It Felt Magical: an interview with Marc Glassman by Mike Hoolboom (July 11, 2013)

Mike: How did you find out about the Funnel?

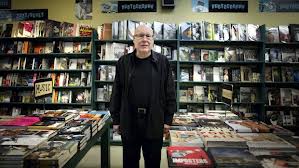

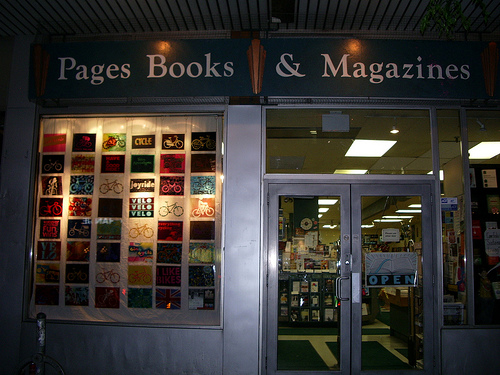

Marc: I started Pages Books & Magazines in September 1979 at 256 Queen Street West, halfway between University and Spadina. It was right in the heart of what quickly became the local art scene but there were only glimmers of it then. I knew I wanted to create something unique with the store. I wanted it to be part of a community: to be lively and responsive to what was happening in the neighbourhood. It turned out that I was in the right place at the right time.

A couple I got to know right away was Carolyn Wuschke and Peter Chapman, who were into books and film and music, much like me. Along with others like Sybil Goldstein, Dick Armin, Jocelyn Laurence, Jayce Salloum, Ann Ireland, John Scott and Peter McCallum, Carolyn and Peter were early regulars in the store. In November, 1979, Carolyn came up with an idea that she would live in the Pages window for a week. She would have black and white filmstrips shot by Villem Teder behind her, she would sit at a black and white checkerboard table with a black cat and a white cat, and she would only read New Directions poetry and novels (which as you remember, Mike, featured black and white photos on their covers). Villem was a member of the Funnel and Peter was working there at the time. I was naive and didn’t know how to attract media attention, until we did this window and got written up by Stephen Strauss in the Globe and Mail.

Carolyn and Peter invited me to the Funnel, which had recently started in their King Street East location. I thought wow, this is amazing. This group of artists had built a theatre by themselves and had created a post-production facility so they could actually make films there. It was such a nice combination. But another thought hit me right away: how are you going to get people to come? What the Funnel was doing couldn’t be more wonderful but what the hell are they doing way out on King Street hidden inside an office building? I had been invited in so I knew about it, but it was like being part of a club. How was anyone else going to know about any of this wonderful stuff except for me and whoever else is invited? That threw me off.

Mike: What were your impressions of the folks at the Funnel?

Marc: I met people in a haphazard way—on Queen Street as well as at the Funnel. I knew who Michael Snow was but didn’t meet him until years later. I met Bruce Elder early on; he was impressive to me because he was a professor. His partner Kathy curated a historical series at the Funnel that I attended. John Porter was taking photographs like crazy. I’d seen him on TV of all places, on the all-night show talking with Chuck the Security Guard. He was living in Nathalie Edwards’ basement on Dunbar Street in Rosedale. Both Michaelle McLean and Jim Anderson did art windows at Pages in the early ‘80s. Anna Gronau seemed really serious to me; I saw her at anti-censorship events. Judith Doyle and I hit it off right away and we became close.

I met Christian Morrison and Ian Cochrane at Pages within a couple of weeks of opening Pages. They were smart and funny — and early members of the Funnel. They were both students of Ross McLaren at OCA (The Ontario College of Art, now OCAD). Christian and Ian decided they wanted to do something else besides looking to the Funnel for programming. They came to me and said they’d like to start their own film society at the art college that would be supplementary to the Funnel. Instead of showing experimental films, they wanted to show everything else—auteur films, animation, documentaries, Hollywood classic genre films.

They said me, “You’ve told us about all these great films that we never see at the Funnel. Would you be interested in doing this program with us?” Of course I said yes. I had done film programming as a student at McGill University in Montreal, but caught the bug again in the fall of 1980 with Christian and Ian and that continued for the next twenty-five years of my life.

The Ontario College of Art gave us the money. We persuaded Dave Andrews, who was heading the Student Activities Committee, to give us a few thousand bucks and we were off to the races. Often we’d show an experimental short before a feature. I programmed a film noir retrospective that started in January 1981 that included Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly, Nick Ray’s In a Lonely Place and Welles’ Touch of Evil. Ian made a fantastic poster and we called our group “Compulsive Cinema.” This was before VHS became big so people had no way of seeing those films. We had a huge hit.

Shortly afterwards Lynne Fernie, who was part of the Fuse editorial board, got me to write an article about Fassbinder. I was back into being a writer, which is what I wanted to be anyway.

I think I became more interesting to members of the Funnel because I was not only someone who had a bookstore and was happy to exhibit art in his window, but was also a film programmer and writer. At that point my relationship with them became more collegial, and I went to the Funnel fairly regularly.

Mike: You were doing events at the Rivoli, too, weren’t you?

Marc: I started programming films at the Rivoli in 1982. We put together a group of people called the Macadamians (because it was an acronym of everyone’s first names). The major people besides myself were Martin Heath, Clark Stewart, Amy Wilson (an artist who was briefly married to Andy Paterson), and all three of the original owners of the Rivoli and the Queen Mother: Andre, David and Annique (Andre’s sister). It formed out to be Macadam, so we called ourselves the Macadamian Film Society. I was able to approach various distributors like Criterion and say we’re film nuts (macadamians, don’t you know?) — just a film society. It was kind of bullshit because we were obviously screening the films to anyone who showed up at the backroom of the Rivoli, but there was a regular rental rate and a much cheaper film society rate, and that helped us break even.

We put on the second event that ever happened at the Rivoli (which had—and still has — a restaurant/patio in front, and a backroom that features bands, comedy, theatre, film and live events). We were on Sunday nights for five years, from 1982-87. Monday nights were Kids in the Hall. We had fun, and I was truly curating. We would toss around ideas and I did what I thought was interesting. I did a series featuring films by Fassbinder and Sirk for a month, comparing subversive melodramas. One of my favourites paired Hitchock and Bunuel as lapsed Catholics. Martin Heath came up with the idea that we should do black comedies in Japan and England, which I called “Island Cinema” – the psychosis of being on an island. For that one, we showed Oshima’s Death by Hanging and the Ealing comedy Kind Hearts and Coronets.

At one point Handsome Ned and I were friends and we decided to put together a series of spaghetti westerns. For ten dollars Ned sang, the Rivoli gave the audience spaghetti dinners and we showed them Sergio Leone westerns. I think we charged $10 an evening but it might have been cheaper. Our screenings offered a potpourri of happiness, including three month-long programs called Retina, which highlighted historical and contemporary avant-garde work. We co-presented those with the CFMDC (Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre) in 1983, 1985 and 1986. Films we showed included Opus 40 by Barbara Sternberg, Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper by David Rimmer (decades before they got Governor-Generals Awards), Standard Time by Michael Snow, Yukon Postcards by Blaine Allan, Sailboat by Joyce Weiland, Hart of London by Jack Chambers as well as films by Kenneth Anger, Peter Kubelka, Paul Sharits and others. It was amazing work and we got good crowds at the Rivoli for each series.

Mike: How did you end up bringing Robert Frank to the Funnel?

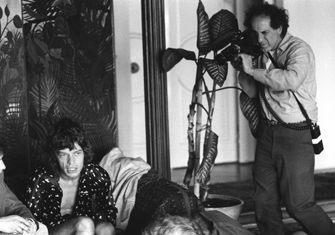

Marc: In 1983 I became involved with the Toronto Group for Human Rights. They had done a series of projects, including The Writer and Human Rights literary conference at Harbourfront, a book based on papers at that event and three commissioned posters by local artists before approaching me to program a film festival we eventually called Forbidden Films, which would deal with cinema and censorship worldwide. We decided we wanted to do an awareness builder, a fundraising event on March 8, 1984, and the person we wanted was Robert Frank, the Swiss-American photographer and filmmaker.

We found his phone number, because in those days you picked up the phone and called people, and Peter McCallum called. McCallum is like his terrific photos of art installations, cityscapes and industrial spaces; he has a dry voice and is taciturn and very, very precise. He’s an artist and a deep thinker but probably the last person you could imagine selling anyone on anything. Well, Peter got on the phone with Robert Frank and somehow convinced him that our project was a very good one. He really sold Frank on coming to Toronto! The second call was from me and our festival co-coordinator Gary Betcherman and Robert agreed to come for a weekend. We programmed one night at the Danforth Music Hall, which had 1200 seats, and we filled them all. It was the most successful single night I’ve ever been involved in producing. We showed Cocksucker Blues, Robert’s Rolling Stones-commissioned documentary about the band. I had arranged with Robert that we would program two nights of films. I told Robert that we’d do one big night for fundraising, but that he was a great artist and I knew another venue that would be perfect to show more personal work to the filmmaking community. That was the Funnel. So we filled the Funnel the next night on March 9. We showed some of his more experimental work, including Pull My Daisy and Me and My Brother.

I got to know Robert pretty well; we really hit it off, especially when he came to Pages. He loved books—I remember he was reading Thomas Bernhard at the time -and thought the bookstore was excellent. We hung out in the back room at Pages one evening and had drinks. He was in Toronto for three days and we went out every night. I noticed that when he talked to me his eyes would move in all these different directions. I finally asked him about it and he said, “It’s just a reflex I’ve had all my life. I’m kind of taking photographs.” It wasn’t like he was bored, he could hear what I was saying, but at the same time his eyes were composing shots. I asked him about Peter McCallum, “why did you listen to him?” Frank said, “He sounded so unhappy on the phone, I didn’t want to tell him no.”

Mike: Why was Cocksucker Blues a forbidden film? And what did Robert Frank think of the Rolling Stones?

Marc: Robert had a young friend named Danny Seymour, who was his assistant at the time of the making of Cocksucker Blues. He was a mentor to this up-and-coming photographer. It turned out that Danny got addicted to heroin because he was hanging out with Keith Richards and eventually Danny disappeared and is assumed to have either been murdered or OD’d somewhere in Central America. That was one of the things that really soured him on the whole experience. The man’s had tragedy — his daughter died in a plane crash, his son was mentally challenged and eventually passed away in an institution — what didn’t go wrong? He said to me that he thought the Rolling Stones were completely overrated; he was interested in them at first but after a while he felt that they didn’t have any substance. I asked him about the Beats and he said, yeah, Ginsberg, Burroughs and Kerouac had things to say, they were searching for a new way to live, but the Rolling Stones were a bunch of middle class boys making music.

I think what the Rolling Stones hated most about the film wasn’t the famous blowjob or the people shooting up, because the debauchery wouldn’t have worried them. I think what troubled them was that he portrays them as ordinary people who are not that smart or interesting. That’s why the Stones had their lawyers stop the commercial release of the film. I think Mick Jagger realized that banning the movie was a bad idea, so they finally came up with a solution. Robert could show the movie four times a year, but Jagger brilliantly added a proviso that Frank had to be there and introduce the film. Of course Frank couldn’t stand doing that. Showing up for a hundred people at the Funnel was fine. But to stand up in front of a thousand Rolling Stones fans? The film has been barely seen on screen as a result of that decision.

Mike: From October 28-31, 1984 legendary filmmaker and performance artist Jack Smith did a five-night stand at the Funnel, which was announced as “Exotic Landlordism of Crab Lagooon-In” though it quickly morphed into “Brassieres of Uranus.”

Marc: That was during Forbidden Films, which ran in venues from the Bloor to OISE to the AGO’s Jackman Hall to the Rivoli and the Funnel, in late October. We contacted Jack in New York through Ross McLaren but he showed up without his film Flaming Creatures, which was what we wanted to screen. I guess he was worried about the border, but being Jack he didn’t tell us. We had him stay with Martin Heath. He was spectacularly unhealthy at the time. He kept saying he had the flu, he couldn’t get to sleep, he was up all night every night. On the last night of five nights of performance, he had Funnel director David McIntosh standing on a ladder wearing a bejewelled anal brassiere and then berated him.

Every night we would go back to Martin’s place which was in the old Chinese noodle factory and Martin would show movies and Jack would make these theatrical groans about how sick he was and make offhand remarks about people that he hated. Martin had a roommate named Remo, a tall willowy gay kid from Austria. Remo was very interested in Jack; he helped him out with the Funnel shows and was kind of awestruck by him. I was so dumb in those days I kept trying to get Jack to talk about the New York art scene in the Sixties and of course that was the last thing he wanted to do, so he kept putting me off. I tried to get him to talk about Manny Farber, and he didn’t hate Manny Farber but he hated everyone else. Who was it he hated the most? Jonas Mekas. He called him Uncle Fishhook.

I felt that Jack was very impressive and interesting and it was fun to hang out with him, but we didn’t really connect. With some people, like Robert Frank, my trump card was having Pages, but Jack didn’t care about that. To him, I felt establishment. Do you know what I mean? He barely tolerated me, unlike David McIntosh who was vulnerable to him. But I was involved running this crazy festival and I knew the people who would love him so I didn’t have to sorry about it.

Mike: You did your own performance at the Funnel.

Marc: Shortly after opening Pages I hired Christian to work at the store. On Sundays we’d open up and put the various sections of the New York Times together. People would drift in and we’d have a really great morning. It felt magical. At some point in the afternoon we would go off to his place; I hired Thomas Ziorjen, a graphic artist, to do the afternoon shift. Christian had a studio with Ed Lam and Ian and Rachel Lowe, who has become a documentary and TV producer. They lived right on the corner of Duncan and King, above what turned into Crocodile Rock. It was supposed to be their office but of course they were living there illegally. We’d talk about the Funnel a lot and books.

A few years later, Christian and I were out drinking with Peter Chapman. Christian could do a devastating impression of William Burroughs, and Cities of the Red Night had come out fairly recently. I was reading a book called Six Guns and Society that offered semiotic takes on the western. Peter suddenly said that we should do a performance piece for the Funnel’s opening night in, I think, 1983. It would involve Westerns and William Burroughs.

I knew the Neoist performance artist Gordon W and his friend Istvan Kantor aka Monty Cantsin, through Martin Heath. Gordon was notorious for a number of things, most controversially his attack on Margaret Dragu. In retrospect I can’t believe I was still friendly with him after that, but I guess I was. Gordon told me that he just thought he was contributing to Dragu’s performance piece but in retrospect it’s clear that he was trying to humiliate her. He had a chapatti stand opposite the Black Bull in front of a parking lot where they still sell hotdogs. I was going over to Martin’s every Sunday night after showing films at the Rivoli. We’d go back to his place with some of our friends and sit around until four or five or six in the morning. Martin had an incredible collection of films; we would watch amazing Eastern European animation, and shorts by Roman Polanski and Pierre Etaix’s Yo Yo and Alain Resnais’s great documentary about the Bibliotheque Nationale.

Mainly because of those crazy Sunday nights, I stopped being the person opening Pages on Mondays. You can’t work seven days a week forever, which is what I did at Pages from 1979 throughout most of the Eighties. Pretty quickly, I started stealing bits of my time back from Pages. Film became a way of having a more personal or artistic time. It wasn’t that I didn’t feel that Pages wasn’t an artistic project too, but I was there every day, so whenever I could get away, even to work elsewhere, it felt like play.

When Peter Chapman suggested to Christian and me that we create a performance piece for the Funnel, we decided to get Gordon involved. After all, he’d done lots of performance art. Christian, Peter, Gordon and I got together and had a great time figuring out what we’d do. Gordon would dress as an Indian—which he mostly did anyway—and lay down eastern rhythms on a tabla, Christian would “be” William Burroughs reading from a Wild West section from Cities of the Red Night, and I would lecture from the semiotics book wearing a lab coat. Peter found a silent western and ran it backwards.

We called the piece Cowboys, Indians and Burroughs. I thought the performance was going well when all of a sudden Gordon decided that he was going to light his (bread) hat on fire. Some people told me later that I endeared myself to the Funnel forever because I started screaming, “You’re going to burn down one of the few places in the city that we love,” as I tried to stamp out the fire. For Gordon it was all part of the performance, he kept playing his tabla as the semiotic lab technician stamped out the flames and the film rolled behind us. That was my performance debut at the Funnel.

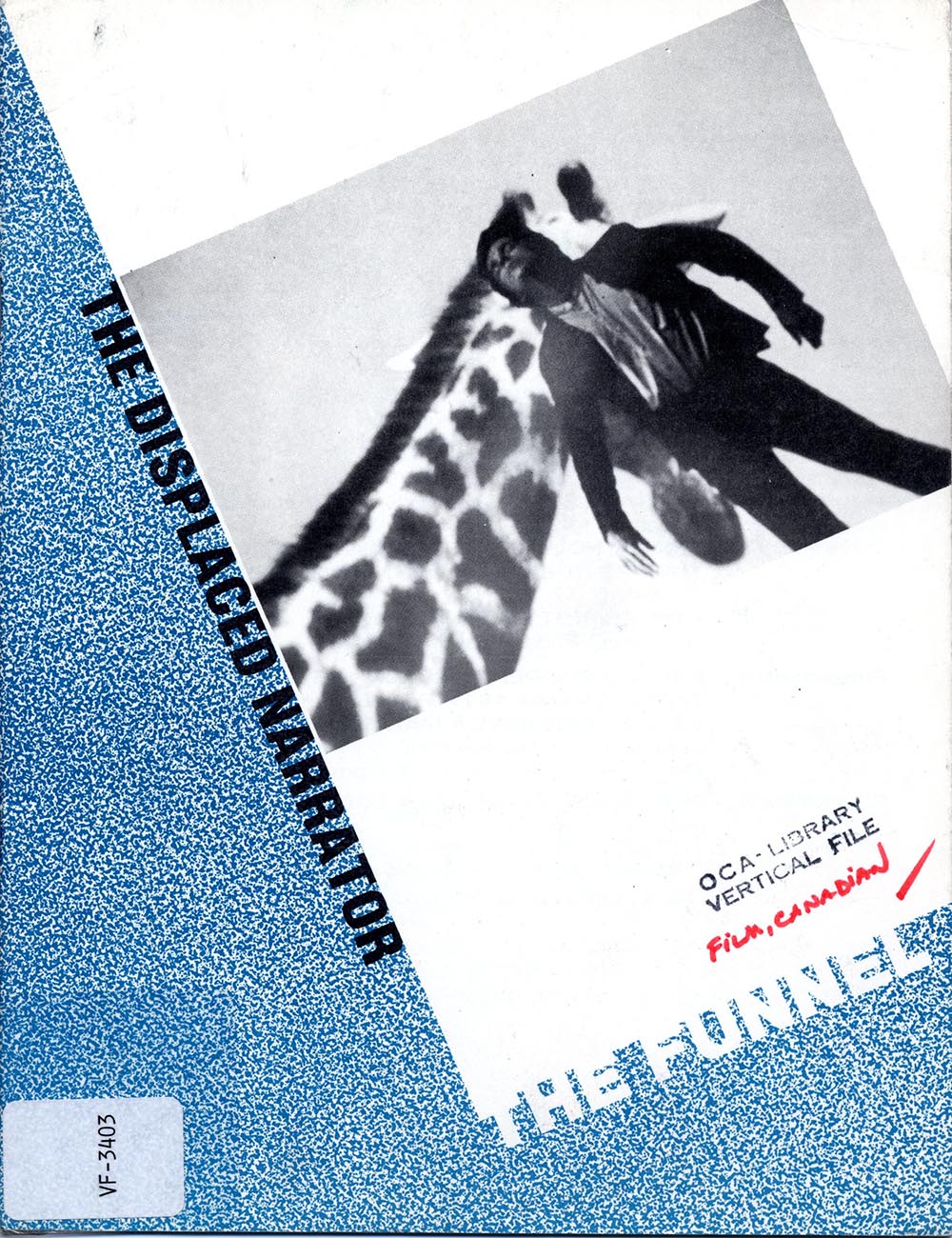

Mike: In February and March of 1984 you co-curated a six-night series with Carol McBride called The Displaced Narrator. It kicked off at the Art Gallery of Ontario with Chris Marker’s feature-length memory essay Sans Soleil, then shifted to the Funnel for four nights in March.

Marc: Carol McBride was a great pal. Carol was part of OFAVAS, the key anti-censorship organization in Toronto and I was programming Forbidden Films when we met. I must admit, I liked to go out on Queen Street and have dinner and just keep on drinking and talking until closing time. So did Carol. At the time, Carol was David Cronenberg’s assistant; he had just made Videodrome, was working on The Fly, and thinking a lot about Burroughs’ Naked Lunch. Carol was fascinated by the idea of displaced narration. She was developing Wetworks, a big, gorgeous, experimental film that used voice-over, which eventually premiered at the Festival of Festivals (now TIFF) in 1988. She had Adam Swica shoot it in 35mm at a time when no one was making avant-garde film on that scale. It looked amazing even if, ironically, it had some narrative problems.

Mike: What is displaced narration?

Marc: While cutting a film you work with a set of images that can be put together in a variety of different ways. What would the images look like if you put on a different soundtrack or used a different narrative voice? As much as film is primarily a visual art, it’s also one that is greatly transformed by voice, sounds, music. Russian montage experiments began with an impassive face as a reaction shot to a series of views. The same expressionless face appears benevolent looking at a grandmother, or as a leering voyeur looking at a naked woman. Could a similar kind of experiment be done using sound?

Our program The Displaced Narrator asked: how do you position a narration, is it first person or third, and can you shift from one to another? What happens when you use a narration which has no body attached to it, when the body becomes your imagination because it’s “displaced.” In other words, the words you hear don’t arrive out of the mouth of an actor, or anyone appearing onscreen. The best example of a displaced narrative voice is in Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil. I still argue that it’s the best documentary of all time, though others would argue it’s not a documentary at all. What can be more delicious than that?

In Sans Soleil, Marker shows us snapshots-or doc scenes–from his life but he wants to disguise that via the narrative voice of a woman who has been receiving letters from a cinematographer named Sandor Krasna, (one of Chris Marker’s many pseudonyms.) Throughout the film, we see images that are real, mostly shot in Japan and Guinea-Bissau. To explain these pictures we are offered words that have arrived via letters. The epistolary form is one of the earliest devices used in the novel, going back to the 18th century. Marker uses that structure in the film, which is unusual, particularly in a documentary.

While the images of the film are “real,” they are now being reconstructed by a voice that is also questioning its own abilities of reconstruction. Marker does this by having the woman who is the recipient of the letters read them aloud; she wasn’t there and has no way of verifying the accuracy of anything written to her. This frees the text and allows it to be open to a myriad of interpretations. In this way, Marker’s film mirrors what Pollack achieved in abstract painting and Feldman in music. It offers possibilities of endless engagement and interpretation: there’s not a single way to experience the work.

Carol and I were absolutely entranced by Sans Soleil. It was our signature piece for The Displaced Narrator; the rest of the program flowed from it. We threw in many other examples, like the Anthony Balch/William Burroughs pieces which used Burroughs’s cut-up techniques to re-imagine voice recordings and apparently random visuals. We were interested in the early works of Chris Marker’s colleague Alain Resnais, who had worked with “nouveau roman” writers, so we included Marguerite Duras and Alain Robbe- Grillet, both of whom became directors. Then we wanted to show off local talents, including Midi Onodera and Peter Dudar. They were fine but our Canadian examples weren’t truly up to the sophisticated standards of Marker, Duras and Resnais. I hope that’s OK to say after twenty-five years.

We were also wrestling with the question: what is avant-garde and what is documentary, what are the points of intersection? This question came up again with the program I did with William Beattie. He was our back up projectionist (at the Rivoli), who we employed when Martin Heath and Hans Burgschmidt weren’t available. William was much more interested in doing curation than projection in any case. William and I came up with a program called Transmutations: Formal Inventions in Documentary, which looked at how documentary fits into avant-garde cinema. We showed two nights of the program at the Funnel on March 6 and 13, 1987 and also curated two nights at the Rivoli, one at OCA and one at Jackman Hall. We ran a night of Beats and Beat-inspired movies, and a film that William was obsessed with called The Ax Fight about a constructed battle between two native tribes in South America. William and I loved part four, the re-edited footage.

I wish I had a program in front of me so I’m relying on memory for this but I’m sure we showed films by Richard Kerr and Phil Hoffman. I have a feeling that we showed part one of Hour of the Furnaces. Martin Heath had a couple of prints of early Rouch; we showed Les maîtres fous and, I believe, Jaguar. Martin had Polish and Czech shorts which got slotted in for flavour. My memory is that the Funnel screenings weren’t all that successful. The ideas were too complex and intellectual. No one “got it” but us and maybe Martin. I don’t blame the Funnel’s lack of outreach at all for the program’s failure to attract an audience — just us. I wouldn’t say “no one came,” but we were getting twenty or thirty people, which given the number of people we knew in the scene at the time was pitiful.

Mike: In the summer of 1987 the Funnel moved from its King Street location to Soho Street, just a block and a half away from your bookstore Pages. After years of east side exile, they had moved smack downtown where the two of you were practically neighbours.

Marc: Apart from the two nights William and I did with Transmutations, I hadn’t been around as much at the Funnel after 1985, not that I had a falling out or anything. If someone had asked me to become a member of the board I would have thought about it; instead I got really involved with the Images Festival, which I helped to start in 1987 and ‘88. The time and energy I had for avant-garde cinema was put into the festival.

I thought the move was a good idea, but keep in mind I didn’t know the Funnel was going bankrupt. I thought incorrectly that because the Funnel was getting annual funding from the feds and the province there must have been money.

Mike: Do you remember talking to (Funnel director) Gary McLaren?

Marc: Yes, but I found him a difficult person to talk to. I have it in my head that he was a taciturn guy that didn’t say very much. Is that true?

Mike: Yes.

Marc: It is true, ok good, it wasn’t just me. You know what I was like in those days, Mike, I was probably overly effusive. I told him that I was looking forward to being neighbours and that I would be happy to help in any way and he just stood and looked at me. At least that’s how I remember it, though I guess he was polite but non-committal. But whatever, I assumed that people from the Funnel would come knockin’ on the door and I wouldn’t be turning them away. I’m surprised I wasn’t asked to help at all. I don’t think I was ever physically in the building; I was never invited and never went to a screening.

My partner Judy Wolfe has been professionally involved with many arts organizations as a consultant. She’s discovered a recurrent pattern in artist-run centres . They often start with a charismatic leader. For however long, it could be a year or thirty years, the leader gets things rolling. Through charm and drive such people gather the necessary energy and people. At some point that relationship sours: the mission, the mandate, the organization itself begins to change, only the charismatic figure can’t see it. He or she is blind to changes, much like many parents are to their kids. S/he doesn’t see that the child is now an adult, that it’s time to pull back and let them make their own choices. This happens everywhere, at art galleries, film festivals, organizations small and large.

So I feel sympathetic towards the McLarens and the other people who started the Funnel in the Seventies. Starting something is major, but at some point you should leave. It’s almost in the DNA that someone with so much oomph finds it hard to say: oh, you mean I shouldn’t be around anymore? I let go of the Images Festival; I could have been a lot more difficult about all that, but I wasn’t crazy. It seems to me that the original group had run out of energy but wouldn’t let new people come in to breath new life into the Funnel.

Mike: I think that’s why Pleasure Dome endured. None of us wanted to build an empire. We designed a porous structure that allowed many people to become part of it, and then we left. We assumed new people would take it in unforeseen directions. That’s how organizations can stay relevant and alive, by having experienced hands step down to allow young people their own dreams.

Marc: When I heard that the Funnel had ceased operations, I remember thinking what a shame it was over and how bizarre that they never approached me. I don’t think I was particularly angry, but it was ridiculous, I could really have been helpful—and I’m sure many others could have injected the Funnel with new energy. For the Funnel to close in a period when people were becoming more interested in experimental work than ever before meant they really refused to change and open up their operations to newer, younger people with fresh ideas. That’s what’s kept Pleasure Dome and the Images Festival alive for decades. I’ll always miss the Funnel and I do remember with fondness the great nights I spent there.