I wanted to take up this question of how to take a photograph, how to make a picture. And this question is related to the more fundamental question underlying photography, underlying all of art: how do I look? It’s a very simple and complicated question. I’d like to take up one piece of that question today.

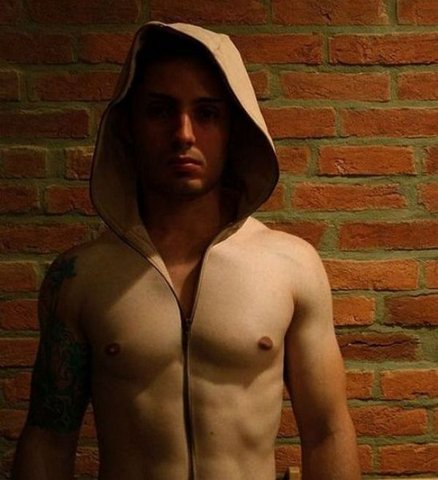

The usual way of talking about, or describing, how we see, begins with an observer, with the looker, the person who looks. I’m inside this skin fortress, this perimeter of skin, and then there’s a thing over there, on the outside. There’s an inside and an outside, there’s a subject, the “I,” and there’s an object. So even though it might be your face, I’m the one expressing myself when I make a picture of it. I’ve heard seeing described this way over and over again. It’s the dominant habit pattern. And of course it’s possible to use everything you’ve learned in this course — the tools of shutter speed, aperture, depth of focus, lighting ratios — it’s possible to use these tools to create the “me,” the subject, the visionary, the one who sees.

But it’s also possible to describe seeing in another way. The impulse to photograph usually comes out of an encounter between the contact of two energies, two momentums, two faces.

I wanted to lay out some words by the brilliant English critic John Berger in The Shape of a Pocket.

“When a painting is lifeless it is the result of the painter not having the nerve to get close enough for a collaboration to start. The painting, or the photograph, stays at a copying distance.” I love this word he uses: collaboration. The photograph isn’t taken only from the “me” side of the camera, it’s made from both sides of the camera. Even if you’re making a picture of a flower, or dust on a window, or a crack in the sidewalk. If it’s a collaboration it means that you’re working together, it’s stereo, it’s not mono. It’s not just you with the camera looking out, you’re also being looked at, you’re receiving the look. These two looks meet on the plane of the photograph.

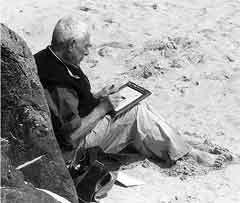

What would it mean to walk into a landscape and open yourself to being part of that place, to receiving that place? Before picking up the camera and making a picture, of asserting: I was here!

Check out this riff from Thomas de Zengotita’s Mediated: “Say your car breaks down in the middle of nowhere – the idle of Saskatchewan, say. You have no radio, no cell phone, nothing to read, no gear to fiddle with. You just have to wait. Pretty soon you notice how everything around you just happens to be there. And it just happens to be there in this very precise but unfamiliar way. You are so not used to this. Every tuft of weed, the scattered pebbles, the lapsing fence, the cracks in the asphalt, the buzz of insects in the field, the flow of cloud against the sky – everything is very specifically exactly the way it is, and none of it is for you. Nothing here was designed to affect you. It isn’t arranged so that you can experience it, and you didn’t plan to experience it. There is no screen, no display, no entrance, no brochure, nothing special to look at, no dramatic scenery or wildlife, no tour guide, no campsites, no benches, no paths, no viewing platforms with natural-historical information posted under slanted Plexiglas lectern things – whatever is there is just there, and so are you.

You begin to get a sense of what it would be like it you weren’t the centre of it all.”

Does this seem like a strange place from which to speak about photography? How often are cameras used as part of our necessary defense networks to keep the flood of sensations and informations from drowning us? When we feel anxious, depressed, uncertain, when we encounter something that needs a caption, that feels “new” (ie. uncontrolled, uncontained) we might reach for our camera and take a picture of it, in order to contain it. Gotcha. Now it’s a little smaller, more manageable, I have it in the portable, carry-all archive that cameras have become. And once I’ve taken a picture, I never need to see it again. How often do we look back over our pictures, pore over our snap taking? Who has the time? So often we are taking pictures not in order to open us up to experience as it is, but to protect us from what might be happening. And one of the first ways we protect ourselves is by hunkering down behind the “me” that looks out from the armoured shell of our skinbag and takes pics of events “out there.” Could we use photography to do something else but relive this old habit pattern?

The radical invitation of photography is to work in stereo. Stereo: it means two channels, listening and speaking. It insists: listening is part of the act of speaking. I think we’ve all experienced people at a party who just go on and on, they never stop talking, and why? Because they don’t know how to listen, and if you don’t know how to listen, you don’t know how to talk. Talking and listening are part of the same gesture. The inhale is part of the exhale. Looking and being looked at, both are part of the same gesture. Being looked at, opening yourself to someone or something else, is as important as the act of looking. Looking out means looking in, extrospection is introspection.

What if picture making were not only a me practice? What if it was taken up, as Berger urges us to do, as a collaboration? What does collaboration look like as a practice? How do you do it?

Let’s take an example. Maybe you’re shooting a picture with your brother, your grandmother, your partner, your best friend, with someone you know. Part of what you’ve shared together is a history of looking. There is a trail of looking, a trail of lookings that you share, and these lookings are often underlined and accompanied by language (did you see what I see? How do you feel about that… boyfriend, movie, teacher?) These lookings go back and forth between you and your friend, and sometimes they sound like language. (Sometimes we look with our words.)

When I’m with my friends I don’t sit inside my armoured skin vehicle with the dark mirrored glass so no one can see inside, but I can see outside. When I’m with my friends I meet them with an inhale, the collar bones widen, the hip flexors relax, in other words, I meet my friends with my whole body, my whole body-mind. I see my friends, we meet each other, with our whole bodies. Seeing happens with the whole body. I meet them with an inhale, I take them in, and I open myself, I let them see me, and I find them with a look on the exhale. We inhale and exhale each other with our eyes, with our whole body of seeing.

And if we’re friends for a long time it’s not a clean smooth ride. What did you call me? How could you have let me down like that? Real life means being hurt by the ones we open to the very most, and being able to hold that. Does everyone around us need to be perfect? Can we live in this imperfect world, make pictures of this imperfect world, and allow these pictures to spread so we can relieve ourselves of ideals that are only the pretexts for self punishment?

I think the practice of seeing, of collaboration, has something to do with being in a body. A steep proposition in this culture, which has dedicated itself to the systematic eradication of the body’s sensations. Our sense hierarchy, which puts seeing (the most distant and abstracting of all the senses) at the top, seeing is most important, then the other senses follow. It helps keep our bodies faraway, where we can regard them as objects. But collaboration invites us to step back into the body, to take the risk of being a body amongst other bodies, to imagine that we are in relationship, and to see out of that place of relationship.

So if we want to take up collaboration as a practice, we’d like to try and stay inside our bodies, these hated and unwanted bodies that school teaches us is only a meat pedestal for the important part of us, which is our heads. Our beautiful minds. And if the mind is beautiful the body is… at the very least, something less. It seems incredible to me that one could graduate from this course without a single physical task, beyond occasionally climbing onto a bus, or up the stairs. There is no explicitly physical aspect to this practice, though as our cameras helpfully remind us, seeing is a question of bodies, you take up the camera body in order to see with it, to relearn the adventure of seeing.

Could we wake up to our bodies when we’re in the company of our friends. Can we leave behind for a moment our beautiful ideas, the metaphors and abstractions which we love so much because they keep us from feeling anything, but can we be present in your body and notice what is happening as we meet our friends, in those moment-by-moments of encounter? And might we extend this noticing, this being aware of sensations coming and going, from two sides, could we extend this into the practice of photography?

What I’m suggesting is that friendship, the physiology of friendship, the exchange of sensations, might provide the basis for an art practice. Because photography is always about relationships, even the most abstract photograph. There is always a question of distance. How far away do I stand? How close are we to each other? The question of distance in photography is also a question of ethics. How close? How far? Photography is a practice of, a demonstration of, ethics. Sometimes our pictures show us how far away a face can be that we have lived with all of our lives. What am I risking in this picture, in other words, what are the stakes in my practice? What is at stake in this moment? If nothing is at stake, then why should strangers care, why should they bring their stakes to these pictures? Could photography be a way to project the ground of intimacy (with all its confusions, doubts, angers, difficulties)?

Let’s close out with a long riff from John Berger, one more time from The Shape of A Pocket (Bloomsbury: London, 2001)

“Bogena and Robert and his brother Witek came to spend the evening because it was the Russian new year. Sitting at the table whilst they spoke Russian, I tried to draw Bogena. Not for the first time. I always fail because her face is very mobile and I can’t forget her beauty. And to draw well you have to forget that. It was long past midnight when they left. As I was doing my last drawing, Robert said: This is your last chance tonight, just draw her, John, draw her!

When they had gone, I took the least bad drawing and started working on it with colours – acrylic. Suddenly, like a weather vane swinging round because the wind has changed, the portrait began to look like something. Her ‘likeness’ now was in my head – and all I had to do was to draw it out, not look for it. The paper tore. I rubbed on paint sometimes as thick as ointment. At four in the morning the face began to lend itself to, to smile at, its own representation.

The next day the frail piece of paper, heavy with paint, still looked good. In the daylight there were a few nuances of tone to change. Colours applied at night sometimes tend to be too desperate – like shoes pulled off without being untied. Now it was finished.

From time to time during the day I went to look at it and I felt elated. Because I had done a small drawing I was pleased with? Scarcely The elation came from something else. It came from the face’s appearing – as if out of the dark. It came from the face’s appearing – as if out of the dark. It came from the fact that Bogena’s face had made a present of what it could leave behind of itself.

What is a likeness? When a person dies, they leave behind, for those who knew them, an emptiness, a space: the space has contours and is different for each person mourned. This space with its contours is the person’s likeness and is what the artist searches for when making a living portrait. A likeness is something left behind invisibly.”