It Was OK: an interview with Dave Anderson (June 13, 2013)

Mike: How did you get interested in filmmaking?

Dave: I went abroad to study art in Holland from 1967-70, and when I came back to Canada I found myself adrift. I think a lot of people make friends at school and move into the world with those contacts and things progress from there. But I left my friends and contacts in Holland behind. So I went to the Ontario College of Art for a year and met some people. That was when Roy Ascot was president so everything was thrown upside down in terms of curriculum. There was no advanced standing, I had to start over in foundation year even though I’d been in an art school for three years. I stayed for a year and left.

What I studied in Holland was drawing and painting, but that wasn’t part of the current art language. When I got back, nobody was doing it. I remember looking at art magazines showing Lawrence Weiner’s “A Piece of Rug Missing”, Joseph Kosuth’s clocks on walls and photos of Chris Burden having his arm shot with a gun. It was hard to relate any of that to the life drawing I had been doing in Holland, and that’s how I got interested in doing film on the side, wondering where that might lead. And my brother Jim had been making movies with Keith Lock since they were in high school.

Mike: Did you meet Anna Gronau or Michelle McLean at art school?

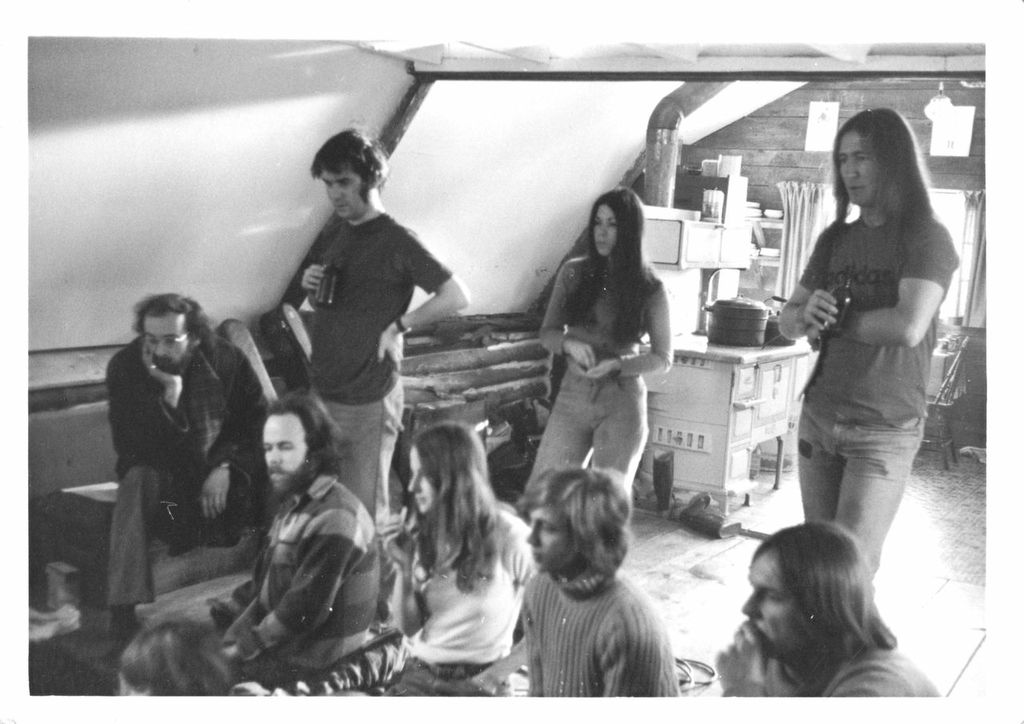

Dave: No, Anna was at Buck Lake (in the bush north of Orillia) with her boyfriend Tom Brouillette. The context for Buck Lake was going back to the land, which was happening in the late sixties and seventies. It wasn’t so much a farming community as an informal collection of artists going back to the land. My brother Jim probably invited me to come. I’d worked as a camp counselor when I was in high school so canoeing was familiar to me and it was great to be out of the city. Tom owned the land, later he converted the barn into a dance studio, and that’s continued to the present day. Tom had found a barn which was taken down and re-erected at the lake, an amazing feat of engineering that we all pitched in to help with. It wasn’t a commune, but there was a sense of collective living. You would drop in and out, that was usual. People would come up and stay for a week and then go back to Toronto. In the winter time you’d have to cut wood and haul water. You’d concentrate on staying warm, maintaining the wood pile or preparing food; everything took a lot longer because there was no electricity. In summer time there was a garden and animals. You did things yourself, you weren’t lolling about, there was always something to do. This is also where I met Michelle.

Mike: Did you see Keith shooting his film (Everything Everywhere Alive Again (16 mm, 72 min, 1974)?

Dave: I’m in it so yes.

Mike: Did that give you ideas of what you might do on film? Did it seem usual or unusual?

Dave: It seemed pretty straightforward, he was making a record of the things happening at the lake. It was a documentation that tried to capture the feel of what it was like and I could relate to that.

Mike: Did his filming offer a permission that these ordinary activities also belonged on 16mm film?

Dave: Why not? I wouldn’t have even asked the question. Keith was very circumspect and careful about how he did his filming. He was considerate and unobtrusive, he wasn’t trying to set up what he was doing as something special, or alter what was happening there. Everyone stayed in an A-frame structure, there was a wood stove in the middle and people slept in lofts at each end. There might be four, six, eight people there at a time, an ebb and flow of comings and goings. I would hitchhike up occasionally. I did spend a week completely alone, because there was a chance to try that. I shot some rolls in regular 8 Kodachrome. After a few days by myself I started noticing things in a new way and filmed a list of little objects. It was the middle of winter and the skies were overcast, so the film turned out very dark. It was more fun when a few others were around.

Buck Lake, Standing left to right: David Anderson, Patrick Lee, Lynn Urquhart, Tom Urquhart

Sitting: Charles Bagnall, Leslie Padorr, Marsha Kirzner, Peter Dudar

Mike: There was a Toronto house at 125 Roxborough that became for a moment the centre of a small film scene. Draft dodger/film distributor Jim Murphy lived there, along with Keith Lock and other luminaries.

Dave: I never lived there but I knew the house well. Jim would bring Hollywood stuff back from work and show it in the basement. I think he was trying to educate us. (laughs) It was also a gathering point for people heading up to the lake.

Mike: Your brother Jim along with Keith Lock made a pair of well received dramatic shorts. Did you have a sense of what you wanted to do in film?

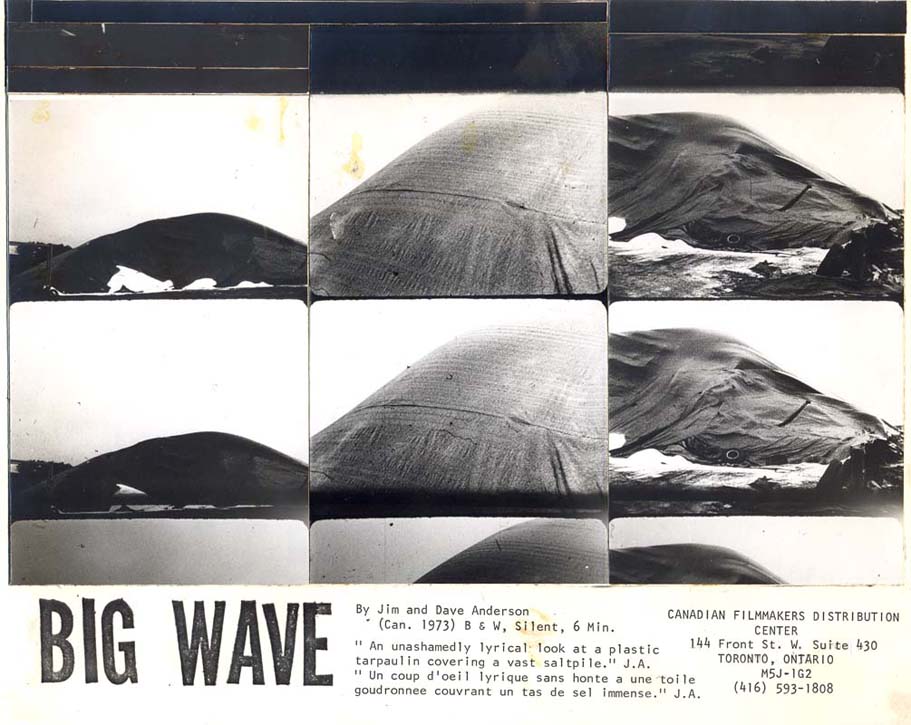

Dave: I made autobiographical films and was interested in the visual world, things I saw, the physical world around me. Big Wave (16 mm, 6 min, 1974) was a record of the salt mounds down at Cherry Beach. The city stockpiled salt every fall to spread over the roads after winter snowfalls. There were big tarpaulins over top which the winds blew. It was a poetic film, silent. You didn’t have to record sound to make a film, silence was fine.

Jim made Gravity is Not Sad but Glad (16 mm, 94 min, 1975). It was an epic feature-length film with sync sound. I appear in one section as a holy kind of guy sitting with my legs crossed saying, “Ommmm.” I think Jim was making fun of a certain meditation trend. That was my part in Jim’s extremely busy set which was his room on Dupont Street, just west of Avenue Road. It was fantastic. It was a small twelve by sixteen foot room in a rooming house that had bay windows looking out over the street. The shelves were bursting with homemade flip books, pictures and drawings were stuck to the wall, objects hung from the ceiling. Everything incorporated in his feature-length film was in that room. In order to get from one side to the other you’d have to walk through little alleyways and corridors.

In the mid-seventies, Keith Lock and I shared the second floor of a building at Adelaide and John. Mr. Freud was the sign painter downstairs who rented the second floor to us. That’s where I made Mr. Signman (Super 8, 23 min. 1978). I shot the whole film from the window or nearby on the street. I would wander down and look at the car wash that the TIFF Lightbox now occupies, or film city crews planting trees and tearing up sidewalks. And of course there were billboards right across the street that became a visual focus for the film, they changed every month.

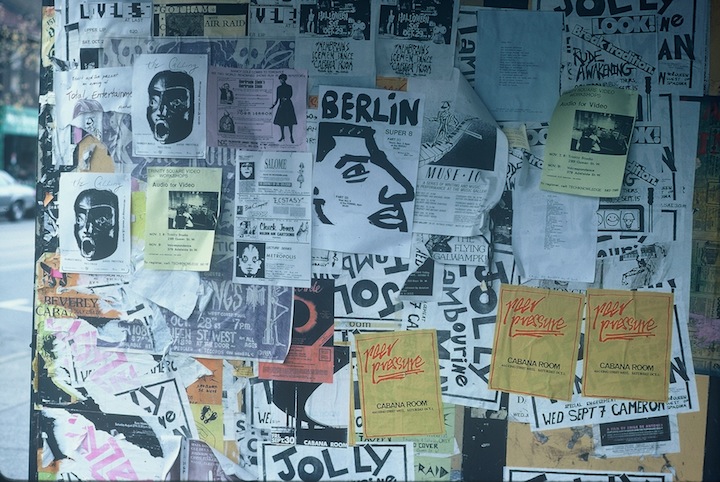

Mike: You decided to run a film series called New Films.

Dave: Keith would have been the instigator of that. The CFMDC (Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre) had a tiny screening room, but I’m trying to think of where else you could show work in the city. Our studio space was suitable because it was long and wide. People sat on the floor, there were some chairs but not enough. One wall had a mullioned glass partition about shoulder height, separating the large room from the room we used as our kitchen. We put the projector on top of the fridge and projected through the glass. We showed Jim’s Gravity, Keith’s Everything and films by local filmmakers. Many were from the collection of the CFMDC. With filmmakers usually present there was an informal question and answer period afterwards. Sometimes filmmakers like Rick Hancox, who were used to talking about their work, would present, but most of us weren’t very used to talking, so the less Q&A the better. The series (nine screenings) ran from February to June of 1977. We didn’t charge admission and we used Mr. Freud’s sign making equipment to make our posters. At that point CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication) started doing open screenings upstairs at15 Duncan Street. Ross McLaren ran the screenings. Even though he had shown at New Films I didn’t really know Ross.

Mike: Ross was making super 8 films, was there a split between artists making super 8 and 16mm films?

Dave: You needed more savvy to make 16mm films. Things like A & B rolls, pulling a print, sound rolls, editing suites, masters, oh my God. It was a bit beyond me, though I did make 16mm films. I would borrow Jim’s Bolex camera and load the camera inside a bag. Doing that was a long way from a super 8 cassette you could just slam into the camera. You also needed more money. For me Super 8 was the way to go.

Mike: What was CEAC like?

Dave: It was a big, open space up on the 4th floor. I don’t remember gallery shows so much, that wasn’t the emphasis. John Faichney curated an exhibition of one-of-a-kind books that I was in. I made books with drawings in them. One was based on going home to Ottawa where my parents lived, I drew the car trip, my mom and dad and their suburban house. I photocopied the drawings and hand coloured the pages with acrylic paint. I had it professionally bound with a hard cover.

Mike: Once again you’re working with everyday moments in your life.

Dave: Yes. In another book I used drawings made on a canoe trip to Quetico Provincial Park with Jim and another friend. Back then there was a lot of talk about acid rain, the lakes were being cleared of every living thing because the pollution coming from the Sudbury mines changed the water’s PH balance. I took the drawings I had made, along with other images, photocopied them and put them together in a little book with a cerlox binding.

Mike: What was your film screening at CEAC like?

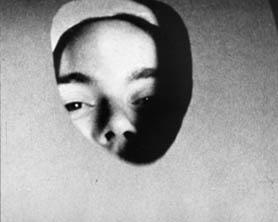

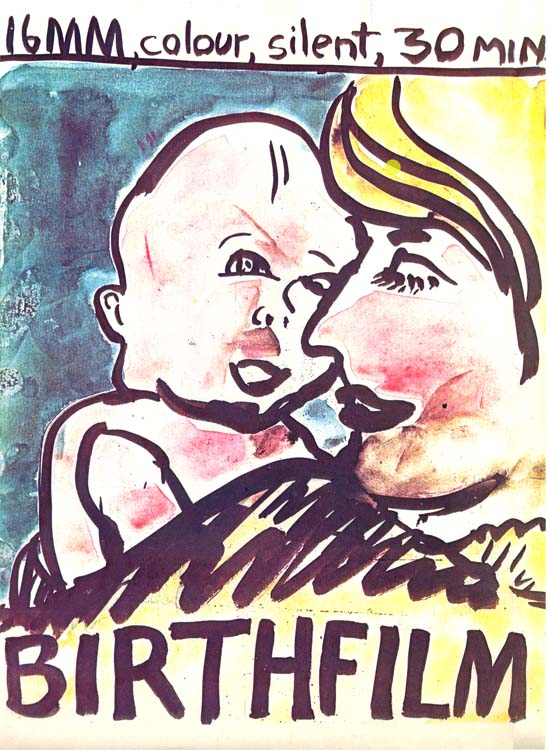

Dave: One of the films I showed was called Birthfilm (16mm, 30 min, 1974). The film started with Jan (a friend) lifting her top and turning in front of the camera to show the changes her body was going through. The idea was to keep doing this to show her body changing as the baby grew. So every few weeks Jan would visit and repeat the same turning or I would circle her with the camera, moves I would have picked up watching Michael Snow films. As we became less camera shy we decided to film the delivery. It was a home birth with a midwife, Jim (the father) and Jan’s mother there. It was intense. It was tough because a 16 mm camera is an intrusive thing, everyone looked at me when I pressed the trigger, it made a lot of noise. But it all went very well. Galen was the baby’s name.

I remember attending a CEAC meeting which had the anarchistic feel of artists versus the corporate world. Ron Gii talked about the injustice of artists having to make money by driving taxis which I was doing at the time. It was a stand-up-and-pound-the-table kind of meeting.

I wasn’t on the inside at CEAC. They published a newspaper, Art Communication Edition which became Strike. One issue featured Aldo Moro, an Italian politician who had been kidnapped by terrorists which was a good thing as far as CEAC was concerned, they supported it. (When the Toronto Sun did a front-page story on CEAC’s views, CEAC lost its funding.)

Mike: The Ross McLaren-led screening room in the CEAC basement was asked to write a letter of support, and in response Ross called a meeting of folks who had been coming out to the open screenings.

Dave: I don’t remember being at the meeting but would have heard about it. That’s when the Funnel moved out of the CEAC basement to 507 King Street East. It was an ambitious undertaking, converting a warehouse space into a theatre with raked seating and a proper (projection) booth. Dave Bennell was in charge of the construction, teaching us about stud walls and 16 inch centres.

Mike: What was the feeling like?

Dave: I don’t know. It was OK. It wasn’t bad.

Mike: It didn’t feel like an exciting, collective project?

Dave: No, not for me because I was always conflicted about art-making directions. I made films but I was also trying to be a painter and didn’t want to be totally diverted, so my enthusiasm would have been curbed. I wasn’t finding huge success showing films.

Mike: What would success look like?

Dave: How about a review?

Mike: Were films getting reviewed?

Dave: Not so much. The CFMDC had a newsletter that occasionally reviewed films, and there was Anna Gronau’s writing in the Funnel newsletter. Dot Tuer was writing as well. That was about it. An artist does something and then it’s over, but there are things like art magazine reviews that concretize these moments, which can then be referred back to, and that’s helpful in creating a trajectory, in creating a sense of direction, what to do next etc. It was a very positive development when reviews began appearing on the backs of the Funnel program posters.

Mike: Were the artists around you receiving recognition?

Dave: I don’t think so, not in a big way. One evening in the year a few people might show at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Jim, Keith and I went to Trent University (1978) with a program of our films. Blaine Allan came by and curated two programs of Funnel work for a Kingston show in 1981. I brought a program of Toronto filmmaker’s films to Cinéma Parallèle in Montreal (1979). That was fun. They had a café out front and seemed to be a little further along than we were. Jim and I went to Hallwalls in Buffalo (1977). It might sound like a big deal now but there could be a year or two between shows and the audiences were small, if there are only five people watching, it lowers expectations.

Mike: Did the Funnel offer a new kind of hope?

Dave: Obviously it did. But building a theatre was only the first step. It needed an organization, some kind of structure, to select the programming and present the films. The Funnel had an active membership. Once a member ($120 per year) you volunteered for the various jobs like being the monthly monitor to make sure the gallery was open, to collect tickets at the door, and sweep floors. We also took turns projecting the films. The film might have been poorly spliced, or insects and leaves may have been stapled to the celluloid but it all had to go through the projector, plus you were often projecting originals. During a screening I’d hold my breath as a thick splice stuttered through the gate or frantically try and blow away a clump of dust with a canister of compressed air (very audible in the theatre!). In spite of our best efforts films would suddenly clatter to a stop. Quick, turn off the projector so the bulb won’t burn a hole in the jammed frame. The theatre, pitch black. Gradually heads would turn around to see what was happening in the booth as you scrambled around. You’d stick your head out the door and say “Just a moment, there’s a little problem.” It was pretty stressful.

Mike: Did you feel it was unreasonable that people had to work so hard?

Dave: No, I think people realized they’d be getting something out of it, making the work worth it.

Mike: Do you remember opening night?

Dave: The euphoria of accomplishment. It’s open! I don’t remember anything about it.

Mike: Would you go see a lot of the shows?

Dave: You couldn’t not go. Especially since the audiences could be small. Every person not sitting in a seat would be missed. It was part of being a good host. You’d come to be supportive of the filmmaker. I remember Villem Teder whose films were abstract, the images distressed by chemical manipulation of the emulsion. I didn’t do that kind of thing myself, but I liked being immersed in it visually. As a painter, seeing someone’s work who was interested in the manipulation of surfaces and the creation of textures was very accessible to me. Villem did all the wiring in the theatre and was also our tech guy, good with the projectors.

Mike: Did you have a show at the Funnel?

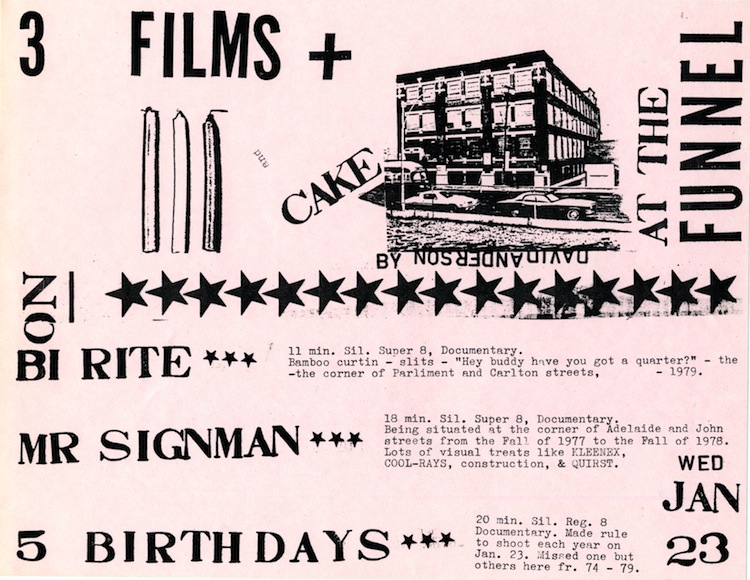

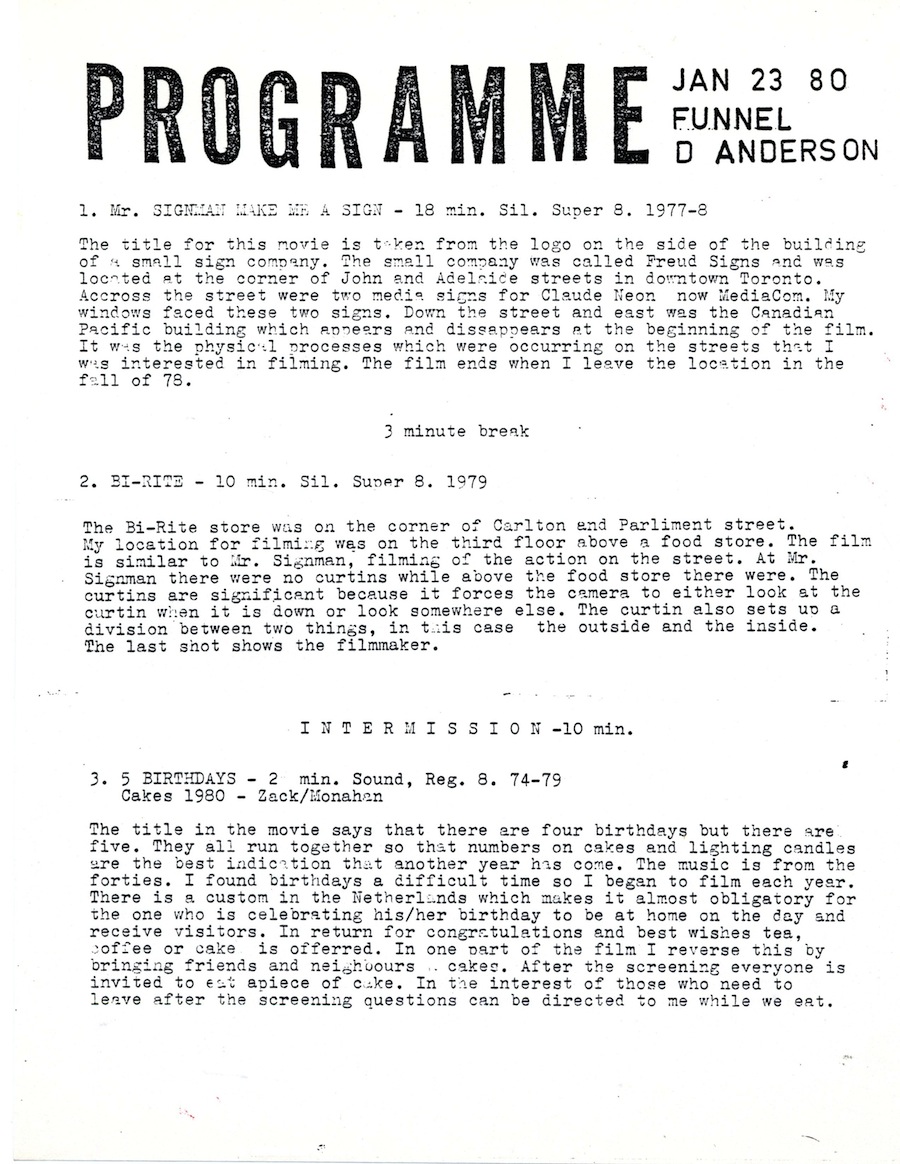

Dave: Yes, on January 23, 1980. I showed Mr. Signman, Bi-Rite and Five Birthdays. For the screening of Five Birthdays I made two tall stands and placed them on either side of the screen. I baked two cakes and put them on the stands. I turned on the repetitive party tape cassette which was played through the theatre sound system and started the film. At some point during the film I moved to the front of the theatre and lit the candles on the cakes. After letting them burn down a bit, I blew them out. Meanwhile on the screen I was doing the same. After the film was over the audience was given a piece of cake.

Mike: Did your involvement with the Funnel slowly fade or come to an abrupt end?

Dave: When did the Funnel stop?

Mike: It ended in 1989.

Dave: 1989! Up until 1983, the year my daughter was born, I was quite heavily involved, especially with the Funnel Gallery. But after 1983 my involvement began to taper off.

Mike: Do you know anything about the move to Soho Street?

Dave: The lease came up, and there was an urge to move because the King Street location was still too remote. But the fight with the Ontario Censor Board during the last years on King Street had tired everybody out. (We were continually being forced to meet new building code requirements.) The move to Soho would mean yet another rebuilding.

Mike: Did the end come as a surprise?

Dave: John Porter became the director after David McIntosh, and John’s firing wasn’t a good sign. John can be rigid about some things but he’s upfront and fair and always had the best interests of the film community in mind. His firing would have made me step back. If you asked what else I was doing in that time, well, I was painting, drawing, and working with photocopy machines and raising my daughter. Starting in l987 we went to Mexico every year. My partner was familiar with a place in the Yucatan and our daughter was going to school there and learning Spanish.

Mike: There weren’t many people at the Funnel who had children.

Dave: No, although I think Peter Chapman and his partner Caroline had a kid too.