Impressions: an interview with Martin Heath (October 18, 2013)

Janine Marchessault: “Martin Heath’s interest in cinema began with his involvement in the film societies in England in the 1950s. His first exposure to the architectonics of its circuits was through his job at Contemporary Films in London, England. Contemporary Films had been established in New York by the radical film distributor Charles Cooper to become one of the foremost non-theatrical distributors of the postwar 16mm market, expanding it to school libraries, film societies, churches and community groups.

Heath began his film career in the late fifties and early sixties when as a young man, he was hired to run the film library at Contemporary Films. He also began to build his own film collection. Although he was required to destroy extant film prints when they were damaged, all that was needed was a photograph of someone destroying the print can with an axe. Heath became adept at faking these axe deaths and rescued many films. Thus began his love affair with film repair and projection. It also introduced him to Cooper’s committed and highly politicized vision of film distribution.

When Heath moved to Toronto in the early 1970s, he moved into Rochdale at the University of Toronto… It opened in the spring of 1968 as a pedagogical experiment inspired by Marshall McLuhan who was teaching media studies only a few blocks away. Heath received a Canada Council grant in 1975 and with Chris Clifford produced a series of inflatable Mobile Cinemas which toured Ontario and other parts of Canada for three summers (1976-1978).

…Heath… came up with the name CineCycle for a space that serves as a cinema, coffee bar and bicycle repair shop. The present location of CineCyle is very appropriately in the Coach House behind 401 Richmond Street… CineCycle is also where Martin Heath lives. There is no evidence of this domesticity and it is something that is just known. But this is perhaps what produces in the experience of walking into the cinema a feeling of both exclusivity and belonging.” (from Visible City project, http://www.visiblecity.ca)

Mike: Did you ever visit CEAC (Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication)?

Martin: I went to their Duncan Street location. They had bought a four-story warehouse building.

Mike: Did you project films there?

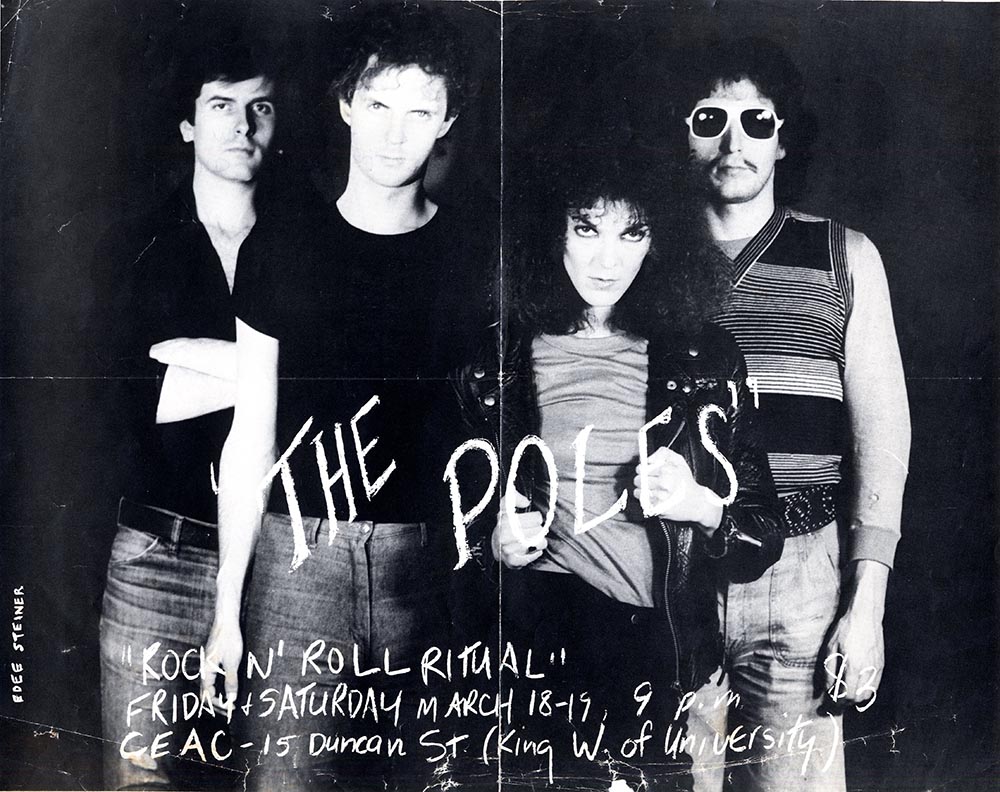

Martin: I helped people with their performances, prepping stuff. They held a little performance festival. Then of course there was the whole punk band thing that started there, the Crash ‘n’ Burn club in the basement. I didn’t attend, it wasn’t my thing. The Poles started there. They were a structured punk band with a story, they did a small, Inuit-themed opera at Innis Town Hall, I was tasked with discharging dry ice at appropriate moments. They started performing at CEAC as part of the punk scene. I remember being turned away because I didn’t look punk enough.

Mike: Did you ever meet Amerigo Marras or any of the braintrust running the joint?

Martin: Yes I did. They weren’t difficult to work with. They obviously had a lot on their plate. Everything was happening so fast. They were off to Europe for a whole summer one year doing performances.

Mike: Was CEAC primarily a performance space?

Martin: Yes, there were events instead of installations.

Mike: What made CEAC different from other artist-run centres?

Martin: It was more accessible and there was less bureaucracy. The impression I got was that if you wanted to put something on, you could get something going in a couple of months. They left space open for events, they liked to be available. It was a do-it-yourself space. Once you got in there, you had to figure out how to use it, what kind of lighting you were going to need, what area of the space you would perform in. You were on your own.

Mike: Was the audience mostly sitting on the floor, lining the walls, as opposed to a more traditional theatrical arrangement with a stage in front and the audience in seats?

Martin: Definitely. The performers were also part of the audience, they mingled together. Gordon Monahan did a performance which involved a dozen people doing improvised percussion guided by him. It was quite a while ago, I don’t really remember that much.

Mike: Was there a political project at CEAC?

Martin: I think so, though I’m not exactly sure what it was. It was a pretty edgy place. CEAC harboured anarchist tendencies, so along with the punks downstairs, there was definitely an atmosphere of rebelliousness.

Mike: Did you ever attend any of the open screenings there?

Martin: I don’t remember going to any screenings there. Most of the time I was involved with A Space. If there were any screenings at A Space, I was given the job of looking after them. In the mid-seventies, A Space brought high level artists like Vito Acconci. He had brought a sound film that ran at eighteen frames per second, it’s an anachronism, but that’s what he had. I managed to find a projector from Reg Hartt to do the job. There were a number of European artists that screened work. This one guy created multiple projections on different surfaces that required twelve projectors. In Vancouver it took a month, I did it in a day and a half. I even had a bunch of films like Alexander Nevsky that he showed extracts from on the surface of a pail of milk, he projected Joan of Arc on the breasts of a dark-skinned women. It all ran simultaneously for about a half an hour. It wasn’t a loop installation, you had to set it all up and get it going and that was it for as long as it lasted.

Mike: Was there a big division between film and video?

Martin: They were different forms. You could project film but not video. Nobody would say they were looking at a film if they were watching a TV monitor.

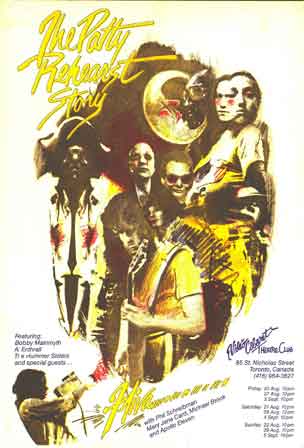

The Hummer Sisters started working on their (video performance) The Patty Rehearst Story in the basement of A Space which involved multiple television monitors. They got me to build Copacabana-style seating, which was raised along the perimeter of the room so everyone could have a small table but still see into the performing area. Eventually they got kicked out because they were hogging space. VideoCabaret started off with Michael Hollingsworth’s play Strawberry Fields, and then they started Patty Rehearsed which was workshopped at Harbourfront and developed at A Space.

VideoCabaret website: “In February 1976, The Hummer Sisters teamed up with playwright/director Michael Hollingsworth and composer Andrew Paterson on a performance for Fifty Ways to Heat Your Video, an Ontario Video Producers’ Conference organized by Lewis and Taylor. The collaboration led to the founding of VideoCabaret that summer. Joined by video artist Chris Clifford, this group of artists offered up the first VideoCabaret productions: Strawberry Fields and The Patty Rehearst Story (a video-rock musical about media-rape).”

Mike: Did A Space feel more clubby and clique-oriented than CEAC?

Martin: Yes, and as a result there were coups at A Space. There was an attempted take over by Victor Coleman that I helped torpedo. That was when Lisa Steele led a counter move. And at some point General Idea ran the space.

Mike: Victor Coleman was one of the two people who were running A Space, along with Marien Lewis who was part of VideoCabaret.

Martin: He was trying to pull a fast one. He got a group together surreptitiously to create a majority vote, all I did was to alert others this was going on. I didn’t think it was fair.

Mike: Were there tensions between A Space and CEAC?

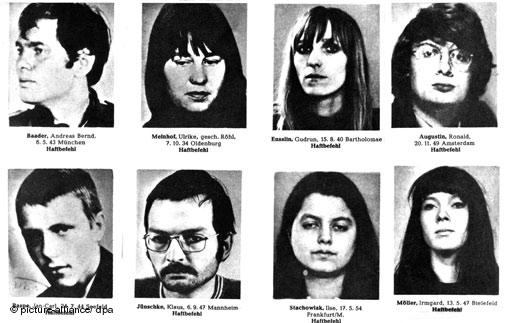

Martin: There was a chasm between them mainly because of the politics. I don’t think A Space was very political but the CEAC people were. This was when the Baader-Meinhof group was operating.

Wikipedia: The Red Army Faction (RAF), in its early stages commonly known as Baader-Meinhof Group (or Baader-Meinhof Gang), was West Germany’s most prominent left-wing militant group. The RAF was founded in 1970 by Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Horst Mahler, and Ulrike Meinhof. The RAF described itself as a communist and anti-imperialist ‘urban guerilla’ group engaged in armed resistance against what they deemed to be a fascist state. It existed from 1970 to 1998, committing numerous operations, especially in late 1977, which led to a national crisis that became known as ‘German Autumn.’”

Mike: The Baader-Meinhof were no artist-run centre, but they were a small group of people creating actions and performances, and issuing texts, that railed against state violence and imperialism. Was CEAC unique in its sympathies for these forms of resistance? Has there ever been an artist-run centre in Canada that was onside with these strategies?

Martin: Not that I’m aware of.

Mike: Were you surprised by the Toronto Sun headlines and articles decrying CEAC as a terrorist organization, and the subsequent withdrawal of funding from the arts councils?

Martin: If you were close to them at all, you knew that was the direction they were sympathetic to. It wasn’t a surprise that their funding was cut.

Mike: They didn’t get a lot of support from the community. Was it a strategic failure not to build more support?

Martin: They weren’t supported because they were so extreme. I don’t think they cared much about building support. If they wanted to, they could have held onto that building which must be worth five million dollars now. But of course they’re not around to do that.

Mike: Do you remember when you first heard about the Funnel?

Martin: Not exactly, but I remember a description of how the logo came into being. One of the members (Adam Swica) wrote it out. I must have gone there fairly early on and got the impression it was a cliquey group. They weren’t exactly welcoming so I didn’t go back for a while.

Mike: What gave you that impression?

Martin: They were all experimental filmmakers while I was working in the commercial film business. I was outside of what they were doing.

Mike: But you were very deeply involved with the alternative art scene and artist projections, a project that seems entirely congruent with the aims of the Funnel.

Martin: Yes, but most of their activities were centered around the space of the Funnel. I didn’t have any money, so I didn’t consider joining. You had to apply to join anyways, in order to use the facilities you had to become a member. Let’s put it this way: no one encouraged me to join.

Mike: Did you know Jim Murphy at the CFMDC (Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre), a key friend of the Funnel?

Martin: Jim Murphy was a very big, boisterous, jovial fellow. I also knew other people who worked there like David Tompkins who was pretty much a maniac. He booked films. He was responsible for bringing Californian Freude Bartlett to town for the Women in Film Festival in 1974 that I worked on.

Mike: Freude was the founder and manager of Serious Business Company that started in 1972 to distribute women’s movies and so-called underground cinema.

Martin: David Tompkins got Freude to come and show Anne Severson/Parker’s Near the Big Chakra (1971) for the last night of the festival. There was government money behind it, and it was held at the St. Lawrence Centre. The programs mixed experimental and narrative work and proved that audiences were ready to come out and support a film festival. This became the launching pad for the Festival of Festivals, the international festival that began a couple of years later.

IMDB: “(Near the Big Chakra features) Extreme close-ups of 38 vulvas, aged three months to fifty-six years, including two blacks, one half-oriental girl, two lesbians, one prostitute, two adult virgins, three mothers to be, three grandmothers, four women menstruating, one girl with gonorrhea (learned just days after the shoot), a woman who learned she had uterine cancer three weeks after the shoot, and a lot of mothers. Intended as an educational film by and for women, but screened to mixed audiences, the women photographed were mostly friends and acquaintances, or children of friends and acquaintances, of the director. The Glide Methodist Church’s education division, which specialized in community service related to sexuality and pregnancy, produced the film.”

Martin: David Tompkins had connections everywhere. He told me that he had obtained driver’s licenses and been banned from driving in every province across the country. He’d lose his Ontario license then go to Quebec and get a license there. He’d lose that and go to New Brunswick for another. I once made the mistake of lending him my vehicle. The next thing you know cops are banging on the door. They wanted me to pay for an accident, but I told them that I had lent the car to Tompkins. This was in the days when there wasn’t any insurance, you had to buy an eighty dollar license from the government, and if there was a problem you had to pay up for the damages. There were no million dollar settlements in the seventies. I bought the original vehicle in Vermont, a state that didn’t require insurance. So I drove it back to Canada without insurance and Vermont plates and it was perfectly legal.

Mike: Were there other alternative projections going on in the seventies?

Martin: In 1975 Noah Dakota ran a cinema club that started in Cinecity, just under the post office, before moving uptown, north of Eglinton on Yonge Street. He ran alternative 16mm American underground programs in a basement space that would have included work by artists like Bruce Connor and Kenneth Anger. I don’t remember paying a membership. Who would go? You’d assume it would be film students.

Mike: How did the Funnel space strike you?

Martin: They had made a big effort to built the space, influenced perhaps by the Anthology Film Archives in New York. It was a long narrow room and they had installed risers and raked seating. There was a projection booth in the back. I don’t think they had Xenon projectors, but the projection was OK. They showed super 8, and made super 8 films there as well. They had some kind of super 8 editing system, but of course that was only available if you were a member.

Mike: Was super 8 unusual at that time?

Martin: No, it was a format that was in use. I would sometimes project super 8 for other people.

Mike: Did the CEAC’s political project carry on at the Funnel?

Martin: No. The Funnel was interested in experimental films, and that could be pretty much anything from abstract or animated work to diary films. The main tone of events at CEAC was about protest, and that didn’t come over to the Funnel until there was persecution by the government of Ontario via the Censor Board. They were shut down, though they weren’t the only ones who had problems. The Film Festival (TIFF) had a big run in with the Censor Board as well. The Board was run by the infamous Mary Brown and they were pretty hard line. It wasn’t until the Conservative government was voted out that the Censor Board issue was resolved in a compromised way, you could show anything in a festival context, but not to the general public in a daily program.

What the government does when they want to shut you down is they send in the fire inspectors. When the inspectors came to the Funnel they decided that the place was a firetrap and needed drywall over every surface and that shut them down for a time.

(Several years later) the Funnel tried to reopen on Soho Street and that was a dismal failure. I couldn’t see how they were going to do anything, and they didn’t. So many people had abandoned ship, there was no one left. The group lacked motivation. The original space was pretty gung ho, they got crews in there and worked away at it. They achieved something. But that energy was no longer there when the move happened. And there was infighting around ownership of the equipment. People still don’t know what happened to the gear. I certainly didn’t get any of it.

LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) had restarted by then, an equipment co-op that soon replaced what the Funnel had been doing in terms of their production equipment access for members. The Funnel was primarily an exhibition space, and that became their downfall when they were caught out by the Censor Board.

Mike: You hosted American filmmaker and performance artist Jack Smith during his four night performance of Brassieres of Uranus in October 28-31, 1984.

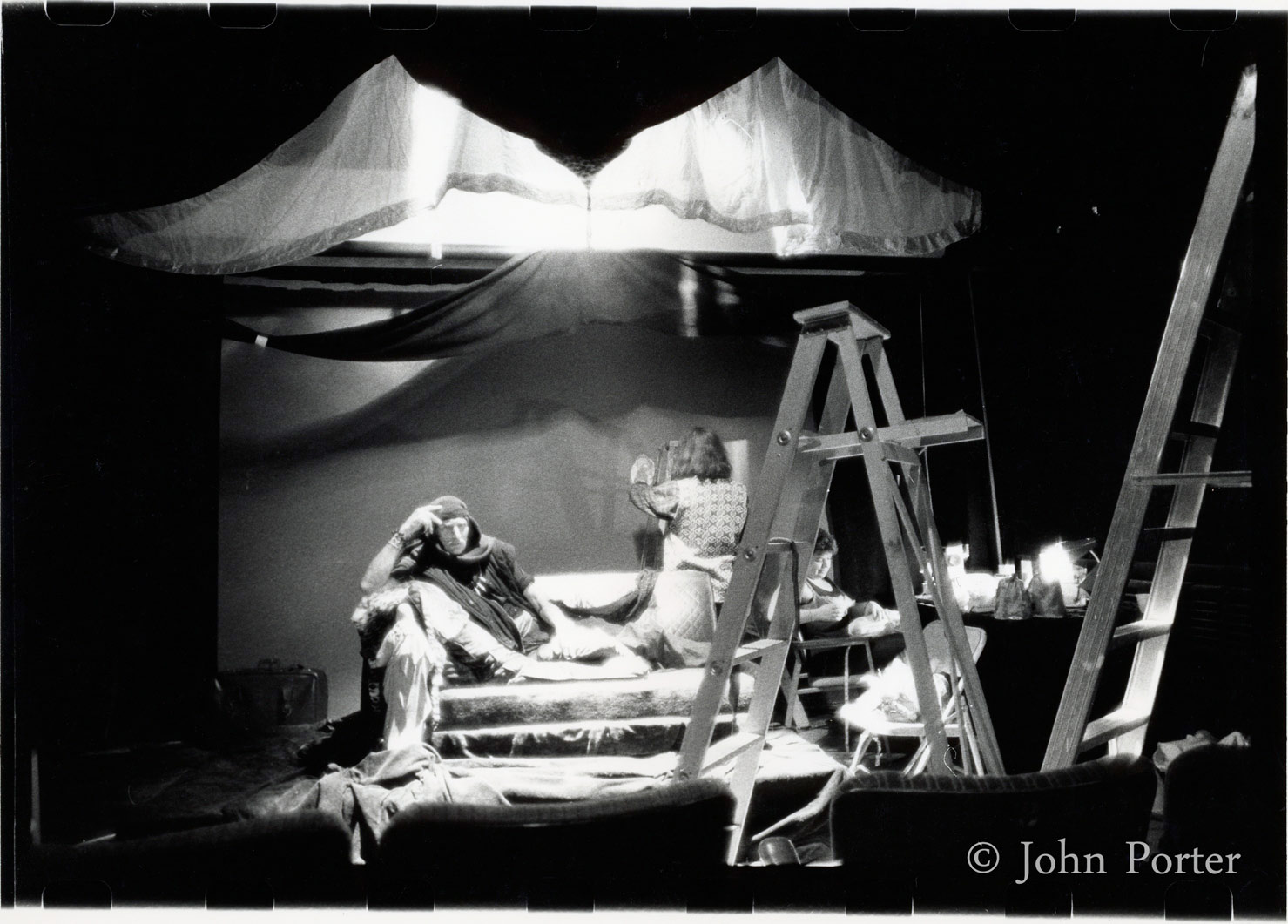

Martin: Gordon W told me that Jack Smith had performed at the Funnel last night, and he’s going to be there for the next three nights. We’ve got to go. It turns out that on the opening night, David Buchan, a local performance artist, was naked on top of a step ladder. He was probably wearing angel wings or something. Jack Smith did his usual thing, which is to do nothing until people who were bored easily left. People who were truly interested, or felt that something might happen if they stuck around, stayed. Well, that didn’t happen because everybody left but Gordon.

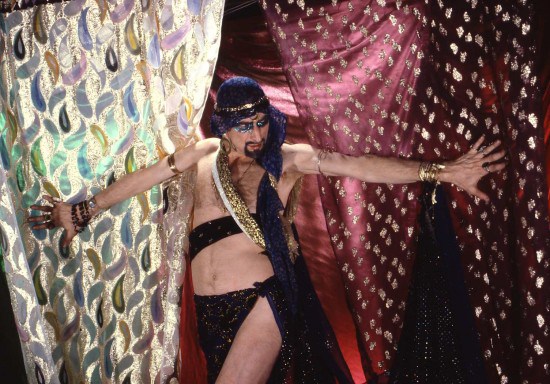

When Gordon and I arrived the next night, no one was there. I’d lent a cello to a woman who was playing onstage, and in the next couple of days I borrowed a leopard skin for Jack Smith to sit on from Jamie Hart, who was a local couture artist who made clothing. Gordon and I also got involved in the performance. The only people in the audience were Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland. I was trying to film Jack Smith, and made various costume changes, and produced large Chinese flags. Jack mostly reclined on his couch. He ended up staying at my place for a week while this was going on. As a house guest he was cranky as he always was. A few years later, Gordon went to visit him in New York and took him out to the country when he was really sick (Jack died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1989).

Mike: Was he disappointed in the reception of his work?

Martin: Yes, I think he depended a lot on the audience for his performances. On the other hand he made films and there’s no audience while shooting. He didn’t bring his films.

Mike: Did his performances seem unusual?

Martin: He’s unique, you can’t compare him to anybody else. The fact that he could motivate me to become involved in his performance is also unique. It’s something I never do. He was very charismatic.

Mike: Did you feel that Jack had a political program?

Martin: His political program was exoticism. The music and costumes. It was the opposite of entertainment, his performances demanded an engagement with exoticism, he created an awareness around the need for it. Rather than being simply affected by performance, or consuming it, you could watch the need arising and that took time. When he performed in New York some people were always going to leave, but others knew what it was about. In Toronto no one knew.

Mike: You’ve seen the experimental movie scenes run through many changes in the last four decades. How would you characterize the scene at this moment as opposed to thirty years ago?

Martin: If there is a scene I’m not really in touch with it. I don’t really go chase around town going to things. I host events here (at Cinecycle), that’s what I see mainly. I think the experimental screenings that happen are exploratory and valuable, unique in their own way. Though little of the work is political motivated.

Mike: It’s purely aesthetic?

Martin: Pretty much, yes. Unless you’re talking about rap music which can get political.

Mike: Have the experimental film scenes as they’ve developed remained separate from political content and engagement?

Martin: Usually, yes.