Thinking Pictures: an interview with Judith Doyle (July 2012)

Judith: I went to York University on a visual arts scholarship in 1974, then changed majors to creative writing (a new program headed by the poet Frank Davey. Instructors included Irving Layton, PK Page and W.O Mitchell, as well as Victor Coleman who published Only Paper Today out of A Space. John Bentley Mays who later became the Globe and Mail art critic also worked at York then). My practice was organized around language and performativity. I was in a performance group with Fred Gaysek called Test Patterns; a lot of our work examined language. In our performances Fred and I would speak (like a proto-rap team), or read fragments from our collaborative writing projects. John Kypers played an early Moog synthesizer that belonged to the university, and Barry Prophet operated the slide show. The performances were synaesthetic and immersive. We were techno-focused, and we consistently engaged with the language of technology. Our first downtown performance was at A Space in 1978, when it was still on St. Nicholas Street. My entry into A Space was via Victor Coleman.

In 1978, after graduating from York University, Fred Gaysek, Kim Todd and I rented a storefront on Queen West (where Terroni’s is now) and set up Rumour Publications. We published Kathy Goes to Haiti by Kathy Acker, and a number of xeroxed experimental projects. In 1978, we also started an artist-run telecommunications/teleculture global network called Worldpool with Willoughby Sharp in New York. Worldpool included ad-hoc mix of proto-IT workers, faculty from the Photo-Electric Arts Department at OCA (along with Willoughby, Fred and I, artist/roboticist Norman White was on the Worldpool Board of Directors, and community activist Sharon Lovett). We met at once a week at 720 Queen West. We set up telecommunications exchange events with artists in their studios or collectives other cities. We would send faxes (these took 8 minutes to send each way using a telephone modem. We would send material back and forth, altering each generation through collage and the random and intentional analogue feedback distortions caused by moving the paper around on the drum. The activity could be called proto-Internet art or fax art. Some of the people and places we exchanged with are Judy Rifka and Robin Winters in New York, Bill Bartlett on Pender Island, BC, Hank Bull at the Western Front in Vancouver, and artists in Montreal, Hollywood, Florida and Tokyo. and another in Tokyo, Japan.

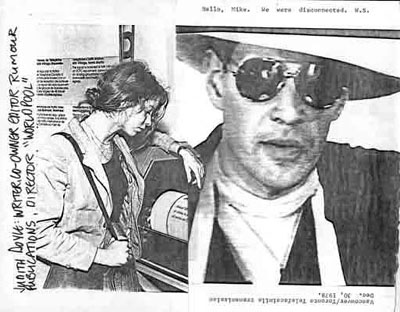

Photo taken in 1978 for Only Paper Today (OPT) broadsheet, for a special issue focusing on Worldpool (an artist teleculture network based at 720 Queen St. W. Toronto). From left to right: The Founding Board of Worldpool: Sharon Lovett (community activist), Fred Gaysek (poet, co-proprietor of Rumour Publications with Judith Doyle), Willoughby Sharp (NYC based artist and Publisher of Avalanche Magazine), Judith Doyle, and Norman White (artist, roboticist and OCA Photo-Electric Arts Instructor).

In the summer of 1978, I interned at A Space. That summer, there was a crucial annual general meeting, what I would call a meltdown, with members from Art Metropole on the one side, and the staff at the time including Victor Coleman and Marien Lewis. The tectonic shifts, the centres of power and influence that were moving at that time showed up as a membership vote of no confidence in the A Space staff that included Marion Lewis on the video side, and Victor Coleman on the overall organizational side, and included the Only Paper Today that was published out of A Space. OPT was a monthly tabloid-format paper including theme issues with interviews, artists projects (particularly photography) and literary writing. After the AGM, A Space moved out of St. Nicholas Street and Victor Coleman moved Only Paper Today into our 720 Queen Street West storefront, where we ran Rumour Publications and Worldpool.

A Space’s structure allowed people to become members by paying a membership fee; members could simply vote out the old. If I recall, there were financial issues that were addressed at that pivotal AGM, but more importantly there were key aesthetic differences. You have to remember that by this time A Space was receiving a lot of federal and provincial funding, and there would have been a desire to access that funding to undertake a different curatorial strategy. A Space had been defined as a downtown gallery, with a clubhouse run by Victor, and a video collective headed up by Marien.

Mike: Lisa Steele was part of A Space’s video efforts in the early 1970s. Was she still part of the video mix?

Judith: No, I believe she was involved with the group that pulled their videos out of distribution at Art Metropole and eventually formed Vtape. This group included Colin Campbell, Clive Robertson, Rodney Werden and Susan Britton. They were the anti-Funnel, the centre of difference. If the Funnel was experimental film, they were video art.

The distinction between film and video was eliminated in the course titles and categories at OCAD University this year. I was instrumental in the process of changing “film” and “video” to “moving images”, and eliminate the fundamental distinction between film and video as disciplinary categories. But while I was growing up, within time-based art practices, film and video were defined as distinctive categories with fundamentally different ideological practices, theoretical approaches, material investigations, and relations in terms of community, agency and identity.

The Funnel founders supported increasingly rigid ideas of experimentalism that kept a guarded distance from video art and documentary media. They were committed to certain lines of practice and interpretation and actively resisted perceived deviation. Understanding this situation in terms of politics of difference might make help make sense of why the Funnel fell apart.

I started out by talking about Art Metropole and specifically General Idea. What General Idea envisioned for A Space was a conceptual model they called a museum without walls. In this model, the organization would curate events in various public venues according to exhibition requirements. This was in distinction to the physical building or gallery-production house, situated within an international network of like-minded places.

Both the “museum without walls” and the artist-run spaces are situated in what Robert Filliou famously called the “eternal network” of artists and artist-run centres (including A Space and Art Metropole, headed by General Idea). The artists created avatar-like, alter-identities for themselves, and curated publications, pageants and gatherings that featured these performative stand-ins. Before that there was mail art, where letters travelled between spaces. Subsequently, different visions of how that network would unfold took shape, and at A Space, Victor Coleman’s insider clubhouse was replaced with Art Metropole’s museum without walls. They moved to smaller digs, kind of an office facility, at 299 Queen and organized exhibitions that often took place in other venues. They wanted to attract new curatorial concepts, and Language and Representation was one of the first projects they undertook. I was close to Philip Monk, the curator of the show, that included my work and also the artists Brian Boigon, Kim Tomczak, John Scott, and Missing Associates. I made two films for the exhibition called Private Property, Public History (17 minutes 1982) and Launch (19 minutes 1982) and they were screened at the Funnel, though most of the show was installed at A Space. The films were commissioned but there were no project parameters.

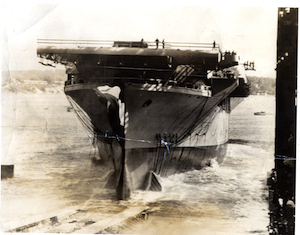

Launch is concerned with the changes in the shipbuilding industry in Collingwood, Ontario. The visuals are a sequence of stills of ship launches over the past one hundred years there. These stills were found in a box at the back of the Collingwood Museum. The voice-over is based on recorded conversations with a shipbuilder, specifically a riveter, whose trade was replaced by welding. The film includes a sequence of stills – no zooms, pans or crops – being side-launched at the Collingwood shipyard. The narration is based in a transcribed interview with the shipbuilder; he discusses the breakdown of the riveting trade and the shipbuilding apprentice system.

Mike: Could you talk about Private Property/Public History?

Judith: I bought a packet of family photographs at an auction sale near my cottage in Wasaga Beach. I could tell they were taken by a woman because she cast her shadow across many of the tiny photographs. These pictures became the basis of a film called Private Property/Public History. As with launch, the film consists of a sequence of images where the photographer casts her own shadow. The film focuses on the gradual erosion and loss of meaning of family photographs. The end of the family is obvious when their collection of photographs is sold at a rural estate auction (the whole farm and contents were being sold). The photos also provided clues about relationships, especially between the photographer and a woman she often photographed. Based on these traces, I returned to the area, found her friends and neighbours, and eventually found her in a nursing home. I recorded and transcribed our conversations, which form an incomplete, associative history, as well as a discourse on photography. When I found the photographer, she was suffering from Alzheimer’s, so our conversations were difficult and circular. There was a palpable attraction between the photographer and another woman that played itself out in these family photos. I asked her who this other person was, and she told me: Villa Reid. Family photographs carry the ideology of the family; when the family dies, the photographs and the speech surrounding them undergo a change of state. This film traces that moment of change, thus the title “Private Property / Public History”. The film was conceived as a pair with “Launch”. Both are concerned about the relation between still and moving images, and between language and image in representation. However, “Private Property / Public History” screened more widely than launch, including on PBS in Buffalo. Both films showed at the Collingwood Museum, as a way of returning to the community.

Mike: Many Funnel members combined performance with film, and you first presented work as a performance artist, didn’t you?

Judith: Yes, I did a performance at the Funnel called Transcript. I did a series of interviews with the artist Andy Patton about the experience of breaking his back. He likened it to cinema in many ways, in terms of tunnel vision and the distance he felt from his own body, and how pain moved in and out of him. I interviewed him for a long time at my kitchen table. I edited what he said by transcribing it all and then cutting the paper into paragraph-sized segments which I arranged on a large studio table. I then taped the scraps together. This was long before the invention of the home computer. I used the cuttings as a script, and referenced Andy’s original voice recordings to try and inflect what he said as closely as possible. I channeled him to generate his voice, his way of articulating specific phrases, his framework of pauses and thought disclosure. In all my films I paid a lot of attention to speech inflection and thought activity for my voiceovers based on transcribed interviews.

The Transcript performance is a recording of my telling Andy’s story, while slides offer text fragments from voiceover. White text on a black background. The second part is a live, spoken word performance by my close friend Anna Camara, based on her mother’s immigration from Portugal to Canada. Anna’s mother, Maria Camara, spoke about flying at night, and her earliest days in Canada. Andy and Maria’s stories both address a physical sense of disembodiment. In the final part of the performance, I worked with two slide projectors, side by side, one projected into a mirror, so they formed a bit of a wing pattern. I took a hand mirror and moved sections of one image so that it was superimposed on the image beside it. The pictures were like the images from flash cards – simple pictures that would describe a word – like a card with the word ‘airplane’ and a picture of an airplane. The images were of items depicted in the transcripts – a picture of a human back, a picture of a plane, all simple images. The two transcripts in the performance were published as a pamphlet by Anne Turyn in Hallwall’s “Top Stories” series in Buffalo, and then adapted into a short film in 1994, The Last Split Second (7 minutes 1998).

Being so associated with experimental film, it should be noted that adaptation and versioning between film, performance, print and installation was a Funnel signature, along with educational initiatives including distribution, publication and workshops.

Andy Patton’s wife Janice Gurney is writing PhD on art and appropriation, including material about Transcript. I haven’t read her thesis paper yet, but I think about appropriation in this sense in terms of reproducing an artwork or in this experiences in a decontextualized way as one’s own. My appropriation strategy was about finding a way into the voice of the person I was talking with. How can I enter this language, including the speech act and an embodied dimension of thinking out loud? I was not an actor, in the sense of trying to personify or develop a character through performance.

If you think of the film projects that you or I would have made at that time, sync sound was not feasible. When voice is present in experimental movies, it is usually in a contrapunctal relation to the image. Voice-over or voice-aside or voice-under, as fits the cinematic project. Experimental film also leverages the sense of scale. In my performance work, I would often stand beside the screen and the scale of projected texts was important in relation to the reader.

I didn’t want the visual focus of my work to be my face or my performance speaking, in the way that video artists including Lisa Steele or Colin Campbell did in their seminal early works (A Very Personal Story, for example, by Lisa, and Sackville, I’m Yours by Colin). Right from the very beginning I usually performed alongside or illuminated by a large scale projection of slides or film, working behind the curtain, rather than having the central visual focus rest on my face. Those are some of the material considerations, but that wasn’t all of it.

At that time my performances had changed from what I had been doing with Fred. My individual practice, the Judith Doyle practice, used language and slide projection and required a cinematic environment to be understood. The Funnel provided optimal conditions, it was frontal and theatrical and dark enough to facilitate both reading and listening. While my work engaged live presence quite a bit, I felt it was cinematic in approach (montage, scale, voice-over, appropriation of images).

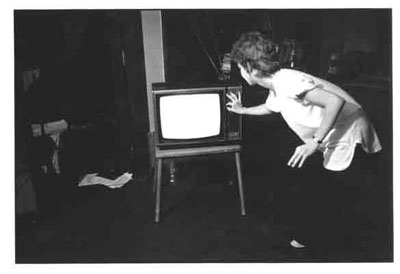

Recently, I’ve been working with artist Emad Dabiri in a collaborative formation that also includes Robin Len and Kang-Il Kim, both of whom had severe brain injuries. Prior to that, both Robin and Kang were media artists who worked with montage and compositing software. The project I recently completed involved a couple of guys who have brain injuries. We’re trying to get them back into animation and compositing because that’s what they were doing before the accidents. The work was shown at Baycrest, a hospital and research centre which revolves around a residential home for the aged. We showed the work on monitors, because the television set generated a sense of embodied engagement for the residents. In that space, flat screens are used mostly for information and advertising.

However, in the late seventies and early eighties, art produced for dissemination on video monitors was distinct from the conditions of film projection. What was important to me about video at that time was sync sound, seeing a person speaking. There wasn’t so much resolution in that early work, but it was crucial to see Lisa Steele or Colin Campbell talking to the camera. Film, on the other hand, produced a dissociation of voice and image, it pulled the voice away, creating a crucial division between body and voice. This was far in advance of the invention of the video projector. Video recording and playback were becoming more affordable, and could be displayed in many venues. Optical printing, cinematic montage, voice-over or wild sound, material investigations we associate with a particular time in NYC – these were a focus – maybe a material entrenchment for the founders of the Funnel.

Now, digital projection and large screen display are ubiquitous in most homes, classrooms and businesses in much of the world. I doubt most of my students could distinguish between material produced on video or film when they see it in class, as they are familiar with digital cinema.

Mike: Why were you interested in the Funnel, Toronto’s underground, home-made, super 8 movie palace?

Judith: For me the Funnel was about a sense of community. It was about sitting through long evenings, like the work of Funnel member Villem Teder who would present us with an hour and a half of emptiness. What was he doing with those images? They were beautifully associative explorations of material and colour with very little sound. Here are some titles: Red, A Circle, Loop with Three Colours, Eyes, Cellular Progression, Incidents from the Trim Bin. I think he was a disciplined filmmaker, but there wasn’t a hint of progression, narrative or even accumulation. It was a big, flat, landscape of time that allowed the viewer to drift in ways that interested me. There was a sense of being in the same space with your friends who were drifting in and out of what he was doing, and then afterwards everyone went out for a drink at the Dominion Tavern and talked about whatever it was that we just did together. There was a strong sense of respect for the filmmaker’s work that we had seen. The artist was often present, and while the crowd was not large, there was an urgent sense of discursive engagement. We took each other’s intentions quite seriously. And we could be painfully jealous of the small gauge feats someone had accomplished, how Villem had produced a certain shade of red in one of his films for instance. It would preoccupy you, you’d be thinking about it a lot. It’s odd because now when David McIntosh or I show films like Michael Snow’s Wavelength (45 minutes, 1967) to students and drag the projector into the classroom and watch what happens to them it’s unbelievable. They have almost no experience of watching something for that long without a break. The sense of time is almost brutal, you feel you’ve committed an act of hostility. Students feel gobsmacked, whacked in the face with time. But without understanding that kind of time-space, I don’t think you can understand the Funnel. The sense of shared duration was part of what created community.

Let’s contrast this exhibition model with video screenings. Yes, people gathered to watch videos together on monitors. The screening would begin at a certain moment, and the artist might be there to answer questions at the end. It wasn’t totally different. But the monitor is not a projection screen. That work wound up at the Venice Biennale, and other major art fairs. Video artists became the international representatives of Canadian culture, they were front and centre in the Canadian art world. Sony Trinitron monitors would be placed on gallery plinths, disembodied soldiers that continued playing in the artist’s absence. Video offered a very different quality of time, and an international network of vangardisms.

Mike: You worked at the Funnel.

Judith: I worked at the Funnel as Michaelle McLean’s assistant and shared the job with Peter Chapman. He did most of the books and accounting, I did more of the grant related research and writing. Each of us had a multi-faceted job.

Mike: Did you attend many screenings at the Funnel?

Judith: Screenings were held on Wednesday nights, and then alternate Fridays or Saturdays. It didn’t matter what was on, you would just go. I don’t recall debating with myself whether something was worth going to or not. You tried to see everything.

Mike: Was that a commonly held attitude?

Judith: There were outlying attendees. Bruce Elder was a member but didn’t come to every show. I think Bruce saw himself as a bridge between the historical New York avant-gardists of the fifties/sixties and the present. I believe he felt he was part of that trajectory. He would be at the Funnel when canonical works of the avant garde would be screened, or when Michael Snow was premiering his new films. Those screenings would attract more of a mainstream art audience.

Every September at the beginning of the season, members were given a three-minute cartridge of Super 8 film to be compiled for the opening night screening. I made a funny one of my mother driving me to the Kodak processing plant on Eglinton north, because as usual I’d left it to the last minute to make the film and get it processed. It played with the Funnel self-reflexive style, films about filmmaking. The small group of individuals who were given 3-minute cartridges and attended the screening of each other’s films, this is the crowd I’m thinking of when I talk about a tight community.

The Funnel was more than a screening facility, it was a distribution centre, a workshop zone, a place where artist-residences were conducted. It offered a wide array of training programs, it was the centre of a healthy zine culture, and had a gallery that showed some remarkable projects. David McIntosh – who I consider to be The Funnel’s most successful director – built on the Funnel’s core to engage a much wider set of communities and participants as Associate Members. At least during the time I was at the Funnel I think of it as a totally integrated system of interdisciplinary collaboration.

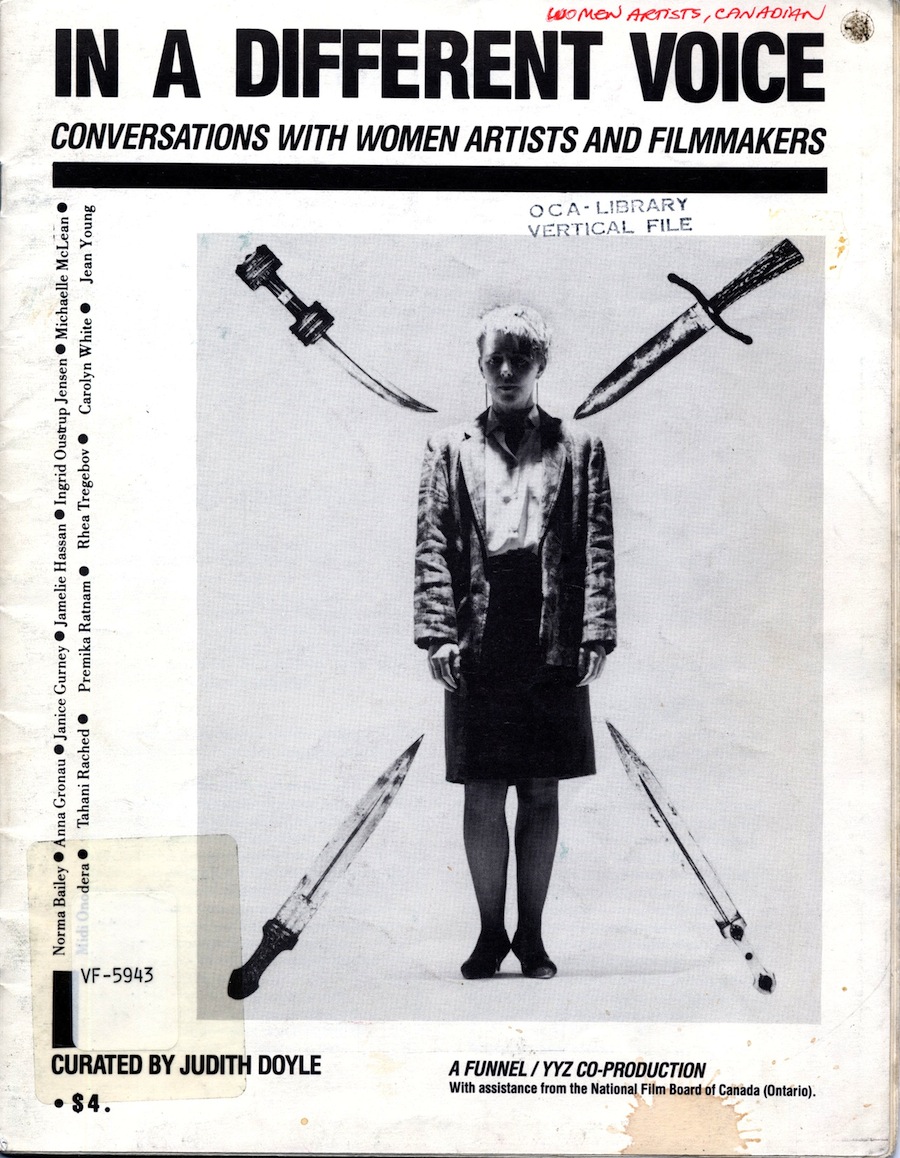

In 1986 I curated a program called In A Different Voice which had a gallery component at YYZ and screenings at the Funnel. It offered a series of films and artworks by women artists, referencing the Carol Gilligan book (In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development) whose argument was that women’s moral development was gender distinct, and that women use language differently when dealing with ethical problems. I did extensive interviews with the ten artists. Working closely with David McIntosh, we edited and designed the catalogue using the very first generation of Pagemaker layout software developed for Mac computers.

In 1986 the Funnel organized a workshop with Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki, a pair of French lesbian experimental filmmakers with a French sense of engaged material sensuality, and a queer politic that didn’t follow the same modes of articulation and investigation as video art. The difference has to do with film’s material realization, the scale, the immersiveness, the sense of being co-present in time, an investigation of the beauty of the image.

They arrived as part of an exhibition called Film Portraits of Women by Women that ran from April 18-May 9, l986. Their all-woman workshop featured Margo Bethel, Laurie Humphries, Cyndra MacDowall, Jackie Rabazo, Paula Saunders, Criss Thompson, Dot Tuer, Wendy Woon, as well as the two of them. Together they created a collaborative super 8 film called Studio Mirrors (35 minutes 1986). Their workshop raised the under-investigated question of generating collaborative structures. I think of artwork as a working surface between myself and the people I am either documenting or collaborating with. At OCAD University now, I direct the Social Media and Collaboration lab (SMAClab). Our research creation activity includes working with people who have completely different specializations. There’s a programmer, a fabricator, and a critic/curator. We’re happy to hang out and inform what we make through this co-presence, seeing what we can make together. I think that was a crucial aspect of the Funnel – we participated so much in each other’s projects. The screenings didn’t begin and end with the films, they were reframed in late night discussions, and these conversations in turn led to collaborative productions and reconsiderations that took many forms.

The Klonaris/Thomadaki workshops had a strong feminist presence that tried to articulate the place of women in experimental film. We were investigating that in the show I curated, In A Different Voice. It featured Funnel regulars like Michaelle McLean, Midi Onodera and Jean Young and raised questions about gender and gender bending. When David McIntosh became the director of the Funnel from 1985-1986, he focused the Funnel lens on the land of gender trouble. David invited former Warhol superstar Ondine for a residency. Ondine was a regular in Warhol’s films and factory studio/home. Ondine toured the college and art-house film circuit with Warhol’s movies. We had fun in Toronto and at the Western Front in Vancouver, where I made a video with him about his fascination with Maria Callas called Gilt Feelings. If Ondine arrived as an ambassador of Warhol’s queer performativity, he was also a reminder that the drag/camp/queer momentums that had been so vividly portrayed by people like Colin Campbell in the video world had been left behind at the Funnel. As the new director, David McIntosh helped to heat things up at the Funnel in a good way, and if you are looking for the fault lines that led to the organization’s collapse, I think that’s where you can begin to find them, around questions of gender trouble and feminism.

In 1983, I did a performance at YYZ called Rate of Descent (45 minutes, 1983) where I read my text with a framework of scrims, projections and some prerecorded audio. The text weaves a personal history with the story of fourteenth century Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden. Details from van der Weyden’s paintings and text are projected onto semi-transparent scrims so that the images bleed backward into the space. The performance is a reading, recorded and live, with some minimal sonics, to which the slides are cued. In claiming history, a tentative relation is established between myself and van der Weyden, on formal, temporal, subjective and theoretical levels. It was initially run at the Theatre Centre, commissioned by Buddies director Sky Gilbert, then taken into the Power Plant, and artist-run centres including YYZ and the Funnel. It was about a total broken-heartedness. There’s a sense of desire accompanied by a loss of speech, a couple that want to speak to each other only they can’t.

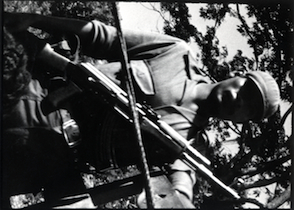

Later in 1983, I joined a revolutionary theatre company in Nicaragua for four months to shoot Eye of the Mask (57 minutes 1985). There were four of us: cameraman, sound operator, translator and myself. We hitchhiked in the middle of a combat zone collecting writing and interviews. When I came back I edited an issue of Impulse Magazine that featured many of the people we had met. I couldn’t afford to process the film, so I got on a train and went to Montreal to visit the National Film Board. I showed them slides and they asked me: what do you need? The footage had to be processed and workprinted, the sound transferred. I got back a mountain of creeping sync craziness and bunkered down at the Funnel with a moviola. Do you remember the moviola? It’s an editing machine operated with a foot pedal, like a sewing machine.

It was the oldest, crankiest piece of equipment, but the Funnel didn’t even have a Steenbeck (motorized editing machine). We borrowed it from the National Film Board, who routinely gave us their cast-off gear. There was no heat at night, so there I sat with my fingerless gloves, trying to work on editing the film. I remember marking up a dissolve with grease pencil when Ross McLaren came strolling through in his usual cocky way and asked what I was doing. I said I was drawing a dissolve on the work print and he said then it’s not an experimental film. Experimental films don’t have dissolves. And off he went to the blue yonder.

This was the orthodoxy pronounced out loud. There was a way you made experimental film, and it could not be a documentary or include dissolves, or engage social issue politics. Eye of the Mask occupies a strange space because it’s not a solidarity movie, it’s about language, as my film work consistently is. I was curious to know if art could have a social function. What happens to a work’s meaning if its purpose is determined in terms of the needs of a community? After the revolutionary take-over in Nicaragua, many poets and artists were appointed to positions of power in the new government. I wanted to know what that meant for their practices and how their art was situated.

I was twenty-four years old, the oldest member of the crew. The theatre group we were following featured people between the ages of nineteen and twenty-four, always on the move. The plays were presented at isolated, woebegone coffee plantations with little regard for how dangerous it was. The crew was shot at more than once. In the film, the performance I tried to reconstruct as best I could with the creeping sync footage was about a flying crab. The purpose of this fairytale was to tell people how important it is to become involved in the revolutionary struggle and not to be lazy and lounge around. The people watching the play were the poorest peasants and coffee pickers you could imagine. When the play ended, they didn’t clap. They’d never seen a play. They had no idea what a crab might be. They had never seen an ocean. The script was imported from Cuba. So there was silence as people stood around wondering, what the hell was that? Then the actors grabbed their guitars and began to play a traditional dance song. With this, a few tentative coffee workers made their way into the little dirt road dividing them from the performers, and danced with the actors. Stephen Deme, our camera operator, captured a lovely actor in a red t-shirt, dancing with a girl. As they slowly turn, the camera reveals he has an AK-47 slung across his back. It gives me chills to think about how this happened in the middle of a war – it was 1984, Reagan had just invaded Grenada. People we filmed died after we shot that scene.

The attitude amongst the old-guard Funnel stalwarts was that if you were making a film with political dimensions in Nicaragua then it ceased to be questioning, experimental, in a space of uncertainty. It was a doomed project, engaged in a secondary relation with reality. The term ‘experimental film’ was deployed to amputate all aspects of narrative and documentary from the space, and to exclude you no matter what your past relationship with the Funnel might have been. If you were working with political and social events, you had traipsed away from experimental filmmaking. You were suspect, a potential double agent who might want to take over the space of experimentalism with competing inappropriate practices.

I had the same thing happen in Trinity Square Video, an artist-run video access centre, by the way. David McIntosh and I were working on a sketch for my feature-length movie Wasaga (90 minutes 1995). We were going to spend a weekend in my Wasaga cottage with David Buchan, the justly celebrated Toronto artist who died at the age of forty-three from AIDS. David and I went to Trinity Square Video to sign up as members and rent a camera to take out for our improvisational weekend. The technician at the time told us we weren’t eligible to join because we were filmmakers and this was a video co-op. We had to get our friend Michael Balser to sneak in and rent the equipment for us. Film and video were entirely separate then. Occasionally you would stick your head out of the trenches and get it banged back down again. So far as the Funnel and discourses of experimental film were concerned, I think that people who were more politically and socially concerned, or engaged with questions of gender and sexuality, fell between the cracks. Of course some famous subsequent experimental film practitioners – Wrik Mead, for example – deeply identified their queer sexuality and experimental film practice. As the new Chair of the whole sculpture/moving images zone of OCAD University, Wrik is engaged in retrofitting experimental film technologies with digital ones.

Mike: Why did you leave the Funnel?

Judith: After the meltdown I didn’t go back to the Funnel again. In 1986’s annual general meeting we had a debate about opening up the membership. The decision was no. There was a clear sense that the direction the Funnel was going in was no longer what the majority wanted.

Mike: Dot Tuer brought forward a motion at the annual general meeting in 1986 proposing that associate members could vote on who could sit on the board. There were ten board spots, and maybe thirty five to forty “full” or “core” members, half of whom had already sworn they would never sit again. So voting for the board really came down to a choice between two or three people at most, if not simply begging or guilting someone to sit again. But even this modest measure was voted down, the “full” members didn’t want to listen to the “associates.”

Judith: That’s what I mean exactly, that was the end of the Funnel. Why do I say that? The direction had been made clear. Who were the associate members? I must have been one by that point. Many associate members had been participating at the Funnel for years. And some had come to occupy queer spaces, politically and socially engaged spaces. This is who was being barred from participating. Why would an organization bar a significant portion of its membership from voting? When you have to entrench a membership in that way, then I think there’s a structural flaw because in a democratic system one hopes to enfranchise as many actively interested people as possible. Were there proxy votes involved?

Mike: The vote was so close that it hung on a single proxy by Villem Teder that he’d granted to chairperson David Bennell, who of course voted against the resolution. The proxy allowed him to vote twice against it. Later on, Villem said that he would have voted for the resolution, but by then it was too late.

Judith: There you are, you see. It’s never good when it comes to proxies, is it? It was the Funnel Board’s loss because there was a very smart group of people with great potential. David McIntosh, Dot Tuer and myself are all people who have distinguished ourselves in the community, we’ve taught generations of students, demonstrated a consistent devotion to experimental film and a total commitment to working in experimental media our whole lives. Why would we be actively excluded?

I remember the intensity of the after-screening debates about what should be screened at the Funnel. What kind of distribution exchanges would occur, who would the visiting artists be? Feminist objectives were pronounced, queercore investigations floated, even the possibility of queering traditional texts. How did Jack Smith put it? Meet me at the bottom of the swimming pool. He had a lifelong self-identification with poverty and writing about artistic exploitation. Can’t we read this as an intersection of class conditions and queer desire? The debates leading to the crisis point weren’t necessarily about the films themselves but how they were framed, how meaning was understood. The old guard at the Funnel may have felt they were losing the heterogeneous space they practiced in since the beginning, but this isn’t exactly true, because when you go back to the antecedents of the Funnel — the open screenings at CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication) — we see a highly politicized space. How did we wind up at the end of the eighties with this cramped and defensive stance, fearing that the true Funnel was going to turn into a hotbed of identity politics? I’m not sure what the fear was. Have you spoken to any of them? By them I mean Ross McLaren. Is he able to articulate now what the concern was then in terms of associate members being allowed to be on the board?

Mike: Ross also felt the vote was crucial, he described it as an attempted coup that would convert the Funnel into a service organization, a “wide open store” which people could use simply because they paid a fee. And he made clear that allowing these “other” people in meant that the organization would lose its identity.

Judith: All I can say about the interpretation of sabotage is that it shows why it was so essential that some of us tried to turn the organization around. How could he? I think of myself at twenty-five, having spent four months in Nicaragua, spent every cent I had, sitting in an unheated room in the Funnel with fingerless gloves on a moviola. What authorizes him to describe someone like me as lying outside the project of experimental film? Not to mention the endless hours – I was a minor bit player but was there constantly. Look at David McIntosh’s massive intellectual contribution, or Dot’s relentlessly intelligent voice and vision. To refer to us as backstabbers speaks of breathtaking entitlement. What were we, maid service?

Who goes to see films at a place like the Funnel? People who are engaged in art cinema, performance, pedagogy, the self-taught movement. It’s a hub of discourses and perspectives. Clearly, it was a place for dykes and fags, for gender bent rangers and people working with the excluded. If the idea is that “the membership” is not interested in other forms of cinema such as narrative, documentary or activist dimensions, well, the world is interested. Every artist-run centre needs to grow and shift in order to stay relevant. It’s the same today. I have students who are making experimental films influenced by Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s work and I see they still have relevance. The Antonioni pan that is very controlled, now must be considered relation to networked cameras and the constant surveillance that is with us at all times. How do these different kinds of cameras change what we understand by the look and being looked at? How does Trinh reframe herself? You can’t just stop asking questions at some point and decide this is what the project of experimental cinema is, because then it just becomes an archive. How did you vote on the associate member issue?

Mike: I voted for inclusion, but didn’t think of it as a turning point. Or did I? At the same meeting John Porter spoke about the need to take a bolder stand against censorship, and I was deeply disappointed that motion was voted down.

Judith: I think it’s interesting that you’re bundling together the two issues that arose at the meeting: censorship and membership. I’m not sure that they have much to do with each other. I think we had to make accommodations with the Censor Board if the Funnel was going to stay in business. There was a period, however brief, when the Funnel wasn’t vilified for complying with the Board. Clive Robertson, the editor of Fuse Magazine, was particularly patronizing and felt the organization was being naive by dealing with the Board at all. But he wasn’t being very pragmatic. The Funnel was a theatre, and hence a very different kind of space than the galleries that showed video. It was a screening space address that could be closed down. The kinds of spaces that Trinity Square Video or Vtape screened in were more like pop-up-shop-type spaces. If it didn’t work, if the screening got shut down by the Censor Board, it could pop up again at the Spadina Hotel for example. Video was pop-upable in a way that film wasn’t.

I was at the Funnel before the blanket censorship exemption forms. Back then, some of the alternative galleries – what we now call artist-run centres – claimed exemption on the basis of being art spaces, alternative galleries, not cinemas. They had the stance that moving pictures circulating in the art world should be afforded different limits than the public cinema system. Because the Funnel was a cinema, it couldn’t really claim it was not a cinema. We were compelled to frame ourselves in the general fray of movie theatres and could not exempt the Funnel as a gallery, as an art zone, subject to different representational jurisdictions, like it or not. So as the Funnel succumbed to engagement with censorship as it was compelled to as a cinema, it withdrew from the specialized status I would now call an “art zone of general inapplicability” which, paradoxically, was one of international art festivals. Thus the Funnel, reluctantly or not, invested itself as part of the fray, in circumstances constraining ordinary local outsiders from artistic exemption.

Because we were in the spotlight of censorship, some of us at the Funnel worked with consciousness and clarity depicting our personal sexuality and the political effects of its representation on a day-to-day basis. There were no queer spaces then for art (unless you count the casting couch with senior artists). For example, my performance Rate of Descent was curated by Sky Gilbert at the Theatre Centre. The Funnel, by virtue of its compromises, became a space charged with sexual politics. The Funnel became a nascent or proto-queer space, a space of feminist sexuality as well, because it was not exempt from the law that bore down on everyone else (queers, diesel femmes, feminists who self-represented sexually) who were bashed, smashed, and muzzled, with no refuge in artistic exemption. There were boundary creatures (John Greyson, Richard Fung) who came to the Funnel, but many of the art potentates at the time were never seen there. I guess I am implying that the repression and censorship that coalesced around the Funnel operated as a magnet that at least briefly transformed the space. These pressures temporarily opened up wider dimensions of political representation, Aboriginal, Latin American… an outsider stance, because the Funnel was paradoxically not permitted to be outside (exempt) because it was a theatre, a cinema, a space for screenings that could be shut down, not a multipurpose gallery or cinema without walls. This came to situate the Funnel and perhaps attract extraordinary people — David McIntosh, Midi Onodera — and subsequently artists including Jack Smith, Ondine, Thomodaki and Klonaris…

The most intensive period with the Censor Board was 1981-2. It’s strange to think about it now because the internet has blown open the question of exhibition. It’s hard to conceptualize a proto-internet space, which artist-run centres to a certain extent engaged in with the idea of the “eternal network,” or “networked conditions between centres.” Since 1994, the dissemination of film has changed so radically the old models are hardly recognizable. And recently conditions have changed again, it seems pointless to speak about the Internet, we’re post-Internet now. By this I mean, there’s no way of discerning the difference between the Internet and anything else now, online and offline experiences are imbricated. But in the late seventies and early eighties, we focused on what a space meant, and how film and video were made possible via that space. It’s a very different context in which we think about the project of the Funnel. It sets into relief the idea that one could control a space, and the dissemination of experimental film.

I think it would be interesting to focus on the performative aspect of the Funnel, rather than the films. Let’s look at the instantiations of performativity, the marginal and temporary events that happened there. They might help to expose the more relational dimension of the place, which I think is important.

The performance work I was doing was cinematic, while Jack Smith’s performances were participatory. I see some of the artist residencies and workshops as performative. I think that some of the art exhibitions were equally transient, I’m thinking of Rebecca Baird’s installation that reworked Western motifs using cacti made out of Rice Krispies. It began to fall apart right away, people ate it between screenings, it was somehow live and ephemeral even though it stood in the gallery. You could look at some of the censorship related discourses and fundraisers and home maintenance constructions as performance. You know how women’s work doesn’t count? There was so much work at the Funnel that didn’t count.

When the Censor Board wasn’t able to shut the Funnel down, we were visited by building inspectors, and of course we didn’t live up to the building code. We had to create a fireproof space around the entire screening space, which required putting paint and insulation underneath the floor. I remember lying on scaffold brushing paint that dripped down in my face, hour after hour. So many volunteers performed an endless series of activities, many related to censorship and the institutionalization of the Funnel as a space. We were not a commercial cinema, and had very little revenue. So when renovations had to be done, we enlisted all the members who had yet to perform compulsory hours of service. Maybe this is why the membership had such a sense of ownership – because everyone had spent so many hours building and renovating the physical space.

I object to the idea that the Funnel was sabotaged by outside forces. The people performing the renovations were members and associate members, some were hangers-on or girlfriends, a lot of people were asked to join in. There seemed to be a lot of struggling between members to control and own the space. Maybe they felt they had sweat equity, that the space belonged to them, not some Johnny-come-lately associate members, but look what they were left with. Without an engagement with the broader community, there was nothing to feed the project.

The Funnel’s performativity was appealing to me, it meant being part of a scene and a public identity. What does it mean when one defines oneself as an artist? Especially if you’re young and you haven’t made any art yet. The statement of claim is a stance. I’m an artist, I’m a filmmaker, or perhaps now, I’m a post-disciplinary artist.

My performance Rate of Descent was about this question of defining oneself and becoming an artist. The claim involves a certain kind of making in public. There’s the first time you show your work, the group show you’re in, the first use of projection or cinematic materials. Perhaps you’ve come from another discipline, or another community background. We did so many things at the Funnel to accommodate that kind of process. Today we’re in a situation where the educational institutions have never been under so much pressure from Conservative government forces to take over education and manage it from the top-down. But what the Funnel generated, along with a number of other artist-run centres, was community-based education. There were workshops and more casual demonstrations, as the equipment manager Midi Onodera trained countless people how to use our super 8 cameras. A very big dimension of the Funnel was allowing people to occupy the space of the artist and define for themselves what their practice was and who it was for outside of the more legitimizing institutional networks. The Funnel was particularly welcoming to engagement with new artists, and operated as a node along a route into larger international art networks.