Godard On TV

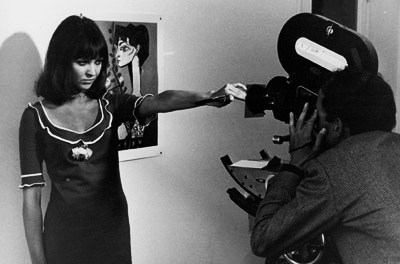

He is notoriously difficult, bristling with hostility, an unmanageable guest. Once a filmmaker’s filmmaker, much of his work since the mid-seventies has been made for television, and he has appeared alongside it, in all of his acerbic glory. Questioning those who would ask him questions. Bitterly dismissing the network faces trying to massage him into the flow. “When you go to the cinema you look up, when you watch television you look down.” This is Jean Luc Godard, accepting a César award on TV, his innumerable encounters with the medium (it’s neither rare nor well done—hence a medium) captured in the hilarious anti-documentary Godard À La Télé (53 minutes 1999) by Michel Royer. Comprised of clips gathered from the past fourty years, we watch him turn from the playful ham directing Bardot in the sixties, to the bitter Platonic dialogues of France/tour/détour/deux/enfants.

Godard: Didn’t you see shows that made you say it’s shit?

Boy: Yes.

Godard: And where does shit come from?

Television as the asshole. The portal of excremental culture. As Godard stares into the butt of corporate culture, he strives always to make an intervention. He adjusts the camera angles of his interviewers, he calls attention, relentlessly, to the techniques of shaping that television is applying, at the moment it is being applied. He has news anchors confess their ignorance, asks talk show guests to close their eyes in order to explore the relation between image and sound, pronounces his interviewers liars, and the programs themselves empty vehicles of self promoting noise. And yet, as this self reflexive clip collage is quick to make clear, this all makes for good television. These moments of dissent, filled with a palpable tension, often conclude with Godard’s abrupt departure from the show. There is genuine hostility here, hence drama, and a sense of the unexpected. The quips never stop and always, of course, he maintains the allure of stardom. Later, a commentator charges that this is nothing but a shtick. An act. Why? Because no one could be that good on television without preparation. Why? Because attacking television makes for great television. There is no outside.

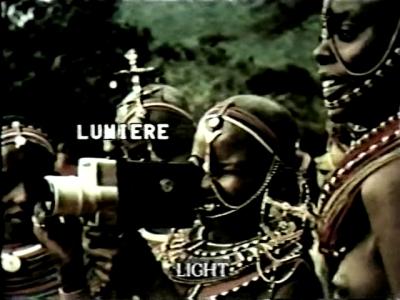

As filmmakers we’re used to working with pictures, working on the image. But most of us arrive at our pictures like office proles punching the clock. We produce pictures, but there is no real work in them, no labour inside the frame, or between them, so when they hit the screen there’s nothing really, a shadow on a wall, a joyride forgotten as soon as it’s over. These are not pictures that produce meaning, but occlude it, like the images we watch every night on the news, which serve as captions, illustrations of the text. These pictures are used to disguise situations, to absorb them into a flow of momentary spectacle and inflation, and then erasure. How many of us can remember a news broadcast from eight years ago? Eight days ago? Last night? There is no memory, and hence no time, in these pictures, because they aren’t working, and the news announcers know this too, which is why they always speak with their backs turned to the image. They know there is nothing there. They know that what we are being offered in place of pictures is a blind. It is a very simple thing to make pictures now, but it has never been more difficult to make pictures that work. Working pictures.

If you could see more on TV, rather than hear. If you spoke less, I’d remember more. But as you only speak, I see nothing…. We are afraid of images. We all are… But we don’t want to see. TV won’t see. It just shows. Jean Luc Godard

This difference, between seeing and showing, between pictures which show themselves, and pictures which claim to be transparent, a window on our world, “showing Canada to Canadians” or the world to itself, is clearly marked in our post millennial embrace of the digital. Take for example, the exploding Hot Docs festival, which has become a showcase for the documentary form, now also a window on television, as this genre is increasingly strained through the dictums, formats and mandates, of broadcast. What a fabulous variety of subjects. An unprecedented number of makers. And already in evidence, everywhere at the festival, are the digital technologies which are about to realize the utopian dream of the sixties, that everyone will be able to own the means of their own reproduction. In this infinity of pictures, how is it possible to claim, a la Godard, that we are afraid of images?

There was a time, a heartbeat away in the evolutionary scheme, when one had to travel to see a picture. I am trying to imagine it, stand in their place, before an image, the only image I’m likely to encounter in a week or a month. And find that I can’t. I’ve been too well trained, not to see, but to ignore. If I saw every image that was around me, I would never get to work. Is this why images, even hundreds of years back, when the only pictures were in churches or mosques, or scrawled into cave walls before the hunt, were not part of our working world? Except of course for those who produced them, who worked in the dream factory, or the factories of church and state. For their consumers, images were part of the world which waited for work to finish, on days of rest. Nights of escape. How far would we have to travel today to escape pictures? Though most remain invisible and beyond recall. They have been rendered invisible not from withholding, but by their fantastic profusion. They are everywhere and nowhere. Like television.

Is it true, as Godard claims, that the more television tells us the less it shows? And what of the documentary?

The documentary has grown in importance in the past decade, becoming part of the invisibly visible empire of pictures, the programming of time that is television. It is not just the documentary, but specifically the legacy of cinema verité that has been recouped in order to fill the many new hours available in a multi-channel microverse. Cops prowl the streets with camcorders on the dash. Surgeries are performed in the operating theatre while relatives weep in emergency. Talk shows feature guests telling stories too awful to be anything but true. Here is the truth, thirty times per second. Just what are these pictures showing us? Or is it the other way around? Are we presenting ourselves to television? Aspiring to its condition of uninterrupted flow, of instant communication and disposable bon mots? Of a ceaseless confessional biography. Are we part of a global social experiment? Was McLuhan wrong? Is it possible to embrace the medium without its message? What is the message of television?

This is television. It’s not made to communicate but to pass on orders.

Originally published in: POV Magazine, Summer 2000

Jean Luc’s Tears

I never get an erection in a Godard movie. This bothered me as the years went by, film after film (this one, maybe this one?) mostly because Godard was always my fave director, and there seemed to be something missing. Was this only head and shoulders kino (leaving the knees, the orbits of the waist, the closed eye of the anus, for others)?

Others have made me cry, lesser Gods in the heaven of cinema, hacks even. One afternoon, for instance, in a heavily medicated state, even the execrable sequel to the sequel of The Matrix brought tears. When Keanu Reeves’s confessions of love stir the heart, it’s time for a transplant. But the largest tear fest of the past decade occurred during Dancer in the Dark, where we watch Bjork being emotionally flogged for three hours by that genius Danish dog (Why are the cruelties of some so compulsively watchable, while others are only horrifying?). A woman, well okay, a girl really, a girl-woman, not yet twenty, began to sob from the seat behind me, starting up half an hour into the flick, and continuing for the rest of the movie. Before Bjork could die this poor girl collapsed, doubtless from dehydration. I was crying too, in fact, everyone around her was sobbing. She was the cheerleader of tragedy, giving us permission, leading by example.

When I was her age I sat my first Godard flick, Masculin, Féminin. I got pretty high before I saw it so it’s a wonder I still have two enduring memories. Though the first is only confusion, I didn’t have a clue what was happening, couldn’t find a plot to follow (Do we have to wait for the clothes to dry before leaving the damned laundromat?). Secondly, there was something underneath my finger nails about it, dirty even. In other words, it wasn’t removed, not all slick and Mary Poppins-like, and that bothered me some, I wanted to reach for my umbrella and lift away from it all, but that wasn’t going to happen here. Though as the drugs wore off I started catching glimpses, corners of the room he was trying to show me, and I found myself happy, even in my confusion, to be looking up to him. Of course in the movies one is always looking up. But I didn’t really have a good cry in a Godard film until Two or Three Things I Know About Her. The first tear fell after the camera finds the universe in a coffee cup, the milk swirling like some far off galaxy, and for the narrator, heard in voice-over, her body and hope and desire is also far away. “Given the fact that each event changes my day to day existence and given the fact that I invariably fail to communicate, I mean to understand, to love, to be loved, and as each failure makes me feel my loneliness more keenly…” Several years later my best friend spilled this all out, word for word, in a donut shop we liked to meet in, and I cried to hear her tell it, and then she looked up and smiled. She was quoting and I hadn’t noticed a note. Quoting Godard.

Later in the movie the heroine trembles, it’s Juliette, who has replaced Anna Karina as the star and object of Godard’s affections. Somehow this is part of the drama as well, this personal revolution which will precede the events of spring 1968, only a year away from this movie’s released. Juliette works for extra money as a prostitute, and after a series of alienated encounters returns to her husband who works in a garage. The voice-over uses this meeting to reflect on, well, everything really. Godard is so bruised, so cracked open, his falling in love allows him to find the world everywhere he looks. The quote goes like this:

“I’m only looking for reasons to be happy… and if I now try to analyze it further, I discover that memory is our chief reason for living, if we have one, and secondly the present and the capacity to live in the present and to enjoy it, finding a reason to live, however fleeting, and enjoying the space of a few seconds, just as one found it, in its own unique set of circumstances… My aim… is a new world where humans and things would interrelate harmoniously. It’s really more of a political issue than a poetic one. In any case, it accounts for this passion for self expression. Whose? Mine. Writer and painter. It is 16 hours, 45. Should I have described Juliette or the leaves? It was really impossible anyways to describe both… so let us just say that the leaves and Juliette fluttered gently in that late October afternoon.”

After this movie he would make La Chinoise, then plunge into the savagery of Weekend. He would never be so unguarded, so tender, again.

The War of Pictures

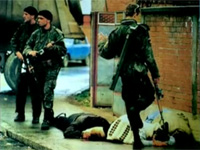

Here is a two minute movie by Godard called Je Vous Salue, Sarajevo. It consists of a single photograph, shattered into fragments, which the Swiss-French maestro summons in a gathering dread. How can he make this picture visible? How can he show this moment, return us to this moment, rescue it from the too many others which bury its difficulty, its outrage and injustice? Godard hurls it against his plasma screen and breaks it into bits, and then offers it up to us piece by piece. Each frame is a kind of footfall for the eye, this operation might be named: how to make an approach. The unbearable war, the unspeakable act, the impossible gesture. One step at a time.

A friend told me last night that she once marched with the others against the bathhouse raids, worked at the woman’s shelter, warmed herself with the necessary certainties of the young as she kicked against the machine, shook her fist against the big picture. She’s a mother now, and has offered more recently to look after a friend’s daughter once a week. It is not the march on the capital, it is not tearing the system down one brick at a time, but still she is standing on the front line of her life. And while she used to embrace the war, the us and themness of the struggle, today she works for peace. No, her babysitting efforts will not feed another child from Gaza, but even so, she is opening her arms to the here and now of her neighborhood. She is working for peace with her partner, her own children, and the children who have come to take the place of the life she used to have. The adventure of peace has begun again at home, where no one will notice except the lives she is busy changing with every breath, one kindness at a time.

Here is how Mary Gaitskill puts it, running the same lines through her Veronica hair as if they belong there. I am in the midst of her language thickets now, wishing I could understand how she manages to lay it down so cleanly.

“The place Joanne is building inside has rooms for all of this… In these rooms, each thing that looks crazy or stupid will be like a drawing you give your mother, regarded with complete acceptance and put on the wall. Not because it is good but because it is trying to understand something. In these rooms, there will be understanding. In these rooms, each madness and stupidity will be unfolded from its knot and smoothed with loving hands until the true thing inside it lies revealed.”

The voice-over text of Je Vous Salue, Sarajevo, cribbed and rehatched and breathed out of the old man’s mouth, goes like this:

In a sense, fear is the daughter of God, redeemed on Good Friday night. She’s not beautiful, mocked, cursed and disowned by all. But don’t get it wrong: she watches over all mortal agony, she intercedes for mankind.

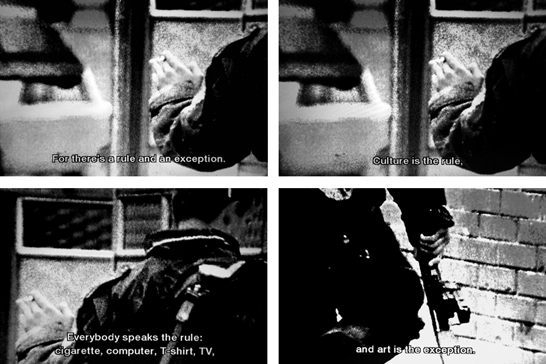

For there’s a rule and an exception.

Culture is the rule, and art is the exception.

Everybody speaks the rule: cigarette, computer, t-shirt, television, tourism, war.

Nobody speaks the exception. It isn’t spoken, it’s written: Flaubert, Dostoyevsky. It’s composed: Gershwin, Mozart. It’s painted: Cezanne, Vermeer. It’s filmed: Antonioni, Vigo.

Or it’s lived, and then it’s the art of living: Srebenica, Mostar, Sarajevo.

The rule is to want the death of the exception. So the rule for Cultural Europe is to organize the death of the art of living, which still flourishes.

When it’s time to close the book, I’ll have no regrets.

I’ve seen so many people live so badly, and so many die so well.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bJcqk3PcOlg&feature=related