the cost. The concept of burnout just wasn’t there. Maybe it’s youth, you don’t know that there are limits to what you can take mentally and physically. The work fell to too few people. Many people contributed, but if one is cleaning the toilets, and writing the grant applications, and taking someone out to lunch, introducing a screening, doing a question and answer period, taking them out for drinks, taking them home, getting up in the morning… well, there’s only a certain number of years you can do that before you burn out. There was no money to pay people to do more, so we relied on volunteerism, and there are limits to what people can manage. A lot of people got burned out and it didn’t bring out the best in us. There were differences in the art community in Toronto around prior-censorship, and about what defined certain kinds of films and art. Hunger doesn’t make for happy people. It was, even then, an underfunded area, and I think we turned on each other in ways that, if the funding had been healthier, wouldn’t have happened. We scrapped over the little bits thrown in our direction. After David was hired I pretty much walked away from that place. I’d done my time. I also left the Queen West art scene. It was time for something else for me.

My overall memories of the Funnel are very good. I remember there was animosity between some people in different sectors of the Toronto arts community, differences of opinion. Some of that is healthy, because it’s part of defining who you are and what you stand for. But some of it was just because we were all desperately underfunded and hungry.

Mike: Did you feel you were working for a cause, a movement?

Michaelle: Yes, it was the reason to put all those hours in because it was about defining who we were. If we didn’t, nobody else would.

Mike: Was that project of identity linked to a larger project?

Michaelle: I slowly became aware of other artist-run centres in Toronto and beyond. I had arrived through the back door via my friendship with Anna. When I was director I had contact with centres across the country. I gained a larger and larger perspective, and felt we were part of a growing movement. But I was twenty-five then, and maybe every twenty five year old feels that. You’re out there trying to figure out the world, creating the world you want to live in, and finding the things that define you.

Mike: Why is it important to make and show marginal movies?

Michaelle: I’m a gardener. In nature you need diversity to survive. You need many species and plants and seeds to create a healthy whole. That’s why we need little spaces like the Funnel, they provide the diversity that allows the mainstream to exist. For instance, commercial work wouldn’t exist without the margins.