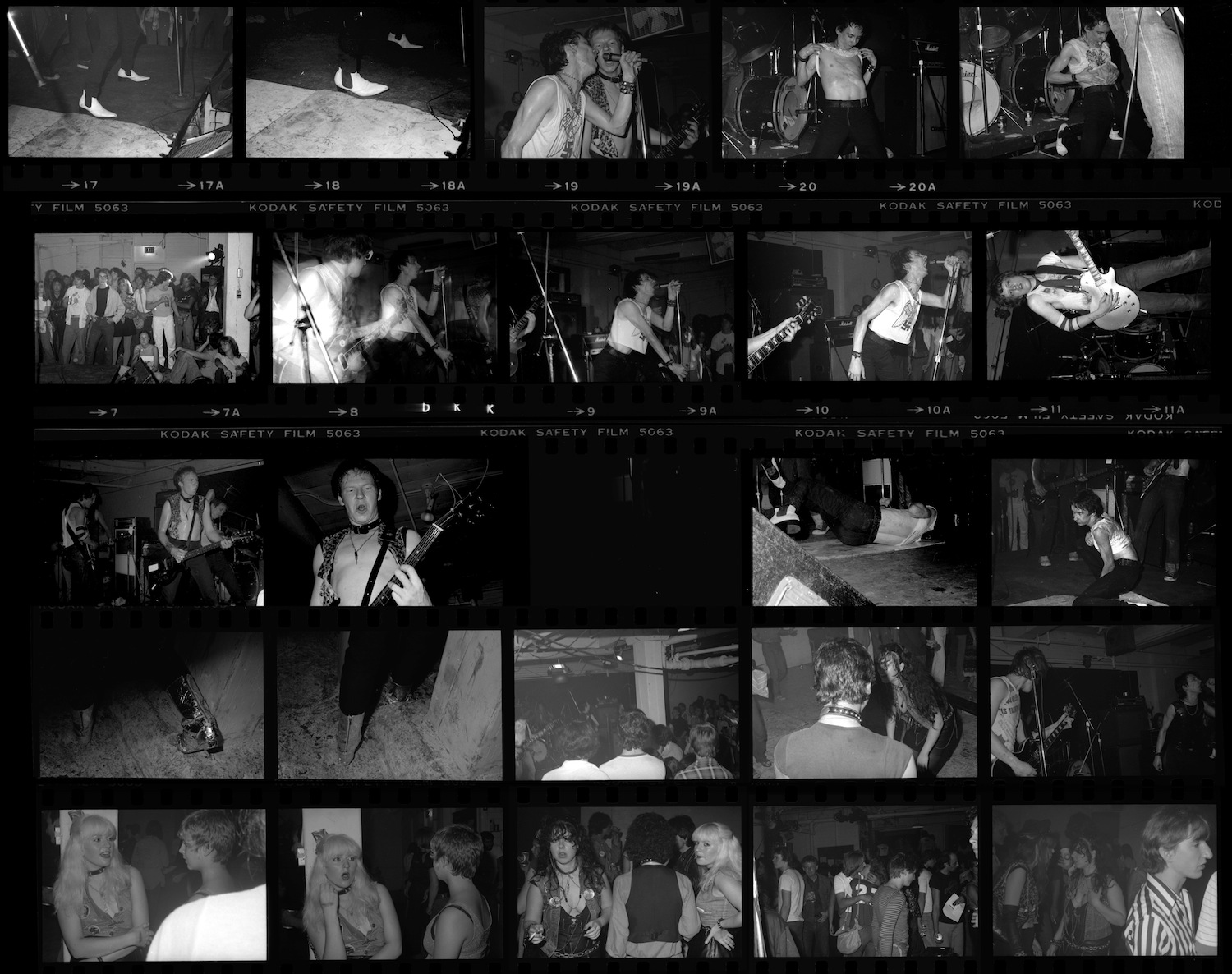

Fifth Column (band): Caroline Azar, GB Jones, Kathleen Pirrie Adams, Janet Martin

photo by Edie Steiner (1983)

Mike: Dot Tuer described the Funnel (Toronto’s once-upon-a-time underground movie theatre) as a modernist utopia project, meaning that it imagined a space carved out of a small and collective imagination that would create a space entirely separate from the mainstream consensus, or even other alternatives. Other examples might be gay bathhouses or punk rock.

Kathleen: This morning I was thinking about what remains of the idea of the alternative…. I remember how exciting it was to participate in and discover hidden parts of the culture that had very distinct purposes, but whose delivery vehicles were mysterious. They were entirely new horizons for thinking about culture—astounding for a young person! Many of those communities were vibrant in their initial years and then seemed to produce their own pseudo-institutional lethargy. I continue to find it distressing that when alternative cultural spaces become established, and gain some traction, they reproduce some of the worst habits of mainstream culture: that is, monopolizing resources for repetitious activities, worn out hierarchies of value, cliques, territories…. New initiatives need ways to attract new people and that’s when things are exciting. But then networks contract and become inhospitable.

My primary allegiance was with music culture, film was part of a broader context so I didn’t seek out the same sense of belonging within the experimental film community. But I think that it’s true that the Funnel makes a nice parallel to punk rock. Initially anyone can come and participate, but fairly quickly there’s a clear sense of who is inside and who is not… In the music community I felt inside, but I also felt that I needed stuff from outside. I liked the hard work of trying to understand complicated ideas, difficult texts. Urban development, religion and stuff from my own cultural background were interests that weren’t really central to what I shared with my friends at the time. But probably everybody was juggling…

Mike: How did you hear about the Funnel?

Kathleen: I have a very clear memory of walking down through the little park across the road when the Funnel was on King Street. I came from Scarborough and was really excited, thinking it was such a cool location. This was probably 1978 or early 1979 and I think I was going to a screening of Michael Snow films.

Mike: You were still in high school then, were there others there so young?

Kathleen: I don’t think so. Not until I started bringing some more of my friends! I thought everyone should come and see these remarkable wonders.

Mike: Mike Snow’s short movies can feel long, and they’re difficult even for connoisseurs. What did you make of them as a teenager?

Kathleen: I found the focus and concentration of Wavelength’s 45-minute zoom across a room very beautiful. It was an exploration of space without characters, there was nothing cliché about it. At the film’s end, I found the visual pun of the still photograph of the ocean very funny. I loved the sparseness of it, the fact that I was left to my own devices to inhabit the represented space.

Mike: Were you already making music?

Kathleen: I wasn’t in a band but I was learning how to play. I had been going to see bands since I was thirteen. I was into a lot of different kinds of music. Punk rock followed glam rock and I was also interested in reggae and funk at that time.

Mike: Was there a connection between the alternative music scenes and the alternative movie scene at the Funnel?

Kathleen: The Funnel was a space of underground art activity and it felt very aligned with the emerging punk rock scene. In the spring of 1977 I started going to the punk club, the Crash ‘n’ Burn on Duncan St. where the first Funnel screenings were held. I saw The Dead Boys, The Diodes, and The Poles might have played there as well. I saw the B-Girls that summer but I think it was in another location… The Crash ‘n’ Burn was this raw basement space on Duncan Street. It was dark and unadorned—not rat infested but industrial. There was just a small stage, some washrooms and a table that was probably the bar. It might have been one of the most exciting clubs I’ve ever been to. (Funnel founder) Ross McLaren was always at the Crash ‘n Burn so I guess for me he was the link between the two scenes. That’s probably how I hear about the Funnel.

There were also events upstairs at CEAC (on the fourth floor of 15 Duncan St.). I remember going to a lecture by French philosopher Bernard-Henri Levy. He was a big deal at the time. He had come to announce the end of revolutionary possibility, and that seemed to disturb those who were hosting the event. He said that the class revolution was an obsolete framework for emancipating the human spirit. That’s my recollection anyway. As a wanna-be high school revolutionary I was a bit shocked as well. Much of what I was experiencing was beyond my understanding but that’s part of what made it so exciting. Age is significant in terms of the question of expectation. There was an appetite for new information. My way of finding out about things was to go and see them. There was no internet. I was just googling with my feet.

During that period there weren’t fifty cultural events you might go to on a given night. There might be two bands playing: one at the Horseshoe Tavern, another at the Beverley and that would be a big night! There was other stuff though: the Revolutionary Workers League hosted talks; there was an interesting theatre upstairs at the Soho Cabaret, and the Music Gallery was active, that was another place where it was possible to go and see avant-garde culture in action. Maybe having fewer options made cultural life more interdisciplinary.

Mike: Is there any relationship between your becoming part of (all woman, experimentalist post-punk band) Fifth Column, and the Funnel?

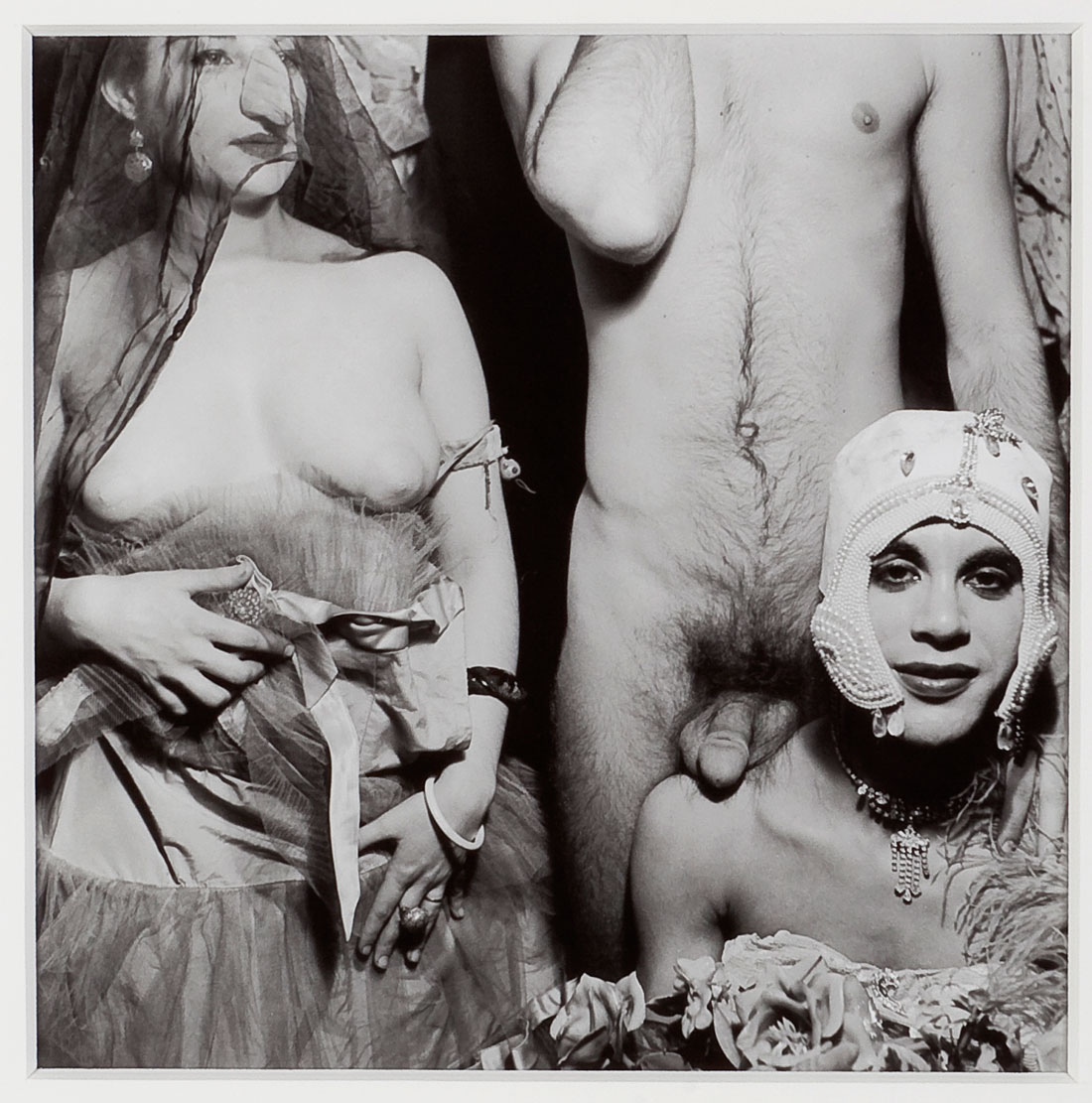

Kathleen: For me, yes there was. I’d been making music and trying to put together a band and then started playing with GB Jones and Caroline Azar and Janet Martin, the original members of Fifth Column. GB was at the Ontario College of Art, was very knowledgeable about art. We had a shared interest in Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground. She was the first person I met who already knew what the Funnel was and really understood what was important about linking avant-garde art practices and subversive lifestyles. The Funnel was important for feeding that impulse. We saw Vivienne Dick’s films and I think we both really related to her interest in transgression, in girls using violent imagery as a tool for feminism. That was our punk rock.

Mike: Did avant-garde art and subversive lifestyles necessarily go together?

Kathleen: It was the heart and soul of what that band was about. Fifth Column wasn’t a hobby. You were in Fifth Column, you didn’t play in Fifth Column. We were a group of people trying to develop an alternative sensibility, inventing our own version of feminism, creating art and music as a way of speaking to the world and making a place for ourselves in it. Our subversive agenda was connected with experimental art practice and it was core to our shared vision. Our ambition was to create a world outside the mainstream, outside the world we were familiar with, and to some degree we were successful in doing that. We worked to create an alternative context to ground our artistic practices and also to develop different ways of thinking about the world and ourselves. We lived together, spent most of our social time together, and of course we made music together. We generated different kinds of projects: zines, music and videos, and forged a community with other artists who were trying to remake the world.

Like many other people involved in subcultures the immediate community was our principal way of interpreting and understanding the world… When Caroline Azar joined the band she immediately brought her friends into the fold. Caroline, Midi Onodera and Candy Pauker had gone to high school together. Candy was a zine maker who set in motion a lot of important fanzines. Midi was studying at the art college and had quickly established herself as an experimental filmmaker. Everyone in Fifth Column brought a different influence: Caroline had a background in theatre, Janet had studied classical music, GB was a photographer and video artist. Our friends extended that multi-media thing further: John Brown and Marc de Guerre were painters and made videos, Pat Cummins was a photographer.

Mike: So one could be part of the collective project without being part of the Fifth Column band?

Kathleen: The band was a focal point, but there was a whole network of friends surrounding and supporting it. And then there were other bands Rongwrong, The Party’s Over, Woods Are Full of Cuckoos, The Diner’s Club…

Mike: Did you feel you were each other’s first audience?

Kathleen: Yes, even though people were doing different things. There was an incredible amount of sharing and overlap. Fifth Column played house parties at first and then the first time we played a public gig was at the Subway Room at the Spadina Hotel, another space where music, performance and video art intersected. Our opening act was Andy Payne who read a sonnet. It sounds ironic now but it wasn’t done with any sense of irony. He was a part of our scene and asked if he could read some poetry. We thought: why not?

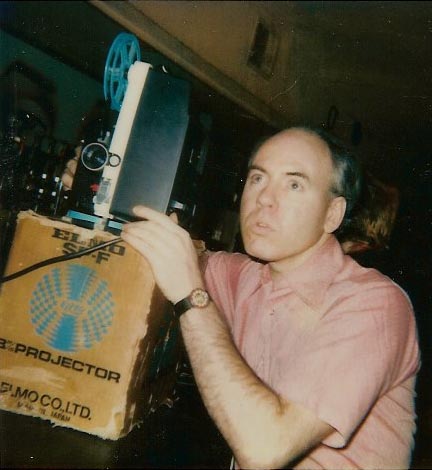

Early in our performance history we made a connection with John Porter at the Funnel. We invited John to screen his super 8 films on us as we played. It was an obvious homage the Velvets and Warhol. We were interested in the idea of a multi-media experience much more than we were interested in fitting the conventional rock star mold. I think the first time we did this was when Fifth Column played a benefit gig at the Funnel in May 1982.

Mike: I think that as people get older time evaporates while the shared ideals you’ve talked about require major face time.

Kathleen: In addition to the evaporation of time there were other kinds of socio-economic changes. Toronto during the seventies and early eighties could be a relatively cheap place to live. There was a ready supply of semi-abandoned industrial space that meant you could make music, movies or art without disturbing too many neighbours. You could get by bartending or waiting tables two or three nights a week. That became more difficult when the real estate boom arrived in the eighties. That was a huge stress for people and it became much more challenging to live in a free-floating way, or configure your domestic life in relation to community affinities.

While I had some good fortune during that period, I also had pretty low standards that made it fairly easy. I lived in a place with no heat on the weekends. That was doable, that was the cost of having a place that was cheap and central. But I knew others who were evicted two and three times in the course of an eighteen-month period. Higher rents ate away at our most important luxury we had become used to: free time. This was also a period before people invested so much in what they consumed. It was very unusual for anyone who lived downtown to have a television or a car. People cared about what they wore, but it was almost all second hand, being creative with your clothing was part of that lifestyle. That was the other big luxury we enjoyed: urban living before brand culture took over.

Mike: Before the internet, the question of who I might be, or who we might be together, had to be done in specific architectures with other people. There was also the hope conjured by scarcity and the possibility of anticipation. At the Funnel, many of us had only read about these difficult movies, or dreamed them after seeing a still. There was an urgency to go and see them because access was rare.

Kathleen: Yeah, you were lucky if you knew someone who had seen Kenneth Anger’s films or Warhol’s Chelsea Girls.

Mike: You would buy them a beer and make them tell it to you shot by shot.

Kathleen: These things had legendary status and it meant something to have experienced them. You’d make sure you saw them if you had the chance. On the other hand you’d sometimes be going to the Funnel or clubs like The Edge with next to no idea about what you were going to see. A street poster had an interesting image or a band had an interesting name, you might tear it down and show your friends and just go to find out. It was a bit random but the possibility of encountering something entirely new was exciting. I had no compelling reason to go a see David Rimmer’s films, for example, and almost as little reason to see Glen Branca… But who would I be if I hadn’t?

Mike: That feels like a deeply non-consumerist impulse. Opening to unexpected experience feels counter to the notion of buying reliable experiences, or purchasing something that will fit into or confirm who I already am.

Kathleen: In a sense I was a voracious consumer. Exploring culture from different disciplines, trying to put together a bigger picture. I wanted to understand the immediate past of cinema and rock and roll, trying to imagine what might happen next. That was enough to keep me searching and looking and consuming. So in one sense I was very much a consumer of culture, but maybe not a very enthusiastic member of consumer culture. Bigger wasn’t better. I was accumulating experiences, not things. And I was part of those scenes, those cultures. It was a way of encountering new ideas. Today it’s challenging for me to find something that feels new in experimental film. To a certain degree it’s also true in rock music as well. But age is pretty significant in terms of the question of expectation. So I can’t just blame the culture, I’m part of the problem as well!

Mike: I’m thinking of two essays, one written by Jim Hoberman in the Voice (“Avant to Live: Fear and Trembling at the Whitney Biennal”) and Fred Camper (“The End of Avant-Garde Film”) in the Millennium Film Journal. Both announce the end of avant-garde cinema. Hoberman: “The French call adolescence the age of film-going, and it may be that the movies you discover then set your taste forever. Certainly, my own life was altered in 1965, when I began frequenting a cruddy storefront on St. Marks Place and the even weirder basement of a midtown skyscraper. I knew movie-movies but this was another world: oceanic superimpositions and crazy editing rhythms, films made from bits of newsreel and Top 40 songs, ‘plots’ ranging from the creation of the universe to the sins of the fleshapoids, real people (often naked) cavorting in mock Arabian palaces and outer borough garbage dumps….” Both Hoberman and Camper detail the exhaustion of this adolescent moment of discovery, they’re middle aged now, and have seen it all. What else can you show me? What they both describe are not only alternative movies, but the alternative spaces those movies reside in. Sexuality arrives in their real lives just as undreamt possibilities unfold onscreen.

Kathleen: It’s interesting to think about the erotic space that was occupied by experimental film, the questions it raised about the body and sexuality. Today pornography is readily accessible, young people will have seen more explicit porn online by the time they’re fourteen than any experimental film could possibly deliver. When I was growing up it required quite an effort to access porn movies. You’d have had to visit one of several theatres on Yonge Street, which I did but not as a habit. When I was starting to look at experimental film it was a highly eroticized cultural space. That was one of its attractions.

Mike: Did porn kill the avant-garde?

Kathleen: Can the avant-garde be a lifetime passion? I don’t know. I feel that for me experimental music and film have been about experiencing thresholds. Once you’ve experienced that threshold and revisited it once or twice, it reframes your experience. What it does after that doesn’t carry the same thrill. There are practices using silence in music or abstraction in film that were provocative and exciting to encounter, but for me it’s not possible to maintain the same relationship to those formal gestures. I find those transformative moments in other kinds of practices, and I don’t think I’m alone in this… History is somewhere else, cultural practice has moved on. Today Harmony Korine is the Funnel. Spring Breakers is the new frontier. There are artists like Harmony who are doing things that may not exist within the same framework that gave rise to the avant-garde, but I suspect they are having a similar impact.

Mike: You stopped going to the Funnel.

Kathleen: When the Funnel’s venue on King Street shut down there was a big time lag between that closing and the new venue starting up. I lost the habit. I went to the new theatre on Soho once and didn’t enjoy myself there. I didn’t like the environment for some reason, I have no idea why I’m saying that. It’s partly about the changes I had already made. I was in graduate school at York. I was writing a lot, and going to galleries a lot more.

The Power Plant opened around that time, Ydessa started her foundation, Mercer Union was programming film in the project room. Film practices migrated to the gallery, and the Images Festival started up. There were an increasing number of festivals in Toronto, and that became the context in which I continued to view experimental and independent film.

Mike: What about the sense of a scene?

Kathleen: I didn’t feel I needed it anymore. I was newly aligned with the academy, not that I’ve ever figured out how to properly fit in there. I stopped making music, but I was still seeing bands, and my focus changed to visual arts and writing. The next time I became involved in the film scene was when the Euclid Theatre opened. That felt like another cultural moment with a new generation of people. For a while I went to the Euclid a couple of nights a week and it became a bit of a scene. Then I got involved with Inside Out and began programming films and video myself. Just a few years earlier the Funnel was the only place dedicated to avant-garde film. It’s amazing to think about how film culture has evolved in Toronto. By the mid-nineties what started as underground film culture had begun to seep into every university, art gallery and festival in the city. And then came the internet and all that has brought us…

Mike: So many of my friends have become parents, it makes me wonder if everyone has kids except for the people I used to know at the Funnel. Returning to Dot’s idea of a modernist utopia project that creates an alternative world, was saying no to kids a necessary part of this avant-garde moment? Anna Gronau (film artist and former Funnel director) recalled feminist discussions which figured domesticity as imprisonment. Kids were part of a paradigm that needed to be left behind.

Kathleen: Yeah, I think my assumption was that the family was an obsolete format for developing the self or transforming the world. I never really had any sense of myself becoming a mother. A couple of times I wondered, but only very briefly. I was happy to be an aunt. I think the rejection of motherhood and domesticity was fairly common amongst the women I knew. Kids weren’t really in the picture.

Becoming part of a utopian community and creating an alternative lifestyle involved constant critique: how you earned your money, what values informed your relationships, gender, sexuality, ownership, consumption…everything. Analysis wasn’t a special occasion activity. Living a life of creativity and transforming the world were pretty involving. Was there time, space or energy left over to raise kids as well? I think for a lot of people it didn’t seem so. I wonder if today it has reversed, if women see motherhood as a way of trying to transform the world? Parenting no longer seems like an obstacle but might even seem like the only conceivable path…