Wholehearted: an interview with Martha Davis (July 2013)

Mike: How did you hear about the Funnel, Toronto’s underground movie club?

Martha: I first heard about the Funnel as an “Experimental Film Theatre”, not as an “Underground Movie Club.” I’m not sure I would have joined with a name like that. Although “Experimental Film Theatre” has its own problems, too, and can come off as pretentious. Regardless, I got involved at The Funnel in 1978, the first year it was at the King Street location. I went down to see an open screening. There might have been thirty people there. I had been making films on my own and wanted somewhere to show them. Villem Teder’s movies were the first thing I ever saw, they were abstract and, to me, completely inaccessible. I thought, “Oh God, what is this place about? But there was some other interesting work.

I was in residence at Trinity College but studying film at Innis. It was all theory and criticism, no practice. I didn’t want to go to school to make films because I wanted to discover them on my own, so I just went out and starting making them. The first film I ever made was called Oranges (6 minutes, super 8 silent, 1977). I shot it out the second floor window of what was then Mr. Gameway’s Ark on Yonge at Charles. A bag of two dozen oranges was dropped repeatedly on the street and I filmed whatever happened. It was a kind of street performance, an Allan Kaprow-style happening. I showed that at The Funnel.

Film started for me as series of still photographs. I shot Margaret Atwood opening her eyes in five pictures. I photographed a fat lady laughing, men working on a street excavation. They were like little frames of a movie, like Edward Muybridge’s fragments of motion. So when I saw what film could do, that was it for me. I was hooked.

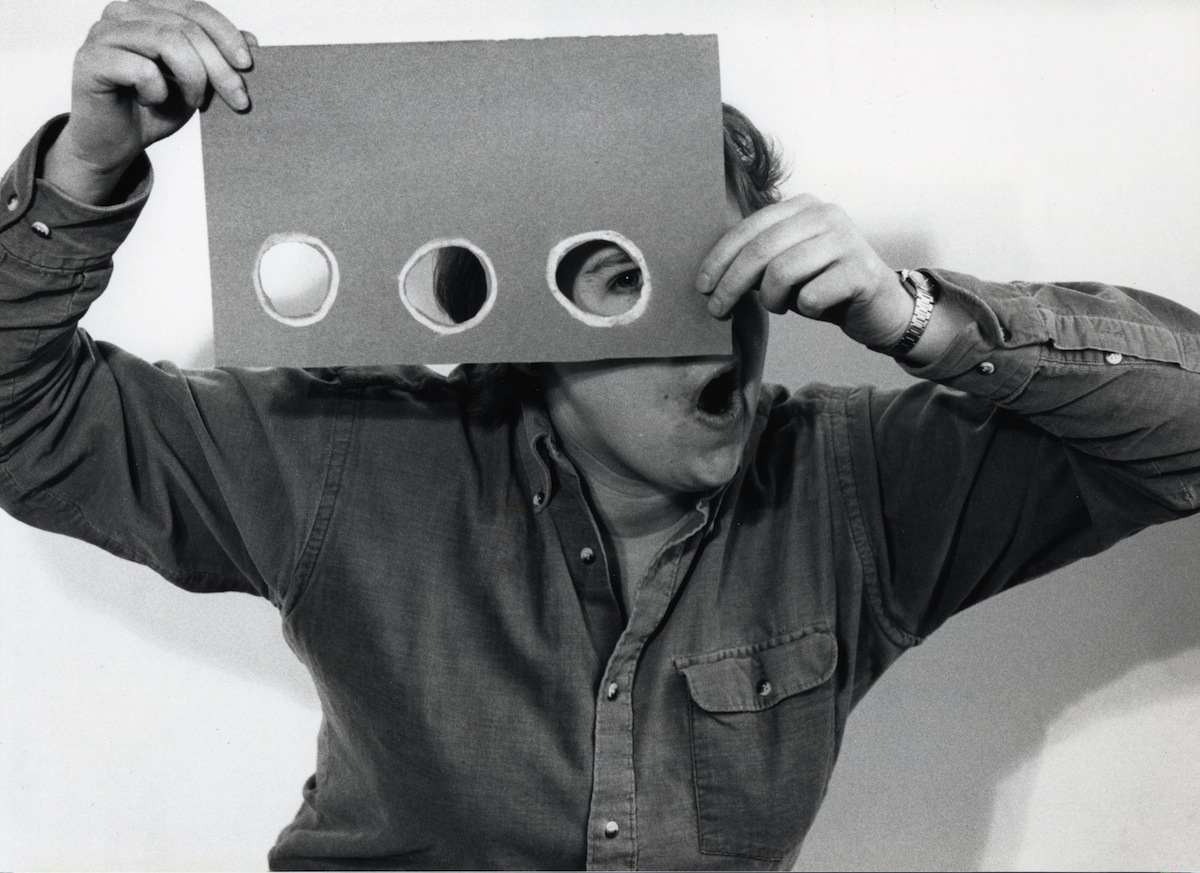

Men With Beards Quartet (24 minutes, super 8 silent, 1978) features a couple of men with beards that I met: Reg and Ernie. I had them eating ice cream, singing Jingle Bells, washing and blow-drying their beards, and picnicking. Each little scenario was shot on a couple of rolls of Super-8 film, all silent. They were portraits. They had identical beards, but weren’t even brothers. I took them to a twins convention and we got kicked out. What a scam!

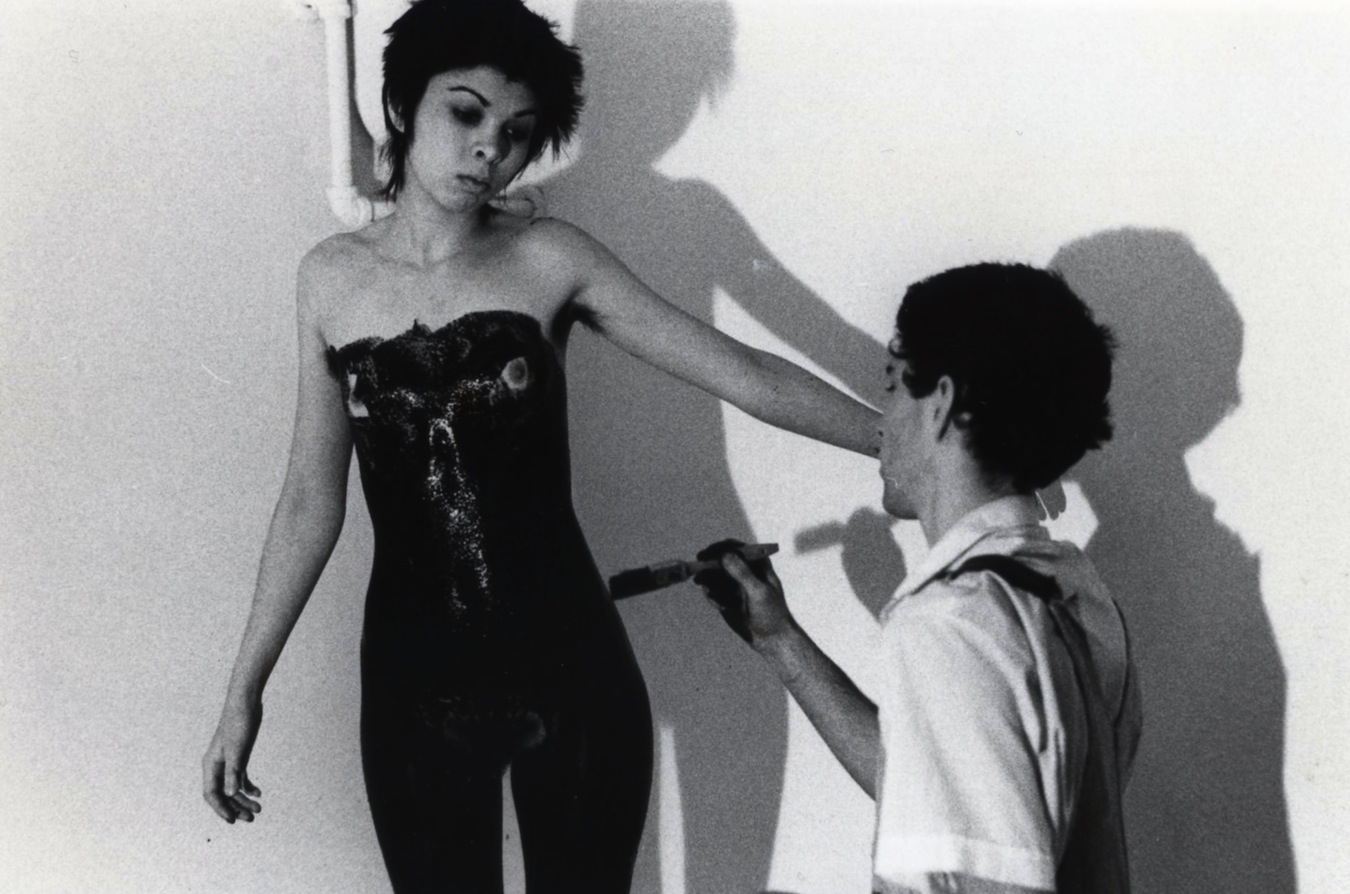

I made Applying and Removing (22 minutes, super 8 silent, 1979) with John Greyson. Do you remember that one? A young woman’s body is painted black, and then she washes herself off in a bathtub, and goes from black to grey to white. We knew a punk girl named Samra who agreed to do it and then there was the question of where we could shoot. I was still in residence at Trinity College, the snottiest college on the face of the earth. But I managed to book an empty residence room with a bathroom and we filmed it there. John painted her with a thick brush and black tempera paint. There was a wonderfully illicit feeling of naughtiness. When the film came out, many people tried to put a feminist reading on it: the enslavement of woman in a male-dominated society, etc. etc. I stayed out of the fray.

John and I hung out that year, and I stayed at his apartment on Queen St. above Madd Ladd’s Furniture for five nights. I had a complete crush on him and it was there, over noodles in a bowl, that he told me he was gay. I remember being so upset. After that I lost touch with him. How sad is that?

Patrick Jenkins and I worked together on Subway (20 minutes, silent, 1979). I filmed it in front of the entrances to four subway stations, two rolls each. It was about the underground and the multitude of bodies emerging from the bowels of the city. I used swish pans that simulated subway movement to connect each of the sequences. We went to Starkman’s Surgical Supply to rent a wheelchair so I could film the pans. I tried out an electric one and zoomed around the store. We got kicked out when I knocked over a whole display case of stomach tubes! Patrick and I had differences of opinion about his use in the film. I’d filmed him emerging from each subway station and he objected to being in every scene. I pointed out that the audience might notice that the same person is coming up every time and this would make it a performance. We had a big fight over that.

I showed all my work as I finished it at The Funnel’s open screenings. Sometimes I felt like I didn’t get much reception. I felt my work was so different from what others were making. Most Funnel films were highly experimental: people drew on film, ripped up the film, showed long movies without people in them. There was upside down stuff, stuff taken from a garbage bin and treated with an optical printer. My work was closer to John Porter’s, who became my hero.

He was always very interested and supportive of what other people were doing. His stop motion miniatures about daily life were quite connected to what I was doing. We went on a hot air balloon ride together, and we each shot films from the balloon. He was working as a letter carrier for the post office when we met and that became my dream job. I graduated from the University of Toronto in 1981, made films for a couple of years on Ontario Arts Council grants, and then became a letter carrier too, where I worked happily for six years part time. Letter carrying for me kept body and soul together and gave me lots of time to make films. I made my feature PATH in those years.

Mike: You made a pair of features in super 8, which was very unusual.

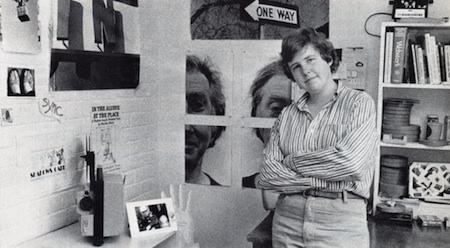

Martha: Yeah, that’s right. First I made In the Alcove, At The Place (94 minutes, 1981). It was a very personal, experiential film about living in a neighbourhood. I went back to “the place,” the same street corner, every two weeks for a year. It had a grocery store, a Hall for rent, a coin laundry and a house. Then there was “the alcove” which was a small space in my co-op house at Innis College, my little student ghetto. The alcove was about as wide as a door, and had a little window in the back. I’d sit in my chair and reflect on “the place” in voiceover. Then I’d go back to “the place” and film a little more. The sections at “the place” got longer as the film went on, and I got to know the people better. The “alcove” always stayed the same length, offering about two minutes of reflection. It filled up with objects from “the place” including photographs of people I’d met, or gifts, or drawings I’d made of it. By the end of the film, the walls in the alcove are completely covered with physical memories of “the place.” And back at “the place,” I was at last invited right into people’s homes to have lunch with them.

Here’s an excerpt from the very first alcove voiceover: “I was riding my bike this morning and had to make a left turn onto Avenue Road. I almost toppled over there in a sudden gust of wind. At the moment I feel pretty harried. I’ve been rushing around all morning. I got up early and didn’t even go out on the balcony to sniff the breeze as I usually do, and then to nearly get blown over in the street!

Today I made arrangements to fly in a hot air balloon with a friend. The incredible feeling of freedom and danger, with nothing around but air. And so high, up to ten thousand feet. Seeing the landscape spread out like a patchwork quilt. Vision from a great distance, extreme long shots. And so still. Apparently you can hear the dogs barking from great heights.

The first thing that happened this morning is that the floodlights which light my alcove toppled over. A few sparks and the lights went out. It’s bright enough outside so that you can still see what’s going on in here. How frustrating though, things never work out quite the way you want them to. Or at least not the way you’d expect them to! That’s part of it, I guess.

Right now there’s a patch of sunlight on my floor, sort of a heart shape, which has shifted in the last little while. I know because it was shining on a pair of blue knitted gloves the last time I looked.”

I premiered In the Alcove, at the Place at Innis College because it was made for an Independent Study course at the university. Then I screened it at the Toronto International Super 8 Film Festival and won second prize: forty rolls of super 8 Kodachrome film. Score!

Mike: There were tensions between that Festival and The Funnel.

Martha: Yes, I’m sure there were. It might have been considered an event for home movie makers. The Funnelites probably turned up their nose at it. But I don’t remember getting any flack from anyone about showing there. It was good to get the free film stock and there was a little bit of recognition that went along with being a super 8 wizardress.

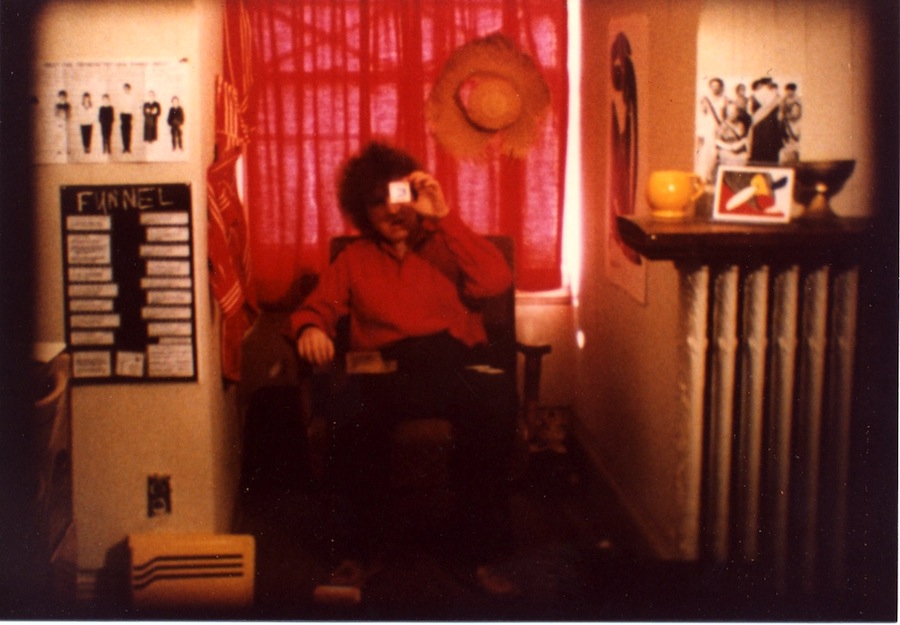

Anyway, my second feature is called PATH (104 minutes, super 8, sound, 1987). Like In the Alcove, it’s a street-based film. Five years in the making, it starts from my house which was at Palmerston and Harbord, and the destination was The Funnel at 507 King Street East. I knew when I started that I would be hiking across town. I’d take a walk once every two weeks, announced in the film by the sound of a gong. I drew a line on a city map, and then travelled along that exact route on the street, filming as I went. I captured many different parts of the city, neighbourhoods and shopping streets, parks and malls, busy and quiet. Then I returned to my house where I’m seen reimagining the walks through what I call maps and models. These are reinterpretations of events that happened on the street. Midi Onodera and Karen Lee filmed those sections. The best parts of PATH for me, in retrospect, are the street events. I run through the Necropolis where my parents are both buried now. I attend a scarecrow festival at Riverdale Farm, I meet a blind man on Yonge Street. I have a little tussle with Hare Krishnas. When I finally arrive at The Funnel at the end of the film I do a little dance in front of the maps. This gestural dance recalls all of the journey’s different sections, and then the film ends.

Mike: Was it important that you shot in super 8?

Martha: It was all I could afford and 16mm wasn’t mobile enough. I didn’t shoot any sync sound, only the occasional wild cassette tape recording. Bill Grove composed the soundtrack and he did a very nice job. Kay Armatage, a programmer at the Festival of Festivals and my advisor for In the Alcove, told me that if PATH were in 16mm she’d “program it so fast it would make my head swim.” So I went down to the National Film Board and asked Silva Basmajian if she could blow it up to 16mm, which she did! I showed up with eight 16mm reels on the day of the preview screenings for the Festival, but Kay still didn’t program it! I was really disappointed.

Mike: Did you feel that the people at The Funnel were your first audience?

Martha: Yes, but I didn’t make it for them, I made it for the joy of making the work, and for myself. The feedback wasn’t so important. If I’d made it for the Funnel it would have been different.

Mike: Did you go to many shows?

Martha: I would usually go once a month for the open screenings, for me they were the most interesting part of the schedule. You never knew what was going to happen at an open screening. I would often bring something to show. I didn’t drink so I don’t remember going out to any bars afterwards, if that’s what they did. I don’t remember hanging out. I’d ride my bicycle down there, and usually it was raining. The building always looked grim, dark and gloomy. It wasn’t a very good location for a film venue: the neighbourhood was deserted, post-apocalyptic even. I was looking for a sense of belonging that I wasn’t finding at the university. At least at the open screenings I was with a group of other filmmakers. It felt good when I went there so I kept going. But I didn’t feel like I had to be there, it wasn’t an obligation, there were a lot of other things happening in my life. Sometimes I felt a sense of community and sometimes not. Good reception or not, I kept creating and remained undeterred.

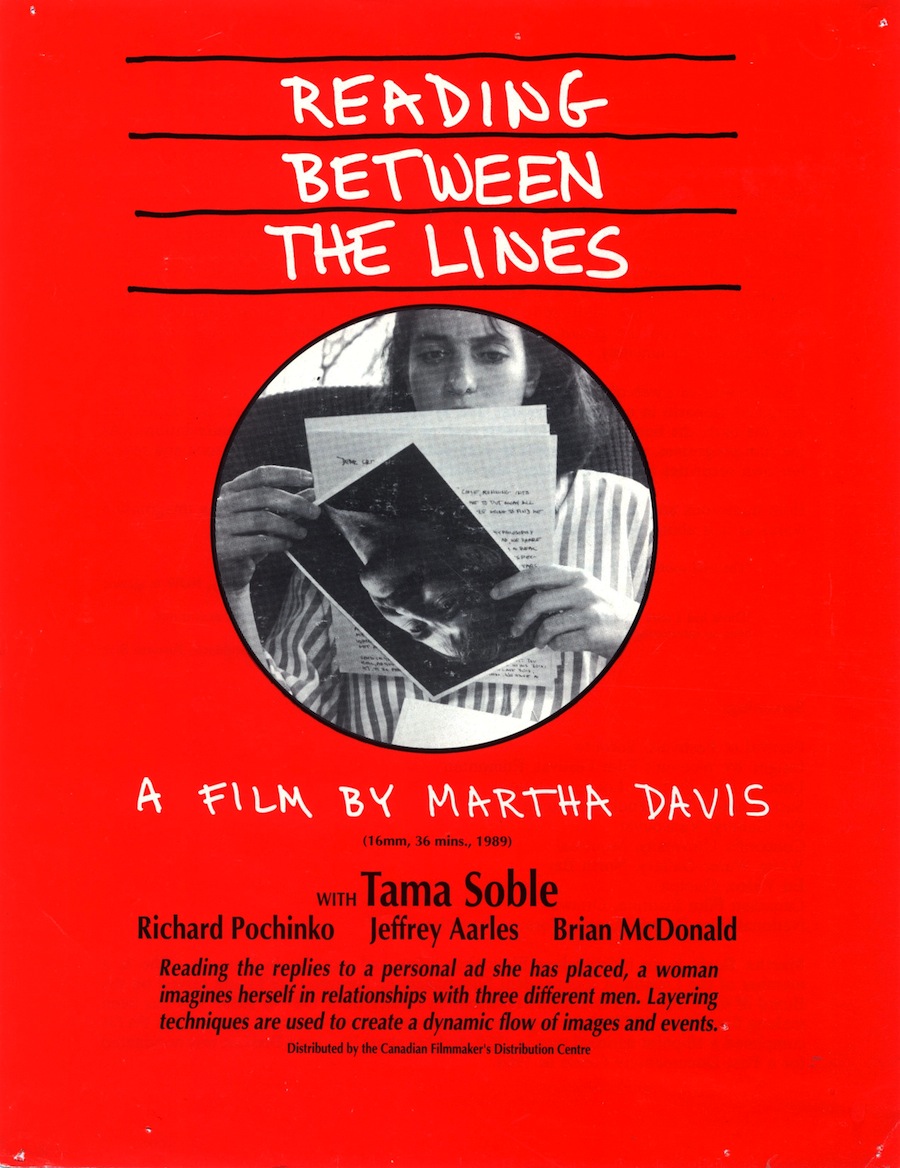

When I showed PATH at The Funnel the theatre was half full, perhaps fifty people. It was better (two years later) after I finished Reading Between the Lines (36 minutes 1989), which I made at LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto). That night was one of the best in my life. It was July 17, 1989 when I premiered it at the National Film Board Theatre on Lombard Street. There were three screenings that night and every one of them was packed. That little theatre also held a hundred people. There was a big problem with the projector, we couldn’t get the optical sound to work, so we had to screen the film with the magnetic soundtrack running in sync at the same time. The sound was gorgeous. What a night.

Mike: Did you have the same feeling of euphoria and relief after you premiered your two features at the Funnel?

Martha: No, at LIFT I had made more friends. It was a different feeling. Being at the LIFT co-op was a better fit for me than The Funnel because even though they didn’t hold screenings, I spent a lot of time there editing. I never made films at The Funnel. It was basically a screening place, it wasn’t really a production space. I remember staying up all night at LIFT working away, and that gave me a feeling of belonging. People were shooting films that were more along my lines, too. Live action, people-centered stuff.

Mike: Was the work shown at The Funnel people-oriented?

Martha: No, it was more concerned with the material itself, and I found the work less accessible. The state of drifting (you called it the “horizontal drift”), of not knowing what I was seeing, it didn’t appeal to me so much.

Mike: Why would you keep going back?

Martha: As I said, I would go to the Open screenings, I wouldn’t go to the long Stan Brakhage, Bruce Elder, Villem Teder screenings. There was variety at the open screenings and new people interested me. Michael Snow’s work always excited me. I didn’t really make friends at the Funnel except for John Porter and Jim Anderson. Maybe Mikki Fontana, Ian Cochrane, Edie Steiner. It was hard to make friends at The Funnel. I always felt a bit disconnected from others because my work seemed more ordinary. I was filming ordinary people doing ordinary things most of the time. The Funnel was almost all guys, too, and I didn’t have much in common with two of the women that were there at the time: Anna Gronau and Michaelle McLean, who were both making feminist work. There was an “inner sanctum” group that made decisions: Ross, Gary, Villem, maybe Jim and Dave, Anna and Michaelle. I was on the Board for a few years, but I never felt I made any big decisions.

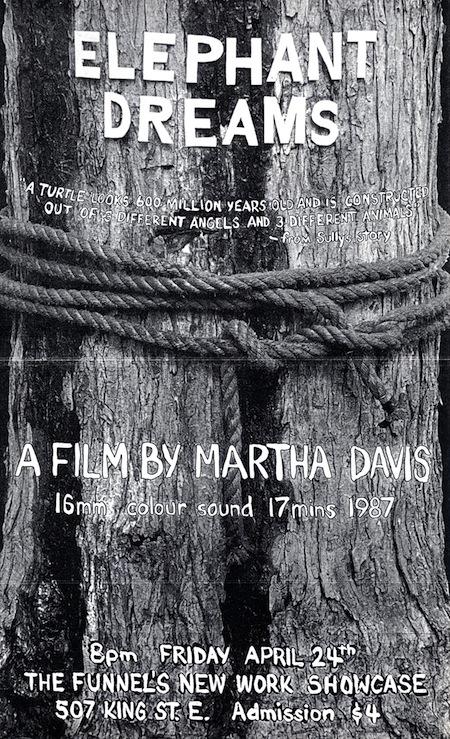

I joined LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) in 1987 after finishing PATH because they had good equipment and I wanted to work in 16mm. Atom Egoyan was a friend of mine from my days at Trinity College and he used to tease me that working in 16mm was where it was at, and that super 8 was for amateurs. I found myself eventually agreeing with him and I wanted to start working seriously in 16mm. I felt I couldn’t do that at the Funnel. There were also philosophical differences. I wanted to make films that were more accessible and less experimental. In 1987 I made Elephant Dreams (17 minutes, 16mm) at LIFT.

The following year I made Reading Between the Lines (36 minutes, 16mm, 1989). Also edited at LIFT. Both Reading and Elephant Dreams were nominated for Genies in the “Best Documentary” category, no less!

By 1987 I’d pretty much left the Funnel and gone over to LIFT. I didn’t go to screenings at the Funnel much any more. I gradually phased out.

Mike: A few years later the Funnel closed. Do you remember what happened?

Martha: As I remember it, The Funnel made a bad move to Soho Street. People thought that they’d get larger audiences if they moved more downtown, but it was far too expensive and they couldn’t afford it. Soho Street was a better location, but I didn’t see them bringing any new members in. There were clearly internal problems before the move around questions of membership and leadership. There was a mega-renovation they tried to undertake which flopped. There were arguments as soon as the theatre opened, too, ongoing tensions within the group about the space and the operating costs. It was all too much. They started in-fighting and the organization fell apart. They were only at Soho for about a year. I see from a poster that I had a one-woman screening there of all my short work, but I have absolutely no recollection of that evening. Isn’t that funny?

Mike: Why was it important for you to make experimental work?

Martha: My particular work allows the viewer to see how memory and association work and how neighbourhoods are created by stories. How communities evolve, how environments change over seasons. Experimental movies show us how we experience our lives and they engage the viewer in an active process and I’m interested in that. I’m glad I made those long, early films. I haven’t seen them in years. I should have a look at them again soon. They’re all housed at the CFMDC, where I was a Board member, too, for a couple of years.

After Reading Between the Lines friends told me that I’d left filmmaking at the apex of my career. They said I should have gone on because I was on the verge of a breakthrough. Reading was more “mainstream,” and with its success I began to feel I might really make my living as a filmmaker. The pull to go into Education was stronger, though, and I “left” to go into teaching. I became a teacher first and foremost because I wanted to share my love of filmmaking with kids. I’d had a blast doing two “Creative Artists in the Schools” projects (OAC) and I wanted to extend this further in the full-time classroom. For the first five years (1993-1998) I was able to make films like nobody’s business. I’d quickly moved to video in my grade three to five classrooms: you shot it, showed it, discussed it, then re-shot it. It was terrific and so immediate. One year I made ten videos with my classes. They learned so much about drama, role play, improvising, being behind the camera, editing, titling. They were super engaged. When I lived three blocks from the school, I used to invite the kids over to my house and we’d have these marathon editing sessions. You certainly can’t do that anymore! Those were great days. Every kid in the class went home with a compilation video at the end of each year. In 1998 the curriculum was changed by Mike Harris, stuffed with things you had to complete. It was very content heavy and gradually I had to let go of the videos. I stopped completely from 2005 to 2010, and in that period became completely out of date with my video technology. I made a short, personal video in the summer of 2010 and since I wanted it to look slick, I worked with a technician at Trinity Square video who edited it on Final Cut Pro for me.

Still photography was my first passion. I’ve gone back to it recently after making twenty-eight videos with my classes in fifteen years. In 2006, after my mom died, I bought a lavish dollhouse. I went straight back to still photography as my daughter (then six) and I wrote and self-published a 120 page book about dolls in this dollhouse. It’s loaded with colour stills. In 2010, we wrote a sequel to our first book, and sold both at “The Word on the Street.” I’ve gone wholeheartedly over to bookmaking with my classes, now, too. My grade twos and threes have made five books together. Check them out at www.blurb.com/b/2735270. (That will get you to one of them—when you preview it you can go to “Author’s Bookstore” and check out all eight I’ve made.) This spring I won the Writer’s Award, a province-wide award sponsored by the Elementary Teacher’s Federation of Ontario for the children’s books I’ve made or helped kids make. That was a great boost to my self-confidence and came with $500! Blurb, the company I publish with, got wind of my class work and paid for every kid to get their own paper copy of our book, “Dogs who Talk.” I wrote a piece on bookmaking with my class which they published online. Go to: http://social.blurb.com/oeS. I still manage to enjoy my teaching for the most part, even though it’s completely mired in bureaucracy now.

My hope when I retire in four years is to work on a mainstream feature film somewhere, in a small capacity. It’s something I’ve never done, and it’s definitely on my bucket list. I have fond memories of the Funnel, though, and believe it’s where I got my start.