Originally published in the Globe and Mail, July 2, 1983

“When it comes to sexuality, to taking the clothes off, the courage just isn’t there.”

“It was in 1969 – I can remember it as if it were yesterday,” says Bruce Elder, recalling the first time he saw Michael Snow’s film Wavelength. The movie consists of a slow, 45-minute forward zoom in a barren room. “It was an incredible experience. After about fifteen minutes people started booing and walking out. They truly thought this was the most boring film of all time. My wife was with me, and I urged her to hang in, that I suspected that this was one of the most important films ever made.”

Elder, who is himself one of Canada’s most distinguished experimental filmmakers, looks back to the sixties and early seventies – the era of Stan Brakhage, Andy Warhol, Kenneth Anger and Snow – as the golden age of avant-garde cinema, when filmmakers and the esthetic principles they advanced attracted loyal adherents as well as vigorous opponents.

There was always controversy. When Warhol pointed a lens at the Empire State Building, or at someone sleeping, and left the camera running for hours, people were outraged, but it was talked about and being an avant-garde filmmaker meant being a part of a dialogue that was constantly giving birth to new artistic ideas.

Elder, who teaches cinema studies at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, is more cautious in his praise of the experimental films made by young artists today. “Oh, I’m sure young filmmakers look at my work as ‘daddy cinema,’” he says, “But you know, I don’t see the same kind of rigor among young experimental filmmakers today as there was a decade or so ago. The work being made is evidence of crisis in experimental cinema, one that comes around every twenty years. There is a lack of a dominant esthetic, a lack of consensus about what kinds of issues are most pressing and should be dealt with. Today there are no major figures in avant-garde cinema.”

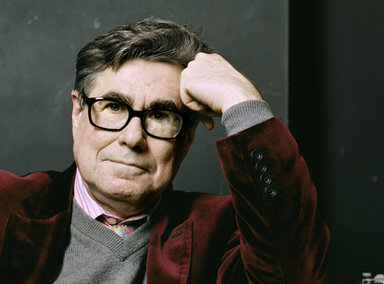

Elder, a fidgety man with a flip of hair over one side of his forehead that makes him a Warhol lookalike, is working on a book about Canadian avant-garde cinema. As one pale hand strenuously pulls his features into freakish contortions, he looks for the right word to describe the film work of Canada’s younger artists.

“It’s what you might call Baudelarian cinema,” he says, referring to the nineteenth-century French symbolist poet. “There is an interest in achieving a certain roughness, which is why many young filmmakers are working in super 8. There’s also a connection to the punk culture but, although that implies rebelliousness, I find that when it comes to really making a strong statement, when it comes to sexuality, to taking the clothes off, the courage just isn’t there.”

“I don’t know what Baudelarian cinema means,” says Anna Gronau. who at thirty-one is one of the older members of the new crop of avant-garde filmmakers in Toronto. “I’m not interested in displaying myself sexually. There are other kinds of courage than exhibiting one’s body. If sexual boldness is a yardstick for creativity, that’s just silly.”

*

Although young experimental filmmakers have yet to turn avant-garde on its head, they are just as active as their predecessors, countering mainstream cinema with a “radical otherness,” the term used by P. Adam Sitney, author of Visionary Film, to describe the mandate of avant-garde cinema.

The mecca of that activity during the past five years has been a small warehouse in Toronto called The Funnel, a theatre run by a core of about thirty filmmakers who pay $120 membership dues annual and organize regular screenings of experimental films (associate members pay $30 annually). Recently it has expanded into a multi-media venue, combining film with theatre, dance, readings, visual art installations and, lately, litigation. After several disputes with the Ontario Board of Censors, The Funnel, armed with the new Canadian Constitution’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms – has been fighting the Censor Board in the highest courts of the land.

“The Funnel began with only one thing in mind: the exhibition of experimental films,” says Funnel programming director Michaelle McLean. “We were drawn into other issues. We had been screening films as part of our regular programs, and then one day the Censor Board just stumbled upon us and informed us that, from then on, we’d have to submit all films to them for prior approval. We tried to explain that we are not a part of the commercial entertainment industry, but they didn’t listen.”

Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society: David Poole, Anna Gronau, Cyndra MacDowell, photo by John Porter

McLean is busy planning a series of benefits this summer to raise money to pay for the escalating legal costs of the Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society (OFAVAS) – an incorporated group headed by Gronau, associate Funnel member David Poole, and Cyndra MacDowell of the Canadian Artists Representation (Ontario) – which is challenging the Censor Board in the courts.

The February visit of Ondine, one of the brightest stars in Andy Warhol’s troupe during the sixties, was perhaps the biggest coup of the season. The Funnel charged $10 for tickets to see Ondine, who came to Toronto with prints of the Warhol films in which he starred – Chelsea Girls, Loves of Ondine, and Vinyl – tucked under his arm. The visit was of particular interest, since Warhol has pulled all his films from circulation and Ondine reportedly has the only prints available.

The dim, dilapidated, three-story warehouse at 507 King St. E., in the shadow of a Don Valley Parkway exit ramp, looks more like a garment district sweatshop than an avant-garde film venue. Indeed, one of the most notable things about The Funnel is its location, on the other side of Yonge Street, away from the artsy area west of Yonge along Queen and King Streets. The only hint to the passerby that inside there might be something beyond the ordinary are the words “The Funnel” scrawled in punk-style lettering to one side of the uninviting front door, a few yards from the clatter of streetcars.

Immediately inside the doorway, a variety of rusty, askew mailboxes and hand-painted signs indicates that a printing shop and a clothes designer can be found on this or that floor. There is no sign for The Funnel. It can be found by walking up one flight of stairs and following noodles of paint splashed haphazardly along the walls and on the buckled floorboards of a narrow hallway. It is uncertain whether this is a Jackson Pollock touch or just part of the general messiness of the building.

At the end of the hallway, another door leads to The Funnel’s gallery. On this day, the installation is a New Mexico desert scene, called Gallop Exit To, by local artist and filmmaker Rebecca Baird. Indian arrows randomly pierce the fluorescent yellow walls, on which an enormous snakeskin – ten feet long and a foot wide – hangs. Below are several cacti and a floor of desert dust. The room is hot – too hot. But McLean says, no, this is not real New Mexico heat, only the pipes, which are sizzling uncontrollably. The cacti and dirt are made of Rice Krispies. “Wait,” she says, disappearing into her office. She turns on the stereo and puts on a record by The Ventures called Apache, a tinny guitar song from the sixties. The multi-media effect is complete: a clippety–clop Rio Grande sound adds to the visual installation.

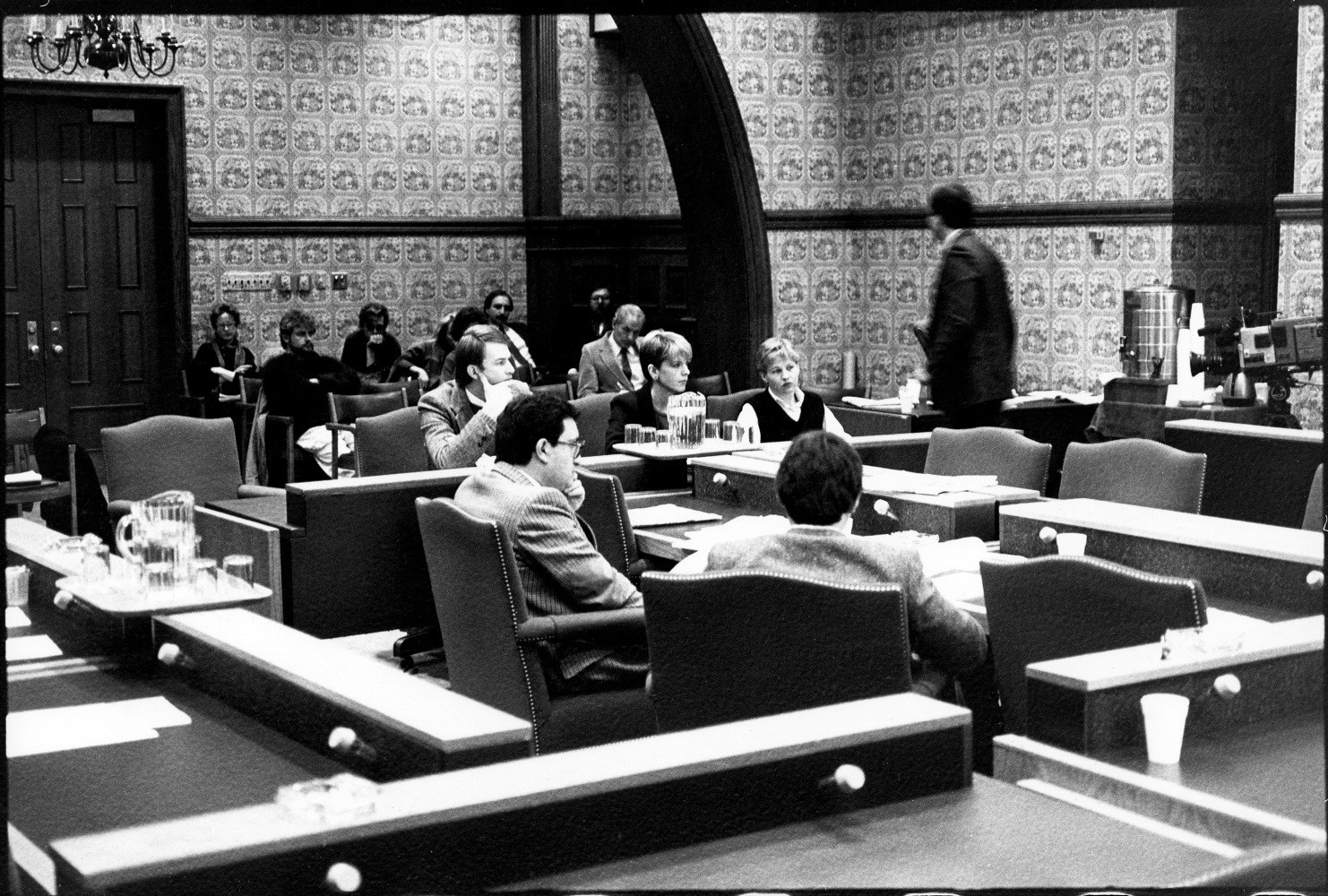

The screening room itself, in contrast to the rest of the building, is clean and cozy. The 99 theatre seats, donated by the old Imperial Theatre on Yonge Street before it became the Imperial Six, are worn but comfy. The projector room is also a small film production studio and library, where about 160 super 8 and 16mm films are filed alphabetically by the artist’s name.

Only a year ago, the organization was in disarray. That’s when the City Building Department slapped a $35,000 work order on The Funnel to bring the building up to fire safety regulations. The cost of the undertaking almost closed down the theatre, but through donations and volunteer labour, Funnel members completed the renovations in time to begin their season just a tad late.

The Funnel’s problems with government agencies go back even further, however – back to the riotous summer of 1977 and a brownstone building at 15 Duncan St., just behind Ed’s Warehouse. Now the sandblasted and respectable domain of Pope & Company stockbrokers, it used to be the home of the Crash ‘n’ Burn, one of the city’s most infamous punk clubs. Another tenant was the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC), which that summer was midwife to The Funnel’s birth in the basement of the building. The Funnel had no ideological affiliation with the radically left-wing CEAC, but it depended on the group for much of its meager $2,000 budget. The sword of Damocles had been hanging over government-funded CEAC for some time and when, in May 1978, CEAC published a photograph of the slain Italian prime minister, Aldo Moro, on the cover of its newspaper, complete with articles inside advocating “kneecapping,” the sword fell and CEAC died. Filmmaker Ross McLaren, who founded The Funnel and was the theatre’s program director at the time, says that when the Strike controversy was splashed on the front page of the Toronto Sun and was subsequently debated in the federal House of Commons, the Ontario Arts Council told CEAC that funding would no longer be available. The infant Funnel was homeless after one season. “That year was a very exciting time,” says Elder. “My students who had graduated kept coming back to me and telling me about all these great things that were happening down there on Duncan Street. The thing that impressed me most about The Funnel was how quickly it attracted so many top-flight filmmakers who wanted to come there and show their work.”

It was Elder, with his reputation as an academic and established filmmaker, who convinced government arts funding agencies to support the fledgling Funnel after the CEAC debacle. (The Funnel’s annual budget is now $100,000 – one third of which is self raised and two thirds of which comes from the Ontario Arts Council, Canada Council and Metro Toronto).

But after three seasons at its new home on King Street, more problems with the government arose. In the spring of 1981, The Funnel jointly sponsored, with the Art Gallery of Ontario, a retrospective of Michael Snow’s work, including his epic Rameau’s Nephew. The film was screened as scheduled at AGO, but afterwards, according to Funnel members, the Censor Board refused to allow The Funnel to screen the film unless the scenes which graphically showed sexual acts were cut. The Funnel and Snow united in their opposition to the cuts. (“I suppose they think that when your feet are submerged in expensive carpeting, your mind doesn’t get warped by nudity,” says Elder.)

Snow is reluctant to discuss the censorship problems regarding Rameau’s Nephew because, he says, it attracts a prurient interest in his work. “The Censor Board only draws attention to the ridiculousness of its activities.” Asked what scenes in the film the board found objectionable, Snow says with bewilderment: “I really don’t know. There were some shots of naked men and women. Maybe that offended them.”

Mary Brown, chairman of the Censor Board, is earnest in her defense of the board’s decisions. But when the censorship of “art” films is raised, it seems to hit a raw nerve. She says The Funnel and independent filmmakers have distorted the issue and manipulated the media to their own ends.

Under Mrs. Brown’s direction, the board has softened its former policy of requiring that all films be submitted to the board; now an exhibitor has only to submit a written synopsis of the film’s contents to get the board’s imprimatur. But the board still reserves the right to demand that any film contravening “community standards” be cut or banned. Recent additions to the board’s index are Elder’s The Art of World Wisdom (which won the 1981 Los Angeles Film Critics’ Award), and Al Razutis’ A Message From Our Sponsor. Elder’s film, an autobiography which contains scenes of the filmmaker masturbating, cannot be screened commercially without a permit being granted for each showing. Razutis’s film, which is about the exploitation of sex in the media, is banned and cannot be seen under any conditions.

“The Razutis film is the only film that has a censorship problem,” says Mrs. Brown. “We refused to license that film because it’s only nine minutes long, and it’s all hardcore footage – fellatio, vaginal penetration, you name it. That film would have had problems with the criminal code if we hadn’t banned it.” Without a license, A Message from our Sponsor cannot be screened commercially anywhere in the province; it can, however, be screened privately or in a classroom for academic purposes. Mrs. Brown says the Censor Board did not bar The Funnel from showing Rameau’s Nephew. She says The Funnel deliberately didn’t submit an application for a permit to screen it. “They waited until the issue had flared up in the media before coming to us and asking for a permit. And we gave it to them.”

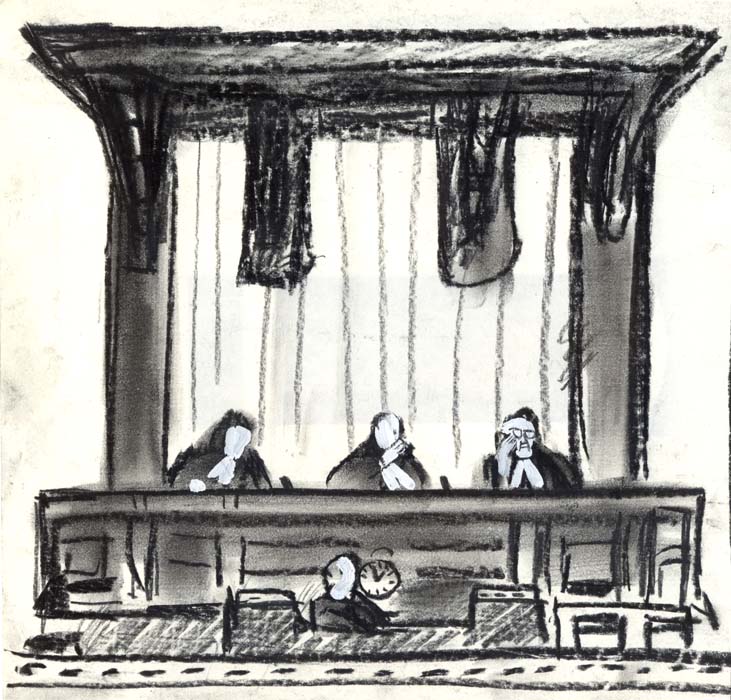

The suit by OFAVAS against the Censor Board is still before the courts. In February, an Ontario Supreme Court justice ruled that the activities of the Censor Board were in violation of the federal Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and that ruling which limits freedom of expression “cannot be left up to the whim of an official.” The provincial Government has appealed that decision, and government lawyers are now drafting amendments to the law regulating the activities of the Censor Board to extend its powers.

“What can be said, “ says Elder, “is that without a place like The Funnel, experimental films would only be seen in places like my classroom.” Says Snow, “I think it’s terrific what they’re doing down there. That The Funnel has survived this long is almost a miracle.”

Censorship is only one of the Funnel’s concerns by Michaelle McLean, 1983

Originally published as a letter in the Globe and Mail, July 16, 1983

We were pleased to see an article illustrated with the Funnel’s name and logo (Scenes from the Avant-Garde, July 2) in Fanfare, I would like, however, to correct a number of errors and omissions.

Freedom of expression is of critical importance, but in the context of the Funnel, it is only a part of our activities. During the seven years of existence, the Funnel has attempted to respond to matters that concern our community – whether esthetic, financial or legal. For example the Funnel was instrumental in the establishment of a separate jury for experimental film at the Ontario Arts Council. The Funnel assisted in the development of a network of centres across Canada which now includes film in their programming and promoted the introduction of a Canada Council program to assist them. We have formed a permanent collection of work for which we facilitiate distribution and promotion (a catalogue is due to be published soon).

The Funnel is unique in Canada and respected internationally. Despite what Fraser terms our “uninviting front door,” we are constantly complimented on the high quality of our exhibition facility and the enthusiasm of Toronto audiences by visiting artists from other regions of Canada, the United States, England, France, Germany and Japan. (While it would have been appreciated, the Imperial Cinema did not, as Fraser claims, donate the theatre seats to the Funnel – they were purchased from another artist-run centre.)

Through its continuing exhibition program, production facility, film collection, public workshops, newsletter, file resources and lobbying activities, the Funnel has established a structure that supports and encourages artists working in film and related art forms in Canada. The premieres during the past season of new work by Toronto artists include Anna Gronau, Adam Swica, David Bennell, Villem Teder, John Porter, Rebecca Baird, Midi Onodera, Fast Wurms and others, is evidence of a very active local community. It is because of, and for this community, that the Funnel has survived and grown. Despite the setbacks, legal and otherwise, their interest and energy ensures the Funnel’s existence.

The benefit series of screenings at the Funnel this summer is to assist in meeting the costs of the Funnel’s recent renovations – not to provide financial assistance to the Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society (OFAVAS) that is challenging in the courts the constitutionality of the Ontario Board of Censors. As an individual I have been involved with the ad-hoc committee Film and Video Against Censorship (FAVAC) for several years and FAVAC is currently involved in fundraising activities for OFAVAS.

During the month-long retrospective of Michael Snow’s films in the spring of 1981, co-operatively presented by the Funnel and the Art Gallery of Ontario, Rameau’s Nephew was scheduled to be screened at the Funnel, not at the AGO. When cuts were demanded, the Funnel, the film’s distributor (CFMDC) and the AGO launched an appeal to the Censor Board. The board responded that the film could be shown once, uncut at the AGO – in effect saying that they objected to the venue not the content. In support of the Funnel and the issue of freedom of expression Snow agreed to cancel the screening. The Funnel filed a suit against the Censor Board.

Shortly after the Funnel’s suit was filed, changes to the Censor Board’s appeal procedures were announced and the “form” (Examination by Documentation) procedure was introduced. The Funnel submitted an application under this procedure to screen Rameau’s Nephew and was granted permission. It was screened Sept. 4, 1983.

We appreciate the Globe and Mail’s continuing interest in the freedom of expression and the Funnel.

Michelle McLean

Director/Programmer

The Funnel

Toronto

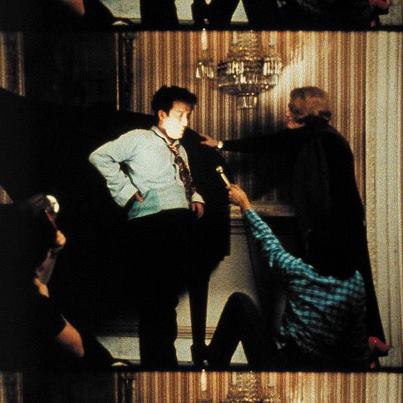

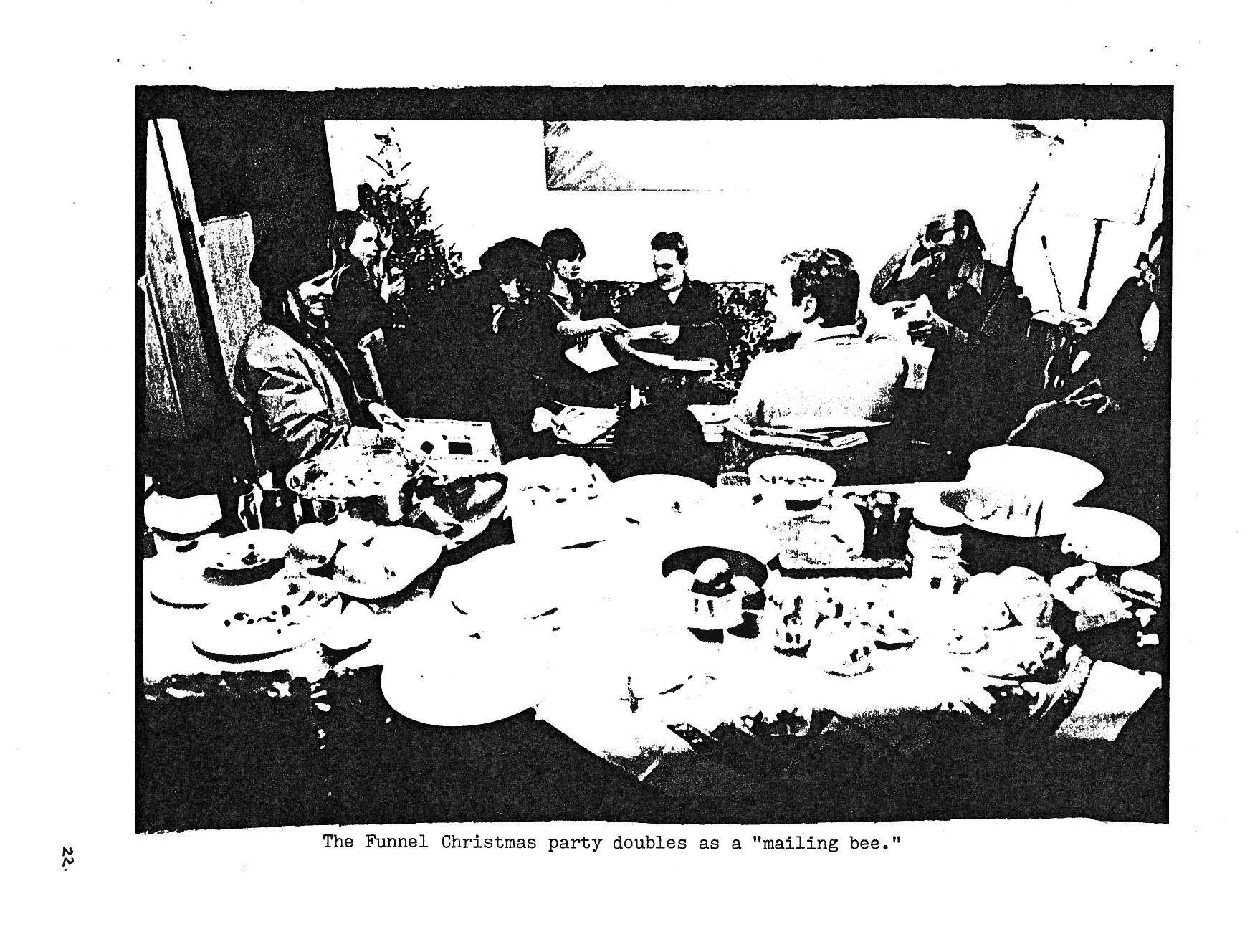

Funnel Christmas Party/mailing, December 1981. Anna Gronau, Amber Samson, Jim Anderson, (on couch: Mikki Fontana, David Bennell), Peter Chapman, Villem Teder. Photo by John Porter

A few correctives to the Mathew Fraser article by Mike Hoolboom (August 2013)

In paragraph three: Warhol couldn’t have let a film camera roll for “hours” because the maximum length of a roll was 1200’ (33 minutes). Sleep was actually shot with a Bolex camera, and included a lot of optical printing and repetition. Most of his features were made with an Auricon camera that had sound on film (!) and ran 1200’ rolls. Many of Warhol’s films consisted of exactly two unedited rolls of film.

“The Funnel began with only one thing in mind: the exhibition of experimental films.” Well, no. Funnelites stacked the board of the Toronto Filmmaker’s Co-op back in 1978, hoping to take over the organization, only to find it mired in debt. The Co-op was concerned primarily with production and equipment access, which would have taken the Funnel in a very different direction. An integration of production, distribution and exhibition were always part of the Funnel’s mandate.

CEAC was not a tenant at 15 Duncan Street, it was the landlord. The notion that “The sword of Damocles had been hanging over government-funded CEAC for some time” is at best an exaggeration. Both the Ontario Arts Council (as the article notes) and the Canada Council, unilaterally withdrew funding.

“It was Elder, with his reputation as an academic and established filmmaker, who convinced government arts funding agencies to support the fledgling Funnel after the CEAC debacle.” Hahahaha. It’s not difficult to guess who the source of this juicy lie belonged to. The truth was that the Funnel inner circle, including Anna Gronau, Ross McLaren and Adam Swica, had been in conversation with the Canada Council when they were running the Toronto Filmmaker’s Co-op (before the CEAC collapse), and it was understood that some of the Co-op’s money would move to the Funnel.

“The Funnel’s annual budget is now $100,000 – one third of which is self raised.” Did the Funnel raise $30,000 in self-generated income? Nope.

Mary Brown, head of the Censor Board, describes Al Razutis’s film A Message From Our Sponsor as “it’s all hardcore footage” which is simply not true. It is largely comprised of mainstream sixties commercials advertising soft drinks and other consumer items.

Mary Brown: “The Razutis film is the only film that has a censorship problem.” The difficulties with showing Snow’s film Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen marks this as another lie.