Funnel Days: an interview with Sharon Cook (August 2013)

Sharon: I attended the Ontario College of Art for four years. I graduated in Experimental Arts in 1981. I didn’t take four years of Ross McLaren’s (film) class though, maybe one or two years. The prevailing attitude of the Experimental Arts department back then was one of unofficial casualness and I didn’t attend a lot of Ross’s classes.

Ross was a young teacher with a trademark leather jacket, he was passionate about film and open-minded. He had a relaxed teaching style but with a conscientious attitude that always supported the underdogs. There were no weekly assignments, we just made films. Ross would show films, after which a discussion would ensue. He would offer some technical instruction on camera operation or lighting. He used to hand out photocopied material on technical info. Ross’s class was probably my first exposure to “experimental” film. However, I just wanted to make films and was less concerned with a genre or the label “experimental.” For the class I made a film that was screened at the Funnel, part of an OCA student showcase. I was impressed with the fact that you could make a film and have a place to show it and found the response to the film encouraging. The film was titled The Dot Film and it was shot in super 8. It consisted of shots of polka dot fabric blowing on a rooftop. The soundtrack was shortwave radio. This must have been my first trip to the Funnel. I liked the red plush theatre seats and as a screening venue I thought it was great. I found the atmosphere to be friendly and creative. Incidentally, I was playing in a band called Space Invaders at the time and ended up doing a benefit concert for the Funnel at Scadding Court Community Centre. My involvement was keyboards, guitar and vocals. The band never played at the Funnel, though I vaguely remember doing a film performance there. Ross asked if I would play at the benefit.

I also created a film installation piece in that class which involved super 8 projections on a sculpture. It was titled Duck Blind. Duck Blind looked like a duck blind. It was a rectangular yellow cardboard sculpture approximately seven feet long by four feet high with a slot cut out. The film loop that was projected on it was a static shot of the “duck blind” and then it would fall down revealing a Lake Ontario shoreline. The image was matched up in size to the sculpture. I don’t remember if I had seen film installations previously, I just conceived the piece that way. If there were other students doing film installations I don’t recall. The fact that film could be projected on any surface opened up many artistic possibilities for me.

Years later I became a substitute teacher for Ross’s class, and I remember getting a powerful headache because the students were so intense in their discussion of the films. Ross’s classes created a climate that was very constructive and supportive, very encouraging to experiment in unique forms of filmmaking.

Mike: “Experimental” film was a popular term in the early eighties. You name it as a genre (like the Western), am wondering if you could describe the traits and borderlines of this genre, and whether your movies fit. Did you ever make something that you would say isn’t experimental, for instance, and what might that look like?

Sharon: The short answer is that experimental film is unconventional cinema made unconventionally. I think that generally speaking the term refers to non-commercial, non-Hollywood films, films made with artistic intentions. What I mean by “artistic intentions” is films where artistry trumps conventional conception. I believe most film genres can be experimental; for example there could be experimental westerns, though none come to mind. Animations can be experimental though I am not sure about documentaries. Again, for me, the filmmaker’s intention is an important factor.

All of my films are experimental except for one narrative that could be considered a short. It is titled Manganese! (10 minutes black and white, 1987). It uses guinea pigs as actors and has a live accordion soundtrack. It was shot in black and white as an “old time” silent movie with intertitles. I wanted to make a film with guinea pigs as actors. The story is set in France in the late 19th century. It is about a struggling painter, Elzear, who is trying to get a painting into the Grand Salon. There are guinea pig-scaled sets such as a provincial cottage where Elzear lives, and a tavern. Azelie, played by another guinea pig, is Elzear’s model and poses for him. A painting is created. The guinea pigs were quite humorous, in fact there is some camera jiggling motion because I was laughing when it was shot. Maybe it is an experimental film.

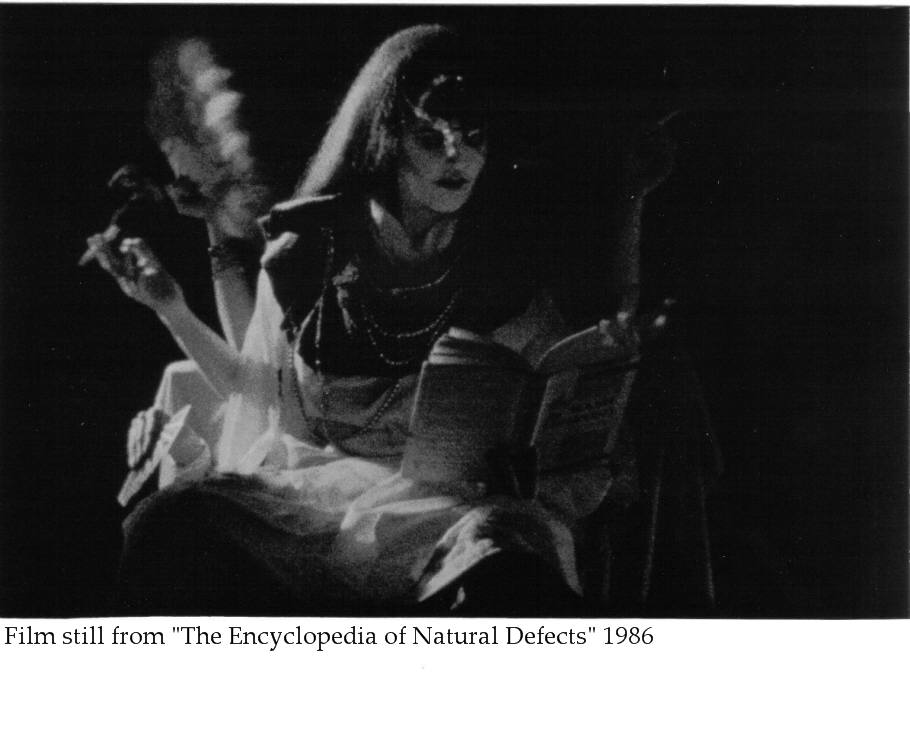

Mike: Your longest and most ambitious film was named The Encyclopedia of Natural Defects (35 minutes 1986). You described it this way: “From a sea cave in Labrador a six-armed oracle ‘hosts’ a variety of vignettes. Deer imaging is explored by a woman entertaining an antler, famous paintings are re-enacted, while most of the spoken dialogue is pig Latin. In this quasi-musical, the sound track is an original score with songs ranging from “The Ballad of The Encyclopedia of Natural Defects” to “Ya Ya Mmm, Ya Ya uh huh.” Were there movie inspirations at The Funnel that prompted you along the way, that worked as spirit guides or unconscious mentoring societies? I remember a lot of dreamy costumes and elaborate effects (it’s been a long time since I’ve seen it), can you help bring back a little more of the movie. If you had to answer this dreaded question: ‘what is it about’ what would you say?

Sharon: The reason for the title “The Encyclopedia of Natural Defects” is twofold. It acts as a title and as an end title. For the first letters of the title spell “end” or E.N.D. which is used at the end of the film as the other letters fade away leaving only “The End”.

There is a shot of smoke stacks that becomes the film’s front leader as a way to exaggerate the length of the film. Its purpose is to go beyond the normal screening length of the film and to control what comes before the film, as well as what comes after. In this case some exit music accompanies black leader at the end. So the film’s beginning and end are deliberately blurred. For me this hints at the cyclical quality of film and of life.

The “Natural Defects” refer to those psychological qualities that make up an individual, and how in some cases they are seen as defects but in fact are “natural” to the individual. “Encyclopedia” refers to a cistern of knowledge, in this case knowledge that is obtained intuitively, the “knowledge” of images that are portrayed across a screen.

The film opens with a shot of a six-armed woman “oracle” playing three instruments at once in a cave with ocean waves off to one side. This scene is returned to time and time again as the oracle is seen reading, playing cards, speaking, drinking beer and yawning. The oracle makes no overt proclamations, the “prophecy” is on a subtle level, one of mood presaging mood through the juxtaposing of images. Although it is not mentioned, I think of the oracle’s sea cave as being in Labrador because that is where I imagine a remote and exotic location in Canada.

There are re-enactments of famous paintings such as Ingres’ Odelisque and Sleeping Venus. Other images include a scorpion in a hand, a hand-drawn pigeon between two cats, and many other seemingly unrelated images. I think of the film as an experimental musical for there are songs and musical selections that are central to it. “As I walk through time and space, who are you to read my face” is one that directly questions the audience. In fact there are several instances when the film speaks directly to the audience, for example when the oracle speaks, “You are you, we are we, we are we-they…”.

For me the film is about a lot of things; an exploration of cinema, of trying to create coherence from disparate elements. It is a concoction of images without a discernible plot, but I see an underlying structure that is mainly supported by the music and songs. The main song “The Ballad of the Encyclopedia of Natural Defects” was sung by a friend and it is at the end of the film, accompanied by black leader with fleeting glimpses of a couple dancing. The songs and music were written during the production of the film.

In one sense the film is about the freedom to choose images at an intuitive level rather than being based on a script. It is about the creative process and where it meets the filmmaking process.

All the films I saw at the Funnel influenced me, and that was a lot of them, especially when I was the programmer there. The myriad of images and techniques no doubt had a role in the production of my film work though it was primarily unconscious. I was in the audience for one screening of this film when it angered a viewer so much that he took to shouting at the screen. As he stood up and left, the part of the film that has an angry face shouted back at him all the way out. I have noted either a very favorable or a very unfavorable reaction to the film.

Mike: In 1986/87 you were on the Funnel’s board that fired John Porter, who was the programmer. He told me that the board was concerned because he had put on an open screening, long forbidden by the dreaded Censor Board, though he had received written consent from the Board, who very likely didn’t examine the mountains of paperwork they received all too carefully.

Sharon: I hated firing John Porter but it seemed like there was no choice. I think he remembered it right – something about an open screening. At the time I was vice president of the Funnel so the task fell upon me, although I was not alone when we did it. I don’t remember Melinda’s dramatics. I then became the interim programmer. At first I was just going to do it until someone could be found, but I liked it so I stayed on.

I volunteered to be the interim programmer. There was no interview for that. However, when I stayed on to be the official programmer I had to go through a hiring committee procedure. There was an interview with a small number of people. I only have a vague memory of the day we fired John Porter.

By the time I became the programmer, the Funnel was already well established as a venue for experimental film and related media. Good international connections had been forged so it was relatively simple to organize visiting filmmakers to screen their work in person. But there was a problem. Audience numbers had been progressively dwindling. I remember apologizing to Adele Friedman for the poor turnout for her screening. Unless you were Stan Brakhage (a sold out show), you weren’t going to fill the theatre. The solution it seemed was to move to the Queen Street West district, and so the new theatre was built on Soho Street. I remember slightly increased foot traffic at the new location. The numerous films that I programmed are now one giant blur and oddly I remember the filmmakers more than individual films. I remember things like how one filmmaker was aghast at having to eat at a food court and drink from a can before a screening at the AGO.

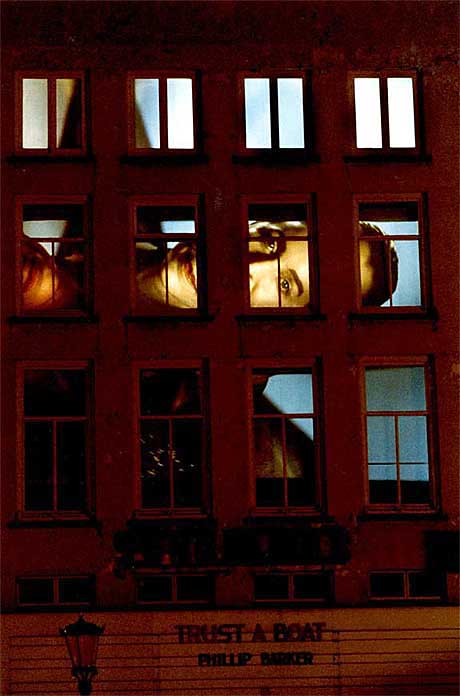

Of course I remember local artist Philip Barker’s ambitious live projections on a downtown building (“Trust a Boat”). I always enjoyed the local “New Work Showcases” and the “OCA Nights.” Every film had an impact on me. As a programmer I tried to be open-minded, showing films that might not be personal favorites, but that had deserving reputations. In this way I always thought that it was up to the audience to decide a film’s merit or even destiny. Incidentally, I remember writing a cheque to you for a screening in the name of your alias (Crane?) because that is what appeared on the program. Looking back it was an engaging experience, now an assemblage of mostly fond memories. I only wish I had spent more time on the pool table that sat in the production studio. It would have helped me, now that I play a lot.

I took over the radio show on CKLN-FM in Toronto from you Mike, and didn’t have any help putting it together. I called it “The Funnel Broadcast.” It seemed to polarize listeners — either you liked it or you hated it. It was experimental radio (if there is such a thing). I treated it as another media to explore. Soundtracks from experimental films were played and I created original sound collages. Filmmakers were interviewed either live or on tape. Also I did a series of one minute workshops focusing on some technical aspect of film. It was a weekly half hour show on Wednesdays. Sometimes people would phone me directly in the booth to complain about what they were hearing. I am not sure how long I did the show , but I gathered from all the complaints that it fell upon the director to cancel it. I was told not to show up the next week. I enjoyed doing the show.

Mike: The Funnel had been at King Street for nearly a decade before it moved to Soho Street in the fall of 1987. Programming resumed in the new hand-built theatre in February 1988, the seating had been reduced to fourty because of fire code regulations. Did you help build the theatre, can you talk about what that was like? This is still a deeply mysterious phase of the Funnel’s life, if you could shed some light that would be really great.

Sharon: The decision to move to Soho Street was a favored one amongst board members, although there were outsiders who warned against it. I just remember some older film artists warning against expansion for an artist-run centre. It was a board decision to move. And yes the primary reason for moving was to attempt to increase audience numbers. I didn’t physically help build the new theatre although other members did. I was more involved with the planning of it. A contractor was hired to oversee construction (electrical elements, etc.). The new location seemed attractive at the time. I don’t remember why the number of seats was reduced. To help defray the cost of rent, the so-called production studio was rented out as a theatre rehearsal space. I don’t recall the fate of the film processor. Soho Street was a nice facility — fine theatre, good offices, attractive lobby gallery. Too bad it didn’t last.

I remember some big shows at Soho Street, there was a large turnout for a performance by an artist’s collective from Thunder Bay. British and Australian films were memorable. One of my films, Manganese!, premiered there. We used to have board meetings around a pool table. The office was fairly functional. I was not at Soho Street very long due to a disagreement I had with the board so I do not know specifically why the doors eventually closed. I had already resigned. I don’t think anyone knew that the Funnel would close. Perhaps I wasn’t surprised because I thought that the board had “bitten off too much.” The move and larger space was a huge undertaking. My disagreement with the board had something to do with the financial direction the board wished to undertake. I don’t remember exactly the nature of my disagreement with the board but I felt that I could no longer remain. I think I left on good terms though. Soho Street had a lot of potential, too bad it closed.