A series of talks by Michael Stone about chapter 3 of The Yoga Sutra a text written by mysterious author(s) often named Patanjali in the second century. Notes by MH include reveries and imaginings. Centre of Gravity Fall 2011. www.centreofgravity.org

Xmas

If you see how you spend money this month (of December – it’s a week before Christmas) you’ll know what you value.

When you’re busy the first thing that goes missing is appreciation. And the non-human world.

Museum of Silence

I’m just back from Thailand where I spent a dozen days on retreat with Richard Freeman. I arrived a couple of days early, and what I like to do in countries that don’t require helmets is to rent a scooter and go into the countryside. As soon as you leave a vehicle you are surrounded by dogs, it takes a while to get used to. I set off to visit monasteries and found one that had a massive tree, bigger than any I’d seen in Redwood Forest. I thought some monk must have sat beneath this tree, and perhaps others built a monastery around this. The next day I went back and saw a sign that announced “White Jade Buddha.” I looked into the windows and saw that there were a few monks, but no one spoke a word of English. Via body language one monk indicated that the Buddha in question was housed in a room that was opened only when a monk is ordained. Another monk said I might venture to the back of the property and find a building and open the door. I came across a white building with a door ajar. Everyone in the room was sitting, but he had urged me to go in, so I entered and found a roomful of life size Buddhas. Each one had a different face and a different jewel in their head. There were 60 stone Buddhas carved over centuries in this room in the middle of the jungle. It was a museum of silence. All those Buddhas were practicing for us. The feeling in the room is the feeling you get on retreat after everyone’s been in silence for seven days when everyone is less preoccupied with themselves. I was so moved. I went in and sat with the Buddhas and the mosquitoes and later brought Richard so we could sit together there.

It would be so beautiful if we could build something like this in North America, a building that was open a bit to the elements. That could admit the rain and the snow and the heat. Every few years we could sculpt a Buddha of someone who is sitting in this room. These statues would reside in a building that wasn’t exactly a residence or temple but a museum of silence. Because we forget so much.

I’m Here

Meditation practice connects us to gravity, to a place that is really our home. When we’re distracted or compulsive and have no time we can lose that feeling of home. We have inside us a jungle, and in the centre of that jungle there is a temple filled with Buddhas. Our job in meditation practice is to get each one of those Buddhas to settle. And the way we do this is by relaxing. In the first year of our practice, perhaps we are just trying to fight off sleep whenever we sit. But after that we pick up a little technique and it’s hard not to get tight around that. We get tight with ourselves. Eventually the mind can relax and it knows how to go home. Not our geographical or biographical home, but the home that is always with us. Or waiting for us. The enso Thich Nhat Hanh’s often draws expresses the same idea, it means: I’m here.

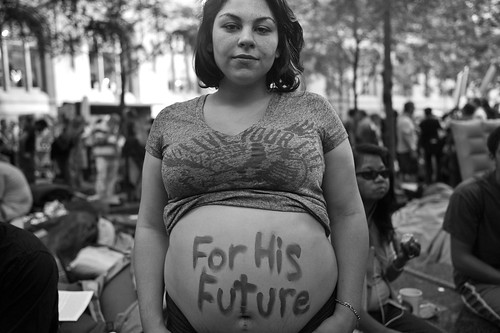

Occupy

This fall the Occupy Movement changed the conversation, the discourse of society. This shift relates to the first noble truth: to come home. From that place we know that there is suffering. We come to fully know suffering. When we sit still often the first thing we experience is fear or restlessness because there’s some part of us that’s not used to being home.

The Occupy Movement showed us that on a societal level we have forgotten about interdependence, how we are part of each other. We are 100% interdependent. We inter-are. When you sit you open up to the interdependence in your own heart.

When you’re dying, can you find generosity and not clinging? What am I holding onto right now? Who am I holding onto? Drishti, the gaze used during asana practice, is a seal of the mind. It means being able to create with the sense door of seeing a world where there is no subject and no object. How to see another person without conjuring a theoretical self who is looking at them? How to stop putting someone else outside of me?

When we start on the path and feel the joy of the path, this might be the adolescent phase. We feel good, and it’s easy to get caught. We aren’t practicing to feel good, but to be free. We come to a point where we want honesty, even if it’s painful. Where we can have the courage to look at our own lives clearly, to see clearly, and gain insight into suffering. Gaining insight into suffering is suffering. Lots of people want insight into suffering and feel good at the same time. But it’s not possible. To fully know suffering means to suffer.

Deity

How to gaze internally at what is missing with no judgment, without objectifying what you see, and what you don’t see? In Thailand there are golden Buddhas everywhere, but they’re not outside of people. One way of not objectifying is to turn them into deities. A deity is not a thing, it’s something you’re dedicated to. Whatever is showing up can be turned into a deity. Practicing mindfulness of breathing is a practice of forgiveness. At a root level we are forgiving the fact that we find ourselves not enough, inadequate, annoying. We are learning to say yes to sensation as it arises.

Patanjali invites us to experience breathing as raw sensation. It’s not something to reify, to turn into an object. It arises and passes away. The path of the yogi at the deepest level is to open to raw sensations without adding anything (like stories, for instance). That’s what the Buddhas were doing when they were sitting in that room – they weren’t comparing experiences, they were opening to experience as it is.

I asked a monk in the Thai monastery how he practiced concentration. He said when you breathe in you say “bu” and when you breathe out you say “ddha.” It’s so simple. All of these techniques allow you to see thoughts as constructions. It shows you what you’re superimposing onto experience. When you turn your experience and encounters into deities then you can relax and come home.

Label

Another technique is to label thoughts as they arise: sex, family, planning, planning in the past, sex in the past. Usually there are only five or six categories and then they get conflated with each other. When something comes up you can label it “worry” or “thoughts.” The label doesn’t have to match exactly – this isn’t a good practice for people who are deep into language because they can get hung up on the correspondences between thought and categories and unravel the whole practice.

Just This

Another technique, from the Zen tradition, is to say: “Just this.” When something comes up you can remind yourself, “Just this.”

Your life doesn’t need you to think about it all the time. Do you remember the practice we did where you have breakfast without interpreting it? To allow meaning to unfold from the other side. The door opens from the other side.

Chah

Ajahn Chah was born in 1918 in a village located in the north-eastern part of Thailand. He became a novice at a young age and received higher ordination at the age of twenty. He followed the austere Forest Tradition for years, living in forests and begging for almsfood as he wandered about on mendicant pilgrimage. He wrote a beautiful book called Being Dharma in which he wrote: “If it isn’t good let it die. If it doesn’t die, make it good.”

Holding

If something is painful let it go. How many of us have painful feelings we entertain just to torture ourselves? If there’s someone you don’t like, you torture yourself by looking at their Facebook page so you can see how badly they’re doing, or how badly you’re doing by comparison. How many moods do we entertain that harm us? Making it good, on the other hand, doesn’t mean positive thinking. It means giving space to our feelings. If there are emotions that are difficult for us, then those are the emotions we aren’t honouring and turning into deities.

How do you hold it without squeezing it?

Perhaps you hold a difficult feeling like holding a baby. With the recognition that every emotion, and every person, is a samskara, a conditioned form. You’re holding something that is always moving and changing, and there’s no reason to reify it, to turn it into an object. You hold it so lightly so that it becomes part of you. How can we look at trees and see how they let go of the leaves?

Music

Some cultural forms encourage awareness and help us become more awake. Other forms create new filters and don’t help us become awake. I used to listen to a lot of music, and this music created patterns through which I saw my life.

Asteya

In the precepts course we’ve been looking at the yama of asteya or non-stealing. Practicing without the idea of gaining. I think hidden in a lot of our meditation practices is the intention to gain something. Perhaps we’re trying to gain some letting go, some relaxation, some peace. These are just other forms of wanting, you notice them and let go of those too.

When did you first think of the past? Can you remember when you were young when you first thought about the future? What happened to make you start thinking about the past and future? There’s a moment of not being at home and then we leave this moment. Our practice is about returning home.