Power Of: an interview with Paul McGowan

Mike: How did you find your way to the Funnel?

Paul: I heard about the Funnel while working for Reg Hartt’s Cineforum as a projectionist in 1978. He was showing his collection of 16mm animations and rare shorts at Rochdale College. I just dropped in while the Funnel crew were building the theatre at King Street. I got involved at the start of renovations. The King Street (warehouse) space was essentially empty at that point. I believe the projection booth was roughed out. Building the theatre was essential to creating the group identity. Working together was actually fun and informal, as we all got pretty sweaty and dirty. I remember working with David Bennell and Tom Urquhart, building the risers for the first theater at 507 King Street East. David was the only real carpenter. He designed a jig to assemble the riser’s supports, so almost anyone could hammer them together. Tom and I had some experience roofing. We were both young, able, and had a good idea of what to do with a hammer. Consequently, we ended up spending a lot of time as David’s primary movers. I got my first introduction to drywall holding a sheet over my head in what would be the projection booth. As I recall, it was a cramped, backbreaking job I swore I’d never do again. A truly unfortunate introduction as it led to renovation and carpentry becoming much too big a part of my life. But I still have all my fingers and toes, so what the hell. Tom and David were great guys to work with — David had the carpentry knowledge and Tom brought enthusiasm.

The Funnel seemed like the right thing to do and I liked everyone there. It would be a theater focused on experimental art films, which I had real passion for, so it felt like a good fit. I had no expectations. I grew up in farm country, so that kind of communal work wasn’t uncommon back then…

As I recall the construction went on for a couple of months, the risers alone took a couple of weeks. The booth was complex — Villem Teder did the electronics and probably designed the layout with David. I recall putting drywall on the ceiling produced nasty, nightmare-screaming muscles. When we were finished or close to finishing, Ross McLaren asked if I was interested in joining the core group. We each put in ten dollars a month towards the rent which became the annual membership fee of $120. Each of us ran, or helped run, two shows a month. I usually ran the open screenings which happened once a month, and helped out with another screening. I did a fair bit of projection which could be a stressful job.

I liked the challenge of being at the open screenings — every imaginable kind of work came through the door. Most people were great to deal with, they were usually overjoyed to see their work on a good screen in a good space. People may not realize how difficult it was to get screened back then. Meeting the artists afterwards at the pub was very cool. We often went to the Dominion Tavern on Queen Street, a two minute walk away. Very old school. OMG the Dominion. We had a thousand great talks and after screening hang outs.

As regards eye burning work, there was a movie called Sides that was special, it was all shot sideways. It was made by a young woman who might have been from the Ontario College of Art. I think her name was Susan Reaney (or was it Lorna Mills?), and she went on to make a film that we (John Porter, Dot Tuer and I) programmed in a series called Cache du Cinema (April 1985).

Peter Chapman made a film called 1-51 that showed a loop of rising balloons that he had printed over and over again, the picture gained contrast until it became completely abstract. I saw it for the first time at an Open Screaming. Many of the films at the open screenings were shown there for the first time. Of course some didn’t work, but it was very popular. We showed lots of films.

Mike: Was there a “Funnel aesthetic,” a house style? Of course everyone made work in their own way, but did you feel there was a certain aesthetic sensibility that was shared (an interest in formalisms, a celebration of super 8 everythings, working without money…)?

Paul: Extremely low budgets were definitely something we had in common. The films of Andy Warhol and Michael Snow were influential, formalism was very important, and yet it was an artist’s culture not an academic one. I recall Keith Lock whose work had a natural narrative, he was very interested in formalism and minimalism; those aesthetics were what we as a group referred to, or maybe deferred to…

It was remarkable that the greater culture of the city took notice. The Globe and Mail in particular followed what was happening at the Funnel. Do you remember the name of the Globe’s art critic? It seemed to me he was everywhere on Queen Street. John Bentley Mays.

It’s just my opinion, but I think the fight with the Censor Board drove the Funnel into the limelight. I believe that what made “the Funnel: an experimental theater near you” was the desire for a good screening space free from the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op bullshit (where the administrator defrauded everyone and took the grant money). But the Censor Board found us and began a fight and very nearly took us down. No one felt we should be censored – it made no sense to censor art, so we fought.

Struggling against the Censor Board, I learned a great deal about how things worked. We had to deal with police, fire marshals, etc. The Funnel was instrumental in the anti-censorship fight. I believe as a result of this stance, inspectors were sent in, which resulted in a $35,000 upgrade in order to meet code as a theatrical venue. Drywall (5/8 inch, fire-resistant) needed to be applied to the entire interior of the theater. Steel doors and panic hardware were installed. This was accomplished by what started with a core group of forty people providing ten dollars a month to cover rent and expenses. It was mostly the same group that built the theatre who undertook the renovations. This was a freaking miracle and a huge turning point. Keep in mind this is my version of what went down. In my opinion, bureaucrats hated the Funnel’s punk rock, anarchistic guts. I happen to think it’s a very good thing to be hated by bureaucrats.

There was also the sense at first that we did not want to be dependent on grants or government support. That’s why initially the expenses were all born by the membership. Eventually that changed and the grants got bigger and you probably know what happened in the end. The renovation was a turning point for both good and bad. The Funnel had to become legitimate. Having fire doors and fireproof drywall and bringing the building up to code was good. And yet we had to raise money which meant grants so we were no longer “outlaws” so to speak. But keep in mind: we won the fight in the end. Mary Brown (head Censor) and the Board had to back down.

The Elementals. Paul McGowan, Ross McLaren, Edie Steiner in the Funnel theatre, 1983. Photo by John Porter

Mike: You were part of an experimentalist band called The Elementals that recorded at the Funnel during off hours.

Paul: Edie Steiner was involved, and John Porter hung out with us, at least that’s the image I get. I played bass, Ross was on guitar and Julie War (aka Edie) probably did vocals. I say probably as she was there and yet I can’t say for certain that she did. I’m three thousand miles and thirty years removed from those late nights. We made recordings at the Funnel including “Sweet Little 409” a Beach Boys song which might have received some airplay on a community station. The Funnel had a nice little Teac ¼ inch 8-track tape recorder which fit in with the “get the most bang for your buck” punk/anarchist aesthetic of the times. There was a good chance we recorded some other songs, I do know we made good use of the Teac for soundtracks. Dave Templeton and I recorded my song Cockroach Blood on another late night after everyone had gone home. We had a lot of fun at the Fun-nel, being creative. Creative energy drove the place, whether it was running open screenings or showing Andy Warhol movies or making installations in the gallery.

Digression: Villem Teder, who we referred to as a filmmaker’s filmmaker, was essential to the quality and clarity of the theater experience. He had a genius for technical design. The projection booth’s electronics were largely his doing. I remember being blown away by the simplicity of the speaker setup. I sold my film Why do You Want to Be Alive? (30 minutes 1982) to PBS because the super 8 projection and sound was near perfect. One of the reasons artists came to Toronto in the winter from all over the world was that there weren’t too many theaters that equalled the quality of the Funnel.

My friend Claude Theriot jumped off a sixth floor balcony early one morning. I went to high school with Claude. He was good musician, a fine guitar player and singer who co-wrote the music for my film Loose Ends. He was also a carpenter who worked with my dad to build a barn, and while doing so he became close to the rest of my family. I’d moved to Toronto and like most of my hometown cohort found somewhere new. After Claude died I came back for the wake and while sitting in a state of shock with my old friends who’d also found their way back I had an epiphany. I had a passionate need to make a film to answer the question: Why Remain Alive? I knew exactly what to do and how. My brothers and sisters, my family, needed an opportunity for catharsis. So I went to my family and asked each of them: Why Do You Want to Be Alive? That became the film – thirty minutes of unedited, passionate knowing that came from a place I can’t logically explain. I shot one roll of super-8 per sibling and parent, and they were assembled chronologically, entirely unedited. Work is passion.

I moved into the second floor of the warehouse on Parliament and Adelaide with John Porter and Jim Anderson around 1980. Dot Tuer spent a good deal of time there hanging out with Jim. Dot, Jim, John and I put together a film series called Cache du Cinema there. I include Jim even though he was not officially listed as a curator for the series because he always had an influence simply by being Jim Anderson. Jim and Keith Lock were a creative influence on the Funnel that shouldn’t be ignored – their consistently creative approach to life had an effect on a lot of people. The warehouse was a hangout for artists: FastWurms, Fifth Column, people who knew John. There were great parties: John created posters that we gave to Funnelites and others in the scene. We had no curfew as we were in a day worker neighborhood. We opened our studio areas which became impromptu installations. John set up a swing that became part of or inspiration for some of his moving camera work.

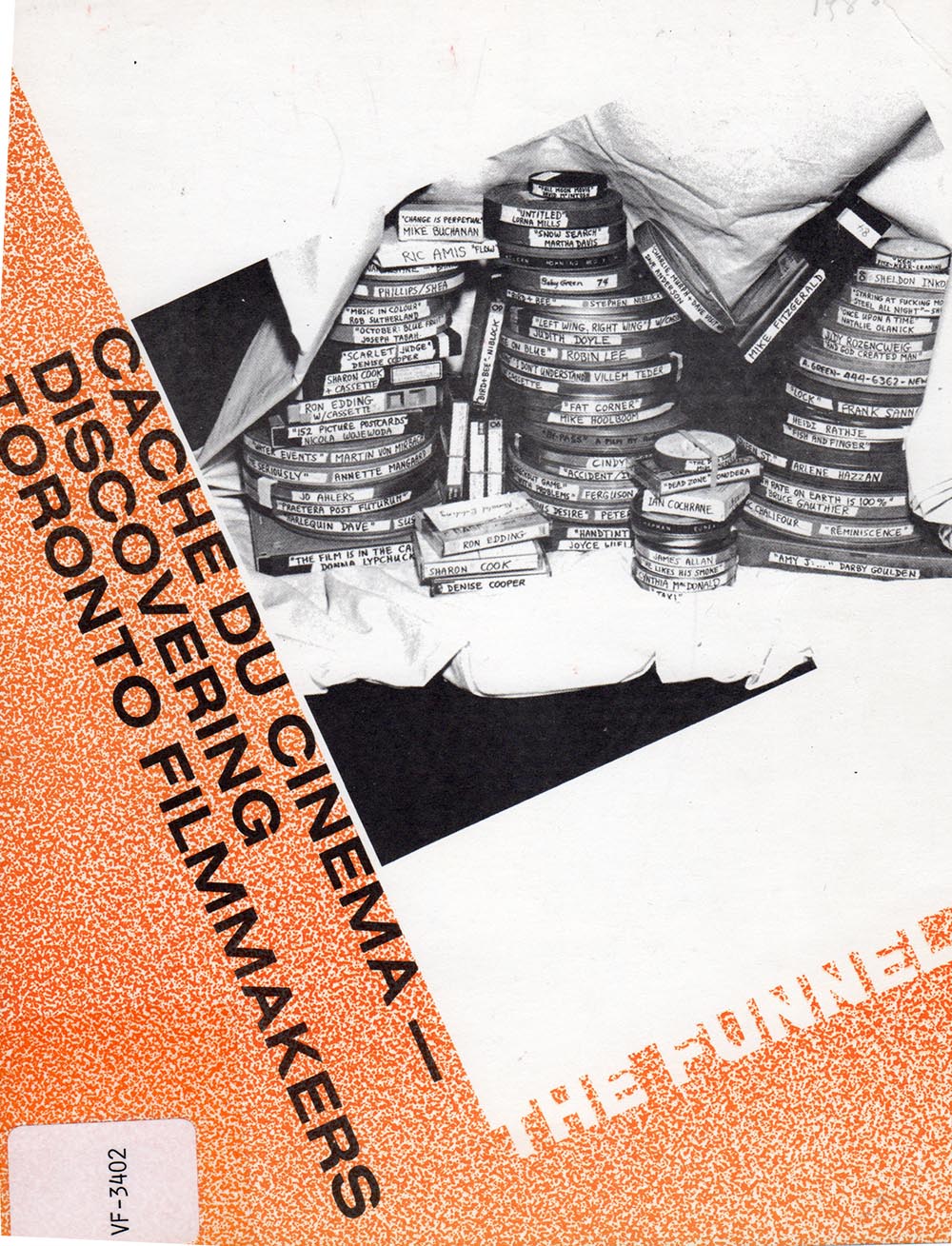

Mike: Cache du Cinema was a five-screening event of Toronto shorts held in January-February 1985, with an additional pair of screenings held in April of that year, with an accompanying catalogue. Dot Tuer, John Porter and you are listed as the curators. Every Funnel member showed their first movie, and lesser known or first time movie makers from Toronto were also invited. In the catalogue you wrote, “Art is a productive activity as opposed to a managerial activity. Management and government seems to be a matter of savoir faire. Those that have this savoir faire tend to inherit the understanding and connections (as well as the ability to sit at a desk for great lengths of time and push paper), the wherewithall to deny the productive drive inherent to the working class. So I believe this series is really only a small beginning, but a beginning, in the right direction providing support and access to local artists who are long overdue it. Who as a result of an almost Galahad-in-search-of-the-Grail obsession are barred from the mainstream of society and its technical and intellectual benefits.”

Paul: We had a good group that met over coffee or sometimes wine at the Incense Factory warehouse on Parliament. The floor was covered in a thick layer of incense left behind by Hare Krishnas who used the space to make incense. There were a lot of informal meetings over coffee when (Funnel members) Edie (Julie War) Steiner, Steve Niblock, etc. would hang out and discuss ways to make work happen, solve problems, or find inspirations. For example my cat Breakfast loved boxes and hanging out in the kitchen which inspired John’s film Tour of a Cat House (4 minutes 1982). The walk from the Funnel to the warehouse took less than ten minutes so artists would often visit before or after their show sometimes to smoke some pot or have a meal rather than drink at the Dominion.

The kitchen was large and a great informal space to hang out, so most of the meetings were there. We divvied up the curation according to our individual interests with the intention of finding new or hidden work. I was curious about student films which took me to end of semester screenings throughout the greater Toronto area. We designed the screenings to be diverse to bring in broad audience; keep in mind the purpose of the Funnel was to expose experimental/art film to as many eyeballs as possible. The screenings were, as I recall, all sellouts with enthusiastic audiences that stirred the pot so to speak. We wanted to shake things up, find new voices, and reach beyond the Queen Street enclave of artists. Nothing wrong with that scene, I was part of it at a really vital time yet artists can be territorial like any other kind of human. Queen West had great music: punk, punk country, you name it. I remember seeing Glen Branca at the Bamboo with twenty or so very loud guitars creating unearthly harmonics. And seeing too many artist collective shows to count – it was a truly vital time.

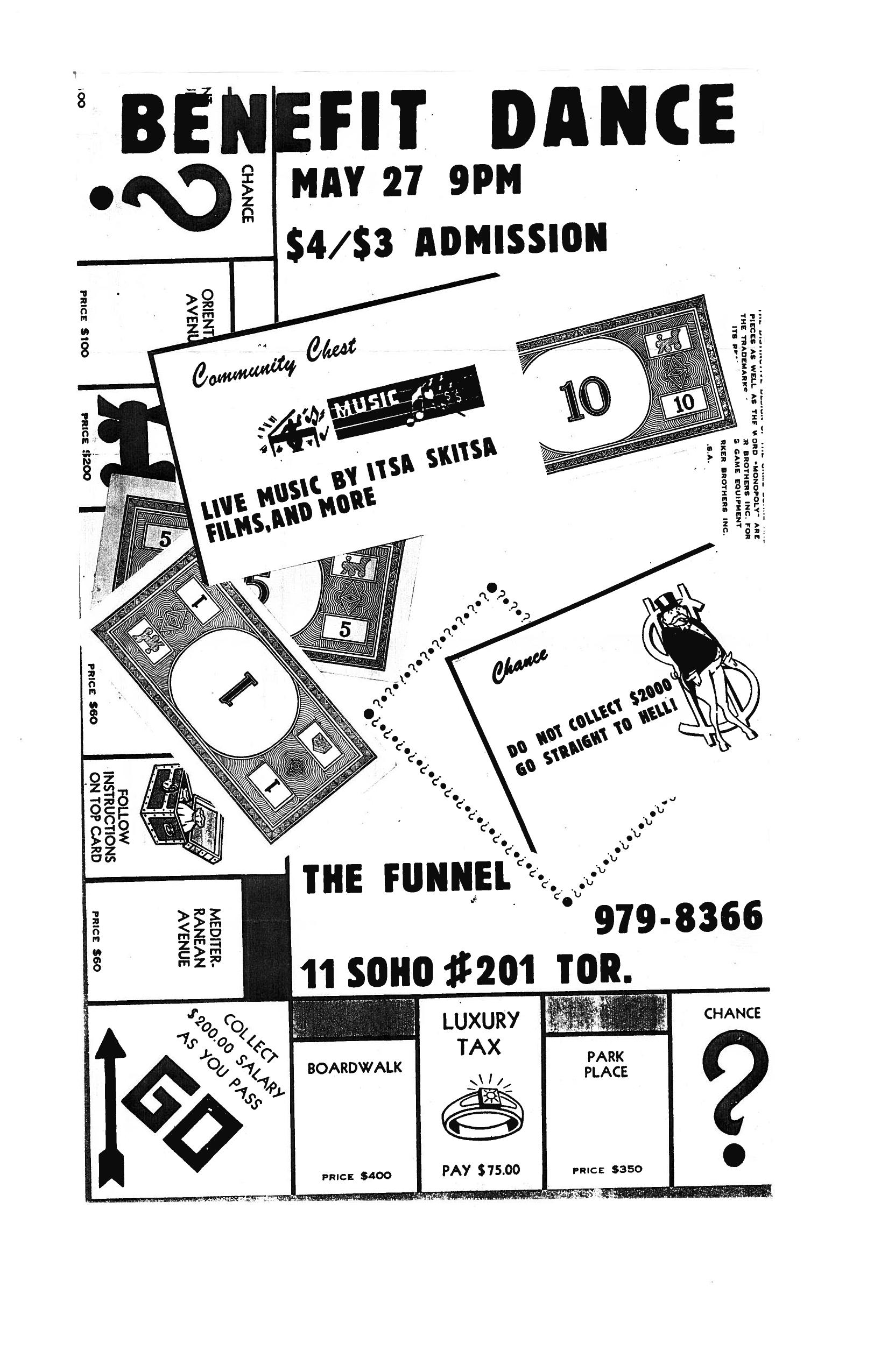

Mike: Can you talk about the Funnel’s move to Soho Street where the few remaining members built a theatre but the rent was too steep and the dream died?

Paul: I was there but not directly involved. I had refused to run for the board when asked, mostly due to abandonment issues which would be difficult to explain and utterly irrelevant. I don’t know if I’d been more mature at the time and run for the board whether I might have been the sort of influence to prevent what happened.

As I recall Ross McLaren and Anna Granau had run the office: they were responsible for writing the grants, dealing with the Censor Board as the films needed approval for public screenings (except for the open screenings — we screened what showed up and damn the torpedoes), licenses, taxes, all the paper any organization deals with. After ten years they were burnt out and we could now afford to hire management. So the Funnel: an Experimental Film Theater Near You brought in a former Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals manager. The beginning of the end arrived in a tweed skirt. She was a nice lady who loved animals and carried a streak of megalomania (in my opinion – I’ve been wrong before). There were a number of us who didn’t like the idea of bureaucracy being part of a punk/anarchist-era arts collective. It turns out we were right – and a lot of good that did us. Did I mention this is only an opinion? It’s just my opinion.

The board decided to move. They had been assured by management that she could raise the money to pay for the new renovation, and buy new equipment for the new (expensive) rental space, on trendy, hip, Queen West. Our new manager felt certain the grants to move and upgrade were a lock – the board bought in – and I found myself involved in another renovation. This was the third major reno of the Funnel in ten years. The first happened a decade earlier when I becam involved with the group, the second was the huge upgrade to meet the fire code and now we were building a brand new theatre on Soho Street. I was surprised that David Bennell was behind it, as he’d organized and carried out most of the first build. In my opinion, he should have known better.

The Soho renovation caught me by surprise, frankly. There was a budget, apparently, to hire some drywallers and rough in so I wasn’t needed. I do recall showing up with my tools to do some woodworking, but that’s rather vague. I’m pretty sure the budget got blown pretty quickly as there wasn’t much going on when I was there. It wasn’t long before we started to lose the necessary cash flow to finish building the new space. Even though money dried up, the rent still needed to be paid. David did show me the double walls for sound proofing the recording studio. Everything was done right in the sense it would be well built. Soundproof, sand-filled walls were as far as the new space ever got… The theatre was dead on arrival. More than ironic. There were walls and dusty floors but no risers, there was enough space for forty to eighty seats, offices, studio, and a lab space. Yet an unpleasant feeling or intuition of stalled energy pervaded the space — something was undeniably wrong. I recall asking about the missing risers, and why there weren’t any materials to work with… there was no lumber or at least not what would be needed to build. It was something of a mystery as to where anything had got to, I can only suppose the money had dried up. I never did get any answers about where the equipment went: where was the animation stand, optical printer, the editing gear? It was all very unsettling, I suppose there were answers but nothing I ever found satisfactory.

The bureaucrats won in the end. Decisively. It required sending in a mole, a fifth columnist (more irony, Fifth Column was a female punk band – a couple of them had screened work at the Funnel) hierarchal lackey to kill the Funnel dead. Just sayin’. Not that anyone conspired to make this happen, that would be paranoid. The deck is stacked and the house always wins in the end. To quote Michael Tsarion, “The real purpose of hierarchy is to eliminate the good people.” Then again, anarchy is antithetic to hierarchy. Natural enemies.

Seems like I better explain the previous paragraph. There was no mole, only the sparks and mayhem of two kinds of communities colliding. Our new manager was the one who kicked out the supports holding up a community of artists attempting to work with a completely different paradigm – a completely different world view – from that of the arts bureaucracy. It would probably help to break things down a little further. Ernest Becker is an American cultural anthropologist and writer. In his book Angel in Armor he talked about two paradigms: Power Over and Power Of. Bureaucracy would be in the “Power Over” camp, and include those who learned to armor themselves emotionally and intellectually. They can present a powerful persona that hides their true selves. Satisfaction is achieved by exerting “Power Over” others. Artists, on the other hand, in order to practice creativity, tend to shed armor (or at least pry open bigger cracks). Artists practice the powers of love, empathy, compassion and communication, their creations provide feelings of satisfaction and joy. I’m paraphrasing Becker here, yet these are general concepts that are hopefully reasonably clear — academic quibblers can go read the book. If that isn’t good enough I suggest a high speed moving coitus with a rolling donut.

The Funnel was initially (in my opinion) a group of forty artists who passionately supported the building and operation of an experimental film theater. The overall cost to rent and run the place was $400 per month so we each agreed to contribute $10. Then we built the theatre. Even though Ross provided leadership, he wasn’t the “Leader.” In practice, and I’m pretty sure this was a conscious decision on Ross’s part, when the Funnel began it was a “flat,” non-hierarchal organization. Coming out of the punk/anarchist scene, the informal consensus to be flat was already there. The whole punk ethos was fuck the corporate music/art scene, let’s get together to form a band to play for our friends at the local pub, speakeasy, basement.

When I mentioned a feeling of abandonment earlier, I was referring to losing this sense of the Funnel’s community, that’s probably at the heart of it. There wasn’t a great deal of “management” necessary amongst the forty core members when we were driven to build the theater. “Power of” made the Funnel.

As “success” began to arrive in the form of grants and notoriety, things changed. The “flat” organization of the Funnel needed to interact with government and corporate bureaucracies. Ross and Anna and a few others managed to deal with them at first, but the whole point was to screen work, not push paper. Do you see where this is going? The flat Funnel began to engage with “Power Over.” We were a community based on providing a venue for our art and other’s art. “Power Of” began to engage cultures very different from our own.

At first this took the form of conflict: there were ongoing battles with the Censor Board, and the fire code renovation was a direct result. This was probably far healthier for the Funnel community. When “success” beckoned with grants and reviews, the Funnel (in my opinion) succumbed to the notion that we needed a new form of bureaucracy, we needed “management.” Unfortunately, we weren’t fully aware of what was happening while it went down. We betrayed the integrity of our community of artists, that’s what killed us. There was a creeping disintegration of our purpose: create a venue for our community to play, to share the “Power Of.”

At any rate, in a matter of months, an organization that had been built from the ten dollars a month the members kicked in a decade earlier to pay the rent, and had become an experimental theater recognized as one of the best in the world, was now flat broke and locked out. It was a great ride while it lasted and looking back I recognize how fortunate I was to be involved. For that I’m thankful.