As Far As We Could: an interview with Munro Ferguson (September 22, 2013)

Munro: John Porter did a performance called Scanning 1 (3 minutes 1981) which started when he shot the exterior of the Funnel building with a series of pans, and then in performance he picked up the super 8 projector and repeated his camera gestures, moving the projected image across the walls. He managed to sync up his movements well, it was obviously rehearsed. The image became a searchlight creating a window in the wall, or that was the illusion. It was such a nice use of simple analog technology and blew the minds of everyone who saw it. John’s performance epitomized the magical things that could happen with the simple materials we were using back then.

I remember walking into the Funnel gallery and seeing a beautiful painting by Sharon Cook. It hung there for a while and eventually I bought it, it was the first time I’d ever purchased a piece of art. The painting is called The End of Hercules at the Edge of the Grand Canyon. It’s a picture of a rabbit-like creature riding backwards on a donkey in the woods lit by two beams of carlight, with a fire in the distance. In the foreground there are two barely perceptible women watching the scene. Sharon assured me it’s her and a friend. It’s a hallucination in the neo-expressionist style of painting that was big in Toronto in the early eighties.

I really liked the spirit of the Funnel, it was cool. It supported traditional avant-garde film, with revolutionary/psychedelic influences from the late sixties and seventies, and there was a punk attitude layered on top that created something edgy, exciting and fun. I had a great time there.

Mike: What made the Funnel punk?

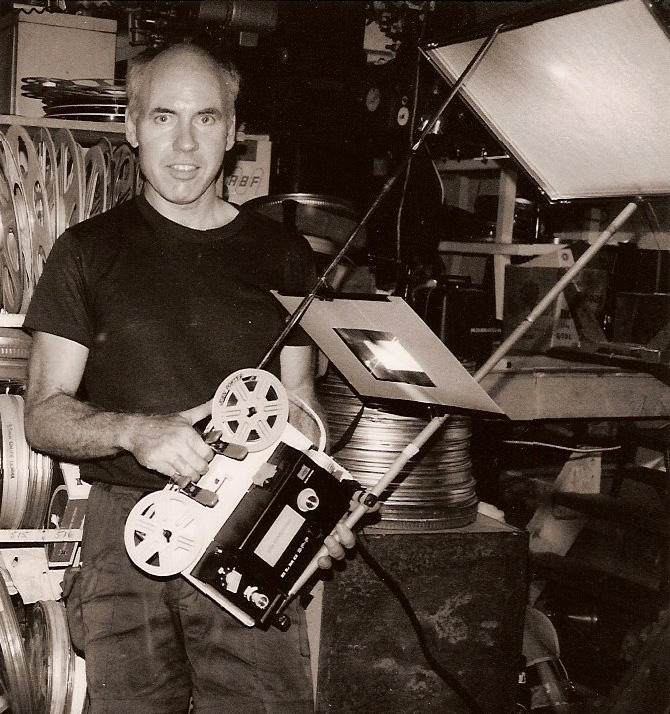

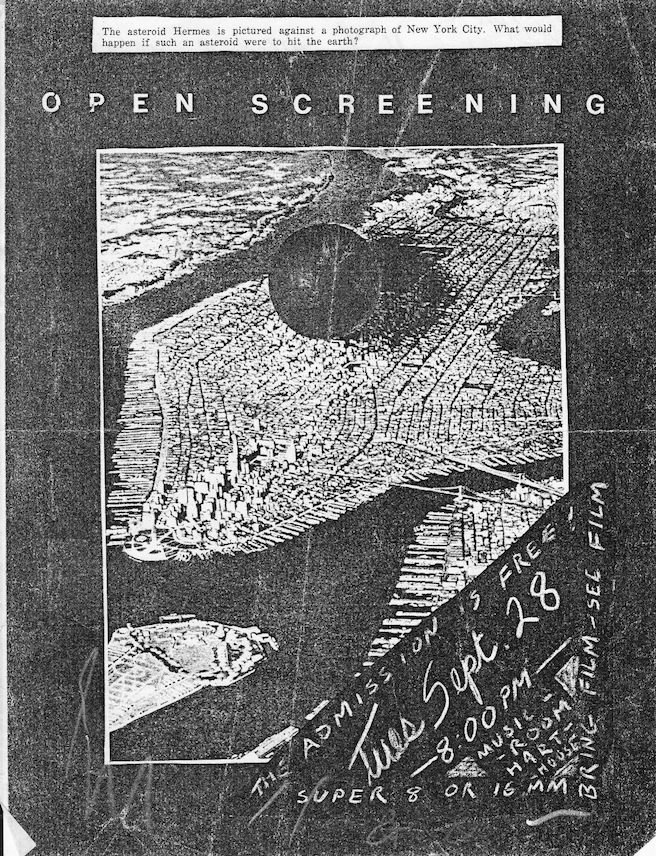

Munro: Obviously the posters. There was a rebelliousness, an irreverence, and humour in the films we saw and the people who were there. There was a feeling of cohesion in the group, everyone knew each other. I was introduced to the Funnel by David Bennell when I was a student at the University of Toronto studying philosophy. But I had been making experimental films since I was a kid, I made my first film When I Get Older (running time???, 1967) when I was seven.

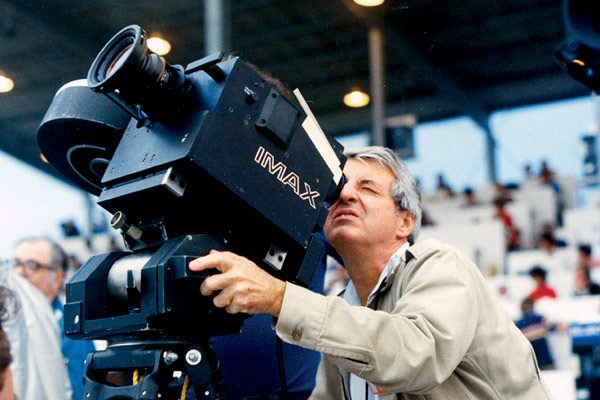

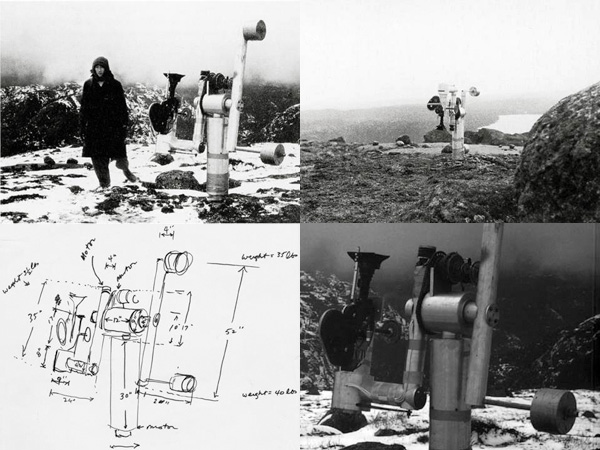

Graeme Ferguson is my father. He went to the University of Toronto and became head of the film society even though he was a political science major. The film club screened art house and avant-garde films. They invited Maya Deren to come to Toronto and show her work on November 6, 1950 at the Women’s Union Theatre. She was one of the first people to encourage my father to make films. Other members of the film society included Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland and they became friends. In the late 1950s he moved to New York and made verité documentaries including the academy-award nominated Rooftops (1960). Later, he was commissioned to make Polar Life, a multi-screen installation for Expo ’67, and we moved back to Canada where he co-invented IMAX.

When Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland moved to New York they stayed with us while they were looking for a place to live. I was about a year and a half old at this point, I was babbling away but the sound didn’t make any sense. Mike came up with this idea that I was the reincarnation of a Tibetan Lama. They would read the classified ads to me and ask which apartment they should get. “Does this loft sound good to you?” I would make a lot of noise and they would say, “Oh yes, very profound.” Apparently Mike would do things like pick up a spoon and say, “Fork, fork,” trying to teach me the wrong words for things. He was mischievous like that.

When I was a kid I would be taken to their film screenings. Joyce and Mike were people I knew really well. I would visit their loft and Joyce would take me to the Museum of Modern Art and show me paintings and talk about them even though I was seven years old. It was pretty amazing to get their perspectives on the world. I thought filmmaking meant you were supposed to hold the camera upside down. I thought comic books were art. I realize now that they had very unusual views but at the time it felt normal. I thought making experimental films was what everyone did. It’s certainly what I wanted to do. I saved up my ten cent a week allowance for a year so I could buy a super 8 camera. I didn’t want candy, I just wanted to make movies.

Joyce Wieland, Pierre Théberge (National Gallery director), Michael Snow, 1971

photo by Arnold Mathews

My mother Betty Ferguson made a handful of found footage films. The first was called Barbara’s Blindness (16 minutes 1965) and was done with Joyce Wieland. Joyce: “We started out with a dull film about a little girl named Mary and ended up with something that made us get crazy.” In the seventies she worked on three collage films: The Telephone Film (14 minutes 1972), Airplane Film (35 minutes 1973) and Kisses (55 minutes 1976). Kisses offered shots of kisses, Airplane featured only shots of planes. They are early motion picture catalogues. More recently Christian Marclay made a twenty-four hour found footage installation called The Clock (2010) which features a similar collection of clocks and watches.

My mom had an editing room in our New York apartment. She had rewinds, bins and a viewer. Joyce would come over and they would look at stuff on this cool projector that could slow and speed up footage. They’d laugh and laugh, it was great. When colour arrived, television stations in New York started throwing reels of black and white film into the garbage. My mom grew up during the depression and hated the idea of waste, so she would grab them. She still has racks and racks of them at home. She’d go through these films and find every shot with a telephone or an airplane or a kiss in it. I watched and loved them when I was a kid, they were very accessible for a child. I still enjoy showing them to people, even for viewers who don’t have much exposure to this kind of work. It’s not the most challenging experimental filmmaking, but it’s still structural film. She lived about an hour outside of Toronto on a farm where Joyce would come and visit us all the time. My mother would come in occasionally for a Funnel screening, and her films were screened there. Making films for my mother was play. It’s funny because she said this one thing to Mike Snow who likes to repeat it: “I make the rules and I break them.” That’s exactly what my mom was doing, and Mike certainly does that.

I was in Mike’s Rameau’s Nephew (1974) when I was eleven. I’m the smartass kid with the long hair in the airplane scene. I think I was in one of Joyce’s films, Bill’s Hat (1967). I knew a fair bit about experimental film, but it wasn’t until I met David Bennell at the Hart House Film Board that I connected with a community. There were no film production departments at the University of Toronto, but there’s a little filmmaking club called the Hart House Film Society. David Bennell was the technical director, basically taking care of some super 8 equipment, Bolexes, an Arriflex, some sound equipment and lights housed in a tiny little room. I started making films there when I was a student from 1979-83.

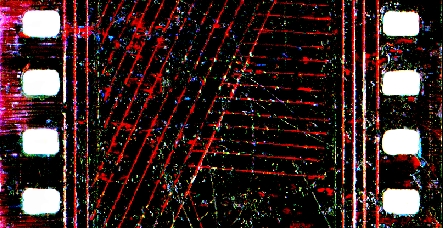

David encouraged me to come to the Funnel and by the second year of university I was a “core member.” I wasn’t involved in the construction of the theatre, I was entering a community of people who all knew each other really well. I was a little bit of an outsider but I loved the place. I remember Midi Onodera’s films, and of course Ross and Mikki Fontana. I remember Sharon Cook’s Evinrude Outboard (2 minutes 1982), which loops an outboard motor and the soundtrack was funny, I think she made the sound of a motor. Then there was David Bennell’s Hadrian’s Villa (12 minutes 1982) he shot on an Italian getaway in black and white and then treated with chemicals to get these really great colour effects. I liked materialist-based experimentation like Villem Teder’s chemistry experiments. There was a hypnotic quality to his work. I remember sitting through two long films by Mike: Rameau’s Nephew (4.5 hours 1974) and La Region Centrale (3 hours, 1971); both evoke unusual states of consciousness. I date that back to the sixties ideal of using film to create alternate states. Cinema was a social drug, part of the psychedelic moment.

The fight against the Censor Board was the big battle everybody was really upset about. I remember John Porter doing a performance where he screamed about the Board. There was a lot of anger. But in retrospect I realize it was great to have something to fight against. It energized the place. I came in and helped out a little with the 1981 renovations that the fire marshals demanded to bring the building up to code. David was very involved with the construction.

David’s a great guy, I loved him. He was handsome and charismatic, incredibly generous, warm and funny. A great chef. I still make a dish I call David’s salad. No lettuce, walnuts, watercress, red peppers, feta cheese, parsley and tuna fish. Whatever wasn’t lettuce.

Mikki Fontana was American, I’m still in touch with her. She’s back down in the States now, she was David’s girlfriend at the time. She’s a vegetarian and has a very interesting and quirky way of looking at things, her films were like that too.

Mike: How did you feel about the volunteer duties?

Munro: I thought the volunteer duties were never onerous. I was at school at the time and worked the box office at the Tarragon Theatre, so the Funnel stuff was easy. I remember cleaning something once, and taking tickets, giving out programs, simple things. I helped organize some films, putting them in alphabetic order, it wasn’t very demanding. I don’t ever remembering not enjoying what I was doing. The whole thing was fun.

You never knew what the screenings were going to be like. That was great too. I thought the programming was good, I liked the mix of contemporary and historical experimental films. Most screenings were well attended unless there was really bad weather. Often there were two shows a week, that’s a lot. There was a core group that would always show up. The same people came again and again, it was like a club.

Mike: Did you go to open screenings?

Munro: They were great. I started an open series screening at the University of Toronto because we could get around the Censor Board, even though the screenings were public, university property was considered private. I organized these screenings after the Censor Board stopped the Funnel’s open screenings. People from the Funnel came, as well as many others. I should see if I have any of the posters, it was definitely an offshoot of the Funnel activities.

The open screenings were about audience participation. There were a lot of experimental films, but people arrived with home movies from childhood and sometimes pretty risqué stuff like home-made porn in one case, that was a funny night. I loved it when people brought random found footage they found in the garbage. Sometimes there were not particularly great student films, but I liked the fact that everyone was welcome. Atom Egoyan brought his second short film After Grad With Dad (1980). He worked with a very low budget, but made it look like more than what it was, that was his knack in those days. Atom was another member of the Hart House Film Board.

Mike: Can you talk about your movies?

Munro: I made a 16mm experimental black and white film with friends called Dreams of a Physicist (running time, year?). It was influenced by Man Ray, dreamy and surrealistic. I made a number of films with Pascal Sharp who was the brother of my girlfriend Eo Sharp. We made fun, colourful super 8 films using clay and toys that were almost animated. They were often satirical and anti-consumerist. We found a board game called “Loblaws Check-Out Game” and made a movie out of it. Because the game parodied itself, all we had to do was film the characters and the cards that came with the game and add some shopping muzak. The film practically made itself, it was so easy and fun to make.

Dot Tuer: “In Loblaw’s Check Out Game (6 minutes 1983) simulation is encapsulated in cardboard ladies traversing a board of miniature supermarket items while plastic shopping carts pass across the frame full of tiny replicas of consumer products. This is a ‘teeny-vision’ of the cinema, characteristic of these filmmakers’ humorous obsession with the diminutive dimensions of a reality that accompanies a consumer-oriented society. In all their works, models supplant a cinema verité, and narrative becomes a function of a reconstructed representation that operates in a closed system of toys and studio settings.” (Dot Tuer, Canada House Programme Notes)

Munro: I did a play called Mr. Potato Head on the Oedipal Stage, which was taking off from a Screen Magazine essay written by Teresa De Lauretis called “Snow on the Oedipal Stage” (1981). This eventually became a movie I made with Pascal called Greek Civilization (30 minutes 1985) that told the story of Oedipus Rex using props and toys. There were a series of tableaus quickly cut together, it looked like stop motion animation but it really wasn’t, it was even more minimal than that. We put a heavy drum soundtrack to it, if you have a really good rhythmic track and fast cutting it’s going to appear in sync. The work had a lot of energy. It came out of a DIY, punk attitude. Let’s just do it, even if it’s rough.

Mike: Did you screen your films at the Funnel?

Munro: Pascal and I never had enough material to fill an evening. We brought work to open screenings, and there was a curated series called Cache du Cinema that included a couple of our films. The Globe and Mail reviewed the show and art critic John Bentley Mays called Loblaws Check Out Game “loopy.” (laughs) I like that word loopy. There were a lot of fine films in those screenings, it was a good example of the variety of filmmakings going on, mostly by young artists, we were kids.

The Funnel was definitely not for everybody. Maybe its inclusivity was its downfall, like every organization the best thing about it was ultimately its weakness. What made it great was that it was a club, a tight group of people, a community. I moved to Montreal in 1984 and after that I had much less to do with the Funnel. Then Pascal and I received a small Ontario Arts Council grant to make Western Civilization (running time, year?) which was a reprise of Mr. Potato Head in the Oedipus story, but now we wanted to parody western views of civilization. The film began with Genesis and ended with the death of Elvis. We worked with models, sets and cardboard costumes. When it turned out there was money left over, my hope was that we would keep on adding scenes. But when we finished Pascal wanted to use the rest of the money to buy lumber to build the platform, the raked floor the seats would be bolted into at the Funnel’s new theatre on Soho Street.

Almost as soon as the theatre was built there was a dispute about someone (editor’s note: Barbara Sternberg) outside the Funnel wanting to use the optical printer (a device that copies/refilms super 8 or 16mm film, one frame at a time). David didn’t want her coming in because she hadn’t participated in building the theatre. The idea of being a “core member” was that you volunteered, it was a collective of shared work. It went against his conception of the spirit of what the Funnel was that this outsider could be allowed to use the equipment without having paid their dues. I can’t remember who she was, but she was someone with influence. I was told there was some pressure from the Ontario Arts Council to let her use it, and when the Funnel refused, the Council decided to blow it all up and shut down the organization. That’s the story I got though I might have a very distorted point of view. Does this make any sense to you?

Mike: I’ve never heard that story. Here’s what Barbara wrote me on September 23, 2013: “I had two refusals from the Funnel both of which I got around. The first time Cindy Gawel booked the optical printer for me and I came to ‘assist’ her — but she left and I did my own work. That was because I hadn’t yet done all of the necessary volunteer hours to become a member, and only members were allowed to use equipment. The next time I managed to get Gary McLaren to let me work at his house on printer, I think that must have been after the dissolution of the Funnel.”

Munro: That may have been just one of the disputes.

Mike: Do you know why the Funnel moved?

Munro: They had to leave the King Street location. It was the perfect space for them, but the lease was up so they decided to move somewhere cheaper and closer to Queen Street. They should have just stayed in the old location, it’s really too bad. I felt sad but I wasn’t there so I couldn’t say anything.

The Funnel was one of the best things going on in the art scene at that time. I liked the combination of creation and exhibition. They were also starting to create a collection of films for distribution and publish catalogues. I felt it was really working, people came together in the same place to produce a collective energy that pushed us all creatively.

Mike: Michael and Joyce were members, they showed their movies at the Funnel and attended screenings. Did you hang out with them there?

Munro: They were friends, I remember Mike talking about a film that Mikki Fontana made that he really liked it, which was unusual for him. Mike is an incredibly intelligent and fascinating person, but what he really likes to talk about is himself and his own work. It was a kind of running joke that whatever you showed Mike he would say, “Oh yeah, I did that already.” (laughs) Joyce came to screenings occasionally. I remember telling her that I was going to get involved with the Funnel and she was very supportive, she was a believer.

Mike: In the eighties Joyce Wieland developed Alzheimer’s disease.

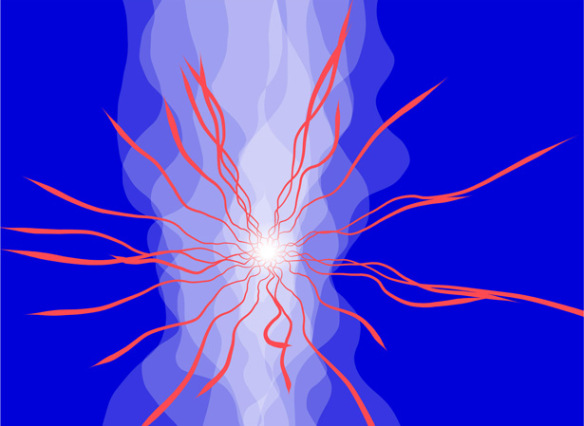

Munro: It was very sad. She had an incredible imagination and ideas pored out of her, sacred, profane and hilarious. She was a fountain of creativity, earth mother and child. She was the first person I learned about ecological issues from, the first to talk to me about vitamins when I was a kid. She had a vast range of interests, and didn’t hold it in at all. To see a mind like that slowly disappear was so painful. It started off with small memory glitches, she’d forget where her car was. My grandmother had already suffered from Alzheimer’s, so I knew what was going to happen. That’s part of the reason I made the abstract animated short June (6:45 minutes, 2004). June is about sadness and grieving, but also about the earlier part of Joyce’s life when she was such an inspiration to me and to so many others. It’s a stereoscopic animation, made using SANDDE (software) that I helped develop. Part one, “Alzheimer’s,” is about the end of Joyce’s life. Part two, “Memory,” is about what the artist was like during the height of her creative powers.

Mike: Why should make people make experimental movies?

Munro: I think after the Funnel period the pendulum swung the other way and filmmaking became much more conservative. In the 1970s even Hollywood was very influenced by experimental and avant-garde filmmaking. The eighties saw the rise of neo-conservatism and the success of films like Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) where the story was everything, and we’re still dealing with that momentum today. I get really suspicious when people start talking about stories because that’s become a code word for a conservative mode of cinema. Film students read how-to books about three act structures and this cookie-cutting approach kills creativity.

Today we’re clearly moving towards interactivity, and traditional forms of storytelling aren’t well suited for that. But the powers that be are people who grew up watching television in the 1980s, it’s a baby boomer generation that’s stuck in a neo-con view of cinema. I think they missed the boat on that. Even in traditional cinema it’s not stories, it’s the characters you remember, right? The story is just a place for characters to live. Personally, I like abstract films. I make non-representational films because I find them more beautiful. What’s really wonderful is that the audience participates by imposing their own meanings, your brain creates the story, each person in the theatre has their own interpretation of what they’re seeing.

Mike: Is abstract cinema a more democratic form because it’s less insistent on how it should be received, on what specific meanings could be taken away?

Munro: Yes, and it’s more democratic in the sense that it’s open to independent people with limited means to create. It doesn’t excluding anyone. In practice it was only a small group of us makers and a small audience. But in theory anyone can do it. Of course distribution is the hardest piece. My film June needs to be projected in 3D, and that can be difficult to arrange properly. The nice thing about projection installation, which is increasingly accepted in the museum world, is that it provides opportunities for moving image makers to work outside the limitations of theatrical distribution or television. In galleries you get the right kind of audience, with the right kind of mindset and attention. I remember John Porter talking about that, how he wanted to show movies in museums right alongside paintings, and that they would be available to watch all day. I think that’s the way to go.

I probably would never have been considered a serious experimental filmmaker because I liked to play too much while I was making. When I went into visual art I made paintings that looked like cartoons and I was asked, “Why don’t you just become a cartoonist?” I was very influenced by Pop Art. I actually wound up becoming a cartoonist, drawing a strip for the Globe and Mail called Eureka that was syndicated, I was busy with that for several years. I still wanted to make film, and wound up working on Atom Egoyan’s En Passant (In Passing) part of the omnibus Montréal vu par (1991). Oddly enough it wasn’t Atom who hired me, but another friend, Ann Pritchard, an art director in Montreal. The story was about a graphic designer who comes from Holland to Montreal and all of his thoughts are represented by pictograms. Ann asked: where am I going to find someone to make these pictograms? I was sick of my comic work so I quit and told her that I could design pictograms that express fear and anxiety. Atom was very happy working with me, he’d bring me into the edit room to look at stuff. We started animating them a little bit and that got me interested in animation, and eventually I wound up at the National Film Board doing animation. My life looped around back again, today I’m an animator making experimental films. (laughs)

It was funny growing up with experimental film and thinking it was normal. It’s a good way to be introduced to it. Both Joyce and Mike have had a really good influence on art practice in Canada. When I look at the Canadian art scene and how strongly avant-garde it remains, I think they gave courage to the rest of the visual art world, particularly the generations that came after them. They had a big influence at the Funnel, while there were other important artists like Stan Brakhage, Mike and Joyce were members and lived in town. They helped to legitimize the place, and encouraged everyone to go as far as we could.