Jorgen Leth: Translucent Being

The Five Obstructions, a movie made with (and despite) Lars Von Trier has pushed Jorgen Leth further into visibility on the global stage, but there are long lines of light that led to that one. For five days at the International Festival of Documentary Film in Jihlava we can conduct investigations of our own, running these beautiful pictures over our eyes. These coolly observational moments are the result of a restrained celebration, an embrace that knows the cost of refusal. In film after film Leth returns as the spurned lover, burned, left out to dry, but back again. The pleasures he offers are more deeply felt for having been denied him, they surprise him, and so he is determined more than ever to find the life in these passing moments, and to keep passing them right along.

In A Moment of Play (82 minutes 1986) the camera is curious, inviting us to look, taking these in-between moments of playtime seriously. The camera is up close and personal, filling the screen with faces which grimace and hope and sing, with hands that carve and roll balls and beat drums. Over and again he starts close, so very close to make us part of the scene, to connect these bodies with our own. And then he pulls back to show us where we are. Oh, a street in Bali. A sunset in Brazil, Spain, China, Denmark, England.

The voice-over belongs to the director and always begins in the first person. “I pass the time away. I disappear into my dreams. I must do it right.” No matter that we are watching young children playing with a baby crocodile, a Californian bouncing a ball off his body, young boys shooting bows and arrows. It’s me. It’s always me. His voice-over, his presence, is continuity and explanation. But did I mention how beautiful this film is? Not just rope skippers but twilight against a New York skyline. It’s not necessary perhaps, he does it for pleasure and part of the pleasure of looking is beauty, the heavenly light from the attic window which turns a boy’s toy train into dreamscape. And how graceful and beautiful these bodies are, as if the body was made for play after all, and not work. On the rollerblade track everyone turns to their own Walkman, each body carries a song of its own which sings in the presence of others, producing not cacophony but the simple addition of pleasure.

“We envisage a playful, elegant film. One shouldn’t be afraid of repeating oneself. On the contrary; great artists return to the same themes. Without wishing to compare ourselves to them, we will adopt the same working model. Simple means. Black and white film. Highways, motels, (Robert) Frank, Edward Hopper, and then Leth and Homberg. Today at around the turn of the century. What does America look like when we seek out the visual templates that are so expressive?” Here Leth writes about New Scenes from America, update and revision of his 1981 short 66 Scenes from America. Each proceeds episodically, as a series of postcards, looking at iconic moments of Americanarama (cocktails, beach scenes, musicians and actors) many named in a hilarious straight man accent provided by Leth himself. Celebration or denunciation: Leth leaves it up to his viewers.

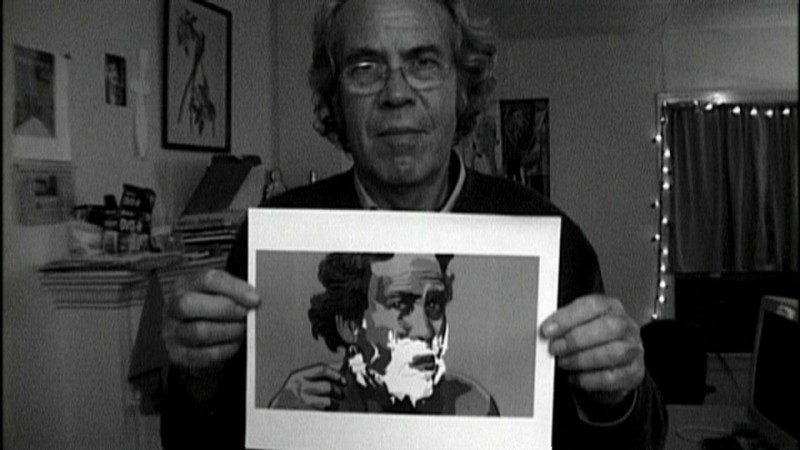

Strange to think of The Five Obstructions (Jorgen Leth and Lars Von Trier, 90 minutes 2003) as a collaboration. An oedipal saga, a confrontation, a love letter between two (the only two, the lonely two) who can’t bear to speak this word, not between one another, this is the obstruction that lies behind all the rest. TFO examines the director as superstar trickster. Lars Von Trier, the haunted one, haunted by his own talent, has established for himself a series of prohibitions over the years, the Dogme rules are the most well known, but there have been others underlying his work from the very beginning, when he was a technical geek (how did he DO that?), able to do anything and more his mind turned itself to, but finding the work empty and unsatisfying (the difficulty of first world success: what to do with too much?) When there’s this much talent involved one must invoke again the taboo, the moral dividing line, and the results have been splashed across cinema screens around the world. Needless to add that this work has been born of suffering (Von Trier is a traditionalist after all, like every innovator). In The Five Obstructions he appears as devil’s advocate, reaching back into his own past to pluck his cinematic father Jorgen Leth (once his teacher, the source, the body where cinema resides) and asks him to remake his own film The Perfect Human (13 minutes 1967) five times, each time with a new series of ‘obstructions.’

Why is happiness so brief?

“Jorgen you’re looking great, that’s not so good,” remarks Von Trier as Leth makes his way back after the first obstruction is complete (no shot over twelve frames, to be shot in Cuba without sets). Von Trier is looking for a way to break the habit of being human, the shell of personality we carry around as armour, in film after film, in obstruction after obstruction, but Leth sails through, apparently untouched. Comrades of despair, their correspondence before the movie (the offscreen space, the prelude) has dwelt at length about their lingering depressions, and from this stricken, lonely place they have found a way back into the world, Von Trier into the emotional strip shows of staged drama, Leth into globe trotting, watch and wait documentaries, each allowing themselves that rarest of pleasures: to celebrate and then to share their own obstructions.

Originally published in: Dok Revue, a newspaper published by Jihlava International Documentary Festival, 2004.