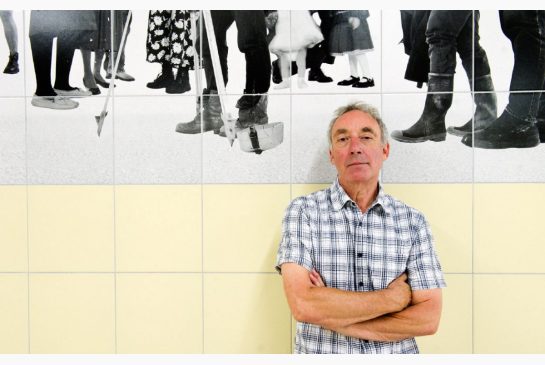

The Last Revolutionary Space: an interview with Eldon Garnet (December 2013)

Mike: Were you ever at CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication)?

Eldon: Oh yes. I knew (CEAC director) Amerigo Marras when he lived in Kensington Market and ran the Kensington Arts Association from his house. He was newly arrived in Canada and interested in architecture. The KAA moved to John Street where it was renamed CEAC. Diane Boadway curated one of my films for an exhibition in March 1976. I was living on St. Patrick Street, next door to the Music Gallery in a building that’s no longer there. There was a vacant lot between the two buildings and I remember going into that lot with my super 8 camera and turning circles, creating this structuralist piece called Container Contained (15 minute loop, 1976). I had bought a huge machine that took an eighteen-inch wide cassette that looped super 8 film and projected it onto a small screen. I brought the machine to CEAC but it wouldn’t fit through the door, so I left it there. We couldn’t use the machine, so Diane put a projector on the ground of the gallery and projected the film loop onto a wall. Someone from the National Film Board was in the audience and remarked, “This isn’t even a movie.” I took that as a mark of the screening’s success.

Mike: Did you ever see fringe movies at the Kensington Arts Association or in their John Street location where they were rebranded as CEAC?

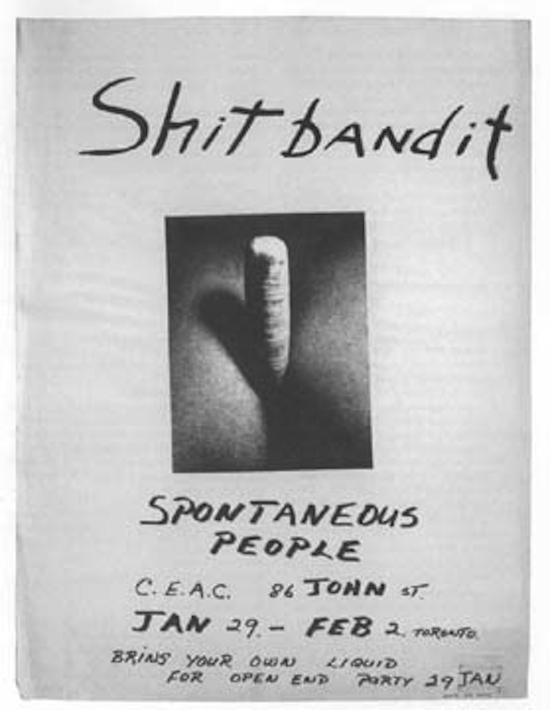

Eldon: Diane Boadway curated movies at CEAC as I mentioned, but what I remember were the performances. Ron Gii, who was called Ron Gillespie then, did performances called “Spontaneous People” with his Shitbandit group in January-February 1976. They were pretty scary, he was a great performer. It involved a lot of blood and screaming at the audience, sexual activity and throwing things at the audience. It was so intense that I remember slowly backing away.

John Street was CEAC’s best space. It was a long narrow building and they occupied two floors. The main floor was used for performance and group gatherings. The CEAC group were very open people.

Mike: What kind of art were you making?

Eldon: I was writing, making films, even performing. Though my performance career mercifully started and ended at A Space’s Nicholas Street location.

Mike: There was conflict between CEAC and A Space, do you know anything about that?

Eldon: A Space was very snobby, they ran a closed shop. I was a young artist and wasn’t allowed access to anything, the equipment was quite controlled and protected. If you wanted to use their video equipment, for example, you had to talk to the director. But they allowed performances, that was an area where they were really open.

My first show as an artist was at the Isaacs Gallery, and afterwards I realized I didn’t belong in that kind of commercial space so I went over to A Space and started showing there. I made interesting films and installations and off the wall performances with a group we called La Club Foot. We made up most of the dialogue and action as we went along.

Mike: CEAC was at John Street for just half a year in 1976 before moving to a four-storey warehouse on Duncan Street that they managed to buy with a Wintario grant.

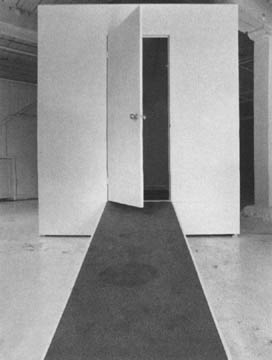

Eldon: That was a huge building with a lot of possibilities, but you have to remember, I’ve always been an outsider. I had a very close connection with CEAC, but I wasn’t their primary audience or as an artist a charter member of their group. They had their group, the insiders who went off to Europe and did performances together. I liked the basement at Duncan Street, I remember seeing Heather MacDonald’s environmental installation Rain Room there. It was a large cavernous room, like a house.

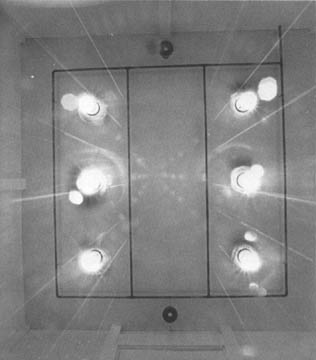

Mike: Rain Room was installed from September 18 1976 to October 30 1976. Dot Tuer wrote: “Rain Room was an 8 x 80 foot enclosed room with white sand on the floor, white walls, a grid of copper piping on the ceiling, heat lights, and speakers. Inside the room, it rained for two days, then heat lamps switched on for two days, causing a cycle of humidity that became dry heat and initiated the rain cycle again. The accompanying audio track juxtaposed the climatic changes with opposing sounds.” (Dot Tuer, “The CEAC was Banned in Canada: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” Mining the Media Archive (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005).

Eldon: I knew Heather and her suicide was quite a shock. In one of my early publications, the self portrait issue of Impulse Magazine, I published some of her work. She was one of the people I talked to when I went to CEAC. Her death affected me deeply. I remember teaching a class at OCA about death when I heard of her suicide for the first time. I was stunned and couldn’t go on with the class. I never understood her suicide, I understood that the AGO had seen Rain Room and were considering it for exhibition.

Mike: Do you remember any film screenings at CEAC’s Duncan Street location?

Eldon: Ross McLaren would have taken care of all that, but I never went.

Mike: How did you hear about the Funnel?

Eldon: My connection with the Funnel was through Ross McLaren. I got to know him on one of the Ontario College of Art’s annual bus trips to New York. There were seven busses and Ross and I were assigned to look after one of them which was a disaster. We were more trouble on the bus than the students. I think I was smoking marijuana when we were going across the border. That’s when I first met Ross, who was teaching at the college, like I was.

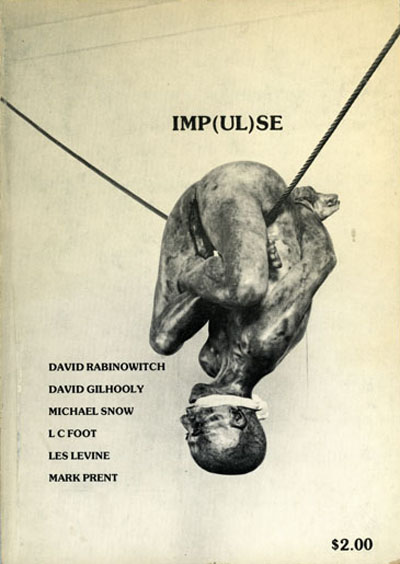

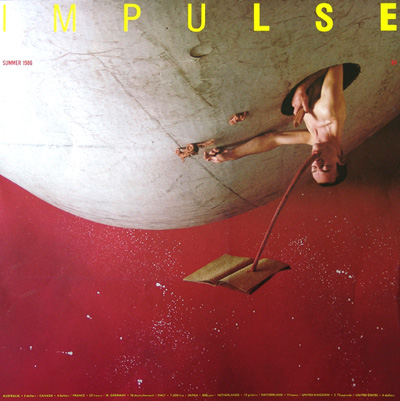

I had started a magazine called Impulse that was edited, designed and published by artists. In 1978 we held a dance contest in partnership with La Mamelle (an artist-run gallery) from San Francisco in the basement of A Space’s Nicholas Street location. We offered a hundred dollar prize for the best dancer. The next year I decided to do it more officially, and it became Impulse’s Second International Dance Competition. It was held at the Palais Royale because of the stories I had heard growing up about how my father had danced there with my mother. I thought it would be the best place to have a dance competition. It hadn’t been renovated yet, it was quite dilapidated but had a great sprung-wood dance floor. I asked Andy Warhol to come up to be a judge for the competition, but we couldn’t afford Andy’s fee so he sent Bob Colecello, the editor of Interview Magazine. I asked David Earle from the Toronto Dance Theatre to be a judge, and I was the third judge and MC. We offered a $500 cash prize. We had the band Johnny and the G-Rays, and John Cato play live. Ross McLaren was asked to make a super 8 documentary and I purposely asked him not to cater to any conventional documentary style, but to make a structuralist, broken up film that I titled Winning (40 minutes 2005). He showed it last year at 8 Fest, it’s a great movie, very jerky and sometimes out of sync. The sound system fucked up during the evening, it stopped all of a sudden while people were dancing. I can laugh at it now but it was very embarrassing at the time. The film has aged really well, you can see a slice of the Toronto art scene. The dancer who won was Krista, a tall beautiful woman who took off all her clothes and danced. Istvan Kantor eventually married her and they had three children together.

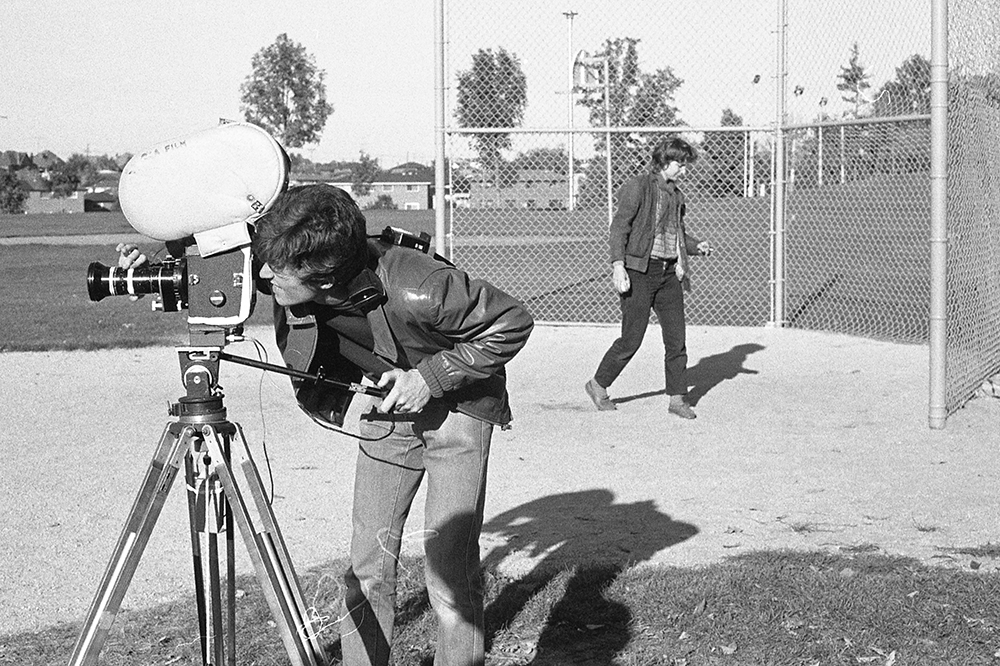

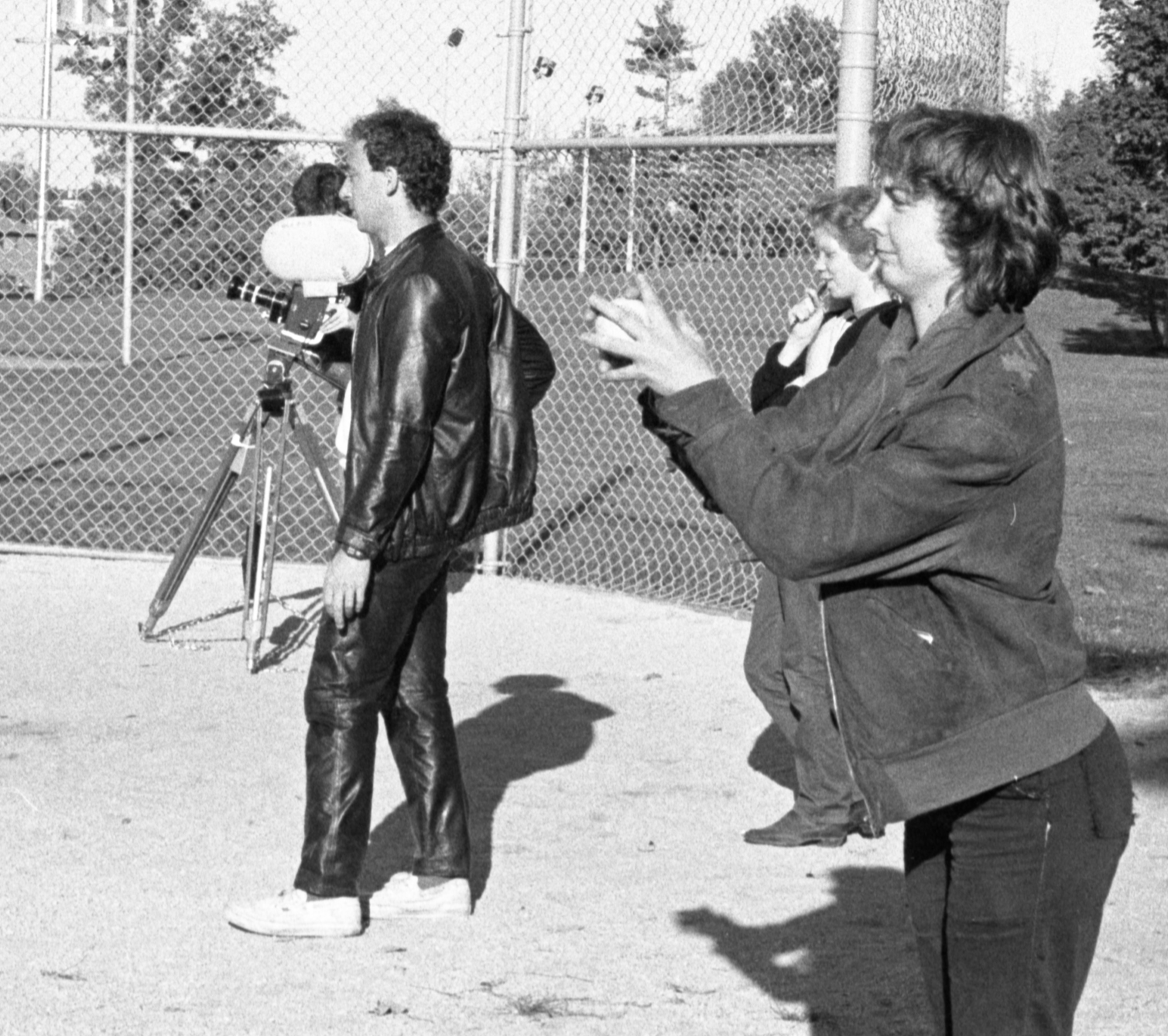

I started making movies when I was at university, though I don’t think I’m a particularly adept filmmaker. My first film was a University of Toronto centennial project in 1967. They announced a script contest, and that interested me as a young writer. I submitted a script and won so they gave me the money to produce a 16mm black and white movie. I didn’t know what I was doing, I had no idea. Luckily my brother’s partner was in the film business and involved with sound, so I used his equipment and learned how to do it. When I finished editing the film I didn’t ever want to do it again. Maybe that’s why I started going to the Funnel and working with Ross. We made a couple of movies together. The most involved was a 16mm movie called Political Error (12 minutes 1984) about young men playing dirt lot baseball. We had a voice over describing in structural terms how their interaction was politically in error. Ross and I still don’t know what the movie is about, but it’s pretty funny. Ross had a rear projection system, so we shot this academic analysis, performed by a guy in a suit with a pointer, in front of a baseball game, talking about why these junior players were politically incorrect in how they had structured their game. It was all scripted, I have no idea where the script is today. It’s very surreal. I am not sure why this movie was made. I think it might have been this pedagogical dream I had one night that wouldn’t let me go until it was given life as a film.

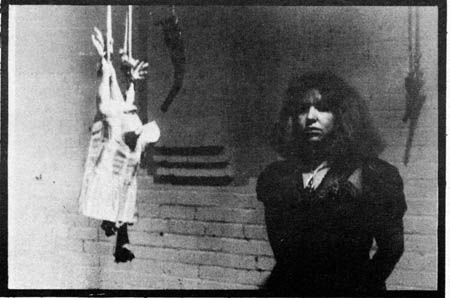

L-R: Eldon Garnet, Judith Doyle, Sharon Cook. Ross McLaren is behind the camera. Production stills for Eldon Garnet’s movie Political Error.

Mike: The Funnel’s Distribution Catalogue reads: “Political Error is a cultural political parody of didactic analysis of group dynamics employing a 1950s dirt lot baseball game as a central metaphor.” Ross helped shoot it, but it’s listed as your film.

Eldon: Yes, he shot and helped edit. We showed Political Error at the Funnel. But for me, the Funnel was a place where I could make super 8 movies, a format much more suited to an artist like myself. I started a series called Portraits (60 minutes, 1977-83) made with super 8 sound films. The rule was: Once I turned on the camera, I wouldn’t turn it off. Each portrait, each film, ran the length of a cartridge, approximately three minutes. I would ask people like yourself: would you like to do a super 8 portrait? What do you want to do? You would determine what happened, and I would document whatever you wanted to do in one take. One of the first portraits shows a headshot of Michael Snow making faces. Graham Coughtry ran around in a circle. They were all friends, I wouldn’t go to strangers, only people I knew. I made a new series every year for three or four years and showed them at the Funnel.

Mike: The Funnel’s Distribution Catalogue reads: “Portraits is a compilation of single-cartridge, uncut Super 8 rolls, each featuring a single artist, talking, mugging, acting or being him/herself. Individuals portrayed include Michael Snow, Graham Coughtry, Ann Milne, Joe Hall, Judith Doyle, Sylvon Britnell, Les Levine, Dennis Oppenheim, Arnaud Maggs, etc….” Would you show Portraits at the Funnel’s open screenings?

Eldon: I’m not sure, I think rather at a regular screening under my name. What I liked about the Funnel was the lack of audience. If you weren’t someone famous like Kenneth Anger you might have ten or twenty people in the audience so you could experiment. I probably didn’t do a lot of promotion, especially in those days. I didn’t give a shit whether anyone liked or disliked it, I was just making the film because I wanted to. The lack of audience freed me from the notion of criticality. That’s what I particularly liked.

I was never an official member of the Funnel, I never really joined anything. I think it was because I was doing my own thing, I was editing Impulse Magazine at the time so I had my own membership, my own club. What is the old Oscar Levant saying? I wouldn’t want to be a member of a club that would accept me as a member. It’s that horrible disease of avant-gardism, I had to be independent. I was always against joining. I don’t like 401 Richmond (a four storey warehouse building in downtown Toronto that houses A Space, Gallery 44, Vtape, CFMDC, YYZ, Prefix, Trinity Square Video, several movie fests, FADO, and more) because it’s too much of a club. I don’t like artists collectives. I like independence and remaining an outsider. But the Funnel allowed me to be an honorary member.

The Funnel had some equipment but I didn’t use it because I had my own camera. The Ontario College of Art had the best super-8 equipment, they were early supporters of the medium, they even had super 8 flatbeds. I’ve always taught there, I’ve taught there since I was born. Actually I started in my late twenties, it changed my position as an artist because I had a job. It was one day a week and it was the only job I have ever had.

Belonging to the Funnel didn’t compromise people’s work, but there was a clique there, it’s inevitable. There was a soft nepotism at work, a sincere lack of criticality about what your friends were making. If you were making straight documentaries I wonder what would happen to you at the Funnel. You probably wouldn’t have gone there in the first place, you probably would have gone to the National Film Board and received funding to make a documentary. I think the Funnel represented openness.

The Funnel was a machine for encouragement. I would make these super 8 portraits and know that I had a place to show them. Today, for example, as a writer you could write a groundbreaking novel and have nowhere to publish it, unless of course you’re a mediocre Canadian novelist writing in a conventional narrative style for Penguin or McClelland and Stewart. I have always had a problem with hierarchical systems of selection based on proven sales possibilities. I’ve never liked that. The Funnel represented just the opposite. Maybe because I was making movies with Ross, I wouldn’t have to ask for a show, I would just wonder out loud, “When are we going to show these?” That’s how a show would happen. There was no formal application process. Even A Space at the time had no formal application, you would ask someone, “Can I have a show here?” And they would reply, “When do you want to do it?”

Once a work is finished I don’t give a shit whether it has an audience. Someone else can worry about distribution. Rather, I am more interested in preserving and possessing the work. I have to admit, it’s an error for an artist, you have to let the market take your art away from you. But I want to possess my own work. My commercial dealer has trouble with that of course. “Why are you charging so much?” “Because I don’t want anybody to buy it.”

Mike: Did you go to the Funnel to see work?

Eldon: Yes, I would go maybe once a month, to see work by someone I knew.

Mike: Would you see the same people when you went, or were there always different people?

Eldon: A lot of the same people were often there, but you could also feel and see divisions in the community when you studied the audiences. When Bruce Elder showed his crowd would come. When he wasn’t showing he would talk from the floor and critique. As an artist I knew right away I’d rather be associated with the people like (Funnel directors) Anna Gronau and Ross than the Bruce Elder crowd who were over determined in their approach and subject material, trying too hard to be creative and poetic. They were too smooth and literally too intellectually conscious.

Mike: Was the film scene more divided than the art scene in Toronto?

Eldon: Art exists within a hierarchical system, certain people form clubs and as the scene grows there’s more divisions. I certainly experienced the film community’s divisions. I had no desire to be part of the “establishment experimental film scene” who were well granted to make films, while people at the Funnel rarely received money to make work. The artists I was interested in were independent, or at least appeared independent.

Mike: Do you think there was a Funnel aesthetic?

Eldon: The Funnel aesthetic could be described as a broken up structuralism. There was a lot of experimentation with form, content was secondary, film itself was the subject . You were experimenting to see how you could expand the territory. It might have some narrative qualities but that wasn’t a major concern. It was about a playful manipulation of the actual medium, film itself, the materiality. And it was done on the cheap, many people showed their originals. You can see this in the work of artists like John Porter, or Ross McLaren.

Mike: Sometimes Funnel group shows would screen in far away cities, were you ever included in those programs?

Eldon: They never packaged me in their travelling screenings. Here’s where your politics would have taken place, because I wasn’t part of the official Funnel membership, I wasn’t part of the group. But I didn’t care, I just liked making films. I used the Funnel to make and show films. When they were leaving on their big road trips I wasn’t jealous becauce I understood this was their entire career. I was an outsider because film was only one area of my production. It might be very modest of me to say, but I never considered myself a filmmaker.

Mike: Did you see movies at the Funnel that changed the way you thought about cinema?

Eldon: I grew up in Toronto and went to university here from 1966-1973. I learned about film at Cinecity, an independent movie theatre with a small screen that was at Yonge and Charles. I went there with friends to watch movies. That’s where I first saw Kenneth Anger and learned about experimental films, so by the time I got to the Funnel I knew how to be broken up, or how to make interesting, silly little movies.

Mike: There was a three-day event in August 1969 at Cinecity which showed Warhol for the first time in Toronto. Jonas Mekas came to present work and Joyce Wieland had an installation in the lobby. Did you attend that?

Eldon: I must have been there. Warhol’s two-screen Chelsea Girls (210 minutes 1966) made a big impression on me. They were ambient movies, you didn’t really have to pay attention. That’s what those kinds of movies taught me. You don’t have to watch it, it’s pretty boring, your whole attention doesn’t have to be focused on the film. You can be in the room while leaving the room. I presume it appealed to my attention deficit and general lack of patience. It’s like Mike Snow’s La Region Centrale (180 minutes, 1971). Do I have to sit and watch the whole thing? Well, maybe you do. When I first started making films I learned from direct cinema documentary filmmakers like D.A. Pennebaker who used a handheld camera and a portable sound recorder. That’s the kind of breakthough I was really coming from. By the time I came to the Funnel I was already conceptually developed as a filmmaker.

I made a super 8 narrative film called Einstein’s Joke (20 minutes 1978) with subtitles. The film enacts a joke which the filmmaker claims was a favourite of Einstein. Apparently he was fond of relating this joke at formal dinner parties, insisting on its profound philosophic meaning. In ‘German’ with English subtitles.” You could call this joke a fable. The film is an existential look at Einstein’s concept of relativity, the human aspect of his theory. Equality can only be judged by understanding the situation of the journey, the context of elements. In his book on relativity theory Einstein uses the metaphor of two trains travelling in the same direction at equal speed, side by side, making their relative speed zero. In its way Einstein’s Joke is about two individuals travelling together at the same velocity, events occur but nothing changes. In Einstein’s joke, there are two peasants travelling home, one has a cow, the other doesn’t. During their journey the peasant with the cow offers the other his cow if he will eat a live frog. The frog is eaten and the cow is exchanged. Later in the journey, the peasant with the cow, supposedly feeling remorse, makes the same offer to the other. The frog is again eaten, the cow exchanged. The two continue on as before complaining that their feet hurt. In the film, the frog is possibly a metaphor for time. The actors in the film are speaking a broken form of German. I know of no other super-8 film at the time that attempted to employ subtitles.

From the beginning the film was done to create a cinefiche. The cinefiche is not a spin off of the film but the core of its intent. The film and cinefiche was an issue of Impulse magazine, the last of this serial publication’s experiments with “container”; it followed a year or so after the release of an issue of Impulse as an LP. During that period, Impulse magazine took on various guises and disguises. For this issue I wanted to create a cinefiche. In place of a printed magazine, Impulse subscribers would receive a fiche, a four by six inch acetate card that showed subtitled frames from the film that could be read as a visual narrative. You had to take it to the library in order to view it on a microfiche reader. The arts councils, Canada and Ontario, who provided funds to Impulse were not too happy with this issue of the magazine, in fact, they saw it as an affront and cut off all of our funding. Luckily for the magazine, before their decision, I had decided to work on another experiment, the standardization of the format into the glossy square magazine which when sent to the councils restored their support and became what was generally recognized during the 80’s as Impulse magazine, the format most are familiar with.

I screened Einstein’s Joke as a movie at the New Yorker theatre here in Toronto, and at La Mamelle in San Francisco. It was a conceptual piece. Like the earlier Container Contained where I was running around a vacant lot with a camera, then trying to project it inside a machine, I was playing around, experimenting. There was a sense of pleasure at the Funnel, that filmmaking could be play. If people took it too seriously it became a parody of itself. When I look at the films that were unsuccessful, they were the ones that tried to be poetic, but most often instead became Hallmark calling card films. They took themselves too seriously. The people at the Funnel were anti-film, the Funnel would permit you to make anything you wanted. It didn’t have to be well done or well executed.

We were not aware at the time about post-structuralism. Those ideas of the French theorists didn’t have any impact on the artistic community until the late 70s and early 80s, so the key films at the Funnel were structuralist films. The people you would talk about would be Wittgenstein and Lévi-Strauss, you had a notion of order, which was contrasted with the artist’s tendency towards disorder, and that created an interesting tension.

Mike: Was the Funnel punk?

Eldon:.You could call some of the films punk, they were broken up and rough. They wanted to be unpolished, and they came from a DIY attitude. But you had to have a certain personality to be punk. I was never really a punk. The people at the Funnel were more meek than that. A good punk is very fuck you. I think CEAC was more punk. They were gay punk, whatever that means.

Mike: Do you know anything about the Funnel moving from its east end King Street location to Duncan Street, the heart of what used to be the Queen West art scene?

Eldon: When the Funnel announced their move I knew it was the end. It felt like they were trying to regroup but it didn’t work. You can tell when a move isn’t going the right way. For example, recently when Canada Post announced severe cuts to future mail delivery it was obvious something was ending, it wasn’t forward thinking but weak thinking. When the Funnel moved I wasn’t really involved, but I presumed the energy level would have been more than they could sustain. When the Funnel moved to King Street and built their first theatre it required a major collective force. When Impulse magazine moved from Richmond Street to Skey Lane in the mid 1980’s there was a huge collective energy. The building was a mess, it had been a stable and a furniture refinishing plant, people helped chip in to turn it into a space where you could produce a magazine. I don’t know if the Funnel had that kind of collective energy when they moved to Duncan Street. I felt they didn’t. But I had already withdrawn, I wasn’t making super 8 portraits any longer.

Mike: Is the collective energy attached to a utopian hope, a temporary dream of community?

Eldon: When you say utopian community you are implying an absence of hierarchy. But every organization needs a leader. Someone has to take on the responsibility for the project and at the same time become the hardest worker and go beyond what the individuals of the group think is possible, if they don’t, the project flounders. There is a hierarchy of work. The hardest worker becomes the de facto leader. You need someone in charge who has creative energy and a way of not dictating but simultaneously having the final voice. Collectivity often doesn’t work because eventually there are divisions. You need someone to heal the wounds of division by being the one who gets whipped the most, they’re the one taking the most shit, but they’re also the one making the final decision. It’s hard to describe. I’ve just watched my students trying to make a periodical but the ‘rulers’ aren’t there. The ones I thought would take charge backed off, so it’s gone. Unless you do it now, you lose your energy and your ability to create something fresh.

Mike: Were you surprised to hear the Funnel closed?

Eldon: I wasn’t surprised when the Funnel closed, CEAC was more of a surprise. CEAC’s closing was a failure of Toronto. The Funnel’s closing came from a lack of collective drive and purpose, super 8 was dead by then, video was taking over. Shooting super 8 today is unnecessary and expensive, it’s mannerist. I don’t think the Funnel was necessary any longer, it had lived out its mandate.

When CEAC closed they had done something that no other arts organization had managed, taken possession of their own building, and they had a strong political voice that was totally necessary. They were no different in their radicality than other groups in Europe. They were closed down because of Strike Magazine’s advocacy of revolutionary ideas, but they were just following Italian Autonomism, a movement that had very much influenced Amerigo. I thought it was amazing, the kinds of socio-political activity that was taken in so many different forms at CEAC, but they weren’t defended by the Toronto community who were afraid of them, and afraid of being sucked down the whirlpool of emptiness that CEAC had been drawn into by the House of Parliament and the RCMP. CEAC wasn’t defended properly, the Toronto arts community didn’t rally behind them. I felt betrayed by all the political leftists in the city. The artists who were doing Fuse Magazine should have rallied around them, but obviously they didn’t because they were afraid, self-serving. A Space should have rallied, but they didn’t, there was a general inability to react. CEAC was the last true revolutionary space. Their ideas, even their capitalist ideas, were brilliant. Buying your own building might have permitted them to be free of the arts councils that have produced so many tame organizations. Look at what has happened to A Space. It has no radicality. It’s the most tame space in the world. All those spaces in 401 Richmond lack urgency. If you are funded by Canada Council grants and Ontario Arts Council grants every year how can you do anything radical, you might disturb your benefactors. Today you are rewarded for mediocrity and compliance resulting in both a conscious and subconscious lack of ability to create new and difficult directions.