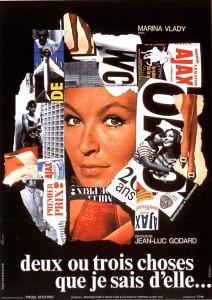

The following is Craig Keller’s English translation of an interview by Jean-Marc Lalanne with Jean-Luc Godard, dated May 18th, 2010, in the French cultural weekly Les Inrockuptibles.

Godard: I’m against HADOPI, of course. There’s no intellectual property. I’m against estates, for example. That the children of an artist might enjoy the rights of their parents’ body of work, why not, until they come of age. But afterward — I see no evidence that Ravel’s children are getting their hands on the rights for the Boléro…

Lalanne: You don’t claim any rights over the images that any artists might be lifting from your films?

Godard: Of course not. Besides, people are doing it, putting them up on the Internet, and for the most part they don’t look very good… But I don’t have the feeling that they’re taking something away from me. I don’t have the Internet. Anne-Marie [Miéville, his partner, and a filmmaker] uses it. But in my film, there are images that come from the Internet, like those images of the two cats together.

Lalanne: For you, there’s no difference in status between those anonymous images of cats that circulate on the Internet, and the shot from John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn that you’re also making use of in Film Socialisme?

Godard: Statutorily, I don’t see why I’d be differentiating between the two. If I had to plead in a court of law against charges of filching images for my films, I’d hire two lawyers, with two different systems. The one would defend the right of quotation, which barely exists for the cinema. In literature, you can quote extensively. In the Miller [Genius and Lust: A Journey Through the Major Writings of Henry Miller, 1976, JML] by Norman Mailer, there’s 80% Henry Miller, and 20% Norman Mailer. In the sciences, no scientist pays a fee to use a formula established by a conference. That’s quotation, and cinema doesn’t allow it. I read Marie Darrieussecq’s book, Rapport de police [Rapport de police, accusations de plagiat et autres modes de surveillance de la fiction / Police Report: Accusations of Plagiarism and Other Modes of Surveillance in Fiction, 2010], and I thought it was very good, because she went into a historical inquiry of this issue. The right of the author — it’s really not possible. An author has no right. I have no right. I have only duties. And then in my film, there’s another type of “loan” — not quotations, but just excerpts. Like a shot, when a blood-sample gets taken for analysis. That would be the defense of my second lawyer. He’d defend, for example, my use of the shots of the trapeze artists that come from Les Plages d’Agnès. This shot isn’t a quotation — I’m not quoting Agnès Varda’s film: I’m benefiting from her work. I’m taking an excerpt, which I’m incorporating somewhere else, where it takes on another meaning: in this case, symbolizing peace between Israel and Palestine. I didn’t pay for that shot. But if Agnès asked me for money, I figure it would be for a reasonable price. Which is to say, a price in proportion with the economy of the film, the number of spectators that it reaches…

Lalanne: In order to metaphorically express peace in the Middle East, why do you prefer to sample one of Agnès Varda’s images instead of shooting one on your own?

Godard: I thought the metaphor in Agnès’ film was excellent.

Lalanne: But it has nothing to do with that, in her film…

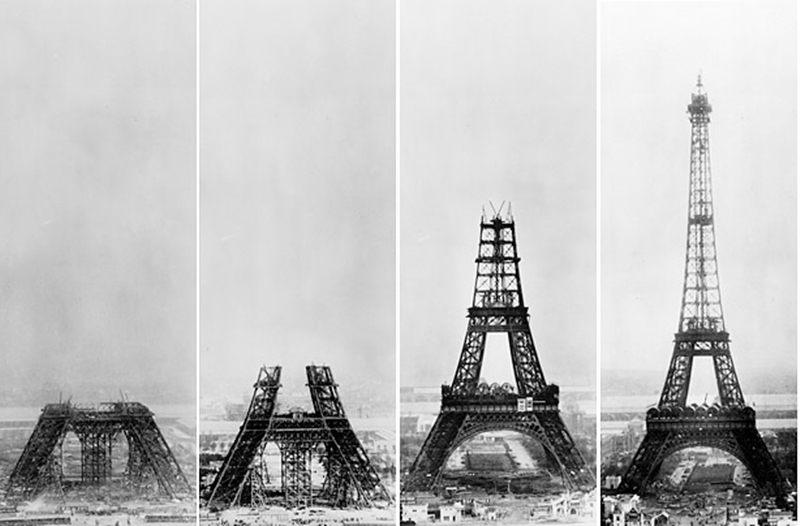

Godard: No, of course not. I’m the one who builds it, by moving the image. I’m not thinking of harming the image. I thought it was perfect for what I wanted to say. If the Palestinians and the Israelis put on a circus and brought together a bunch of trapeze artists, things would be different in the Middle East. For me this image shows a perfect agreement — exactly what I wanted to express. So I’m taking the image, since it exists. The socialism of the film is the undermining of the idea of property, beginning with that of artworks… There shouldn’t be any property over artworks. Beaumarchais only wanted to enjoy a portion of the receipts from Le Mariage du Figaro. He might say, “I’m the one who wrote Figaro.” But I don’t think he would have said, “Figaro is mine.” This feeling of property over artworks came later on. These days, a guy attaches lighting to the Eiffel Tower — he gets paid for it; but if you film the Eiffel Tower, you have to pay this guy something on top of it…