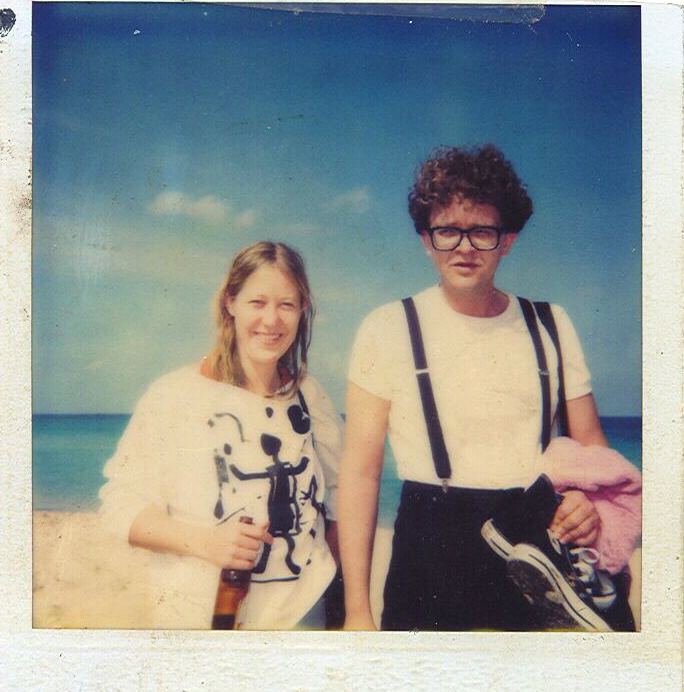

Dot Tuer and Frans Hals

detail from “Overtime Dream” painting by Jim Anderson

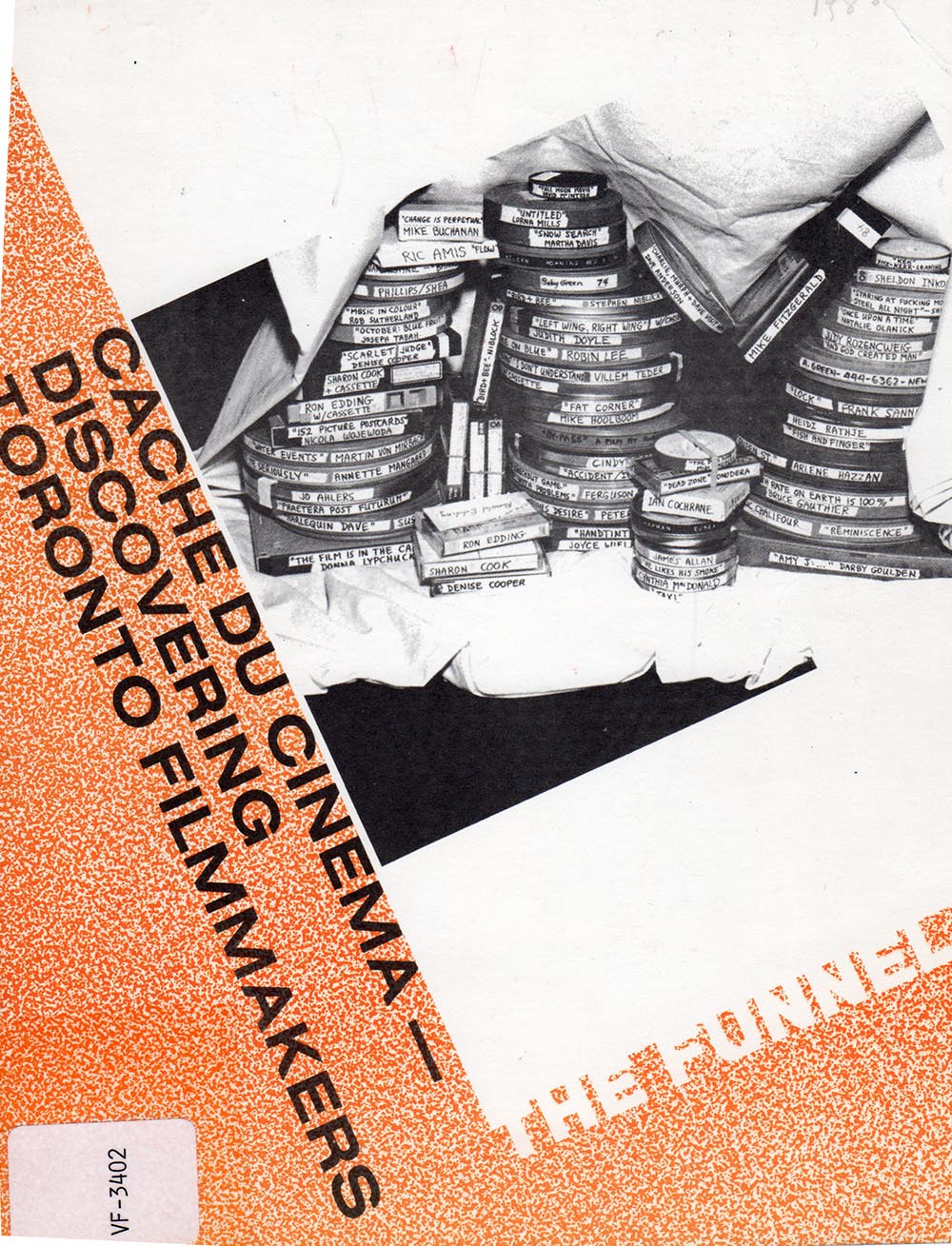

Mike: How did you hear about The Funnel, Toronto’s underground movie theatre?

Dot: My story is very atypical. I’d grown up here but had been living in Paris where I attended many screenings at the Cinémathèque Française and was involved with the alternative visual arts and anarchist communities. That’s where I began my education in experimental cinema. I came back to Toronto looking for a similar arts milieu but couldn’t read the codes, I couldn’t figure out where the artist communities were located. This grey grid of a city was opaque for me in comparison to Paris. I’d been back about a month when I read an article in the Globe and Mail about a screening that was taking place at The Funnel of Bruce Elder’s work (footnote? “Film leaves a trail of devastated viewers,” by Bart Testa, The Globe and Mail, January 1983). I sat through a very long film and felt that I had found Toronto’s Cinémathèque.

Mike: Do you remember your first impressions?

Dot: Yes! It felt like home almost immediately. I started attending the Funnel’s bi-weekly screenings, going to both the historical programs that Kathy Elder curated and the Friday night showcasing of contemporary artists’ work in experimental cinema. There was something quite unique about The Funnel, in that you could get to know all the local artists (and international ones) working in experimental cinema by the sheer amount of screenings one attended. I became even more involved when I was looking for a place to live and there was space to rent in Jim Anderson and John Porter’s studio, which was around the corner from the Funnel. Once I moved in, I was de facto integrated into the Funnel world. Our warehouse had a big social space in the middle and there were a lot of gatherings, mostly oriented around the Funnel.

Mike: How many would attend a typical screening?

Dot: I remember it being, shall we say, respectable. It always felt full and dynamic, because the theatre has a hundred-seat capacity. Some of the historical screenings had thirty or forty people, and would draw film students from York University and the University of Toronto. For high profile international guests or local screenings (because people always come out to support their own) the theatre would be packed. It was very different than video events at the time that were held in gallery spaces rather than in a theatre. Film was by its very nature a social medium. You (meaning Mike) always sat in the front row, what are your recollections?

Mike: I think fifty was average. My impression was that you would see the same people at each screening. What was yours?

Dot: I remember there being a loyal core of Funnel members, a collective of thirty people who came every week. Their dedication and sense of commitment meant that the collective functioned as a community. People affiliated with other film groups would come and go; some were involved with the Innis Film Society, or Sheridan College (Rick Hancox, Richard Kerr, Phil Hoffman). The first time I ever met (York University professor) Seth Feldman, when he was reviewing the first curatorial program I did at the Funnel, Cache du Cinema, he intimated that he saw the Funnel collective as a kind of cult. He suggested to me that I should go to York and study film there, instead of hanging out at the Funnel, which people from the outside saw as a closed, inward-looking group. Yet, ironically, of all the artist-run centres in Canada, the Funnel was the least inward looking and the most connected internationally through a network of film centres. In the 1980s we were the only ones who saw it as essential to our vision of who we were. Our network included centres in New York, San Francisco, London, Paris, Eastern Europe, and Japan. When you travelled there was a built-in experimental community that you could hook up with.

Mike: (Filmmaker and Funnel member) Judith Doyle said that the most important part of the Funnel were the relationships.

Dot: For me, the most important thing about the Funnel was that by participating in a community, people made work together and for each other. If it was just a social club, that would be relational. The Funnel was a shared and collective project to think about and make films. It closed because the project was based on a certain notion of experimental cinema. The Funnel unraveled not only because of interpersonal issues, but around questions of what constituted experimental cinema, and where it should be going. There were debates about larger productions and the place of narrative versus more structural or collage work.

Relationships at the Funnel were important and integrated through making as well as seeing work. There was the geek boy club, the tech boys, but they were always willing to help whenever they could. The environment was supportive and open in terms of what was valued as filmmaking. I made short super 8 films (though most of my work was as a writer) that would be accorded the same attention as optically printed movies by the tech boys, where the emphasis wasn’t on a conceptual framework but on material processes. We also did a lot more than meeting twice a week to see movies and making films. People curated, put out catalogues, sat on boards, went to parties.

So many years later, it is amazing to think that out of the four faculty at OCAD who have been given the University’s Distinguished Research and Creative Practice Award, three of us were Funnel members: David McIntosh, Judith Doyle and myself. We were part of a collective of young artists. We made films, wrote about films, distributed films, watched films and talked late into the night about films. These late nights for me were often conversations with Judith Doyle and David McIntosh, and if my recollection serves there might have been a bottle of Scotch.

Mike: Was there a Funnel aesthetic, a recognizable groupthink form of filmmaking?

Dot: That’s what people perceived from the outside. In jest, I would say that the Funnel aesthetic was: no more than an hour. And if you were John Porter, there is a reason that Super 8 reels are three minutes long, because anyone can watch three minutes, but anything longer than that should be eliminated. The Funnel’s aesthetic is hard to pin down because it was part of a larger international conversation about experimental cinema. It was firmly rooted in a modernist ethos, it owed its roots to structural filmmaking, material processes, and a firm notion of the avant-garde. It had an allegiance to non-linear forms developed by auteurs. It’s interesting in retrospective to see the incursions of postmodernity, feminist politics and gay liberation within the Funnel aesthetic. Psychoanalysis had a distinct position at the Funnel as opposed to the way that Bruce Elder or Stan Brakhage understood it. At the Funnel, psychoanalysis was part of a feminist and post-structural vision of what experimental cinema could be, not about male filmmakers who thought about the feminine as their unconscious muse.

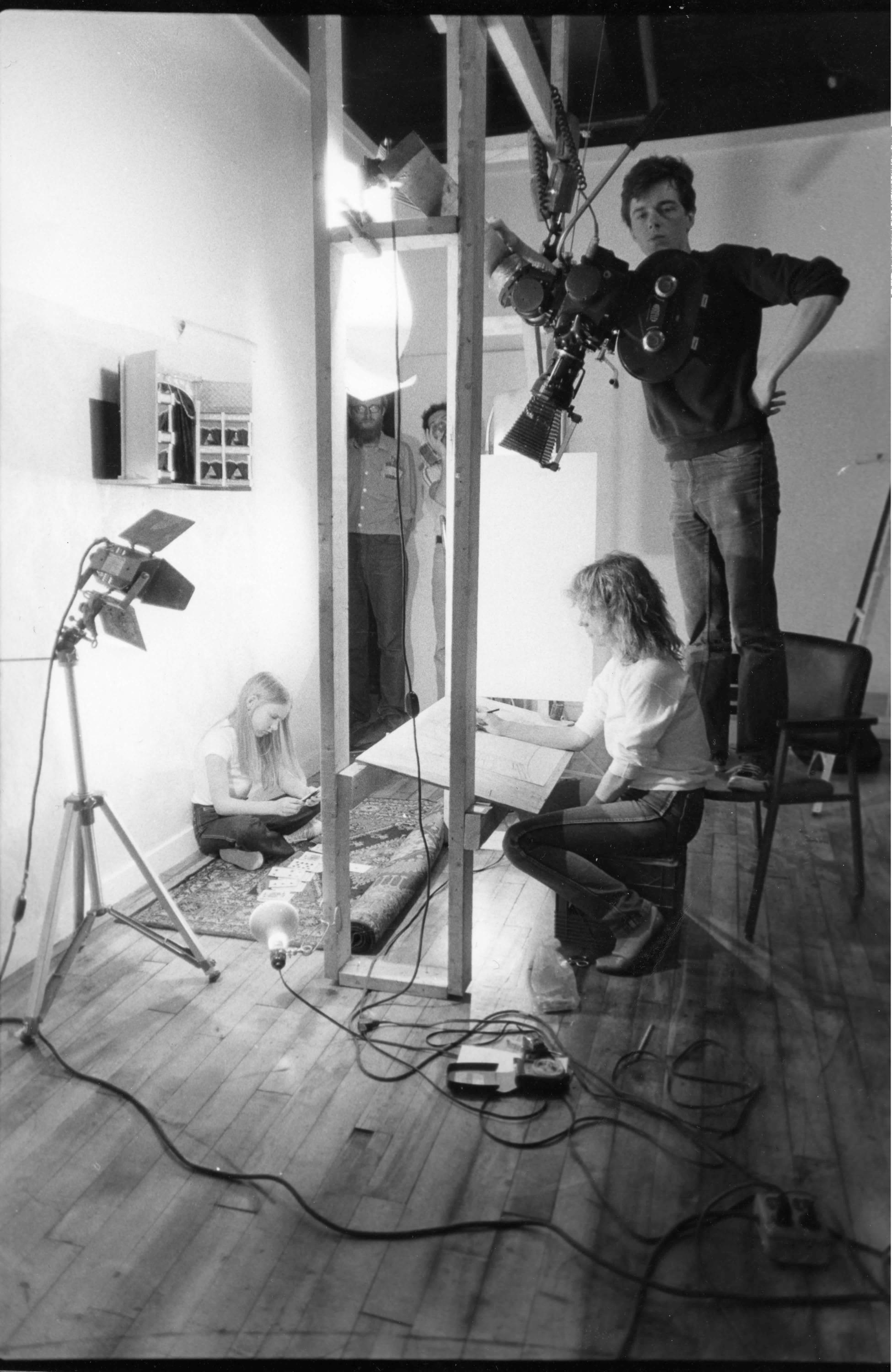

Shooting “Regards,” a film by Anna Gronau, at the Funnel

L-R: Amber Sansom, Villem Teder, Paul McGowan, Anna Gronau, Ross McLaren. Photo by John Porter

We were all reading Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1975); there was a huge amount of feminist film theory informing what people did. People like Anna Gronau, Judith Doyle and Michaelle McLean made analytical/structural films that were influenced by feminism. There were a number of aesthetic currents at work, and I think that’s what blew the collective up eventually. What was so fruitful in the Funnel’s heyday was the co-existence of all these different aesthetics. I loved the attractions of opposites. You had the tech boys, a homemade Super 8 ethos, an auteur 16mm tradition, and a strong core of Funnel members who were thinking about politics, feminism and race. The first structuralist-feminist work came out of the Funnel with Anna Gronau’s Regards (1983); a questioning of history and memory came out of the Funnel with Judith Doyle’s Private Property/Public History (1982); the first structural-experimental work that thought through race came out of the Funnel with Midi Onodera’s Ten Cents a Dance (Parallax) (1985). Midi’s film was a structural film, but it contained other elements as well. You could never call it fiction, but there were some people who said it wasn’t experimental. There were huge debates about what some of these films constituted. The discussions were productive, though finally the tensions around these positions, questions of what constituted experimental cinema, couldn’t be reconciled. There was a lot of pioneering work, and it’s hard to say that pioneering work has one aesthetic, because an aesthetic is related to canon formation, that’s how you identify it. I would argue against the idea that the Funnel had one commonly held aesthetic, though I know it was perceived from the outside as being low-budget, obscure, hardcore clubhouse.

A lot of the work was ground breaking, it was pushing the edge of what constituted experimental film, but it wasn’t framed that way inside the Funnel. Instead there was a lot of internal debate around whether it was really experimental or not. Instead of positioning the work as setting the agenda for a new discussion of experimental cinema, the points of view imploded, and the organization became less progressive and more conservative. By “conservative” I don’t mean politically conservative, but literally “to conserve.” The organization turned backwards to preserve older understandings of what experimental cinema was. I think some of the collective members wanted to go back to a world where they were the one avant-garde, making films and screening them for each other, with that this was enough to be artistically recognized down the road. I don’t know if everyone was in favour of the work around programming that David, Midi and I were doing. We were producing program series and catalogues that gave the organization a lot of energy and fiscal worth, which meant you could run things in a different way. But that may have been a direction that not everyone wanted. I see it as an ideological split. If people ask me what brought down The Funnel I would say the larger cultural shift from modernity to postmodernity. For me the Funnel as a collective project could not be sustained unless it was able to incorporate this shift, which would have meant that its founding ethos would have to move away from a modernist, structuralist paradigm to accepting experimental narrative, feminism, and more overtly political points of view.

Mike: Do you remember being approached by Vtape or any of the video organizations in town to screen work at The Funnel?

Dot: No, Vtape had A Space. There was a huge ideological split between the video and film communities. We were shunned by the video community because of the censorship issue. Remember, The Funnel was involved in an exhausting struggle against the Censor Board. That’s another thing that burnt people out completely. When you think of the level of devotion the Funnel entailed, it’s something you can only do when you’re in your early twenties.

Mike: Was the reaction shot to the Censor Board the biggest division between the film and video community?

Dot: It was pretty defining; it was huge. And yet, we ran a theatre and a gallery. It was a very different ethos than the A Space/Vtape crowd. They were very clearly defined entities. I don’t think you could belong to both, you had to throw your lot in with one or the other.

Mike: Does it seem unusual that the video community supported so many artists working on social justice issues?

Dot: No, because video in part comes out of the guerilla TV movement, it always had a social dimension. It has its Nam June Paik beginnings, but fundamentally it always had a community ethos. It was really a postmodern medium, whereas The Funnel was still showing Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (1902).

What made The Funnel different than video art, which was a new art form, was that there was an intergenerational sensibility. This was an avant-garde continuing in an avant-garde tradition and Canada had a great role in this lineage. I think that was important. Did people like Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland, both members of The Funnel, set the agenda? No. But they were supportive. They weren’t influential but they were elders, people to look up to. They made fabulous films, they were famous. Did they set the tone of the place? No. That emerged from the collective relational ethos of the people working there.

There was a lot of volunteer labour, but that was also common in the early music scene, the gay scene, the Body Politic newspaper, and the artist-run centres. It was the way collectives formed and exhibited. It had a lot to do with the fact that rents were cheap, we all had big studios, and you could live on relatively little money. I had jobs working in the ex-psychiatric world of Queen Street, drop-in centres, community centres. You would think that would be phenomenally exhausting. It was intense, but the world moved a lot slower then. There was no email or Internet. You wrote letters and they came back three weeks later. I made eight hundred dollars a month, and I never remember feeling short of money or time.

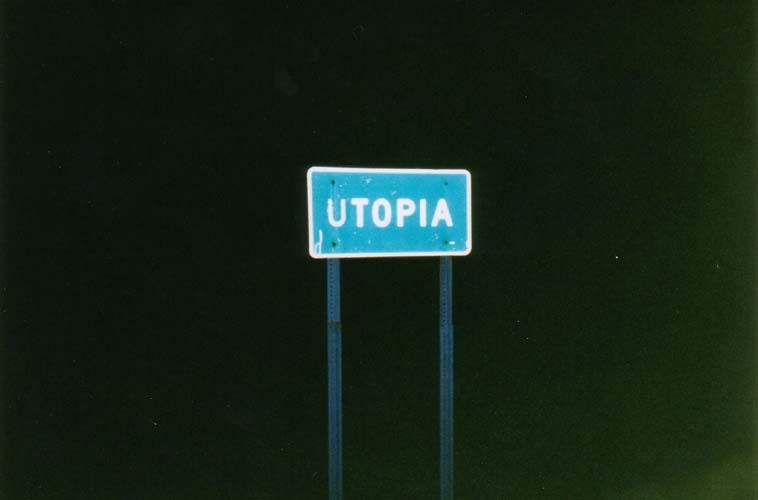

The alternative art world ran on volunteer labour, but when people believe in something it doesn’t feel like work. I still think of The Funnel as embracing a modernist structure of utopian dreams that doesn’t exist in the same way today. When I teach my students about revolutionary avant-gardes they’re incredibly puzzled. They don’t understand why people might work eighteen hours a day on revolutionary art without getting paid. At the Funnel, there was a collective purpose where one put all of one’s time and energy. It was a context for meeting people around the world and a way of making work and way of living.

Most of my students were born at the end of the bi-polar economic and ideological world. They’ve only ever known global capitalism, they’ve never lived within a dialectical sense of the world, that one could create networks outside of dominant technologies. The Funnel imagined a space outside of late capitalism. We had a shared mission in constructing an alternative universe. For us that alternative universe was The Funnel, for other people it was A Space, or the indie music scene. There was a sense that you could construct value outside of Bay Street, of whatever everyone else was doing to make money. There was still a notion that art could live outside of an economic system, outside of the capitalist script for living.

In 1983 Frederic Jameson wrote an article called Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, which he begins by saying: this is the end of history, of ideology, of art. Then he goes on to talk about how there’s no more outside, there’s only ever an inside. His articulation of a cultural logic came out of Marxism on the one hand, and mass consumer culture of the United States on the other. We didn’t think about either of those worlds. We lived in a world where you watched avant-garde cinema, where you believed in art, where it was enough to have a community and think about ideas. It was almost a salon culture. I always think about literary magazines from the 1920s. They might have had a readership of a hundred people, but some of the writers, like Jorge Luis Borges, are the most famous authors in the world today. These were precedents that made you believe that it didn’t matter if you had a huge audience, what mattered is that collectively you were creating new versions of the avant-garde for history in the future.

One of the distinguishing fault lines about whether you were part of The Funnel ethos or not was whether you aspired to make a commercial film. If you made a commercial film that was like joining the counter-revolution. If you moved to 35mm, or worked with the industry, or you wanted to show on TV, you were giving into the demands of popular culture. There was a huge split between high art and popular culture.

Mike: And politics?

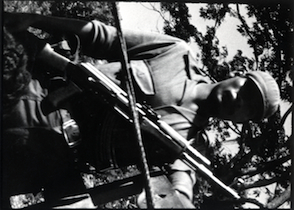

Dot: There was an unconscious anarchism that was associated with The Funnel, and certain individuals were politically engaged though most were not. Judith Doyle went to Nicaragua, I went to Nicaragua, Anna and Michaelle were very interested in feminism. I was writing a lot about psychoanalytical feminism and cinema.

Mike: Did the trips to Nicaragua, or feminist experimentalisms or queer representations threaten the group?

Dot: Absolutely. The group project was about making experimental cinema and individual expression, not about art as a political or social tool. It’s not like we were a group that collectively thought about Marxism and cinema, or feminism and cinema. It wasn’t England. People were in conversation, and made films influenced by some of these ideas but not everyone was reading Screen Magazine. Some people were thinking about how to rebuild a sound system from scratch, or how to upgrade the optical printer and not much else. And that’s what I meant by saying it was so interesting, because the project accommodated such diverse energies, yet at the same time the heart of the Funnel was the idea of a modernist avant-garde in art, of which experimental cinema was part of a long honoured tradition. When I teach the history of New Media Art I teach the cinema of the twenties, and then I make them watch Wavelength (1967) on 16mm film because none of the students today know what a film looks like. There was a materiality to the Funnel that was so different from video art’s signals and television sets then, or digital files today.

Mike: When the Funnel was alive film gear was expensive and required collective ownership. The tools were also the basis of potential communities.

Dot: In those days what held collectives together was the necessity to share resources because you couldn’t do it on your own, it’s the opposite of what happens now. Everyone has postproduction tools on their computer and a video camera in a cellphone that are way more sophisticated and accessible than could ever have been imagined thirty years ago. Today funding is hard to come by. Then, the Canada Council was funding new organizations, even if reluctantly in the Funnel’s case. The Funnel was always fighting for its little piece of the production pie, because we were perceived differently than more traditional co-ops. I think we didn’t do badly. There were people at the Canada Council who wanted production, programming, and distribution separated. The Funnel did all three, we had a vertically integrated structure. Making and screening films led to discussions and a conceptual framework, and that’s what made the Funnel a community as well as an entity. If you look today at Trinity Square Video or LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto), people come and go, make their work and leave, occasionally there are screenings. There’s not an identifiable core group like The Funnel had. The glue that held us together was funding, shared resources, and a vertical integration of all aspects of what one did with film.

When I became involved with the Funnel, I was given the impression that its relational structures were cemented around the building of the theatre and production spaces. That’s the story I heard from historical figures like Adam Swica, Ross McLaren or Jim Anderson. It was a mythic, and often repeated, tale of a heroic moment that united the founding members. I had already left the Funnel by 1988 when there was a decision to move. It’s as if they tried to relive that heroic moment by building another theatre in the belief that would bring everyone back together again. But of course it was a different historical moment in terms of people’s ability to volunteer time, funding structures, a decimated membership, and the rise of postmodernity that challenged the notion of what some would say was an insular notion of the avant-garde.

Mike: Many felt the Funnel was run by an inner sanctum, that all members were not created equally. The heroic building moment you describe was one marker of the true faith. Others might attend every gathering, but never find the door fully opened.

Dot: I was one of the chosen ones, adopted if you will, perhaps they thought I had useful skills. The first writing on film I did was for The Funnel’s newsletter and then I started publishing in the art magazine Vanguard, where no one else was reviewing experimental cinema. I became a kind of voice for the Funnel. Within a year of arriving I was chair of the board but I presided over the good days, not the bad days. I was no longer on the board or a member when the Funnel fell to pieces. Yes, there was a widespread sense of being excluded, but I felt part of the inner sanctum. There was a history I didn’t share but I didn’t feel like an outsider. Not everyone was adopted so readily. Some people tried to be part of the Funnel “family” for years but their adoption papers never came through. I can think of two or three people who came all the time but were treated with suspicion rather than welcomed. You also have to remember that I landed from Mars, that’s how people described me. I didn’t go to art school, I didn’t know anybody, I had no former allegiances, I wasn’t taught by anybody, I just showed up. My artistic formation occurred on the ground at The Funnel. I was an early adoption, and they’re always better.

Mike: The Funnel’s ambitious screening program brought in so many guests but they were often met with silence. When you arrived it was relieving for me because you asked questions.

Dot: I felt like I was in charge of asking the questions. I had my role. If questions were being asked they often sounded like this: in the third frame of the seventh minute were you using a red or a green filter on your camera? On the other hand, if everyone asked questions like mine it would have felt like a classroom. I didn’t mind the disjunctures but it was good I was there, I engaged people on an intellectual level that was lacking at the Funnel. People who prided themselves on their theoretical or intellectual frameworks saw the Funnel as anti-intellectual. I had lots of friends who asked: why are you there? It’s not theoretical enough. But some of these same people couldn’t understand why I worked in the field, on the ground, running community centres in Parkdale. I like the ground, I enjoy different perspectives. As Donna Haraway writes about her famous A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), I am searching for affinities and diversities, not cohesion. In a different context, Susan Buck-Morss writes about how the co-existence of different modes of radical vision was essential to formation of the Soviet avant-garde.

The Funnel came into being at the tail end of the Clement Greenburg days, when artists were seen but not heard. Maybe that disqualified me as an artist, I don’t know. People were very encouraging about the films I made. Very encouraging. But filmmaking for me was a collective experience so when the Funnel ended I never made a film again.

The legacy of this collective experience is very interesting, I’ve thought about it a lot. I’m not sure that what came out of the Funnel was of lasting cinematic significance. (Much of the work was lost or withdrawn from distribution). It was an interesting paradox. What held the group together was a notion of auteur-driven, experimental cinema, yet there was such a collective ethos that there were really no filmmakers. (laughs) Maybe the Funnel itself was our auteur project.

Because of the Funnel’s vertical integration I found its collective ethos very appealing. I wrote catalogues, curated, sat on the board, and made films. For me it was a holistic project. I certainly had some talent as a cinematographer, but lacked training. Film is a very technical medium. If I was really serious about making films I would have had to go back to school and train. Filmmaking wasn’t where I put my primary energy, and I wasn’t alone in this, which suggests that the holistic project of the Funnel was more important than the individual pieces, i.e., whether you were going to make great films or not didn’t matter. It was a very curious combination or coalescing of elements. I don’t know what other people’s motivations and dreams were. Maybe people joined because they thought that this is where they were going to become great filmmakers. I saw filmmaking as only one aspect of the Funnel community.

Mike: Could you talk about the French filmmakers Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki who showed movies and offered a workshop at The Funnel at your invitation in 1985?

Dot: We had a programming collective of six people. You didn’t come into the Funnel and announce, “I have an idea,” you brought it to the committee that collectively decided how many catalogues we would do, and what kind of programming would happen. Kathy Elder did a historical series at least once a week, other nights were reserved for Funnel members, then there was programming by committee. The staff worked in conjunction with the committee, and in those days the director was David McIntosh. He was succeeded by John Porter and tensions increased. John was perhaps a bit narrow in his focus. The directorships of Anna, Michaelle and David were times of expansion and vision.

In terms of Maria and Katerina, I flew to Paris to visit friends and while I was there I met with them to ask if they would come to the Funnel to do a series of screenings and film workshop (Portraits of Women). When they realized I was organizing this programming event as a volunteer, and that the Funnel was doing everything on a volunteer basis, they become passionately engaged. At the time they were representative of a French feminist avant-garde cinema that drew on the writings of Luce Irigary and Monique Wittig. These authors were also very influential in Quebec’s experimental feminist writing scene. Katerina and Maria made lyrical and visually intense films about women, nature and ceremonies. Of course they also brought sexuality in, but not via identity politics, which is how sexuality was approached by the Toronto’s media art scene, but from a French psychoanalytic and avant-garde tradition.

The two artists were here for about ten days and did a weekend workshop and screened their lyrical films. During their women-only workshop we made a wonderful film that was lost, it wound up in Gary McLaren’s apartment, and I don’t know what’s happened to it. Katarina and Maria felt they were the filmmakers, and that we were the participants, and they wanted to take the film back to France with them. We said no, this is the collective property of the Funnel. What a mistake that was. I feel badly about this because otherwise the film would still exist.

1985 was the pinnacle of programming. The Funnel had never done anything as ambitious before. We invited so many international artists. We produced four catalogues that year. I did two of the four catalogues, Cache du Cinema and Portraits of Women. Cache du Cinema was about going out into the local community to sleuth and showcase local work. Portraits of Women was about bringing French feminist experimental cinema into dialogue with local feminisms.

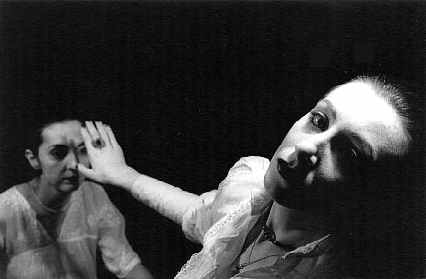

Elia Akrivou and Katerina Thomadaki in Unheimlich I: Dialogue Secret

by Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki

Mike: After David McIntosh stepped down as director in 1986, John Porter was hired.

Dot: There was a lot of pressure for me to apply for the position. I probably should have considered it but I had received a Canada Council grant, and technically you couldn’t hold a grant and work at the same time. I wasn’t going to give up that grant for the Funnel, but perhaps I could have negotiated something and I didn’t. I regret that because I think the future of the Funnel would have been very different if I had become the director instead of John. I remember Ross being very perturbed by John’s candidacy, but I don’t think there was anyone else who came forward. Ross was on the hiring committee as I remember.

Mike: The Funnel had three staff positions: director, office manager and equipment manager. The director typically did the programming and wrote the grants.

Dot: As the director of the Funnel when I was most involved, David McIntosh presided over the programming committee. If you were a certain kind of director you could steer the committee your way. But John didn’t have those directorial skills.

Mike: In 1986 a botched Toronto Arts Council grant and general grant writing difficulties led to another administrative shift at The Funnel. After five months, John’s job was split into two, he became the programmer, and Melinda Rooke was hired as the finance person.

Dot: By that point I wasn’t involved with programming at the same level as I had been with David McIntosh. Hiring Melinda Rooke was a huge mistake because she didn’t have the collective interests of the institution in mind. She didn’t care about art; she was a bookkeeper. And secondly, the advice she gave them was terrible. She told them: overspend and you’ll get bailed out. What sane accountant gives advice like this? An accountant’s role is to say no, you must stick to the budget. It’s the director’s role and the collective’s role to be visionary and tromp off like Don Quixote tilting at windmills. It’s never the accountant’s job to recommend reckless financial spending, which is precisely what I heard she did. Even before the move she wanted to expand within the building itself. There were two reasons why I left the Funnel. The first was the refusal to open up the membership and secondly I felt uneasy remaining on a board where Melinda Rooke had so much power. I felt she was leading the institution astray and I didn’t agree with the overspending.

Mike: In August 1986 the landlord asked for a forty-five percent rent increase, from $10,800 to $15,600 annually. In response, there was a proposal to expand facilities and occupy even more space, while at the same time a search began for a new location. Do you think the consequences of overspending and the state of the finances were widely understood by the membership?

Dot: I was able to figure it out, that’s why I left the board. I was in complete disagreement. I told people she was giving them bad advice but I don’t think anyone listened. I think they were naïve and wanted to relive the heroic days when building a space equaled a future for the Funnel. A lot of people walked because of what was going on, while others refused to acknowledge that Melinda was spending money we didn’t have. I remember feeling upset with Mikki Fontana and David Bennell about their intransigence around this issue. These were people who didn’t even make films, they had the least practice, and they were now attempting to control the organization when people who actually had a profile in the community like myself or Anna, weren’t being listened to.

Mike: Many people told me that the Funnel ended for them at the annual general meeting in October, 1986. There were approximately thirty full members, a third of whom sat on the board in any given year. Many had to be begged to join the board that year because of burn out. You made a modest motion for associate members to be allowed to vote for the election of full members to the board.

Dot: That is technically correct. But by implication my motion opened the floodgates to accepting more associate members as part of the core Funnel group, as associate members would presumably vote for full members who would support their joining the collective. From my perspective, the Funnel ended because it refused to open it up. It had run its course as a closed collective. There were a lot of committed associate members like Annette (Mangaard) who were not being asked by the Funnel group to become full members, who were not being adopted. The Funnel has adopted me, but such adoptions were rare. I was one of very few people who had not been part of the Funnel’s founding history who had been brought into the full membership category, and you can’t run an organization like that. These energies are centrifugal. Over the years I’ve been in different groups and they always end the same way. People refuse to open the group up, because opening it up means new ideas and change. But if groups don’t have new ideas and change they atrophy. I had felt the need for a couple of years to have more voices at the table. Maybe if we had more voices then John wouldn’t have been the only option for director.

Edie Steiner, Jim Anderson, Dot Tuer, and John Porter

in John Porter’s apt on 11 Dunbar Road, March 17, 1989. Photo by John Porter

There were a series of circumstances that led to The Funnel’s closing. The number of full member volunteers and their energy were ebbing, while at the same time there were artists producing really great work who wanted to become more involved. How did you become a full member? The closed group had to vote you in. C’mon. A lot of our volunteer labour was coming from associates at that point, they were doing almost as much work as full members, couldn’t we at least let them vote? Yet such a proposition was seen as far too radical by the historical figures. That’s when I became un-adopted. I was a full board member with quite a bit of authority, but every person who had been there from the Funnel’s beginning voted against it. Every single one. They saw opening the organization as a threat to its fundamental ethos and voted for the status quo.

Mike: Funnel founder Ross McLaren described it as a coup attempt.

Dot: The discourse around the motion to allow associate members to vote shocked me at the meeting, it never occurred to me that there would be resistance. Though it is also true that I didn’t lobby Ross ahead of time to support the motion because I knew he was dead set against allowing anyone in as a full member that he didn’t personally control the vetting of. So of-course he would see it as a coup. But it was no surprise. I had been raising the issue of expanding voting rights at the Board level for more than a year. I felt very strongly that the Funnel’s survival depended on its opening up. I guess the majority (of full members) felt equally strongly that their survival depended on keeping it closed.

I had been the special adoption, but I didn’t think this was the way the organization could thrive. If Ross saw it as a coup attempt, then perhaps the motion had to fail, because coups are always bad. Or are they? Ross’s arguments were so appalling I don’t think I ever talked to him again. I was so shocked at what came out of his mouth. It was basically the totalitarian notion that people shouldn’t be allowed to vote because people are stupid. I don’t agree. Artists didn’t renew their membership because they already felt excluded, that’s why I brought the motion to the annual meeting. There were a lot of people who weren’t going to renew their membership unless they felt there was a more inclusionary structure.

Mike: Do you know how Ross’s brother Gary McLaren got hired and eventually became the director?

Dot: Talk about atrophy. We’re not only going to refuse associate members the vote, now we’re only going to have family relations running the place, along with David Bennell’s friend Melinda Rooke who had no business being there. At the time it was heartbreaking and a lot of us were upset. When the motion was forwarded, I wish there had been a tape recorder because the discourse was so venomous, accusatory and defamatory that there was no going back. The old guard said such horrible things: you’re interlopers, it’s a coup, how dare you, you ingratiates, you bad adopted children. It was the ugliness of that meeting that drove people away. I couldn’t work anymore with those who remained, who wanted to preserve the Funnel as their private clubhouse forever. I didn’t want to be part of an organization that was becoming more and more myopic and closed. Also, whether closed or not closed as an organizational structure, the Funnel board should have fired Melinda before they fired anyone else. Instead, they fired John Porter who had supported the motion. The old guard who remained didn’t know how to run an organization. You don’t hire Melinda, you hire someone who has an investment in the art world and the experimental film community, like myself or Midi Onodera. You hire up, right? You don’t hire someone peripheral to the milieu because that’s not going to give the Canada Council any confidence.

Organizations go through tough times. When I was Chair of the Board of Fuse Magazine we retired a $30,000 deficit by going to ground. Everyone worked for nothing for a year and we got the magazine back on track. But you have to act. You don’t expand, you go to ground, you cut back, you cancel your long distance phone plan. That’s how you deal with the fiscal nightmares that arise in almost every institution. You don’t expand in those circumstances.

Mike: Some left the Funnel because they were burned out from overwork, including some of its most important members.

Dot: (Former directors) Michaelle McLean and Anna Gronau were burnt out, and there were other circumstances around Anna’s leaving that will always be left unsaid. Real history is always left unsaid, it is never written. My partner Alberto Gomez joined the Juventud Peronista, part of a larger urban guerilla movement in Argentina, when he was fifteen. Many years later, he was commissioned by Sylvère Lotringer to write a book about his experiences for Semiotexte’s Foreign Agent Series in the 1990s. When he had almost finished writing the book, Alberto told me: this book reads really naively because I can’t tell most of the story, there are so many things that can’t be said and people who cannot be named. I told him that if he felt people needed to be protected and their stories can’t be told, he should wait on publishing it. Wrong advice. He should have published it at the time because history is always partial. Now he’s working at a very senior national level of government and says, “No one will ever know the real history, ever.” Of course this has made me wonder why I did a PhD in history because history can never be known, it’s always part speculation, part fiction. The best you can do is craft a story shaped from documents and people’s memories, or what they are willing to tell you, at least that’s what I figure.