(March 25, 2010, Ann Arbor, Penny W Stamps School of Art and Design)

Usually the term found footage is used for film or video productions that use images originally produced for some other purpose and by some other maker. Conventionally applied to productions from the marginalized sphere of experimental filmmaking, this practice can also be found in various other areas. Over the years, in music videos and commercials, on YouTube and even in big-budget, box-office hits, found footage has turned into a well-established standard, something global audiences are quite familiar with.

In avant-garde cinema, found footage films form a species of their own; since the early 80s found footage has been one of the most crucial and fruitful trends in this sphere. But even here there is not one specific, indistinguishable appearance of found footage films – as Christoph Settele states in the preface of his “Found Footage” reader, “the motivations for using found footage (…) are as many and as diverse as the aesthetic problems that arise from its use”.

One might add that there are also lots of moral questions and legal problems arising from the use of protected footage produced by some other maker. We still have quite diverse copyright laws in the countries of the European Union: while France does not allow any use of protected material as long as no licence has been granted, in Germany we have a specific paragraph that legalizes the artistic use of appropriated footage. However, certain conditions need to be fulfilled. Few artists know about this, and in the eyes of a broader public, the artistic recycling of found film material without any licence fees paid may still be considered exploitation or even theft. In the visual arts, on the other hand, appropriation and collage seem much more established and hardly questioned at all: this method can even be traced back to the early origins of collage in the Middle Ages.

When I made my first found footage film some thirty years ago, I had no idea how long and rich the history of this method has been in film as well. In fact, as soon as producers discovered safe means of duplicating existing footage in the very beginnings of cinematography, the idea of recycling entered the film world. When film stock was still very expensive, cutters were expected to have a collection of spectacular shots at hand that could be used in different contexts. In film, the question about what constitutes an original and what makes a copy is a rather delicate one, for the medium is based on the very idea of reproduction. If one considers the negative stock the original, what we watch on the screen is a copy.

Considering the long history and the extensive use of found footage, the lack of a full historical outline of this practice is striking. There is no overarching study or critical appraisal of the contemporary use of found footage. One of the reasons for this is the fact that found footage films do not form a species that can easily be located; there are numerous impure, hybrid forms of this method. The same is true for my own work that both encompases pure found footage films and productions that only include a certain amount of found footage, but mostly consist of original material.

William C. Wees is one of the few authors on the subject of found footage filmmaking. His definition of found footage excludes works like Kenneth Anger’s well-known Scorpio Rising (to be screened as part of the Anger retrospective on Saturday), a film that obviously uses a lot of found footage, but that is neither based on it nor is it all about it. For Wees the term “found footage” implies a visible reference to this particular practice in the work itself. According to him, a true found footage film highlights the fact that all or most of its imagery is taken from other sources and makes this one of the film’s principle points of interest.

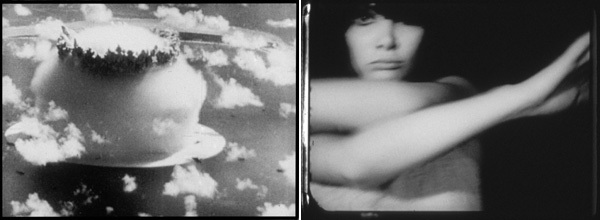

Found footage films do not only address specific subject matters in highly individual ways, but generally draw the attention to the body of the film itself, its material, the emulsion, to “the film’s own image-ness”, as Wees puts it. In found footage films the medium refers to itself – and it is this self-referentiality that makes found footage films meta-films analyzing, criticizing and often enough mocking cinematic conventions of representation. This is why found footage is both a continuation and a transformation of previous manifestations of avant-garde cinema such as the structural film that also referred to the medium itself, resolutely fighting its illusionism. However, with the boom of found footage films in the early 80s the focus of attention shifted from an iconoclastic attack to a thorough questioning of the contents spread on film, a critical exploration of its semantics.

No material seems too hot (or too toxic) to handle for devoted found footage artists. Scientific and educational films, newsreel footage and propaganda films, feature films, commercials, footage filmed by surveillance cameras, erotic and pornographic films: they all mingle in the hands of a found footage filmmaker, and they encounter each other in wild, impure mixtures of stylistic means and modes of representation. The footage may be derived from the early days of cinematography, like in some Nervous System film performances by Ken Jacobs, or it may be taken from contemporary pop videos, as in works by Jonathan Horowitz and Mike Hoolboom. The source material may be easily recognizable, but it may also be manipulated by methods of re-filming, by handmade interventions, mechanical or even bio-chemical treatment that transforms its pristine look into something very different from its original.

The conventional cultural hierarchies of high art and low art, bourgeois and popular culture – more obvious in European culture contexts – do not mean much to found footage artists. For the viewer of found footage films this means being prepared for a bewildering, daring, patchwork, a clash of often rather heterogeneous media material.

Found footage films demand a specific perception: they ask for a higher concentration, for the viewer can never feel safe with what he/she is being exposed to. Moreover, found footage filmmakers quite often take an ironic distance to their appropriated material; pastiches and parodies are quite common in found footage filmmaking.

At the same time, found footage film might be defined as an artistic form of applied film and media science to a certain degree. Conventional modes of representation are being questioned by found footage films, hidden subtexts are dug out, ideologies dismantled, subliminal messages are uncovered. “This act may cause revelation that leads viewers to reconsider the relationship between past and present, here and there, intention and subversion”, as the organizers of the 2009 Los Angeles Found Footage Film Festival explained. They named it “The Festival of (In)appropriation,” for the act of appropriating other makers’ footage is conventionally considered dubious (to say the least) in our society.

Found footage artists on the other side claim access to our common cultural heritage. But even their attitudes about what is appropriate and justified, and their understandings of where exploration ends and exploitation starts, are quite diverse.

In our collaborative work, Christoph Girardet and I cling to an individual moral code that keeps us from working with footage taken from films by artists working in a sphere close to ours. What is the use of appropriating images distinguished by highly individual artistic signatures, images that exclusively work within their original context? Instead of this, we prefer working with footage that has the spreading power and universal appeal to shape collective notions.

Sometimes a find can be so telling, that it does not ask for being altered at all. It is a crucial artistic decision whether to manipulate one’s finds or to leave them untouched (more or less) and to just exhibit them the way they are – like ready-mades. Ken Jacobs did so with his Perfect Film in 1986 – and he has found many followers in this radical practice. According to Jacobs, “a lot of film is perfect left alone – perfectly revealing in its un- or semi-conscious form.”

In 1994, Douglas Gordon slowed down Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho to a new duration of 24 hours. The mere act of changing the frequency of images made his audiences experience this popular, iconic movie in a radically different way. Gordon has never sold a slowed down version of Psycho that he does not own the rights of, but the idea only. Is this found footage any longer, or a contemporary example of conceptual art?

Sometimes a single shot only has to be lifted from its original context and – isolated from this – can be seen and enjoyed in its new, splendid isolation. Bruce Conner once compared footage like this to a gem, a jewel that needs nothing but a new and more appropriate setting to be allowed to shine and shimmer. This proves that it is not only an aggressive, deconstructive force that fuels the work of found footage artists. There is more than just the intention to criticize the normative quality of media, their distortions of reality, their repressive power that stimulates the artists’ interest.

Quite often found footage filmmakers are enthusiasts about their footage – and they lack all interest in degrading it. Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart, for example, produced in the 30s, is an early example of a found footage film created by a fan. Cornell was obsessed with the actress Rose Hobart then, who had made a small career in trashy B-pictures. Cornell’s film is nothing but a condensed version of Rose Hobart’s 1931 feature film East Of Borneo departing from the original narrative of this exotic jungle drama and turning it into an object of personal worship. His act of appropriating and transforming images produced by an industry for mass audiences into fetishes of his own personal cult was adapted by quite a few other filmmakers later on, who placed themselves into a Cornell tradition.

Lewis Klahr’s Her Fragrant Emulsion, the filmmaker’s tribute to actress Mimsy Farmer, Jerry Tartaglia’s Remembrance, an homage to Bette Davis, or my own film Home Stories, that derives benefit from a couple of movies featuring Lana Turner, obviously are not interested in their source material as samples of “toxic film artifacts” in the first place. In her essay “The Archeology of Redemption” (1993), Sharon Sandusky applied this term to all of those films that according to her should be dismantled, deconstructed and finally abolished by the work of found footage filmmakers.

However, not all found footage artists are driven by the intention to exorcise and execute their appropriated material. There may not even be the notion of a “guilty pleasure” when they playfully recycle images that might easily be proven manipulative and repressive. It is obvious that a practice like found footage filmmaking is both based on repetition and transformation. But repetition is much more than the basic tool of found footage filmmaking.

In the 80s, the artistic revision of the conventionally disfavored practice of repeating something also caused a revision of previous understandings of the supposedly essential task of the avant-garde: its challenge of breathlessly producing something never seen before, of exploring innovative means of cinematographic expression without hesitation, of exclusively devoting itself to novelty.It was mostly found footage filmmakers who more and more criticized this concept of being too easily exploitable by capitalism. Sharon Sandusky discredited this traditional understanding of the principal tasks of the avant-garde as “the heritage of our industrial society.” In contrast to a linear reading of history, she proposed a cyclical understanding of historical processes – in accordance with Mark Twain’s saying that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” The work of the found footage artist Sandusky considered crucial for helping us realize that certain problems that are usually considered historical may remain unsolved. This is one of the reasons I prefer to work with dated material.

The use of appropriated material has been the major method in my work since 1979; over and over again I have excerpted fragments of films made by other directors and offered them a new life. No matter how dominant this practice has been in my work, it has rarely been based on a system and it – hopefully – cannot be summed up in a brief formula.

Chance, as well as my ever-changing moods and shifting interests, have always been more crucial impulses to me than any binding artistic program or theoretical doctrine. Appropriating found footage has often been an almost physical reaction, like a gripping reflex; it is a practice full of relish. In some of my early films, I have especially enjoyed the moments of mingling appropriated material with original footage filmed by myself. Most of the appropriated material in these early films I used to collect in my own living room – with the remote control of my TV set. Footage collected like this reminded me of flotsam and jetsam; very rarely could I tell the original source after gathering bits and pieces of interest on videotapes. My attitude towards my material partially depended on the way I got hold of it; it does make a difference whether I find it in an archive after a time-consuming, elaborate research or if I run into it by chance. A find that is not predictable I consider more precious than any other one; it is like experiencing a very special, almost privileged moment. Such a – let me call it – magical moment is rare, and this is what makes it so precious.

An archeologist’s excitement unearthing ancient ruins could not be bigger than my thrill when finding the first piece of found footage for a new project. In the early 80s I accidentally discovered five deteriorated 35mm film frames in the dust of a Roman piazza. They showed a human eye, opened wide in panic. It took some years until the glance of this very eye fell on me again, this time from a big film screen; I then realized that this was the opening shot of Michael Powell’s psycho-thriller Peeping Tom from 1959.

Facial expressions of fear, panic and hysteria determine my film Home Stories from 1990; the reason for this emotional turmoil remains unexplained. Contre-jour, my latest joint project with Christoph Girardet, revolves around similar motifs as well. This is why both of these films might be considered late reflections on my Roman find. A precious accidental find like this, one that cannot easily be identified and that stays enigmatic for a while, usually causes a more enthusiastic reaction than a predictable archival find that is only the result of persistence.

Bored by viewing lots of mostly orthodox documentaries on the construction of Brasília during my research for my film Vacancy at the São Paulo Film Museum, I discovered a reel of 16mm travelogue footage shot by some amateur in the early 60s that was not considered good enough to be listed in the records. It instantly turned out to be the most crucial find for my film project Vacancy. The fact that it had been in use, that it was scratched and about to fall apart made it perfect for my meditation on the decay of a social and aesthetical utopia, its slow journey into a dystopia. A find like this is able to cause the “ignition start” for a whole project. Different material may soon surround it.

A single shot initiated a collection of maritime motifs of six hours for my film Sleepy Haven (1993). For each of my projects I usually build up an archive of sounds and images, a pool that I can immerse into, but that I may also get drowned in at the same time. I had already gathered an even larger and less focused archive of sounds and images for my film The Memo Book four years earlier, back in 1989. Such an accumulation of material produces an alternating current; shots are facing and corresponding with one another; accidental acquaintances of sounds and images turn into firm, elected affinities, Wahlverwandtschaften. Sometimes these temporary montages on reels or tapes generate unforeseen ideas for the final cut.

This is similar to how Bruce Conner worked: “I snip out small parts of films and collect them on a larger reel. Sometimes when I tail-end one bit of the film onto another, I’ll find a relationship, that I would have never thought about consciously – because it does not create a logical continuity, or it does not fit my concept of how to edit a film.” In general, the importance of chance and an acrobatic juggling with images in found footage filmmaking seems underrated to me. Found footage may be an effective tool of cultural criticism, a powerful weapon for striking back, but it cannot be separated from playing and messing around with appropriated material, with the joy of bricolage.

In The Memo Book (1989), the appropriated material was used in order to extend autobiographical concerns; it helped me implant introspection into a common vision. This synthesis underlines the dialectical relation between one’s own vision and a collective catalogue. Most of my films deal with intersections of public and private spheres, mingling images from the public domain and images taken from the domestic space, home movies for example.

In my films, found footage is often used in order to intensify emotions which are inherent in my own footage in a less expressive and articulate way – without ridiculing them – notions such as sentimentality or high drama. It would have been easy to stress the contrast between the high production values of the appropriated Hollywood images, its lushness and stylistic elegance and my own low-budget aesthetics. Instead of stressing this obvious difference, I decided to do away with it by not using the original Hollywood footage but refilming excerpts of broadcasts of Hollywood movies off the TV on grainy super 8 with a shaky, hand-held camera. All of this film’s footage was shot on the same stock. During refilming my own hands and feet served as a means of framing: you can temporarily see them cover up parts of the found footage.

In order to connect the appropriated footage and my own more closely, the colours were matched. After this procedure it is still obvious that the Hollywood imagery is the result of a costly industrial process. However, I never intended to discredit it as being false, manipulative or repressive and to set it against my own, allegedly true, authentic experience. “My films are no different from what I experience,” Bruce Conner once stated. Working on The Memo Book I realized to what extent my own emotions were determined by notions spread by the media, however “toxic” these may be. Due to the long time span I dedicated to the production of The Memo Book, I was able to take a distance to my own footage and watch it the way I watch found footage. This self-created distance may finally raise the legitimate and essential question: What precisely are my own images at all?

In this creative process of comparing my self-image with media images, a growing self-awareness mingled with a sometimes thoroughly changed self-perception and new ways of representing the self. This way, I avoid talking about myself simply as a means of self expression: I use myself as a vehicle instead and open the work to the viewers. There is a certain playfulness involved that helps to blur the lines between fact and fiction, me and not-me.

However, in The Memo Book I tried to be as subjective as I could; I even took the found footage personally. This also had to do with the modes of my production that are closer to the ones of visual artists than to those of directors connected to the film industry; in my case, there is no control body except for myself.

In The Memo Book, actress Kathryn Grayson can be seen moving in front of a back-projection of highly dramatic evening skies. In this excerpt from one episode of Vincente Minelli’s The Ziegfeld Folies of 1944 she is singing a song about beauty, stating that “there’s beauty everywhere for everyone to share”. In the German version, this message is literally being inscribed into the image as a subtitle. As for me, Kathryn Grayson’s message was an open invitation to share the bizarre beauty of her very own representation. I have a certain preference for images like this one, calculated images, both emblematic and overcharged, campy, over the top, images meant to impress and to overwhelm. I am interested in messages that are only too obvious, images that tend to offer too much, so I can take something out of the abundance of their semantic overload. The same could be said about the (over) acting style of Lana Turner, as Molly Haskell states, Lana Turner “exaggerates the exaggerations.” My short film Home Stories (1990) is dedicated to her mannerisms in particular and to the mechanics of her genre, the melodrama, in general. By means of parallel montages, this film eliminates the individuality of different characters forcing them into only one role: the role of the victim. This method reveals how limited conventional schemes of cinematic representation are, simultaneously illuminating the “limitations of life” mirrored by them.

The fact that the footage used for Home Stories was all easily compatible helped me create my own condensed miniature melodrama as much as it allowed me to become a dissecting, analyzing film scientist. All of the films mentioned so far, The Memo Book, Sleepy Haven and Home Stories, are part of a program devoted to six of my early solo projects that will be shown as part of the Ann Arbor Film Festival on Saturday.

In 1999, I began to co-operate with an artist friend of mine, Christoph Girardet. I shifted from analog filmmaking to digital video and I started having my work exhibited in the art world more and more. The concept of a shared (or doubled) authorship, the state-of-the-art technical options offered by the digital revolution and the yet unexplored possibilities of a spatial exhibition of my new work were new challenges. However, these new conditions also allowed me both to continue my previous artistic practice more easily and to expand it.

The impact of a strong autobiographic background, crucial for most of my individual films, has obviously decreased in my joint projects with Christoph. Nevertheless, there is a personal background to all of them and we generally start a new project contemplating the common challenges in our lives, whether they are new or recurring ones.

This past decade has seen the emergence of a variety of new sources for audiovisual materials, as a result our new works were generated under significantly different conditions than our solo works from the 90s. Whether it is Amazon or eBay, the Internet Movie Data Bank, or the release of the Prelinger Archive on archive.org: all this has been helpful for a more elaborate research for found footage projects and has made access to even distant and obscure materials much easier. This is why most of my recent found footage works could be based on the viewing of several hundred movies.

At the same time, working with found footage has turned into a common cultural activity and the subversive potential it had formerly gained within experimental cinema seems to be fading away gradually. Nowadays, YouTube is full of home made mash-ups – and major production companies and distributors such as Paramount Pictures, New Line Cinema and Pathe are even commissioning found footage clips by artists’ groups such as Addictive TV who were asked (and well paid for) remixing shots of Slumdog Millionaire, Iron Man, and Shoot Em Up in viral trailers meant to reach those parts of the web other trailers would not reach. Obviously, capitalism’s ability to absorb, to swallow everything, may even turn an artistic technique apparently subversive into just another marketing tool.

These days, most images have a long history of being used (and abused) for a broad range of purposes. In societies infused with images, we cannot but diagnose a corruption of meaning, a preceding emptying of the original visual semantics. The simultaneity of an increasing circulation of images and an accelerated loss of content has something exhausting about it. The image industry has turned us viewers into customers looking for quick-fix satisfiers while withholding true satisfaction. It has become increasingly difficult to subvert this mechanism using images produced by this very industry.

Nevertheless, Christoph and I have continued to employ this technique in ten joint projects developed since our first artistic co-operation in 1999, The Phoenix Tapes. I am about to present three of these works; however, just one of them, Kristall, is a pure found footage montage.

Mirror, for example, produced by Christoph Girardet and I in 2003, uses no visual quotations and contains not a single moment of drama. This time, we devoted ourselves to the moments in a movie before and after a crucial speech or event: the time in-between times. Researching those elegantly staged moments of social alienation in the films of Antonioni’s Italian Trilogy, we came across a phrase of this director: “The characters in a tragedy, the air they breathe, the settings, are sometimes more absorbing than the tragedy itself, as are the moments when the plot is at a standstill, the dialogue is silenced”.

The sense of fragmentation generated by our film is increased by a mysterious division: you hardly notice it at first, but there is a vertical fissure running down the centre of the image. In fact, each of the images is composed of two images, separate halves that unite to create one motif. Without a centre, a meeting point, the figures are forced even further to the edges.

The frozen tableaux of Mirror are animated by light alone, which creates connections but also isolates the figures and separates them from the surrounding space. Mirror was conceived as a vague echo (in a sotto voce voice), a reflection of films of a specific era of European arthouse cinema. While we tried to push our interest in found footage in a new direction here (the only citation is Monica Vitti’s voice taken from the soundtrack of Il Deserto Rosso/The Red Desert), we returned to our established practice of telling a new story out of the fragments of numerous old ones three years later.

Kristall (2006) creates a melodrama inside seemingly claustrophobic mirrored cabinets. Like an anonymous viewer, the mirror observes scenes of intimacy. It creates an image within an image, providing a frame for the characters. At the same time it makes them appear disjointed and fragmented. In Kristall, this instrument for self-assurance and narcissistic presentation becomes a powerful opponent that increases the sense of fragility, doubt, and loss.

Like most of our projects, this one is based on a large archive of pertinent shots, in this case: a vast collection of shots of mirrors. We were interested in this motif because it belongs one the most used and abused tropes in art and media history, and we were trying to figure out if anything of its previous symbolic charge could still be activated for our study of reflection and refraction.

In his book Ways Of Seeing John Berger states: “The mirror was used as a sign of women’s vanity. Nevertheless, there is an essential hypocrisy in this moralizing attitude. You paint a woman naked because you enjoy yourself looking at her. If later, you put a mirror in her hand and title the painting Vanity, you are morally condemning this woman, whose nakedness has represented for your own pleasure. (…) But the real function of the mirror was really other. It was made for the woman to accept treating herself mainly as an spectacle.”

During our research of some 130 movies we realized that the way women are being represented in front of a mirror in mainstream cinema may be understood as a comment on their allegedly inherent narcissism. Moreover, we made the observation that quite often when a woman can be seen facing a mirror in such movies, her reflection gives evidence of the fact that someone is missing. In conventional narratives, this is usually the male counterpart of the female protagonist. The staging of male characters facing a mirror, however, is remarkably different: here, somebody is actually facing his physical self, his fear of disappearance, his monstrosity and mortality. All of the shots of our film contain mirrors, and all of them were projected onto mirrors and then refilmed by us.

Contre-jour, the last film of this program, juxtaposes both found footage and original material shot by us on 35mm film. It is a reflection on visual perception that adapts formal elements of the flicker film. This is why the film is a bit of an eyesight test as well: “Blurs, flashes and stroboscope montages disintegrate reality into shadowy images that inflict pain on the eye of the beholder. The look with which we comprehend the world and which it casts back at us in response breaks up in Contre-jour into disquieting fragments. Blind spots gape between self-perception and the perception of others.” (Kristina Tieke)

The central character of Contre-jour is the eye: “as a physiological perception of shape, space, colour, light, dark, as the source and reflection of what sight doesn’t see, as a fragment of a body condemned to remain in the shade, as a substitute for a tactile relationship with the world, as a glance, a sexual impulse, the fixing of desire. Turning the eye on itself means fragmenting the world, dislocating its forms, extinguishing consciousness,” as Yann Lardeau put it in the catalogue of the Paris Cinéma du Réel festival that the film was screened at yesterday.

This definitely is not a film for the optic neurotic; its flicker sequences may even cause epileptic seizures if you are sensitive to this. Like all other viewing experiences, this is going to happen at your own risk. Nevertheless, I hope you will enjoy the films.

Mirror, 35mm CinemaScope, 2003, 8’10”

Kristall, 35mm widescreen, 2006, 14’30”

contre-jour, 35mm widescreen, 2009, 10’40”