John Kneller: The Church of Film (an interview) (2001)

Kneller’s work is a compendium of documentary practice and lush, multiphonic landscapes which appear often as figments of the imagination — abstracts which flicker between the lines of reason and wonder, finally conjuring both. But while his ongoing gathering of images leavens an eye learned in the ecstasy of uncovering, these pictures are typically rephotographed in order to heighten their expressive potential, adding grain and supersaturated colour or layers of other pictures to re-invoke the magic of a world never seen before. Shot in marginal or neglected formats (standard and super-8), Kneller’s films remained for years a persistent rumour, occasionally surfacing in open screenings or group shows. When pressed, he would usually insist that none of his work was really finished, that it existed in a myriad of variations, of test rolls and material possibilities which had not yet been exhausted. Through the years Kneller would return over and over to the same footage, resequencing it, adding more complex layers of matte work and superimposition via rephotography, eventually producing a body of work, like Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, where each piece seems part of an organic whole — where the borders between one title and the next seem blurred and indistinct, where the material of the film is aging along with its maker, changing as his eye changes. This flowering of possibilities has been undertaken with an exacting technical precision and boundless patience, producing an exquisitely hand-crafted corpus like no other in Canadian cinema.

JK: It’s funny, people will wait at a bus stop or laundromat, but can’t sit through a five-minute experimental film. Sometimes they get so angry. People take their movies very personally; they know what they like, which is what’s been sold to them. A few years ago, I had to stop watching big movies. I just got tired of the way emotions are manipulated. Tears are welling up, there’s a big lump in your throat, and you can’t help thinking that all over the world folks you’ve never met are feeling just the same. I grew up in a small town of 5,000 people and just one movie theatre, the Royal Theatre in Hudson, Quebec. The Royal turned into a sports outlet and now, of course, it’s a video store. It’s all changed. I remember many a summer afternoon matinee and the way the sun would scorch your eyeballs as you left the theatre. In our small town the Royal was something that kept people together. For parents, it was a chance to get the kids out of the house for a couple of hours.

MH: The communal babysitter.

JK: It reminds me of this guy who used to have small booths with super-8 cartoon loops. The show would last a couple of minutes and cost a dollar and he kept it running into the late eighties. Parents would send their kids in there with ten bucks just to get rid of them for a while. Now he’s switched to videotape.

MH: When did you start making movies?

JK: When I was fourteen my friend got a super-8 camera and we made little films with kids in the neighbourhood. Everyone came to see them when they were finished. A few years later my parents worried about my going to the local high school, so they sent me to a boys’ private school for three years, between 1980 and 83. At the time it seemed like the worst thing; having to wear the uniforms and being so anxious about girlfriends, sex in general. But now I think it was a good thing — I might have got stuck in a rut back in Hudson. In CEGEP I enrolled in commerce because my parents didn’t see much of a future in film. That’s where I saw my first Brakhage and Anger films. Afterwards, I applied to the Concordia University for film but didn’t make it. I still have dreams about that interview and have spoken with other filmmakers who remember the terror of applying. I’d been going to movie nights run by a punk and when I told them what movies I was seeing they figured I wasn’t for them. I think the interest was there, but in a small town you’re limited in what you can see. You’ll find Faces of Death but not Dog Star Man in your video store. I’d planned on staying in Montreal, but got accepted at the University of Toronto, and I’ve been here ever since.

MH: You made films at university?

JK: That’s when I really got going, though it was frowned upon; we were told there were too many filmmakers out there already. The university program is strictly film history, criticism, and theory, so I started to experiment with super-8 on my own time. I used to go to all the Innis Film Screenings and that’s where I really saw experimental films. As soon as I saw those films I knew this was for me. It was a much more purist approach to film, unconcerned with demographics or test screenings. It was film for film. I loved Pat O’Neill’s work, Paul Sharits, Michael Snow, all that structuralist work, Joyce Wieland. I admired what people were doing in the sixties. There were different approaches to lifestyles, and, as a result, different approaches to filmmaking; you sensed the changes in their world. I saw some films that were optically printed and felt that’s what I wanted to make, to use the printer to express a feeling or an idea, not to use it for standard movie-magic special effects. To fool people. That’s when I made those three “S” films: Spring (4 min 1991), Shimmer (4 min 1988), and Speck (4.5 min 1989). I knew a lab guy who could put together three rolls of super-8, and I became fascinated with multiple exposures, marrying the images in the printing. I was doing a lot of time-lapse work shooting clouds and landscapes, which is what I’m still shooting now — a lot of the seeds were planted pretty early on. Especially this fascination with water. If you’re printing with low-quality systems, water seems to hold its image quality longer than other kinds of images, it stays extra sharp on film. I was also fascinated with the feedback you can get through a reflex viewfinder on a super-8 camera if you look right into the sun. I’d set the frame up with the sun in the corner looking out a window, with the light spraying across the frame. You get your eye wet, and if you press your eyeball right up against the glass in the viewfinder, the light comes into the finder, bounces off your eye and runs back onto the film. That particular effect is evident in parts of Speck and definitively in Picture Start (3 min silent 1985–90). The eyeball is magnified tremendously and luminous white eyelashes flutter about the focal plane. For a long time I was trying to perfect that. When I shoot I’m probably overly meticulous, spending too much time setting up, but I enjoy working that way, making every shot count.

MH: Were you shooting in a gathering mode as opposed to following a script?

JK: Absolutely. I still get the urge and decide I have to go out today and film something. Though I don’t feel comfortable shooting strangers — filmers have a responsibility to not just take take take. It’s amazing what’s changed in ten years. Everything but me. I’m still doing exactly what I was doing then, I’m just a little better at it. I still go about filmmaking as a major part of my daily life. In the late eighties I had an apartment down in Kensington Market which I set up as a little studio. I had a couple of super-8 cameras and a projector with a flip mirror so you could project on the screen. I had also been experimenting with slow-burning film frames and all kinds of crazy set-ups for multiple projection rephotography. I was interested in reflections of light patterns on various hand-held gels. I made experiments using single-frame rephotography. Some very crude methods were used, including filming from an editor/viewer screen. All of these limited techniques found their way into the three-part superimposition film Speck. Spring’s a bit different, though. I went into an old abandoned building and put it all together in my head before starting to shoot. There was a presence there. It was a place for the homeless, full of shit and pornography and glue bottles. I was pretty naive then; it hadn’t occurred to me that people would ever have to live like that. At the same time there was a certain fascination because I imagined a life where you’re not tied to anything, you’re free. The last shot of the film shows an oval window which the camera moves toward, suggesting freedom — and its costs. Most opt for more regimented forms of freedom.

Toronto Summit (6.5 min 1988) is a document of the Toronto Summit rally and march. I’d become involved in the local activist scene, though I was reluctant to accept its easy equation of the personal and political. I had a friend who couldn’t separate the two at all — whatever he felt that day was the reigning politic. Artists are guilty of this, too; you have to let things go in order to do the work, you have to be selfish to get it done, but it can create problems with your relationships. It takes a toll. The G7 is a meeting of world leaders from seven countries, including Canada, and it was our turn to host. The leaders huddled at the Convention Centre, which was surrounded by a giant wall with helicopters circling night and day. We were going to march from the legislature to the walls and tear them down, or at least bring attention to this barrier between the elite and regular schmoes like us. It was my first taste of a big city rally. It all took about three hours, with singing and speeches and then a march. There were cops in riot gear and a sit-down protest. Anyone who tried to climb the barriers got arrested, and mostly it was very reserved. But with that many people it could quickly become dangerous. A newspaper box was burned and people danced around it, while endless rows of cops looked on. I could hardly imagine it was Toronto, it looked like something out of a war zone. That’s when I saw how fragile democracy was. There was a line, and I wondered at what point the cops would take out their truncheons and start beating people. It was a scary time to be living. No one talks about it any more, but I’d grown up with the imminent threat of nuclear war. My teachers would pray that no crazy someone would take office and press the button. That was the fear. We knew there was nothing like a limited-scale nuclear war. It meant the end of everything.

In 1986 I lived in residence, which was very new for a guy coming from a small town. Steve Lerner lived next door and we got along like brothers; both of us were away from home for the first time. But to get anything out of the guy was murder. I had this little film I was working on and wanted to shoot in his room, but before he said yes I had to type essays and run errands, it was driving me nuts. He had a bunch of regular-8 home movies from his family and I had a projector. Every once in a while he’d have a hot date and, as one of his ploys, he’d borrow my movie projector and show his home movies. I was jealous because I wasn’t getting any action at all, it was terrible, years went by. But things were going well for him because of these movies, and finally he showed them to me. He said there was something strange, there was something wrong with one of them. He put it on and it blew me away. It’s a very simple home movie showing a baby being washed, playing, rocking, being held by his parents. A very basic home movie with in-camera cutting. But something happened during processing — the emulsion’s not entirely there, it’s peeled off and folded back, leaving lateral excisions. The overall effect is that this banal home movie has a beautiful new life given to it by the material nature of the film. That became Traces, Fragments (4 min 1986). I don’t really consider it my film, I just found it. I bothered Steve for years about it, and in the end he acquiesced, knowing I was serious, that I was committed to this kind of filmmaking. I had ideas about turning it into a multi-screen extravaganza. In the clear areas of the image I wanted to show fragments from sixties newsreels — moonshots, the JFK assassination, the King assassination — along with scenes from the baby’s later life. I tried to do all this on a contact printer at home on regular-8, but never achieved it. Kika Thorne was always urging me to show the original, insisting it was beautiful the way it was. In the end I realized she was right. For two years I made prints from the original and tried to rework it but finally had to stop. Through the years I’ve assembled all my films on large reels, but then I start optical printing and they all get broken down again. It’s like an endless expansion and contraction, never being able to decide what I want to do with this stuff. It’s always been process first. From 1992 to 95 I worked intensely on the printer and pilfered materials from past work to make new things. I had the idea that Speck could benefit from a complete reworking given the new possibilities of the optical printer. As was the case with Traces, Fragments, this endless reworking of old originals did not prove entirely fruitful. So, I’ve finally decided (the hard way), to remaster all of the older superimposition films from the original super-8 A-B-C rolls exactly as originally intended.

MH: It’s amazing to me that you work so hard, and for so long, with such exacting precision, on a single film, often poring over it frame by frame, with many layers of superimposition added, and when you get close to finishing something, you just abandon it and move on to something else.

JK: Honestly, I think I have to get away from that after going through this massive editing project trying to make some sense of it all. For the first time I’m going back and deciding what’s a film and what isn’t, and having proper prints made.

MH: Tell me about your leaf obsession.

JK: Every fall between 1990 and 1993 I’d go out and shoot leaves. It would take me a month to shoot seven seconds because every shot was set up like a still photo. I remember Robert Breer doing frameby- frame work in Fist Fight, using a different image for each frame. It had a fascinating kinetic effect on the screen, unlike anything I’d ever seen before. That shooting was the beginning of Architectures and Landscape Compilation June 1994 (14 min silent 1993). I’d also been photographing a lot of water images which I processed by hand. Every day I woke up at seven and did a day’s worth of processing. This went on for five months and the results were lousy — it was all very flat, lacking contrast. I thought maybe it needed more agitation, but then there were areas of oxidation and brown spots on the film. I cut out all the brown sections and the remainder became the backing matte for the colour leaves. They were run together in the optical printer, and that became a pretty important part of the film. It was my signature style for a while. I’d also collected all this regular-8 footage from garage sales. You shoot one side of the roll, then take the film out of the camera, turn it around, and shoot the other side. Usually when it’s processed, they slit the film in half and give it back to you. But if it’s not slit it can be cut directly into 16mm footage, producing a four-screen effect. It was all Kodachrome, so the colour was beautiful and saturated. This was incorporated with the water/ leaves and some stained glass windows I shot. The windows are something made by humans which try to imitate the beauty of nature, to evoke those translucent, saturated colours. The film compares these two moments and reflects on its own making, its own evocation of colour. There’s a shot of Hitler in the film and some said I should take it out, but it’s followed by these pixilated flowers I shot slowed down on the printer, red against a black background, which have a very somber quality, the idea being that there’s beauty but such horror as well. Working in black and white has never been of great interest to me. Black and white’s in vogue now but even mainstream audiences don’t always like it. It’s funny, I remember this guy who made a beautiful video for the New Country Network TV station. After it aired, people called in saying, “Look, I just bought this big colour TV and no way in hell do I want to watch black and white videos.”

MH: Do you worry about your audiences? Is there enough of an audience for your work?

JK: In 1990 I got a call from Pleasure Dome [an artists’ film/video exhibition group in Toronto]. They asked if I wanted to show and I said, “I’m surprised you’re calling me, I’m really just getting started, I’m honoured.” And they said, “Well, actually, we wanted someone else but they cancelled.” [laughs] But I think Pleasure Dome does a good job and has been supportive of my work. At the Innis Film Society, attendance became so bad it was embarrassing. I remember the Ernie Gehr show where six people came. You start wondering, “Why am I putting all this time into the work?” A show’s never lousy though. Even if there’s just one person out there, there’s something happening. A good film is when you bring home images, when something sticks.

MH: Is there something political about making a film that has no use value?

JK: After Agnes Varda watched a program of Kenneth Anger’s work she said, “Well, that seems like a pretty easy way to make a film.” People think experimental filmmakers have it easy because of the freedom, but it presents a different set of challenges. I’ve always wanted to work on a film at my own speed. In my own way. I’d get the films so close to being finished that I’d lose interest because the challenge was no longer there, I’d learned everything I wanted to from that particular film. Then I’d move on to the next thing. Because I was so eager and excited to understand film, a lot of the early work was left in disarray. I was scared of the big film labs, because I’ve always done everything myself, made all of my own prints. People are amazed that I’m able to keep going on my own terms. They imagine there’s only so long you can be a film or jazz martyr, someone who plays just for the love of it. But it’s more important for me to make films than have a comfortable living. I have a day job so I can keep going. I made Architectures and Landscape Compilation in 1993, revised it a year later, then kept working on it until it became We Are Experiencing Technical Difficulties. Regular Programming Will Resume Momentarily. (16 min 1996). It also shows an intersection of landscapes and architectures with humanity in between. But it uses more travelling mattes and images within images, and offers a different treatment of colour. I used a lot of high-contrast self-processed water imagery, which was rephotographed using alternating colour filters with a slide projector as the light source. This produces a flickering colour field against the high-contrast photography. The stained-glass windows return, but while they’re shown in their pristine original in the background the foreground shows the same windows with fifteen added. It’s like an endless expansion and contraction, never being able to decide what I want to do with this stuff. It’s always been process first. layers of superimposition. I used my projector to run into the printer so the images are very quick, fifty times faster than normal. This contrast between the two kinds of windows suggests that as much as religion strives for the best in human experience, it’s also responsible for the boys in Mount Cashel or going to war. We’re in such a high-tech age but in other ways we’re completely backwards. Experimental film is the way and the truth. I do believe that. It has such freedom because you’re not catering to a market, you’re interested in ideas. But why make these films? Everyone who sticks with it is miserable, or they go crazy or shoot themselves. A lot of people show promise and stop. I saw a student film that was fantastic but now this filmmaker installs car antennas for a living. But I think there’s a way. When I first saw Dog Star Man I was eighteen and very open and impressed, but as soon as people hit their twenties they just head for the dollars and leave these films behind. They’re missing out on something great. I guess I’m a bit of a purist. I don’t even work with a Steenbeck, I always work on a bench. People say, oh, that’s so archaic, but I find it useful. When you’re winding the film back you’re thinking of whether your decision is going to work or not. Just because you can edit fast doesn’t make you a good cutter. One thing about working on a printer is that you’re actually exposing film to light, and as soon as you start taking film into the digital domain, you’re getting further away from it being light and turning it into information instead. I still love the quality of projected light. And there’s something to be said about taking time over things. I just prefer working that way. If that makes me a dinosaur, well …

John Kneller Filmography

Traces, Fragments 4 min 1986

Shimmer 4 min 1988

Toronto Summit 6.5 min 1988

Speck 4.5 min 1989

Picture Start 3 min silent 1985-90

Spring 4 min 1991

Tier Film 6.5 min 1991

Holiday Tattoo 1.5 min silent 1992

Architectures and Landscape Compilation June 1994 14 min silent 1993

Architectures and Landscape Compilation Dec 1994 6 min silent 1994

Drop In/Shoot/Drop Out

version 1 2.5 min super-8 silent 1995

version 2 8 min super-8 silent 1995

Circle Takes 5 min 1992-95

You Take the High Road 6 min silent 1995

We Are Experiencing Technical Difficulties.

Regular Programming Will Resume Momentarily. 16 min 1996

Separation Anxieties 9 min regular-8 1998

Sight Under Construction 35 min 2001

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Moving In Light: The Films of John Kneller

As multinational capital continues its relentless conversion of experience into currency, figuring even our sexual practices, our emotional convergences, our unspoken longings as sites of display, exchange and finally commodification, there exists alongside the minor protest of avant-garde cinema. We might deem it minor because it seeks none of the trappings generally associated with success or visibility or career. There is no place where one might arrive, no sinecured perch of retirement, no likely prospect even that a lifetime’s work will not turn to dust as its material base gives way to the ravages of time. It’s ‘protest’ lies precisely in its refusal, in its insistence on circulating in the unwatched backwaters of the metropolis. Here small movements of emulsion are passed by hand from one maker to the next, or hosted in living room screenings – possible utopias, new worlds.

This tradition of dissent finds its origins in the late eighteenth century, when industrialization shattered the traditional communities of church and village and occasioned massive social upheaval. In the face of the machine, poets turned inward, celebrating a newly individual consciousness, pitting the resources of the imagination against the designs of capital. Using the natural world as a metaphor for alternative sign systems and privileging the sense of sight above all others, their art would declaim a radical subjectivity. Today, there remain remnants of this faith in the shrinking universe of fringe film, cine-poets whose encounter with the natural world is given over to a lyric vision which owes much to a rigorous adherence to materials. Of their number, few have been as resolute in his careful reworkings, nor as casual in his refusal of public exhibition, as Toronto filmmaker John Kneller.

Kneller’s work is a compendium of documentary practice and lush, multiphonic landscapes which appear often as figments of the imagination – abstracts which flicker between the lines of reason and wonder, finally conjuring both. But while his ongoing gathering of images (often in standard or super-8) leavens an eye learned in the ecstacy of uncovering, these pictures are typically re-photographed in order to heighten their expressive potential, adding grain and super-saturated colour, or layers of other images, to re-invoke the magic of envisioning a world never seen before.

His first film, appropriately dubbed Traces, Fragments (4 minutes regular-8, 1986), is made of found footage. Kneller worked for years in Toronto’s only super-8 lab, and these rolls were considered waste because of irreversible problems during processing. Befitting a maker’s first work, this film narrates moments of childhood. These home movies show a child playing in the bath, exploring a universe of toys. These early moments summoning the site of home as the place of reproduction. But, as always in Kneller’s work, the impact of the material is strongly felt, and here it is the emulsion itself which acts as a counterpoint to the pictured activities. Crammed with gelatin deposits and a cracked surface, it struggles to transmit these memories. Its material transport attempts to reproduce impressions which seem to emanate from the child, instead of the filmer, giving us the unmistakable viewpoint of an untutored eye whose vision threatens to crack the confines of his domestic surround.

Two years later he produced Shimmer (4 minutes super-8 1988), a poetic brief which already demonstrates Kneller’s characteristic image manipulation, lyric sensibility and insistence on a simultaneous presentation. The central figure of this film poem is a distorting mirror, reflecting from a distance the stern grid of an apartment block, rendered now in wavy lines of loopy abstractions. This conversion of material into immaterial, from normative representation to an abstract counterpart, uncovers a new and subterranean order. This conversion is emblematized early in the film when Kneller shoots an interior scene dominated by a window, its glassy outlook providing a frame in which the outside may be re-imagined as part of an interior space, as a kind of moving picture. Kneller then manipulates the entire frame, causing it to ripple, insisting that each vantage is similarly mediated and contingent. He follows with an image of a bottle, whose emptied glass container provides both a metaphor for the camera and for vision itself. A montage of the natural world ensues, time lapse clouds are superimposed with water which has been re-photographed through filters to lend it a fiery look, joining these two opposing elements. The filmmaker himself re-appears at the window, adjusting glass, a gesture which serves to host an onrush of new mirrored distortions. These finally become a kind of ground against which further abstractions of light flare, and out-of-focus shimmerings, play. It closes with an image of a plant by a window, as if these cycles of transformation had emerged from a plant’s vision after all, its conversion of sunlight into oxygen (photosynthesis) an emblem for the transformative power of seeing.

For his next project Kneller would turn his visionary poetics to a more sobering subject. Each year leaders of the seven (self-proclaimed) ‘leading industrial nations’ gather to speak of issues of mutual concern, and in 1987 this convening took place in Toronto. Toronto Summit (6.5 minutes 1988) is an inner city portrait which shows a metropolis battened down for possible conflict – its streets closed and cordoned while helicopters circle overhead in perpetual surveillance. This materialist documentary pits street activists against the phalanxes of police which have arrived to ensure the safety of the summit participants. How quickly they turn the city into a grimly armed fortress. As the film proceeds through dialectical montage the two sides gather, the black shirts from windowed enclaves, and the protesters who gather to sing, dance and make speeches. Finally open conflict breaks out, as the barricades fall and both sides clash in order to lay claim again to streets too easily ceded to global oligarchy.

Speck (4.5 minutes 1989) is an ‘abstract’ drawn from nature, its close-ups of softly ebbing blues and greens cast in a serial rhythm. This pastoral sublime reawakens the hidden corners of the eye, using the most representational of mediums to document a world of colour, leaves and playground light in order to suggest an order that lies in wait beneath a vision ruled by language. While its convening is entirely without the representational tropes that signal a documentary consciousness, the weave of its ordering, its unrelenting attention to detail and the ephemeral shimmer of all that passes before the camera’s gaze, suggests that these visions lay in wait for all who have an eye to see them.

Picture Start (3 minutes silent 16mm 1985-90) is another meditation on the natural world, its carefully wrought superimpositions of sky, leaves and chromatic close-ups a powerfully felt evocation of an animistic surround. Photographed with a keen eye for detail, Kneller’s painterly overlays collage these moments into a gently flowing homage to the present.

Spring (4 minutes super-8 1991) is a brightly hued cine-poem, a walk through the natural world, its slowly gathered rounds of superimposition conjuring a season of renewal and re-awakening. It opens with reflections in water, demonstrating both film’s ability to reflect its surround and to change it. Time lapsed clouds follow, with the filmer’s face set inside them, as if they were raging inside, or that the fury of his impressions were enough to remove any distance between Kneller and his environment. Flickering buildings ensue, a wondrous light in windows, a pulsing search light, before the Kneller’s shadow walks across a sun drenched floor. A series of rainy scenes follow, though they are remarkably sunlit, somehow it is both rainy and sunny at the same time. This paradox leads to a paradoxical geometry – tall buildings glimpsed in a distorting mirror, which them into softly ebbing shapes. We see a face inside clouds and then fire superimposed and then fireworks, the whole building like rounds in a fugue before being released in the film’s final image, a walk towards a hole which admits a view of the city. This aperture admits by excluding, offering an image of subjective sight.

Tier Film (6.5 minutes super-8 1991) is a street documentary strained through metaphors drawn from the natural world. It is a portrait of a street preacher, and the inflamed tempers he provokes as he holds forth in Toronto’s downtown core. Kneller begins, as usual, with an abstract display of light itself, a phantasmagoria of lens flares flickering in a multi-hued cacophony. This opening serves both to underscore the film’s subject as an image, as well as giving way to the light/plant metaphors which accompany the preacher throughout. Passing vantages from a car window follow, tinted pink and blue. An abstracted face glimpsed in close-up prefigures the preacher’s appearance before we see an image of flowers – then two children walk down a laneway garlanded with the shadows of potted trees. After brief shots of a stained glass window and another street shot with a floral display occupying the foreground, Kneller delivers us to the film’s central motif. The preacher appears surrounded by a circle of listeners, his voice slowed and distorted. “I am the messiah of the world.” He is challenged by a thirtysomething woman who pushes him back into the crowd. Their interactions continue throughout, the preacher passively waiting for her to finish while she grows ever more agitated in her interventions, grabbing his collar, shouting and shoving. These scenes are all over-exposed, as if his messianic longings had granted him a gift of light. The soundtrack switches from his low toned proclamations to an out jazz track as she continues to accost him. The track falls silent as his re-photographed image recurs, this time in protracted meditation. He is seen from an extreme side-long angle, stretching his face across the screen of re-photography. Here Kneller offers his own intervention amidst the speech of the divine, straining to catch ‘another side,’ the now silent track offering a dialectic of speech versus silence, man versus woman, the annointed versus the herd. The film closes with a montage of single framed flowers, their insistent presence throughout the film – forever potted, bound together in bouquets, or assembled in street displays – demonstrating the impulse to contain, mediate and control nature. The preacher’s relation to his god is similar, bending his calling into a self-obsessed rant which refuses the world around him. Kneller’s gentle montage resists this singularity, pitting via montage one view in relation to another, each figure contingent on the appearance of the next.

Originally photographed in regular-8, Holiday Tattoo‘s (1.5 minutes 16mm 1992) delirious compendium of travelogue sightings are gathered together in this four-screen version. Begun with a church’s stained glass layered over water and trees, Kneller suggests that these divine apertures are already removed from their origins in nature, and so make possible the onrush of spectacle the rest of the film conjures: urban neon signage, fireworks, a bridge parade, planes flying overhead. Moments of family appear throughout, gathering round a car, and waving from wheat fields, the innocent frolic of their life together marked by this storm of the public sphere which rages all around them.

Drop In/Shoot/Drop Out (2 versions: 2.5 minutes super-8 silent 1995, 8 minutes super-8 silent 1995) features a four-screen display, all re-photographed onto super-8. It is a summary work, featuring protracted excerpts from many of the filmer’s past efforts. As a result, it is exceedingly dense, each of its four screens often further dividing itself into further sub-screens, with complex matte work providing images of rapid transformations in the natural world. Fireworks, night time neon signs and television excerpts appear simultaneously alongside Kneller’s characteristic single frame pyrotechnics which conjure autumnal forests. This juxtaposition insists that we have become a repository for a vast storehouse of images, and have turned to understanding the world in just the same way, as a fleeting visual spasm, a spectacle of sight.

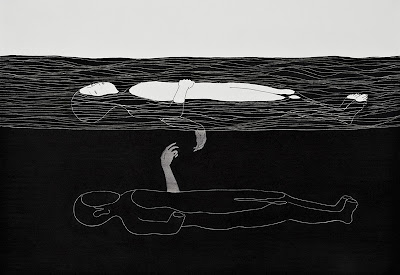

Circle Takes (5 minutes 1992-95) is an animistic mystery gathered round a central, circular motif. While the film is largely abstract, it manages nonetheless to evoke a palpable sense of awe in the face of an eruptive, dangerous ‘natural’ world. It opens with a matted rectangular image showing light cast in a circle over water, superimposed with a bluish concrete structure. Together, they appear as shifting tectonic plates, creating a simultaneous sense of wonder and unease. The second ‘scene’ features the central image of the film – taking a fragment of found footage, Kneller burns a hole through it a frame at a time, creating a bubbling, cracked emulsion which a series of climbers slowly make their way through. This scene gives way to a three-screen display, one showing distorted buildings, another a light cast on a circular object, the last an image of light itself, a lens-flared and prismatic close-up. Kneller then returns to the climbers, the whole frame shaking, the emulsion cascading in multi-hued circular bubbles. A final variation shows them walking backwards in negative before the film’s final image(s) – a cacophony of superimpositions which show a moon in water, light cascading off its circular girth, with red tinted water slowly curling round it. Painstakingly re-photographed a frame at a time from super-8 to super-8, this evocation of natural disaster via the shuddering mechanism of the projector reverses the usual relation of figure and ground. Here, it is the earth which is the primary ‘character,’ while the humans appear as dimunitive figures climbing towards an unknown destiny.

For years Kneller entered autumnal treelines and photographed, often a frame at a time, evoking an ecstatic communion of colour and seeing. Carefully re-working his original material using a complex series of mattes and superimpositions, he assembled this material in three works: Architectures and Landscapes Compilation June 1994 (14 minutes 1994), Architectures and Landscapes Compilation Dec. 1994 (6 minutes 1994) and You Take the High Road (6 minutes silent 1995). Architectures and Landscape Compilation Dec. 1994 (6 minutes 1993) is a notebook of sorts, a collection of optical printer sketches and single frame photography.

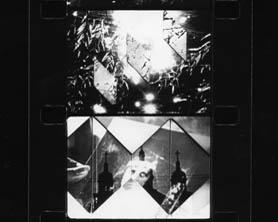

Two years later, both of Kneller’s notebook compilations have both been re-focussed and augmented in a virtuosic display of re-photography and densely layered images re-named We Are Experiencing Technical Difficulties. Regular Programming Will Resume Momentarily. (16 minutes silent 16mm 1996). Framed by images gathered while floating through a creek, a small matte appearing in the midst of the water lending a vantage of the treelines to come, a protracted 3.5 minute meditation on water ensues, its high contrast contours turning this display into a moving abstract expressionist canvas. The second movement shows trees in autumn, the brilliance of their colours often overlaid with pans over stained glass windows, the brilliantly coloured Kodachrome lending the whole a flickering ecstatic feeling. The third movement shows a woman slowly opening a letter and pulling out old photographs. Diamond shaped mattes cut across the frame as she lifts them from their long buried container. One is labelled ‘MSA Films,’ while others show portraits of folks long dead, so these archives allow these faces to look out once more into a world where they’ve become only a distant memory. This nostalgic requiem gives way to another sequence of leaves, slowed again through re-photography and glimpsed through window mattes. This natural sojourn is filled with the wonder of colour, of a re-awakening of those returning to the world after a long retreat. The leaves turn again to black and white, processed by hand and sabbatiered, turning their white ground into grey, the swollen flickering emulsion making of these wind blown fragments a body which swells and contracts. A final three minute recapitulation ensues as Kneller tilts down the forest in real time, matching this gesture with another pan of a large building tinted blue. A woman appears, her face smothered with fantastically tinted leaves, before they turn again to black and white. The film closes as it began, with a meditative float down a watery transport, implying that the sights between have all been glimpsed in this single trip.

Continuing to work in marginal or neglected formats (standard and super-8), Kneller’s work remained for years a persistent rumour, occasionally surfacing in open screenings or group shows. When pressed he usually insisted that none of his work was really finished, that it existed in a myriad of variations, of test rolls and material possibilities which had not yet been exhausted. Over the years Kneller would return over and over to the same footage, re-sequencing it, adding ever more complex layers of matte work and superimposition via re-photography, eventually producing a body of work, like Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, where each film seems part of an organic whole. Where the borders between one entitlement and the next seems blurred and indistinct, where the material of the film is aging along with its maker, changing as his eye changes. This flowering of possibilities has been undertaken with an exacting technical precision and boundless patience, producing an exquisitely hand-crafted corpus like no other in Canadian cinema.

Originally published in Cantrills Filmnotes, 1996.